Deadline (video game)

| Deadline | |

|---|---|

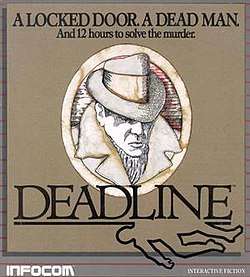

MS-DOS Cover art | |

| Developer(s) | Infocom |

| Publisher(s) | Infocom |

| Designer(s) | Marc Blank |

| Engine | ZIL |

| Platform(s) | Amstrad CPC, Apple II, Atari 8-bit, C64, MS-DOS, Osborne 1, Amiga, Atari ST |

| Release |

|

| Genre(s) | Interactive fiction |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Deadline is an interactive fiction computer game published by Infocom in 1982. Written by Marc Blank, it was one of the first murder mystery interactive fiction games. Like most Infocom titles, Deadline was created using ZIL. It is Infocom's third game.

Plot

_screenshot.jpg)

The player's character in Deadline is an unnamed police detective, summoned to a sprawling Connecticut estate to investigate the apparent suicide of wealthy industrialist Marshall Robner.[1] At first, it seems a very straightforward case: the body was discovered in the library, which had been locked from the inside, and the cause of death was an overdose of his prescribed antidepressants. But something just doesn't feel right. Could someone have killed Robner for his money? Did he make an enemy through his business dealings? Or was there some other motive? With the able assistance of level-headed Sgt. Duffy, the player has twelve hours to solve the case before it is closed forever.

The suspects, who walk around the estate pursuing their own agendas during your investigation, are:

- Leslie Robner, the victim's wife: is she the faithful, grieving widow she appears?

- George Robner, the victim's son: why doesn't he seem to be very sad about his father's death?

- Mr. McNabb, the gardener: he's very passionate about his work. Would he kill his employer?

- Mrs. Rourke, the housekeeper: is anyone in this household truly innocent?

- Mr. Baxter, Robner's business partner: is he hiding shady dealings?

- Ms. Dunbar, Robner's secretary: why does she seem so nervous?

New commands were implemented to suit the game's detective theme: the player can accuse or even arrest any of the suspects at any time. A well-timed accusation can cause an unnerved suspect to reveal previously concealed information. For an arrest to stick, however, the player must possess hard evidence of the three basics: motive, method and opportunity. Without these, the game ends with a description of why the presumed culprit was released. The standard examine and search commands are present, of course, but the player can also fingerprint objects or ask the invaluable Sgt. Duffy to analyze them.

Development

While writing Deadline, Marc Blank was strongly inspired by the 1930s out-of-print books written by Denis Wheatley. The working title of the game was "Who Killed Marshall Robner", a reference to Wheatley's Who Killed Robert Prentiss. Blank wanted the player to feel like a detective while playing the game, and designed the game and its feelies around that. Because Deadline displayed a timer rather than the movecount and score that other Infocom games of its time showed, the game needed a custom interpreter, which made porting the game to different computers more difficult.[2]

Feelies

When writing this game, Blank couldn't include all of the game's text in the limited 80KB of disk space. Working with a newly hired advertising agency, Infocom created the first feelies for this game: extra items that gave more information than could be included within the digital game itself. These materials were of very high quality and their inclusion with a computer game was unprecedented. Critics and fans hailed Infocom's pioneering move and gushed over the feelies' high quality and the immersiveness they added to the game. The feelies included:

- A police folder in a pouch containing an Inspector's Casebook[1]

- A plastic bag with 3 white pills found near Marshall Robner's body

- Notes from police interviews with Leslie and George Robner, Mr. Baxter, Ms. Dunbar, and Mrs. Rourke

- corpus delicti (summary of findings from the coroner's examination)

- A letter from Mr. Coates, Marshall Robner's lawyer, to the Chief of police

- An official memo from G.K. Anderson of the Lakeville, Connecticut police department

- A lab report on the teacup Robner drank from before his death

- A photo of the murder scene, complete with white chalk outline

(Note that in later "grey-box" editions of Deadline, many of these documents were incorporated into the Casebook, rather than existing as separate papers.)

These materials were very difficult for end-users to copy or otherwise reproduce. They included information which was essential to completing the game. So, as a side effect, the feelies acted as a deterrent to software piracy. Infocom thus started including feelies in their subsequent releases, though not every game required the use of the included feelies.

Notes

Deadline was a game of many "firsts" for Infocom: their first mystery game, their first non-Zork game, and the game that started their tradition of feelies. The number of NPCs, the independence of their behavior from the player's actions, and the parser's complexity were also considered revolutionary at the time of the game's release.

There are only two ways for the player to die,[3] but Infocom gave Deadline a difficulty rating of "Expert", largely due to the abundance of evidence and false leads to be sorted out within a short timespan.

A bug in the program made it possible to follow a certain set of instructions that resulted in Ms. Dunbar dying while another Ms. Dunbar continued to walk around the house. Upon hearing the gunshot that killed Ms. Dunbar, the alive version of Ms. Dunbar executed her AI script faithfully and ran into the room to see what had happened. This led to an amusing exchange with the game parser:

- >examine dunbar

- Which Ms. Dunbar do you mean: Ms. Dunbar, or the body of Ms. Dunbar?

Reception

Although Computer Gaming World's reviewer disliked the solution to Deadline's mystery, she praised the game's realism, documentation, extensive command vocabulary, and the frustration involved in both finding the killer and presenting enough evidence for a conviction.[4] BYTE called Deadline "fascinating" and "great fun", calling the multiple endings "a radical departure from the prototypical mystery".[5] PC Magazine called it "of the highest quality. It is thoroughly researched and tested, and it is virtually flawless".[6] The game received an award for "Best Computer Adventure" at the 4th annual Arkie Awards, where judges attributed the "richness and realism" of the game's dialogue to the advanced text parser that allows natural language input rather than the "telegraphic verb-noun phrases that other such disks generally employ".[7]:32 The New York Times Book Review also mentioned the narrative and participatory character of the game a few months later.[8] K-Power rated Deadline 8 points out of 10, stating that the game "is very exciting, is as good, or better, than Zork, and will bring long hours of enjoyment and, best of all, intrigue".[9]

In 1996, Computer Gaming World listed Deadline at #104 among their top 150 best games of all-time, calling it "a tough text adventure that placed you in the midst of an intricate police procedural and let you wander around a mansion."[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Putting Fiction on a Floppy", Time, December 1983, archived from the original on 2011-11-06

- ↑ Rouse III, Richard (2005). Game Design Theory & Practice. Second Edition. Worldware Publishing, Inc. pp. 184, 186. ISBN 1-55622-912-7.

- ↑ "Hot Gossip". Computer Games. February 1985. p. 8. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ Maloy, Deirdre (July–August 1982). "MicroReviews: Deadline" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. Vol. 2 no. 4. p. 34. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ Morgan, Chris (December 1982). "Deadline". BYTE. Vol. 7 no. 12. pp. 160–161. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ Cook, Richard (December 1982). "Deadline". PC Magazine. Vol. 1 no. 8. p. 110.

- ↑ Kunkel, Bill; Katz, Arnie (March 1983). "Arcade Alley: The Best Computer Games". Video. Vol. 6 no. 12. Reese Communications. pp. 32–33. ISSN 0147-8907.

- ↑ Rothstein, Edward, Reading and Writing: Participatory Novels, The New York Times Book Review, May 8, 1983.

- ↑ Morris, Anne (February 1984). "Deadline". K-Power. No. 1. p. 60. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ↑ Staff (November 1996). "150 Best (and 50 Worst) Games of All Time" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. No. 148. pp. 63–65, 68, 72, 74, 76, 78, 80, 84, 88, 90, 94, 98. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

External links

- Deadline at MobyGames

- Deadline overview (archived)

- Photos of all the feelies included in this game

- The Infocom Bugs List entry for Deadline