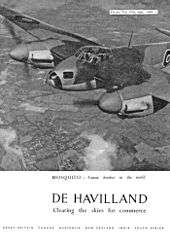

de Havilland Mosquito

| DH.98 Mosquito | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mosquito B Mk IV serial DK338 before delivery to 105 Squadron – this aircraft was used on several of 105 Squadron's low-altitude daylight bombing operations during 1943. | |

| Role | Light bomber Fighter-bomber Night fighter Maritime strike aircraft photo-reconnaissance aircraft |

| First flight | 25 November 1940[1] |

| Introduction | 15 November 1941[2] |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force Royal Canadian Air Force Royal Australian Air Force United States Army Air Forces |

| Produced | 1940–1950 |

| Number built | 7,781[3] |

The de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito is a British multi-role combat aircraft with a two-man crew. It served during and after the Second World War. It was one of few operational front-line aircraft of the era constructed almost entirely of wood and was nicknamed The Wooden Wonder.[4][nb 1] The Mosquito was also known affectionately as the "Mossie" to its crews.[5] Originally conceived as an unarmed fast bomber, the Mosquito was adapted to roles including low to medium-altitude daytime tactical bomber, high-altitude night bomber, pathfinder, day or night fighter, fighter-bomber, intruder, maritime strike aircraft, and fast photo-reconnaissance aircraft. It was also used by the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) as a fast transport to carry small high-value cargoes to, and from, neutral countries, through enemy-controlled airspace.[6] A single passenger could ride in the aircraft's bomb bay when it was adapted for the purpose.[7]

When Mosquito production began in 1941, it was one of the fastest operational aircraft in the world.[8] Entering service in autumn 1941, the first Mosquito variant was an unarmed high-speed, high-altitude photo-reconnaissance aircraft. Subsequent versions continued in this role throughout the war. From mid-1942 to mid-1943, Mosquito bombers flew high-speed, medium or low-altitude missions against factories, railways and other pinpoint targets in Germany and German-occupied Europe. From late 1943, Mosquito bombers were formed into the Light Night Strike Force and used as pathfinders for RAF Bomber Command heavy-bomber raids. They were also used as "nuisance" bombers, often dropping Blockbuster bombs – 4,000 lb (1,812 kg) "cookies" – in high-altitude, high-speed raids that German night fighters were almost powerless to intercept.

As a night fighter from mid-1942, the Mosquito intercepted Luftwaffe raids on Britain, notably those of Operation Steinbock in 1944. Starting in July 1942, Mosquito night-fighter units raided Luftwaffe airfields. As part of 100 Group, it was flown as a night fighter and as an intruder supporting Bomber Command heavy bombers that reduced losses during 1944 and 1945.[9][nb 2] As a fighter-bomber in the Second Tactical Air Force, the Mosquito took part in "special raids", such as Operation Jericho an attack on Amiens Prison in early 1944 and in precision attacks against Gestapo or German intelligence and security forces. Second Tactical Air Force Mosquitos supported the British Army during the 1944 Normandy Campaign. From 1943, Mosquitos with RAF Coastal Command attacked Kriegsmarine U-boats (particularly in 1943 in the Bay of Biscay, where significant numbers were sunk or damaged) and intercepted transport ship concentrations.

The Mosquito flew with the Royal Air Force (RAF) and other air forces in the European, Mediterranean and Italian theatres. The Mosquito was also operated by the RAF in the South East Asian theatre and by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) based in the Halmaheras and Borneo during the Pacific War. During the 1950s, the RAF replaced the Mosquito with the jet-powered English Electric Canberra.

Development

By the early-mid-1930s, de Havilland had a reputation for innovative high-speed aircraft with the DH.88 Comet racer. The later DH.91 Albatross airliner pioneered the composite wood construction that the Mosquito used. The 22-passenger Albatross could cruise at 210 miles per hour (340 km/h) at 11,000 feet (3,400 m), 100 miles per hour (160 km/h) better than the Handley Page H.P.42 and other biplanes it was replacing.[10][nb 3] The wooden monocoque construction not only saved weight and compensated for the low power of the de Havilland Gipsy Twelve engines used by this aircraft, but simplified production and reduced construction time.[11]

Air Ministry bomber requirements and concepts

On 8 September 1936, the British Air Ministry issued Specification P.13/36, which called for a twin-engine medium bomber capable of carrying a bomb load of 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg) for 3,000 miles (4,800 km) with a maximum speed of 275 miles per hour (443 km/h) at 15,000 feet (4,600 m); a maximum bomb load of 8,000 pounds (3,600 kg) that could be carried over shorter ranges was also specified.[12] Aviation firms entered heavy designs with new high-powered engines and multiple defensive turrets, leading to the production of the Avro Manchester and Handley Page Halifax.[13]

In May 1937, as a comparison to P.13/36, George Volkert, the chief designer of Handley Page, put forward the concept of a fast unarmed bomber. In 20 pages, Volkert planned an aerodynamically clean medium bomber to carry 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg) of bombs at a cruising speed of 300 miles per hour (480 km/h). There was support in the RAF and Air Ministry; Captain R N Liptrot, Research Director Aircraft 3 (RDA3), appraised Volkert's design, calculating that its top speed would exceed that of the new Supermarine Spitfire. There were, however, counter-arguments that, although such a design had merit, it would not necessarily be faster than enemy fighters for long.[14] The ministry was also considering using non-strategic materials for aircraft production, which, in 1938, had led to specification B.9/38 and the Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle medium bomber, largely constructed from spruce and plywood attached to a steel-tube frame. The idea of a small, fast bomber gained support at a much earlier stage than sometimes acknowledged though it was likely that the Air Ministry envisaged it using light alloy components.[15]

Inception of the de Havilland fast bomber

Geoffrey de Havilland also believed a bomber with an aerodynamic design, with minimal skin area, was better than the P.13/36 specification. He thought that adapting the Albatross to meet the RAF's requirements could save time. In April 1938, performance estimates were produced for a twin Rolls-Royce Merlin-powered DH.91, with the Bristol Hercules (radial engine) and Napier Sabre (H-engine) as alternatives.[12] On 7 July 1938, Geoffrey de Havilland wrote to Air Marshal Wilfrid Freeman, the Air Council's member for Research and Development, discussing the specification and arguing that in war there would be shortages of duralumin and steel but should be plenty of wood. Although inferior torsionally, the strength to weight ratio of wood was as good as duralumin or steel, and a different approach to a high-speed bomber was possible.[12]

A follow-up letter to Freeman on 27 July said that the P.13/36 specification could not be met by a twin Merlin-powered aircraft and either the top speed or load capacity would be compromised, depending on which was paramount. For example, a larger, slower, turret armed aircraft would have a range of 1,500 miles (2,400 km) carrying a 4,000-pound (1,800 kg) bomb load, with a maximum of 260 miles per hour (420 km/h) at 19,000 feet (5,800 m), and a cruising speed of 230 miles per hour (370 km/h) at 18,000 feet (5,500 m). De Havilland believed that much of a compromise, and that getting rid of surplus equipment would lead to a better design.[12] On 4 October 1938, de Havilland projected the performance of another design based on the Albatross, powered by two Merlin Xs, with a three-man crew and six or eight forward-firing guns, plus one or two manually operated guns and a tail turret. Based on a total loaded weight of 19,000 lb (8,600 kg) it would have a top speed of 300 mph (480 km/h) and cruising speed of 268 mph (431 km/h) at 22,500 ft (6,900 m).[13]

Still believing this could be improved, and after examining more concepts based on the Albatross and the new all-metal DH.95 Flamingo, de Havilland settled on designing a new aircraft that would be aerodynamically clean, wooden and powered by the Merlin, which offered substantial future development.[13] The new design would be faster than foreseeable enemy fighter aircraft, and could dispense with a defensive armament, which would slow it and make interception or losses to anti-aircraft guns more likely. Instead, high speed and good manoeuvrability would make it easier to evade fighters and ground fire.[13] The lack of turrets simplified production and reduced production time, with a delivery rate far in advance of competing designs. Without armament, the crew could be reduced to a pilot and navigator. Contemporary RAF design philosophy required well-armed heavy bombers more akin to the German schnellbomber.[16] At a meeting in early October 1938 with Geoffrey de Havilland and Charles Walker (de Havilland's chief engineer), the Air Ministry showed little interest, and instead asked de Havilland to build wings for other bombers as a sub-contractor.[17]

By September 1939 de Havilland had produced preliminary estimates for single- and twin-engined variations of light-bomber designs using different engines, speculating on the effects of defensive armament on their designs.[18] One design, completed on 6 September, was for an aircraft powered by a single 2,000 hp (1,500 kW) Napier Sabre, with a wingspan of 47-foot (14 m) and capable of carrying a 1,000-pound (450 kg) bomb load 1,500 miles (2,400 km). On 20 September, in another letter to Wilfred Freeman, de Havilland wrote "...we believe that we could produce a twin-engine bomber which would have a performance so outstanding that little defensive equipment would be needed."[18] By 4 October work had progressed to a twin-engine light bomber with a wingspan of 51 ft 3 in (15.62 m), and powered by Merlin or Griffon engines, the Merlin favoured due to availability.[18] On 7 October 1939, a month into the war, the nucleus of a design team under Eric Bishop moved to the security and secrecy of Salisbury Hall to work on what was later known as the DH.98.[19][nb 4] For more versatility, Bishop made provision for four 20 mm cannon in the forward half of the bomb bay, under the cockpit, firing via blast tubes and troughs under the fuselage.[21]

The DH.98 was too radical for the Ministry, which wanted a heavily armed, multi-role aircraft, combining medium bomber, reconnaissance and general purpose roles, as well as capable of carrying torpedoes.[17] With outbreak of war, the Ministry became more receptive, but still sceptical about an unarmed bomber. It thought the Germans would produce fighters faster than expected.[22] It suggested two forward and two rear-firing machine guns for defence.[23] The Ministry also opposed a two-man bomber, wanting at least a third crewman to reduce the work of the others on long flights.[21] The Air Council added further requirements, such as remotely controlled guns, a top speed of 275 mph (443 km/h) at 15,000 ft (4,600 m) on two-thirds engine power, and a range of 3,000 mi (4,800 km) with a 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) bomb load.[23] To appease the Ministry, de Havilland built mock-ups with a gun turret just aft of the cockpit but, apart from this compromise, de Havilland made no changes.[21]

On 12 November, at a meeting considering fast bomber ideas put forward by de Havilland, Blackburn, and Bristol, Air Marshal Freeman directed de Havilland to produce a fast aircraft, powered initially by Merlin engines, with options of using progressively more powerful engines, including the Rolls-Royce Griffon and the Napier Sabre. Although estimates were presented for a slightly larger Griffon-powered aircraft, armed with a four-gun tail turret, Freeman got the requirement for defensive weapons dropped, and a draft requirement was raised calling for a high-speed light reconnaissance bomber capable of 400 mph (640 km/h) at 18,000 ft (5,500 m).[24]

On 12 December, the Vice-Chief of the Air Staff, Director General of Research and Development, Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief (AOC-in-C) of RAF Bomber Command met to finalize the design and decide how to fit it in the RAF's aims. The AOC-in-C would not accept an unarmed bomber, but insisted on its suitability for reconnaissance missions with F8 or F24 cameras.[25] After company representatives, the Ministry and the RAF's operational commands examined a full-scale mock-up at Hatfield on 29 December 1939, the project received backing.[26] This was confirmed on 1 January 1940, when Air Marshal Freeman chaired a meeting with Geoffrey de Havilland, John Buchanan, (Deputy of Aircraft Production) and John Connolly (Buchanan's chief of staff). de Havilland claimed the DH.98 was the "fastest bomber in the world...it must be useful". Freeman supported it for RAF service, ordering a single prototype for an unarmed bomber to specification B.1/40/dh, which called for a light bomber/reconnaissance aircraft powered by two 1,280 hp (950 kW) Rolls-Royce RM3SM (an early designation for the Merlin 21) with ducted radiators, capable of carrying a 1,000-pound (450 kg) bomb load.[19][25] The aircraft was to have a speed of 397 miles per hour (639 km/h) at 23,700 feet (7,200 m) and a cruising speed of 327 miles per hour (526 km/h) at 26,600 feet (8,100 m) with a range of 1,480 miles (2,380 km) at 24,900 feet (7,600 m) on full tanks. Maximum service ceiling was to be 32,100 feet (9,800 m).[25]

On 1 March 1940, Air Marshal Roderic Hill issued a contract under Specification B.1/40, for 50 bomber-reconnaissance variants of the DH.98: this contract included the prototype, which was given the factory serial E0234.[27][28] In May 1940, specification F.21/40 was issued, calling for a long-range fighter armed with four 20 mm cannon and four .303 machine guns in the nose, after which de Havilland were authorized to build a prototype of a fighter version of the DH.98. It was decided after debate that this prototype, given the military serial number W4052, would carry Airborne Interception (AI) Mk.IV equipment as a day and night fighter.[nb 5] By June 1940, the DH.98 had been named "Mosquito".[26] Having the fighter variant kept the Mosquito project alive as there was still criticism within the government and Air Ministry of the usefulness of an unarmed bomber, even after the prototype had shown its capabilities.[26]

Project Mosquito

Once design of the DH.98 had started, de Havilland built mock-ups, the most detailed at Salisbury Hall, in the hangar where E0234 was being built. Initially, this was designed with the crew enclosed in the fuselage behind a transparent nose (similar to the Bristol Blenheim or Heinkel He 111H), but this was quickly altered to a more solid nose with a more conventional canopy.[29]

The construction of the prototype began in March 1940, but work was cancelled again after the Battle of Dunkirk, when Lord Beaverbrook, as Minister of Aircraft Production, decided there was no production capacity for aircraft like the DH.98, which was not expected to be in service until early 1942.

Lord Beaverbrook told Air Vice-Marshal Freeman that work on the project should stop, but he did not issue a specific instruction, and Freeman ignored the request.[30] In June 1940, however, Lord Beaverbrook and the Air Staff ordered that production focus on five existing types, namely the Supermarine Spitfire, Hawker Hurricane fighter, Vickers Wellington, Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley, and Bristol Blenheim bombers.[25] Work on the DH.98 prototype stopped. It seems that the project shut down when the design team were denied materials for the prototype.[31]

The Mosquito was only reinstated as a priority in July 1940, after de Havilland's General Manager L.C.L Murray, promised Lord Beaverbrook 50 Mosquitoes by December 1941, and this, only after Beaverbrook was satisfied that Mosquito production would not hinder de Havilland's primary work of producing Tiger Moth and Airspeed Oxford trainers and repairing Hurricanes as well as the licence manufacture of Merlin engines.[31] In promising Beaverbrook 50 Mosquitoes by the end of 1941, de Havilland was taking a gamble, because it was unlikely that 50 Mosquitoes could be built in such a limited time; as it transpired only 20 Mosquitoes were built in 1941, but the other 30 were delivered by mid-March 1942.[32] During the Battle of Britain, interruptions to production due to air raid warnings caused nearly a third of de Havilland's factory time to be lost.[33] Nevertheless, work on the prototype went quickly, such that E0234 was rolled out on 19 November 1940.[34]

In the aftermath of the Battle of Britain, the original order was changed to 20 bomber variants and 30 fighters. It was still uncertain whether the fighter version should have dual or single controls, or should carry a turret, so three prototypes were eventually built: W4052, W4053 and W4073. The latter, both turret armed, were later disarmed, to become the prototypes for the T.III trainer.[35] This caused some delays as half-built wing components had to be strengthened for the expected higher combat load requirements. The nose sections also had to be altered, omitting the clear perspex bomb-aimer's position, to solid noses designed to house four .303 machine guns and their ammunition.[17]

Prototypes and test flights

On 3 November 1940, the aircraft, still coded E0234, was transported by road to Hatfield, and placed in a small blast-proof assembly building, where successful engine runs were made on 19 November. Two Merlin 21 two-speed single-stage supercharged engines were installed driving three-bladed de Havilland Hydromatic constant-speed, controllable-pitch propellers.[36]

E0234 had a wingspan of 52 ft 2 in (15.90 m) and was the only Mosquito to be built with Handley Page slats on the outer leading edges of the wings. Test flights showed that these were not needed and they were disconnected and faired over with doped fabric (these slats can still be seen on W4050).[37] On 24 November 1940, taxiing trials were carried out by Geoffrey de Havilland Jr., who was the company's chief test pilot and responsible for maiden flights. The tests were successful and the prototype was subsequently readied for flight testing, making its first flight piloted by Geoffrey de Havilland, on 25 November. The flight was made 11 months after the start of detailed design work, a remarkable achievement considering the conditions of the time.[17]

For this maiden flight, E0234, weighing 14,150 pounds (6,420 kg), took off from a 450-foot (140 m) field beside the shed it was built in. John E. Walker, Chief Engine Installation designer, accompanied de Havilland. The takeoff was "straight forward and easy" and the undercarriage was not retracted until a considerable height was attained.[38] The aircraft reached 220 mph (350 km/h), with the only problem being the undercarriage doors – which were operated by bungee cords attached to the main undercarriage legs – that remained open by some 12 inches (300 mm) at that speed.[38] This problem persisted for some time. The left wing of E0234 also had a tendency to drag to port slightly, so a rigging adjustment, i.e., a slight change in the angle of the wing, was carried out before further flights.[36]

On 5 December 1940, the prototype experienced tail buffeting at speeds between 240 miles per hour (390 km/h) and 255 miles per hour (410 km/h). The pilot noticed this most in the control column, with handling becoming more difficult. During testing on 10 December, wool tufts were attached to suspect areas to investigate the direction of airflow. The conclusion was that the airflow separating from rear section of the inner engine nacelles was disturbed, leading to a localised stall and the disturbed airflow was striking the tailplane, causing buffeting. In an attempt to smooth the air flow and deflect it from forcefully striking the tailplane, non-retractable slots fitted to the inner engine nacelles and to the leading edge of the tailplane were experimented with.[40] These slots, and wing root fairings fitted to the forward fuselage and leading edge of the radiator intakes, stopped some of the vibration experienced but did not cure the tailplane buffeting.[41]

In February 1941, buffeting was eliminated by incorporating triangular fillets on the trailing edge of the wings and lengthening the nacelles, the trailing edge of which curved up to fair into the fillet some 10 in (250 mm) behind the wing's trailing edge: this meant the flaps had to be divided into inboard and outboard sections.[42][nb 6] January 1941, the prototype was carrying the military serial number W4050.[17] With the buffeting problems largely resolved, John Cunningham flew W4050 on 9 February 1941. He was greatly impressed by the "lightness of the controls and generally pleasant handling characteristics". Cunningham concluded that when the type was fitted with AI equipment, it would be a perfect replacement for the Bristol Beaufighter.[42]

During its trials on 16 January 1941, W4050 outpaced a Spitfire at 6,000 ft (1,800 m). The original estimates were that as the Mosquito prototype had twice the surface area and over twice the weight of the Spitfire Mk II, but also with twice its power, the Mosquito would end up being 20 miles per hour (32 km/h) faster. Over the next few months, W4050 surpassed this estimate, easily beating the Spitfire Mk II in testing at RAF Boscombe Down in February 1941, reaching a top speed of 392 miles per hour (631 km/h) at 22,000 feet (6,700 m) altitude, compared to a top speed of 360 miles per hour (580 km/h) at 19,500 feet (5,900 m) for the Spitfire.[1]

On 19 February, official trials began at the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) based at Boscombe Down, although de Havilland's representative was surprised by a delay in starting the tests.[43] On 24 February, as W4050 taxied across the rough airfield, the tailwheel jammed leading to the fuselage fracturing. Repairs were made by early March, using part of the fuselage of the Photo-Reconnaissance prototype W4051.[nb 7] In spite of this setback, the Initial Handling Report 767 issued by the A&AEE stated "The aeroplane is pleasant to fly ... Aileron control light and effective ..." The maximum speed reached was 388 mph (624 km/h) at 22,000 ft (6,700 m), with an estimated maximum ceiling of 33,900 ft (10,300 m) and a maximum rate of climb of 2,880 ft/min (880 m/min) at 11,400 ft (3,500 m).[43]

W4050 continued to be used for various test programs, essentially as the experimental "workhorse" for the Mosquito family.[44] In late October 1941, it returned to the factory to be fitted with Merlin 61s, the first production Merlins fitted with a two-speed, two-stage supercharger. The first flight with the new engines was on 20 June 1942.[45] W4050 recorded a maximum speed of 428 mph (689 km/h) at 28,500 ft (8,700 m) (fitted with straight-through air intakes with snowguards, engines in F.S. gear) and 437 mph (703 km/h) at 29,200 ft (8,900 m) without snowguards.[46][nb 8] In October 1942, in connection with development work on the NF Mk XV, W4050 was fitted with extended wingtips increasing the span to 59 ft 2 in (18.03 m), first flying in this configuration on 8 December.[47] Finally, fitted with high-altitude rated two-stage, two-speed Merlin 77s, it reached 439 miles per hour (707 km/h) in December 1943.[8]

Soon after these flights, W4050 was grounded and scheduled to be scrapped, but instead served as an instructional airframe at Hatfield. In September 1958, W4050 was returned to the Salisbury Hall hangar where it was built, restored to its original configuration, and became one of the primary exhibits of the de Havilland Aircraft Heritage Centre.[48][49]

W4051, which was designed from the outset to be the prototype for the photo-reconnaissance versions of the Mosquito, was slated to make its first flight in early 1941. However, the fuselage fracture in W4050 meant that W4051's fuselage was used as a replacement; W4051 was then rebuilt using a production standard fuselage and first flew on 10 June 1941. This prototype continued to use the short engine nacelles, single-piece trailing edge flaps and the 19 ft 5.5 in (5.931 m) "No. 1" tailplane used by W4050, but had production standard 54 ft 2 in (16.51 m) wings and, thus configured, became the only Mosquito prototype to fly operationally.[50]

Construction of the fighter prototype, W4052 was also carried out at the secret Salisbury Hall facility. This differed from the bomber brethren in a number of ways: it was powered by 1,460 hp (1,090 kW) Merlin 21s; had an altered canopy structure with a flat bullet-proof windscreen; a solid nose mounted four .303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns and their ammunition boxes, accessed by a single large, sideways hinged panel.;[51] four 20 mm (.79 in) Hispano Mk II cannon were housed in a compartment under the cockpit floor, with the breeches projecting into the bomb bay; and the automatic bomb bay doors were replaced by manually operated bay doors, which incorporated cartridge ejector chutes.[52]

In accordance with its role as a day/night fighter prototype W4052 was equipped with AI Mk.IV equipment, complete with an "arrowhead"-shaped transmission aerial mounted between the central Brownings, and receiving aerials through each outer wingtip, and it was painted in overall black RDM2a "Special Night" finish.[53][nb 9] It was also the first prototype constructed with the extended engine nacelles.[55] W4052 was later tested with other modifications including bomb racks, drop tanks, barrage balloon cable cutters in the leading edge of the wings, Hamilton airscrews and braking propellers, as well as drooping aileron systems that enabled steep approaches, and a larger rudder tab.

The prototype continued to serve as a test machine until it was scrapped on 28 January 1946.[8]

4055 flew the first operational Mosquito flight on 17 September 1941.[56]

During flight testing, the Mosquito prototypes were modified to test a number of experimental configurations. W4050 was fitted with a turret behind the cockpit for drag tests, after which the idea was abandoned in July 1941. W4052 had the first version of the Youngman Frill airbrake fitted to the fighter prototype. The frill was mounted around the fuselage behind the wing and was opened by bellows and venturi effect to provide rapid deceleration during interceptions and was tested between January – August 1942, but was also abandoned when it was discovered that lowering the undercarriage had the same effect with less buffeting.[56]

Production plans and American interest

The Air Ministry had authorised mass production plans to be drawn up on 21 June 1941, by which time the Mosquito had become one of the world's fastest operational aircraft.[8] The Air Ministry ordered 19 photo-reconnaissance (PR) models and 176 fighters. A further 50 were unspecified; in July 1941, the Air Ministry confirmed these would be unarmed fast bombers.[8] By the end of January 1942, contracts had been awarded for 1,378 Mosquitos of all variants, including 20 T.III trainers and 334 FB.VI bombers. Another 400 were to be built by de Havilland Canada.[57]

On 20 April 1941, W4050 was demonstrated to Lord Beaverbrook, the Minister of Aircraft Production. The Mosquito made a series of flights, including one rolling climb on one engine. Also present were US General Henry H. Arnold and his aide Major Elwood Quesada, who wrote "I ... recall the first time I saw the Mosquito as being impressed by its performance, which we were aware of. We were impressed by the appearance of the airplane that looks fast usually is fast, and the Mosquito was, by the standards of the time, an extremely well streamlined airplane, and it was highly regarded, highly respected."[42][58]

The trials set up future production plans between Britain, Australia and Canada. Six days later Arnold returned to America with a full set of manufacturer's drawings. As a result of his report five companies (Beech; Curtiss-Wright; Fairchild; Fleetwings; and Hughes) were asked to evaluate the de Havilland data. The report by Beech Aircraft summed up the general view: "It appears as though this airplane has sacrificed serviceability, structural strength, ease of construction and flying characteristics in an attempt to use construction material which is not suitable for the manufacture of efficient airplanes."[59]

The Americans did not pursue their interest, the consensus being the Lockheed P-38 Lightning could fulfil the same duties. However, Arnold felt the design was being overlooked, and urged the strategic personalities in the United States Army Air Forces to learn from the design even if they chose not to adopt it.

Several days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the USAAF then requested one airframe to evaluate on 12 December 1941, indicating the USAAF's recognition that it had entered the war without a fast dual-purpose reconnaissance aircraft.[56]

Design

Overview

The Mosquito was a fast, twin-engined aircraft with shoulder-mounted wings.[60] The most-produced variant, designated the FB Mk VI (Fighter-bomber Mark 6), was powered by two Merlin Mk 23 or Mk 25 engines driving three-bladed de Havilland hydromatic propellers. The typical fixed armament for an FB Mk VI was four Browning .303 machine guns and four 20 mm Hispano cannon while the offensive load consisted of up to 2,000 pounds (910 kg) of bombs, or eight RP-3 unguided rockets.[61]

The design was noted for light and effective control surfaces that provided good manoeuvrability but required that the rudder not be used aggressively at high speeds. Poor aileron control at low speeds when landing and taking off was also a problem for inexperienced crews.[62] For flying at low speeds, the flaps had to be set at 15°, speed reduced to 201 miles per hour (323 km/h) and rpm set to 2,650. The speed could be reduced to an acceptable 150 miles per hour (240 km/h) for low speed flying.[63] For cruising the maximum speed for obtaining maximum range was 200 miles per hour (320 km/h) at 17,000 lb (7,700 kg) weight.[63]

The Mosquito had a low stalling speed of 121 miles per hour (195 km/h) with undercarriage and flaps raised. When both were lowered, the stalling speed decreased to 100–120 miles per hour (160–190 km/h). Stall speed at normal approach angle and conditions was 100–109 miles per hour (161–175 km/h). Warning of the stall was given by buffeting and would occur 12 miles per hour (19 km/h) before stall was reached. The conditions and impact of the stall were not severe. The wing did not drop unless the control column was pulled back. The nose drooped gently and recovery was easy.[63]

Early on in the Mosquito's operational life, the cooling intake shrouds that were to cool the exhausts on production aircraft overheated after a while. Flame dampers prevented exhaust glow on night operations, but they had an effect on performance. Multiple ejector and open-ended exhaust stubs helped solve the problem and were used in the PR.VIII, B.IX and B.XVI variants. This increased speed performance in the B.IX alone by 10–13 miles (16–21 km) per hour.[8]

Fuselage

The oval-section fuselage was a frameless monocoque shell built in two halves being formed to shape by band clamps over a mahogany or concrete mould, each holding one half of the fuselage, split vertically. The shell halves were made of sheets of Ecuadorean balsawood sandwiched between sheets of Canadian birch, but in areas needing extra strength— such as along cut-outs— stronger woods replaced the balsa filler; the overall thickness of the birch and balsa sandwich skin was only 7⁄16 inch (11 mm). This sandwich skin was so stiff that no internal reinforcement was necessary from the wing's rear spar to the tail bearing bulkhead.[64] The join along the vertical centre line[65] greatly aided construction as it allowed technicians easy access to the fuselage interior.[66]

While the glue in the plywood skin dried, carpenters cut a sawtooth joint into the edges of the fuselage shells, other workers installed the controls and cabling on the inside wall. When the glue completely dried, the two halves were glued and screwed together. The fuselage was strengthened internally by seven bulkheads made up of two plywood skins separated by spruce blocks, which formed the basis on each half for the outer shell.[67] Each bulkhead was a repeat of the spruce design for the fuselage halves; a balsa sheet sandwich between two plywood sheets/skins. Bulkhead number seven carried the fittings and loads for the tailplane and rudder.

The original glue was Casein-based, later replaced by "Aerolite", a synthetic urea-formaldehyde, which was more durable.[68][nb 10] Many other types of screws and flanges (made of various woods) also held the structure together.[65] The fuselage construction joints were made from balsa wood and plywood strips with the spruce multi-ply being connected by a balsa V joint, along with the interior frame. The spruce would be reinforced by plywood strips at the point where the two halves joined to form the V-joint. Located on top of the joint the plywood formed the outer skin.[66]

During the joining of the two halves ("boxing up"), two laminated wooden clamps would be used in the after portion of the fuselage to act as support.[66][71] A covering of doped Madapolam (a fine plain woven cotton) fabric was stretched tightly over the shell and a coat of silver dope was applied, after which the exterior camouflage was applied.[72] The fuselage had a large ventral section cut-out (braced during construction) that allowed the fuselage to be lowered onto the wing centre-section. After the wing was secured lower panels were replaced and the bomb bay or armament doors fitted.[73]

Wing

The all-wood wing was built as a one-piece structure and was not divided into separate construction sections. It was made up of two main spars, spruce and plywood compression ribs, stringers, and a plywood covering. The outer plywood skin was covered and doped like the fuselage. The wing was installed into the roots by means of four large attachment points.[65] The engine radiators were fitted in the inner wing, just outboard of the fuselage on either side. These gave less drag.[65] The radiators themselves were split into three sections: an oil cooler section outboard, the middle section forming the coolant radiator and the inboard section serving the cabin heater.[74]

The wing contained metal framed and skinned ailerons, but the flaps were made of wood and were hydraulically controlled. The nacelles were mostly wood, although, for strength, the engine mounts were all metal as were the undercarriage parts.[65][75] Engine mounts of welded steel tube were added, along with simple landing gear oleos filled with rubber blocks. Wood was used to carry only in-plane loads, with metal fittings used for all triaxially loaded components such as landing gear, engine mounts, control surface mounting brackets, and the wing-to-fuselage junction.[76] The outer leading wing edge had to be brought 22 inches (56 cm) further forward to accommodate this design.[74] The main tail unit was all wood built. The control surfaces, the rudder and elevator, were aluminium framed and fabric covered.[65][75] The total weight of metal castings and forgings used in the aircraft was only 280 lb (130 kg).[77]

In November 1944, several crashes occurred in the Far East. At first, it was thought these were as a result of wing structure failures. The casein glue, it was said, cracked when exposed to extreme heat and/or monsoon conditions. This caused the upper surfaces to "lift" from the main spar. An investigating team led by Major Hereward de Havilland travelled to India and produced a report in early December 1944 stating that "the accidents were not caused by the deterioration of the glue but by shrinkage of the airframe during the wet monsoon season". However a later inquiry by Cabot & Myers definitely attributed the accidents to faulty manufacture and this was confirmed by a further investigation team by the Ministry of Aircraft Production at Defford, which found faults in six Mosquito marks (all built at de Havilland's Hatfield and Leavesden plants). The defects were similar, and none of the aircraft had been exposed to monsoon conditions or termite attack. Thus the investigators concluded that there were construction defects at the two plants.

They found that the "...standard of glueing...left much to be desired.”[78][79] Records at the time showed that accidents caused by "loss of control" were three times more frequent on Mosquitoes than on any other type of aircraft. The Air Ministry forestalled any loss of confidence in the Mosquito by holding to Major de Havilland's initial investigation in India that the accidents were caused "largely by climate"[80] To solve the problem, a sheet of plywood was set along the span of the wing to seal the entire length of the skin joint along the main spar.[78]

One benefit of the wooden construction was that it presented a relatively weak signature on contemporary radar.[81]

Systems

The fuel systems gave the Mosquito good range and endurance, using up to nine fuel tanks. Two outer wing tanks each contained 58 imperial gallons (260 L) of fuel.[82] These were complemented by two inner wing fuel tanks, each containing 143 imperial gallons (650 L), located between the wing root and engine nacelle. In the central fuselage were twin fuel tanks mounted between bulkhead number two and three aft of the cockpit.[83] In the FB.VI, these tanks contained 25 imperial gallons (110 L) each,[82] while in the B.IV and other unarmed Mosquitos each of the two centre tanks contained 68 imperial gallons (310 L).[84][85] Both the inner wing, and fuselage tanks are listed as the "main tanks" and the total internal fuel load of 452 imperial gallons (2,055 L) was initially deemed appropriate for the type.[82] In addition, the FB Mk VI could have larger fuselage tanks, increasing the capacity to 63 imperial gallons (290 L). Drop tanks of 50 imperial gallons (230 L) or 100 imperial gallons (450 l) could be mounted under each wing, increasing the total fuel load to 615 or 715 imperial gallons (2,800 or 3,250 L).[82]

The design of the Mark VI allowed for a provisional long-range fuel tank to increase range for action over enemy territory, for the installation of bomb release equipment specific to depth charges for strikes against enemy shipping, or for the simultaneous use of rocket projectiles along with a 100 imperial gallons (450 L) drop tank under each wing supplementing the main fuel cells.[86] The FB.VI had a wingspan of 54 feet 2 inches (16.51 m), a length (over guns) of 41 feet 2 inches (12.55 m). It had a maximum speed of 378 miles per hour (608 km/h) at 13,200 feet (4,000 m). Maximum take-off weight was 22,300 pounds (10,100 kg) and the range of the aircraft was 1,120 miles (1,800 km) with a service ceiling of 26,000 feet (7,900 m).[87]

To reduce fuel vaporisation at the high altitudes of photographic reconnaissance variants, the central and inner wing tanks were pressurised. The pressure venting cock located behind the pilot's seat controlled the pressure valve. As the altitude increased, the valve increased the volume applied by a pump. This system was extended to include field modifications of the fuel tank system.[88]

The engine oil tanks were in the engine nacelles. Each nacelle contained a 15 imperial gallons (68 l) oil tank, including a 2.5 imp gal (11 l) air space. The oil tanks themselves had no separate coolant controlling systems. The coolant header tank was in the forward nacelle, behind the propeller. The remaining coolant systems were controlled by the coolant radiators shutters in the forward inner wing compartment, between the nacelle and the fuselage and behind the main engine cooling radiators, which were fitted in the leading edge. Electric-pneumatic operated radiator shutters directed and controlled airflow through the ducts and into the coolant valves, to predetermined temperatures.[89]

Electrical power came from a 24 volt DC generator on the starboard (No. 2) engine and an alternator on the port engine, which supplied AC power for radios.[90] The radiator shutters, supercharger gear change, gun camera, bomb bay, bomb/rocket release and all the other crew controlled instruments were powered by a 24 volt battery.[89] The radio communication devices included VHF and HF communications, GEE navigation, and IFF and G.P. devices. The electric generators also powered the fire extinguishers. Located on the starboard side of the cockpit, the switches would operate automatically in the event of a crash. In flight, a warning light would flash to indicate a fire, should the pilot not already be aware of it. In later models, to save liquids and engine clean up time in case of belly landing, the fire extinguisher was changed to semi-automatic triggers.[91]

The main landing gear, housed in the nacelles behind the engines, were raised and lowered hydraulically. The main landing gear shock absorbers were de Havilland manufactured and used a system of rubber in compression, rather than hydraulic oleos, with twin pneumatic brakes for each wheel.[90] The Dunlop-Marstrand anti-shimmy tailwheel was also retractable.

Operational history

The de Havilland Mosquito operated in many roles during the Second World War, being tasked to perform medium bomber, reconnaissance, tactical strike, anti-submarine warfare and shipping attack and night fighter duties, both defensive and offensive, until the end of the war.[92]

In July 1941, the first production Mosquito W 4051 (a production fuselage combined with some prototype flying surfaces – see section of Article "Prototypes and test flights") was sent to No. 1 Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (PRU), operating at the time at RAF Benson.[93] Consequently, the secret reconnaissance flights of this aircraft were the first active service missions of the Mosquito. In 1944, the journal Flight[94] gave 19 September 1941 as date of the first PR mission, at an altitude "of some 20 000 ft."

On 15 November 1941, 105 Squadron, RAF, took delivery of the first operational Mosquito Mk. B.IV bomber, serial no. W4064.[95] Throughout 1942, 105 Sdn., based at RAF Horsham St. Faith, then from 29 September, RAF Marham, undertook daylight low-level and shallow dive attacks. Apart from the famous Oslo raid, these were mainly on industrial targets in occupied Netherlands, plus northern and western Germany.[96] The crews faced deadly flak and fighters, particularly Focke-Wulf Fw 190s, which they called snappers. Germany still controlled continental airspace, and the Fw 190s were often already airborne and at an advantageous altitude. It was the Mosquito’s excellent handling capabilities, rather than pure speed, that facilitated those evasions that were successful.[97] During this daylight-raiding phase, aircrew losses were high – even the losses incurred in the squadron’s dangerous Blenheim era were exceeded in percentage terms. The Roll of Honour shows 51 aircrew deaths from the end of May 1942 to April 1943.[98] In the corresponding period, crews gained three Mentions in Despatches, two DFMs and three DFCs.

The Mosquito was first announced publicly on 26 September 1942 after the Oslo Mosquito raid of 25 September. It was featured in The Times on the 28 September, and the next day the newspaper published two captioned photographs illustrating the bomb strikes and damage.[99][100]

Mosquitos were widely used by the RAF Pathfinder Force, marking targets for the main night-time strategic bombing force, as well as flying "nuisance raids" in which Mosquitos often dropped 4,000 lb "Cookies". Despite an initially high loss rate, the Mosquito ended the war with the lowest losses of any aircraft in RAF Bomber Command service. Post war, the RAF found that when finally applied to bombing, in terms of useful damage done, the Mosquito had proved 4.95 times cheaper than the Lancaster.[101] In April 1943, in response to "political humiliation" caused by the Mosquito, Hermann Göring ordered the formation of special Luftwaffe units (Jagdgeschwader 25, commanded by Oberstleutnant Herbert Ihlefeld and Jagdgeschwader 50, under Major Hermann Graf) to combat the Mosquito attacks, though these units, which were "little more than glorified squadrons", were not very successful against the elusive RAF aircraft.[102]

In one example of the daylight precision raids carried out by the Mosquito, on 30 January 1943, the 10th anniversary of the Nazis' seizure of power, a Mosquito attack knocked out the main Berlin broadcasting station while Commander in Chief Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring was speaking, putting his speech off the air.[103] Göring himself had strong views about the Mosquito, lecturing a group of German aircraft manufacturers in 1943 that:

In 1940 I could at least fly as far as Glasgow in most of my aircraft, but not now! It makes me furious when I see the Mosquito. I turn green and yellow with envy. The British, who can afford aluminium better than we can, knock together a beautiful wooden aircraft that every piano factory over there is building, and they give it a speed which they have now increased yet again. What do you make of that? There is nothing the British do not have. They have the geniuses and we have the nincompoops. After the war is over I'm going to buy a British radio set – then at least I'll own something that has always worked.[104]

The Mosquito also proved a very capable night fighter. Some of the most successful RAF pilots flew the Mosquito. Bob Braham claimed around a third of his 29 kills in a Mosquito, flying mostly daytime operations, while on night fighters Wing Commander Branse Burbridge claimed 21 kills, and Wing Commander John Cunningham claimed 19 of his 20 victories at night on Mosquitos. Mosquitos of No. 100 Group RAF were responsible for the destruction of 257 German aircraft from December 1943 to April 1945. Mosquito fighters from all units accounted for 487 German aircraft during the war, the vast majority of which were night fighters.[105]

One Mosquito is listed as belonging to German secret operations unit Kampfgeschwader 200, which tested, evaluated and sometimes clandestinely operated captured enemy aircraft during the war. The aircraft was listed on the order of battle of Versuchsverband OKL's, 2 Staffel, Stab Gruppe on 10 November and 31 December 1944. However, on both lists, the Mosquito is listed as unserviceable.[106]

The Mosquito flew its last official European war mission on 21 May 1945, when Mosquitos of 143 Squadron and 248 Squadron RAF were ordered to continue to hunt German submarines that might be tempted to continue the fight; instead of submarines all the Mosquitos encountered were passive E-boats.[107]

The last operational RAF Mosquitos were the Mosquito TT.35's, which were finally retired from No. 3 Civilian Anti-Aircraft Co-Operation Unit (CAACU) in May 1963.[108]

Variants

Until the end of 1942 the RAF always used Roman numerals (I, II, ...) for mark numbers; 1943–1948 was a transition period during which new aircraft entering service were given Arabic numerals (1, 2, ...) for mark numbers, but older aircraft retained their Roman numerals. From 1948 onwards, Arabic numerals were used exclusively.

Prototypes

Three prototypes were built, each with a different configuration. The first to fly was W4050 on 25 November 1940, followed by the fighter W4052 on 15 May 1941 and the photo-reconnaissance prototype W4051 on 10 June 1941. W4051 later flew operationally with 1 Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (1 PRU).

Photo-reconnaissance

![]() Media related to De Havilland Mosquito PR at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to De Havilland Mosquito PR at Wikimedia Commons

A total of 10 Mosquito PR Mk Is were built, four of them "long range" versions equipped with a 151 imperial gallons (690 L) overload fuel tank in the fuselage.[50] The contract called for 10 of the PR Mk I airframes to be converted to B Mk IV Series 1s.[109] All of the PR Mk Is, and the B Mk IV Series 1s, had the original short engine nacelles and short span (19 ft 5.5 in) tailplanes. Their engine cowlings incorporated the original pattern of integrated exhaust manifolds, which, after relatively brief flight time, had a troublesome habit of burning and blistering the cowling panels.[110] The first operational sortie by a Mosquito was made by a PR Mk I, W4055, on 17 September 1941; during this sortie the unarmed Mosquito PR.I evaded three Messerschmitt Bf 109s at 23,000 feet (7,000 m).[111] Powered by two Merlin 21s, the PR Mk I had a maximum speed of 382 miles per hour (615 km/h), a cruise speed of 255 miles per hour (410 km/h), a ceiling of 35,000 feet (11,000 m), a range of 2,180 nautical miles (4,040 km), and a climb rate of 2,850 feet (870 m) per minute.[112]

Over 30 Mosquito B Mk IV bombers were converted into the PR Mk IV photo-reconnaissance aircraft.[113] The first operational flight by a PR Mk IV was made by DK284 in April 1942.[114]

The Mosquito PR Mk VIII, built as a stopgap pending the introduction of the refined PR Mk IX, was the next photo-reconnaissance version. The five VIIIs were converted from B Mk IVs and became the first operational Mosquito version to be powered by two-stage, two-speed supercharged engines, using 1,565 hp (1,167 kW) Rolls-Royce Merlin 61 engines in place of Merlin 21/22s. The first PR Mk VIII, DK324 first flew on 20 October 1942.[115] The PR Mk VIII had a maximum speed of 436 mph (702 km/h), an economical cruise speed of 295 mph (475 km/h) at 20,000 ft, and 350 mph (560 km/h) at 30,000 ft,[116] a ceiling of 38,000 ft (12,000 m), a range of 2,550 nmi (4,720 km), and a climb rate of 2,500 ft per minute (760 m).[112]

The Mosquito PR Mk IX, 90 of which were built, was the first Mosquito variant with two-stage, two-speed engines to be produced in quantity; the first of these, LR405, first flew in April 1943.[115] The PR Mk IX was based on the Mosquito B Mk IX bomber and was powered by two 1,680 hp (1,250 kW) Merlin 72/73 or 76/77 engines. It could carry either two 50 imperial gallons (230 L), two 100 imperial gallons (450 L) or two 200 imperial gallons (910 L) droppable fuel tanks.[114]

The Mosquito PR Mk XVI had a pressurised cockpit and, like the Mk IX, was powered by two Rolls-Royce Merlin 72/73 or 76/77 piston engines. This version was equipped with three overload fuel tanks, totalling 760 imperial gallons (3,500 L) in the bomb bay, and could also carry two 50 imperial gallons (230 L) or 100 imperial gallons (450 L) drop tanks.[117] A total of 435 of the PR Mk XVI were built.[114] The PR Mk XVI had a maximum speed of 415 mph (668 km/h), a cruise speed of 250 mph (400 km/h), ceiling of 38,500 ft (11,700 m), a range of 2,450 nmi (4,540 km), and a climb rate of 2,900 feet per minute (884 m).[112]

The Mosquito PR Mk 32 was a long-range, high-altitude, pressurised photo-reconnaissance version. It was powered by a pair of two-stage supercharged 1,960 hp (1,460 kW) Rolls-Royce Merlin 113 and Merlin 114 piston engines, the Merlin 113 on the starboard side and the Merlin 114 on the port. First flown in August 1944, only five were built and all were conversions from PR.XVIs.[118]

The Mosquito PR Mk 34 and PR Mk 34A was a very long-range unarmed high altitude photo-reconnaissance version. The fuel tank and cockpit protection armour were removed. Additional fuel was carried in a bulged bomb bay: 1,192 gallons—the equivalent of 5,419 miles (8,721 km). A further two 200-gallon (910-litre) drop tanks under the outer wings gave a range of 3,600 miles (5,800 km) cruising at 300 mph (480 km/h). Powered by two 1,690 hp (1,260 kW) Merlin 114s first used in the PR.32. The port Merlin 114 drove a Marshal cabin supercharger. A total of 181 were built, including 50 built by Percival Aircraft Company at Luton.[118] The PR.34's maximum speed (TAS) was 335 mph (539 km/h) at sea level, 405 mph (652 km/h) at 17,000 ft (5,200 m) and 425 mph (684 km/h) at 30,000 ft (9,100 m).[119] All PR.34s were installed with four split F52 vertical cameras, two forward, two aft of the fuselage tank and one F24 oblique camera. Sometimes a K-17 camera was used for air surveys. In August 1945, the PR.34A was the final photo-reconnaissance variant with one Merlin 113A and 114A each delivering 1,710 hp (1,280 kW).[120]

Colonel Roy M. Stanley II, USAF (RET) wrote: "I consider the Mosquito the best photo-reconnaissance aircraft of the war".[121]

After the end of World War II Spartan Air Services used ten ex-RAF Mosquitoes, mostly B.35's plus one of only six PR.35's built, for high-altitude photographic survey work in Canada.[122]

Bombers

![]() Media related to De Havilland Mosquito B at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to De Havilland Mosquito B at Wikimedia Commons

On 21 June 1941 the Air Ministry ordered that the last 10 Mosquitoes, ordered as photo-reconnaissance aircraft, should be converted to bombers. These 10 aircraft were part of the original 1 March 1940 production order and became the B Mk IV Series 1. W4052 was to be the prototype and flew for the first time on 8 September 1941.[124]

The bomber prototype led to the B Mk IV, of which 273 were built: apart from the 10 Series 1s, all of the rest were built as Series 2s with extended nacelles, revised exhaust manifolds, with integrated flame dampers, and larger tailplanes.[125] Series 2 bombers also differed from the Series 1 in having a larger bomb bay to increase the payload to four 500 lb (230 kg) bombs, instead of the four 250 pounds (110 kg) bombs of Series 1. This was made possible by shortening the tail of the 500 pounds (230 kg) bomb so that these four larger weapons could be carried (or a 2,000 lb (920;kg) total load).[125] The B Mk IV entered service in May 1942 with 105 Squadron.

In April 1943 it was decided to convert a B Mk IV to carry a 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) Blockbuster bomb (nicknamed a Cookie). The conversion, including modified bomb bay suspension arrangements, bulged bomb bay doors and fairings, was relatively straightforward and 54 B.IVs were modified and distributed to squadrons of the Light Night Striking Force.[125][126] 27 B Mk IVs were later converted for special operations with the Highball anti-shipping weapon, and were used by 618 Squadron, formed in April 1943 specifically to use this weapon.[127] A B Mk IV, DK290 was initially used as a trials aircraft for the bomb, followed by DZ471,530 and 533.[128] The B Mk IV had a maximum speed of 380 mph (610 km/h), a cruising speed of 265 mph (426 km/h), ceiling of 34,000 ft (10,000 m), a range of 2,040 nmi (3,780 km), and a climb rate of 2,500 ft per minute (762 m).[112]

Other bomber variants of the Mosquito included the Merlin 21 powered B Mk V high-altitude version. Trials with this configuration were made with W4057, which had strengthened wings and two additional fuel tanks, or alternatively, two 500 pounds (230 kg) bombs. This design was not produced in Britain, but formed the basic design of the Canadian-built B.VII. Only W4057 was built in prototype form.[129] The Merlin 31 powered B Mk VII was built by de Havilland Canada and first flown on 24 September 1942. It only saw service in Canada, 25 were built. Six were handed over to the United States Army Air Forces.

B Mk IX (54 built) was powered by the Merlin 72,73, 76 or 77. The two-stage Merlin variant was based on the PR.IX. The prototype DK 324 was converted from a PR.VIII and first flew on 24 March 1943.[130] In October 1943 it was decided that all B Mk IVs and all B Mk IXs then in service would be converted to carry the 4,000 pounds (1,800 kg) "Cookie", and all B Mk IXs built after that date were designed to allow them to be converted to carry the weapon.[131] The B Mk IX had a maximum speed of 408 mph (657 km/h), an economical cruise speed of 295 mph (475 km/h) at 20,000 ft, and 350 mph (560 km/h) at 30,000 ft,[116] ceiling of 36,000 ft (11,000 m), a range of 2,450 nmi (4,540 km), and a climb rate of 2,850 feet per minute (869 m). The IX could carry a maximum load of 2,000–4,000 lb (910–1,810 kg) of bombs.[112] A Mosquito B Mk IX holds the record for the most combat operations flown by an Allied bomber in the Second World War. LR503, known as "F for Freddie" (from its squadron code letters, GB*F), first served with No. 109 and subsequently, No. 105 RAF squadrons. It flew 213 sorties during the war, only to crash at Calgary airport during the Eighth Victory Loan Bond Drive on 10 May 1945, two days after Victory in Europe Day, killing both the pilot, Flt. Lt. Maurice Briggs, DSO, DFC, DFM and navigator Fl. Off. John Baker, DFC and Bar.[132]

The B Mk XVI was powered by the same variations as the B.IX. All B Mk XVIs were capable of being converted to carry the 4,000 pounds (1,800 kg) "Cookie".[131] The two-stage powerplants were added along with a pressurised cabin. DZ540 first flew on 1 January 1944. The prototype was converted from a IV (402 built). The next variant, the B Mk XX, was powered by Packard Merlins 31 and 33s. It was the Canadian version of the IV. Altogether, 245 were built. The B Mk XVI had a maximum speed of 408 mph (657 km/h), an economical cruise speed of 295 mph (475 km/h) at 20,000 ft, and 350 mph (560 km/h) at 30,000 ft,[116] ceiling of 37,000 ft (11,000 m), a range of 1,485 nmi (2,750 km), and a climb rate of 2,800 ft per minute (853 m). The type could carry 4,000 pounds (1,800 kg) of bombs.[112]

The B.35 was powered by Merlin 113 and 114As. Some were converted to TT.35s (Target Tugs) and others were used as PR.35s (photo-reconnaissance).[130] The B.35 had a maximum speed of 422 mph (679 km/h), a cruising speed of 276 mph (444 km/h), ceiling of 42,000 ft (13,000 m), a range of 1,750 nmi (3,240 km), and a climb rate of 2,700 ft per minute (823 m).[133] A total of 174 B.35s were delivered up to the end of 1945. [nb 11] A further 100 were delivered from 1946 for a grand total of 274, 65 of which were built by Airspeed Ltd.[nb 12][120]

Fighters

![]() Media related to De Havilland Mosquito F at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to De Havilland Mosquito F at Wikimedia Commons

Developed during 1940, the first prototype of the Mosquito F Mk II was completed on 15 May 1941. These Mosquitos were fitted with four 20 mm (0.79 in) Hispano cannon in the fuselage belly and four .303 (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns mounted in the nose. On production Mk IIs the machine guns and ammunition tanks were accessed via two centrally hinged, sideways opening doors in the upper nose section. To arm and service the cannon the bomb bay doors were replaced by manually operated bay doors: the F and NF Mk IIs could not carry bombs.[52] The type was also fitted with a gun camera in a compartment above the machine guns in the nose and was fitted with exhaust flame dampers to reduce the glare from the Merlin XXs.[136]

In the summer of 1942, during clear weather, Britain experienced day-time incursions of the high-altitude reconnaissance bomber, the pressurised Junkers Ju-86P [137]. In some instances bombs were dropped on industrially sensitive cities including Luton, close to the main De Havilland offices and factory. As a result of these raids, starting in September 1942, five Mosquito B Mk IV bombers were quickly converted into F Mk XV high-altitude, pressurised fighters, powered by two-stage Merlin 73s and 77s fitted with four-bladed propellers.[138]

The first of these conversions was MP469, which was wheeled into the experimental shop on 7 September and first flew on 14 September. The bomber nose forward of the cockpit was cut off and a standard fighter nose, complete with four .303 Brownings, grafted on in its place. The pressurised crew cabin retained the bomber's canopy structure, also retaining its vee-shaped, two-piece windscreen, while the bomber's control wheel was replaced by the fighter's control stick. Extended, pointed, wingtips increased the wingspan to 59 ft (18 m). The airframe was lightened by removing all armour plating, bullet-proofing from the fuel and oil tanks, and the outer wing and fuselage tanks (leaving the inner wing tanks with a total capacity of 287 imp gal (1,300 L)). Other ancillary equipment was also removed, and smaller-diameter main wheels were fitted after the first few flights. At a loaded weight of 16,200 lb (7,300 kg) the Mk XV was 2,300 lb (1,000 kg) lighter than a standard Mk II, and reached an altitude of 45,000 feet (14,000 m). Four more B Mk IVs were converted into F Mk XVs, and, in late 1942, were further modified to become NF MK XVs.[139]

All Mosquito fighters and fighter bombers, apart from the F Mk XV, featured a modified canopy structure incorporating a flat, single piece armoured windscreen, and the crew entry/exit door was moved from the bottom of the forward fuselage to the right side of the nose, just forward of the wing leading edge.[140]

Night fighters

![]() Media related to De Havilland Mosquito NF at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to De Havilland Mosquito NF at Wikimedia Commons

At the end of 1940, the Air Staff's preferred turret-equipped night fighter design to Operational Requirement O.R 95 was the Gloster F.18/40 (derived from their F.9/37). However, although in agreement as to the quality of the Gloster company's design, the Ministry of Aircraft Production was concerned that Gloster would not be able to work on the F.18/40 and also the jet fighter design, considered the greater priority. Consequently, in mid-1941 the Air Staff and MAP agreed that the Gloster aircraft would be dropped and the Mosquito, when fitted with a turret would be considered for the night fighter requirement.[141]

The first production night fighter Mosquitos - minus turrets - were designated NF Mk II. A total of 466 were built with the first entering service with No. 157 Squadron in January 1942, replacing the Douglas Havoc. These aircraft were similar to the F Mk II, but were fitted with the AI Mk IV metric wavelength radar. The herring-bone transmitting antenna was mounted on the nose and the dipole receiving antennae were carried under the outer wings.[142] A number of NF IIs had their radar equipment removed and additional fuel tanks installed in the bay behind the cannon for use as night intruders. These aircraft, designated NF II (Special) were first used by 23 Squadron in operations over Europe in 1942.[143] 23 Squadron was then deployed to Malta on 20 December 1942, and operated against targets in Italy.[144]

Ninety-seven NF Mk IIs were upgraded with 3.3 GHz frequency, low-SHF-band AI Mk VIII radar and these were designated NF Mk XII. The NF Mk XIII, of which 270 were built, was the production equivalent of the Mk XII conversions. These "centimetric" radar sets were mounted in a solid "thimble" (Mk XII / XIII) or universal "bull nose" (Mk XVII / XIX) radome, which required the machine guns to be dispensed with.

Four F Mk XVs were converted to the NF Mk XV. These were fitted with AI Mk VIII in a "thimble" radome, and the .303 Brownings were moved into a gun pack fitted under the forward fuselage.[145]

NF Mk XVII was the designation for 99 NF Mk II conversions, with single-stage Merlin 21, 22, or 23 engines, but British AI.X (US SCR-720) radar.

The NF Mk XIX was an improved version of the NF XIII. It could be fitted with American or British AI radars; 220 were built.

The NF Mk 30 was the final wartime variant and was a high-altitude version, powered by two 1,710 hp (1,280 kW) Rolls-Royce Merlin 76s. The NF Mk 30 had a maximum speed of 424 mph (682 km/h) at 26,500 ft (8,100 m).[146] It also carried early electronic countermeasures equipment. 526 were built.

Other Mosquito night fighter variants planned but never built included the NF Mk X and NF Mk XIV (the latter based on the NF Mk XIII), both of which were to have two-stage Merlins. The NF Mk 31 was a variant of the NF Mk 30, but powered by Packard Merlins.[147]

Mosquito night intruders of 100 Group, Bomber Command, were also fitted with a device called "Serrate" to allow them to track down German night fighters from their Lichtenstein B/C (low-UHF-band) and Lichtenstein SN-2 (lower end of the VHF FM broadcast band) radar emissions, as well as a device named "Perfectos" that tracked German IFF signals.

After the war, two more night fighter versions were developed: The NF Mk 36 was similar to the Mosquito NF Mk 30, but fitted with the American-built AI.Mk X radar. Powered by two 1,690 hp (1,260 kW) Rolls-Royce Merlin 113/114 piston engines; 266 built. Max level speeds (TAS) with flame dampers fitted were 305 mph (491 km/h) at sea level, 380 mph (610 km/h) at 17,000 ft (5,200 m), and 405 mph (652 km/h) at 30,000 ft (9,100 m).[119]

The NF Mk 38, 101 of which were built, was also similar to the Mosquito NF Mk 30, but fitted with the British-built AI Mk IX radar. This variant suffered from stability problems and did not enter RAF service: 60 were eventually sold to Yugoslavia.[148] According to the Pilot's Notes and Air Ministry 'Special Flying Instruction TF/487', which posted limits on the Mosquito's maximum speeds, the NF Mk 38 had a VNE of 370 knots (425 mph), without under-wing stores, and within the altitude range of sea level to 10,000 ft (3,000 m). However, from 10,000 to 15,000 ft (4,600 m) the maximum speed was 348 knots (400 mph). As the height increased other recorded speeds were; 15,000 to 20,000 ft (6,100 m) 320 knots (368 mph); 20,000 to 25,000 ft (7,600 m), 295 knots (339 mph); 25,000 to 30,000 ft (9,100 m), 260 knots (299 mph); 30,000 to 35,000 ft (11,000 m), 235 knots (270 mph). With two added 100-gallon fuel tanks this performance fell; between sea level and 15,000 feet 330 knots (379 mph); between 15,000 and 20,000 ft (6,100 m) 320 knots (368 mph); 20,000 to 25,000 ft (7,600 m), 295 knots (339 mph); 25,000 to 30,000 ft (9,100 m), 260 knots (299 mph); 30,000 to 35,000 ft (11,000 m), 235 knots (270 mph). Little difference was noted above 15,000 ft (4,600 m).[149]

Fighter-bombers

![]() Media related to De Havilland Mosquito FB at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to De Havilland Mosquito FB at Wikimedia Commons

The FB Mk VI, which first flew on 1 June 1942, was powered by two 1,460 hp (1,090 kW) Merlin 21s or 1,635 hp (1,219 kW) Merlin 25s, and introduced a re-stressed and reinforced "basic" wing structure capable of carrying single 250-pound (110 kg) or 500-pound (230 kg) bombs on racks housed in streamlined fairings under each wing, or up to eight RP-3 25lb or 60 lb rockets. In addition fuel lines were added to the wings to enable single 50 imp gal (230 l) or 100 imp gal (450 l) drop tanks to be carried under each wing.[114][150] The usual fixed armament was four 20 mm Hispano Mk.II cannon and four .303 (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns, while two 250-pound (110 kg) or 500-pound (230 kg) bombs could be carried in the bomb bay.[nb 13]

Unlike the F Mk II, the ventral bay doors were split into two pairs, with the forward pair being used to access the cannon, while the rear pair acted as bomb bay doors.[151] The maximum fuel load was 719.5 imperial gallons (3,271 l) distributed between 453 imperial gallons (2,060 l) internal fuel tanks, plus two overload tanks, each of 66.5 imperial gallons (302 l) capacity, which could be fitted in the bomb bay, and two 100 imperial gallons (450 l) drop tanks.[150] All-out level speed is often given as 368 mph (592 km/h), although this speed applies to aircraft fitted with saxophone exhausts. The test aircraft (HJ679) fitted with stub exhausts was found to be performing below expectations. It was returned to de Havilland at Hatfield where it was serviced. Its top speed was then tested and found to be 384 mph (618 km/h), in line with expectations.[152] 2,298 FB Mk VIs were built, nearly one-third of Mosquito production.[114] Two were converted to TR.33 carrier-borne, maritime strike prototypes.[114]

The FB Mk VI proved capable of holding its own with single-engine fighter aircraft in addition to bombing. For example, on 15 January 1945 Mosquito FB Mk VIs of 143 Squadron were engaged by 30 Focke-Wulf Fw 190s from Jagdgeschwader 5: nonetheless, the Mosquitos sank an armed trawler and two merchant ships, losing five Mosquitos (two to flak)[153] but shooting down five Fw 190s.[154]

Another fighter-bomber variant was the Mosquito FB Mk XVIII (sometimes known as the Tsetse) of which one was converted from a FB Mk VI to serve as prototype and 17 were purpose-built. The Mk XVIII was armed with a Molins "6-pounder Class M" cannon: this was a modified QF 6-pounder (57 mm) anti-tank gun fitted with an auto-loader to allow both semi- or fully automatic fire.[nb 14] 25 rounds were carried, with the entire installation weighing 1,580 lb (720 kg).[118] In addition, 900 lb (410 kg) of armour was added within the engine cowlings, around the nose and under the cockpit floor to protect the engines and crew from heavily armed U-boats, the intended primary target of the Mk XVIII.[155] Two or four .303 (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns were retained in the nose and were used to "sight" the main weapon onto the target.[118]

The Air Ministry initially suspected that this variant would not work, but tests proved otherwise. Although the gun provided the Mosquito with yet more anti-shipping firepower for use against U-boats, it required a steady approach run to aim and fire the gun, making it vulnerable to anti-aircraft fire. The gun had a muzzle velocity of 2,950 ft/s (900 m/s)[118] and an excellent range of some 1,800 – 1,500 yards (1,650 – 1,370 m). It was sensitive to sidewards movement; an attack required a dive from 5,000 ft (1,500 m) at a 30° angle with the turn and bank indicator on centre. A move during the dive could jam the gun.[156] The prototype HJ732 was converted from a FB.VI and was first flown on 8 June 1943.[118]

The effect of the new weapon was demonstrated on 10 March 1944 when Mk XVIIIs from 248 Squadron (escorted by four Mk VIs) engaged a German convoy of one U-boat and four destroyers, protected by 10 Ju 88s. Three of the Ju 88s were shot down. Pilot Tony Phillips destroyed one Ju 88 with four shells, one of which tore an engine off the Ju 88. The U-boat was damaged. On 25 March, U-976 was sunk by Molins-equipped Mosquitos.[157] On 10 June, U-821 was abandoned in the face of intense air attack from No. 248 Squadron, and was later sunk by a Liberator of No. 206 Squadron.[158] On 5 April 1945 Mosquitos with Molins attacked five German surface ships in the Kattegat and again demonstrated their value by setting them all on fire and sinking them.[159][160] A German Sperrbrecher ("minefield breaker") was lost with all hands, with some 200 bodies being recovered by Swedish vessels.[159] Some 900 German soldiers died in total.[159] On 9 April, German U-boats U-804, U-843 and U-1065 were spotted in formation heading for Norway. All were sunk.[159][161] U-251 and U-2359 followed on 19 April and 2 May 1945.[162]

Despite the preference for rockets, a further development of the large gun idea was carried out using the even larger, 96 mm calibre QF 32-pounder, a gun based on the QF 3.7 inch AA gun designed for tank use, the airborne version using a novel form of muzzle brake. Developed to prove the feasibility of using such a large weapon in the Mosquito, this installation was not completed until after the war, when it was flown and fired in a single aircraft without problems, then scrapped.

Designs based on the Mk VI were the FB Mk 26, built in Canada, and the FB Mk 40, built in Australia, powered by Packard Merlins. The FB.26 improved from the FB.21 using 1,620 hp (1,210 kW) single stage Packard Merlin 225s. Some 300 were built and another 37 converted to T.29 standard.[118] 212 FB.40s were built by de Havilland Australia. Six were converted to PR.40; 28 to PR.41s, one to FB.42 and 22 to T.43 trainers. Most were powered by Packard-built Merlin 31 or 33s.[120]

Trainers

The Mosquito was also built as the Mosquito T Mk III two-seat trainer. This version, powered by two Rolls-Royce Merlin 21s, was unarmed and had a modified cockpit fitted with dual control arrangements. A total of 348 of the T Mk III were built for the RAF and Fleet Air Arm. de Havilland Australia built 11 T Mk 43 trainers, similar to the Mk III.

Torpedo-bombers

To meet specification N.15/44 for a navalised Mosquito for Royal Navy use as a torpedo bomber, de Havilland produced a carrier-borne variant. A Mosquito FB.VI was modified as a prototype designated Sea Mosquito TR Mk 33 with folding wings, arrester hook, thimble nose radome, Merlin 25 engines with four-bladed propellers and a new oleo-pneumatic landing gear rather than the standard rubber-in-compression gear. Initial carrier tests of the Sea Mosquito were carried out by Eric "Winkle" Brown aboard HMS Indefatigable, the first landing-on taking place on 25 March 1944. An order for 100 TR.33s was placed although only 50 were built at Leavesden. Armament was four 20 mm cannon, two 500 lb bombs in the bomb bay (another two could be fitted under the wings), eight 60 lb rockets (four under each wing) and a standard torpedo under the fuselage. The first production TR.33 flew on 10 November 1945. This series was followed by six Sea Mosquito TR Mk 37s, which differed in having ASV Mk XIII radar instead of the TR.33's AN/APS-6.

Target tugs

The RAF's target tug version was the Mosquito TT Mk 35, which were the last aircraft to remain in operational service with No 3 CAACU at Exeter, being finally retired in 1963. These aircraft were then featured in the film 633 Squadron. A number of B Mk XVIs bombers were converted into TT Mk 39 target tug aircraft. The Royal Navy also operated the Mosquito TT Mk 39 for target towing. Two ex-RAF FB.6s were converted to TT.6 standard at Manchester (Ringway) Airport by Fairey Aviation in 1953–1954, and delivered to the Belgian Air Force for use as towing aircraft from the Sylt firing ranges.

Canadian-built

A total of 1,133[164] (to 1945) Mosquitos were built by De Havilland Canada at Downsview Airfield in Downsview Ontario (now Downsview Park in Toronto Ontario).

- Mosquito B Mk VII : Canadian version based on the Mosquito B Mk V bomber aircraft. Powered by two 1,418 hp (1,057 kW) Packard Merlin 31 piston engines; 25 built.

- Mosquito B Mk XX : Canadian version of the Mosquito B Mk IV bomber aircraft; 145 built, of which 40 were converted into F-8 photo-reconnaissance aircraft for the USAAF.

- Mosquito FB Mk 21 : Canadian version of the Mosquito FB Mk VI fighter-bomber aircraft. Powered by two 1,460 hp (1,090 kW) Rolls-Royce Merlin 31 piston engines, three built.

- Mosquito T Mk 22 : Canadian version of the Mosquito T Mk III training aircraft.

- Mosquito B Mk 23 : Unused designation for a bomber variant.

- Mosquito FB Mk 24 : Canadian fighter-bomber version. Powered by two 1,620 hp (1,210 kW) Rolls-Royce Merlin 301 piston engines; two built.

- Mosquito B Mk 25 : Improved version of the Mosquito B Mk XX Bomber aircraft. Powered by two 1,620 hp (1,210 kW) Packard Merlin 225 piston engines; 400 built.

- Mosquito FB Mk 26 : Improved version of the Mosquito FB Mk 21 fighter-bomber aircraft. Powered by two 1,620 hp (1,210 kW) Packard Merlin 225 piston engines; 338 built.

- Mosquito T Mk 27 : Canadian-built training aircraft.

- Mosquito T Mk 29 : A number of FB Mk 26 fighters were converted into T Mk 29 trainers.

Australian-built

.jpg)

- Mosquito FB Mk 40 : Two-seat fighter-bomber version for the RAAF. Powered by two 1,460 hp (1,089 kW) Roll-Royce Merlin 31 piston engines. A total of 178 built in Australia.

- Mosquito PR Mk 40 : This designation was given to six FB Mk 40s, which were converted into photo-reconnaissance aircraft.

- Mosquito FB Mk 41 : Two-seat fighter-bomber version for the RAAF. A total of 11 were built in Australia.

- Mosquito PR Mk 41 : Two-seat photo-survey version for the RAAF. A total of 17 were built in Australia.

- Mosquito FB Mk 42 : Two-seat fighter-bomber version. Powered by two Rolls-Royce Merlin 69 piston engines. One FB Mk 40 aircraft was converted into a Mosquito FB Mk 42.

- Mosquito T Mk 43 : Two-seat training version for the RAAF. A total of 11 FB Mk 40s were converted into Mosquito T Mk 43s.

Highball

A number of Mosquito IVs were modified by Vickers-Armstrongs to carry Highball "bouncing bombs" and were allocated Vickers Type numbers:

- Type 463 – Prototype Highball conversion of Mosquito IV DZ741.

- Type 465 – Conversion of 33 Mosquito IVs to carry Highball.

Production

Details

In England, fuselage shells were mainly made by furniture companies, including Ronson, E. Gomme, Parker Knoll, Austinsuite and Styles & Mealing. Some of the specialised wood veneer used in the construction of the Mosquito was made by Roddis Manufacturing in Marshfield, Wisconsin in the United States and Canadian Veneers in Pembrooke, Ontario, Canada. Hamilton Roddis had teams of young women ironing the (unusually thin) strong wood veneer before shipping to the UK.[165][166][167] Wing spars were made by J. B. Heath and Dancer & Hearne. Many of the other parts, including flaps, flap shrouds, fins, leading edge assemblies and bomb doors were also produced in High Wycombe, which was well suited to these tasks because it had a well-established furniture manufacturing industry. Dancer & Hearne processed much of the wood from start to finish, receiving timber and transforming it into finished wing spars at their High Wycombe factory.

About 5,000 of the 7,781 Mosquitos made contained parts made in High Wycombe.[165] In Canada, fuselages were built in the Oshawa, Ontario plant of General Motors of Canada Limited. These were shipped to De Havilland Canada in Toronto for mating to the wings and completion. As a secondary manufacturer, de Havilland Australia started construction in Sydney. These production lines added 1,133[168] from Canada and 212 from Australia.

Total Mosquito production was 7,781, of which 6,710 were built during the war. The ferrying of Mosquitos from Canada to the war front was problematic, as a small fraction of the aircraft mysteriously disappeared over mid-Atlantic. The theory of "auto-explosion" was offered, and, although a considerable effort by de Havilland Canada to resolve production problems with engine and oil systems reduced the number of aircraft lost, the actual cause of the losses was never established. The company introduced an additional five hours flight testing to clear production aircraft before the ferry flight. By the end of the war nearly 500 Mosquito bombers and fighter-bombers had been delivered successfully by the Canadian operation.[169]