Blue

| Blue | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Spectral coordinates | |||||||||

| Wavelength | 450–495 nm | ||||||||

| Frequency | ~670–610 THz | ||||||||

| Hex triplet | #0000FF | ||||||||

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (0, 0, 255) | ||||||||

| HSV (h, s, v) | (240°, 100%, 100%) | ||||||||

| Source | HTML/CSS[1] | ||||||||

|

B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) | |||||||||

Blue is the colour between violet and green on the spectrum of visible light. Human eyes perceive blue when observing light with a wavelength between 450 and 495 nanometres. Blues with a higher frequency and thus a shorter wavelength appear more violet, while those with a lower frequency and a longer wavelength gradually appear more green. Pure blue, in the middle, has a wavelength of 470 nanometres. In painting and traditional colour theory, blue is one of the three primary colours of pigments, along with red and yellow, which can be mixed to form a wide gamut of colours. Red and blue mixed together form violet, blue and yellow together form green. Blue is also a primary colour in the RGB colour model, used to create all the colours on the screen of a television or computer monitor.

The modern English word blue comes from Middle English bleu or blewe, from the Old French bleu, a word of Germanic origin related to Old Dutch, Old High German,[2] Old Saxon blāo and Old Frisian blāw, blau.[3][4] The clear sky and the deep sea appear blue because of an optical effect known as Rayleigh scattering. When sunlight passes through the atmosphere, the blue wavelengths are scattered more widely by the oxygen and nitrogen molecules, and more blue comes to our eyes. An optical effect called Tyndall scattering, similar to Rayleigh scattering, explains blue eyes; there is no blue pigment in blue eyes. Distant objects appear more blue because of another optical effect called atmospheric perspective.

Blue has been used for art and decoration since ancient times. The semi-precious stone lapis lazuli, coming from mines in Afghanistan, was used in ancient Egypt for jewelry and ornament and later, in The Renaissance, to make the pigment ultramarine, the most expensive of all pigments. It is the most important color in Judaism. In the Middle Ages, cobalt blue was used to colour the stained glass windows of cathedrals. Beginning in the 9th century, Chinese artists used cobalt to make fine blue and white porcelain. Blue dyes for clothing were made from woad in Europe and indigo in Asia and Africa. In 1828 a synthetic ultramarine pigment was developed, and synthetic blue dyes and pigments gradually replaced mineral pigments and vegetable dyes. Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Vincent van Gogh and other late 19th century painters used ultramarine and cobalt blue not just to depict nature, but to create moods and emotions. In the late 18th century and 19th century, blue became a popular colour for military uniforms and police uniforms. In the 20th century, because blue was commonly associated with harmony, it was chosen as the colour of the flags of the United Nations and the European Union. Toward the end of the 20th century, dark blue replaced dark grey as the most common colour for business suits; surveys showed that blue was the colour most associated with the masculine, just ahead of black, and was also the colour most associated with intelligence, knowledge, calm and concentration.[5]

Surveys in the US and Europe show that blue is the colour most commonly associated with harmony, faithfulness, confidence, distance, infinity, the imagination, cold, and sometimes with sadness. In US and European public opinion polls it is the most popular colour, chosen by almost half of both men and women as their favourite colour.[6]

Shades and variations

Blue is the colour of light between violet and green on the visible spectrum. Hues of blue include indigo and ultramarine, closer to violet; pure blue, without any mixture of other colours; Cyan, which is midway on the spectrum between blue and green, and the other blue-greens turquoise, teal, and aquamarine.

Blues also vary in shade or tint; darker shades of blue contain black or grey, while lighter tints contain white. Darker shades of blue include ultramarine, cobalt blue, navy blue, and Prussian blue; while lighter tints include sky blue, azure, and Egyptian blue. (For a more complete list see the List of colours).

Blue pigments were originally made from minerals such as lapis lazuli, cobalt and azurite, and blue dyes were made from plants; usually woad in Europe, and Indigofera tinctoria, or true indigo, in Asia and Africa. Today most blue pigments and dyes are made by a chemical process.

Pure blue, also known as high blue, is not mixed with any other colours.

Pure blue, also known as high blue, is not mixed with any other colours. Navy blue, here worn by Admiral Horatio Nelson, is the darkest shade of pure blue.

Navy blue, here worn by Admiral Horatio Nelson, is the darkest shade of pure blue.

Egyptian blue goblet from Mesopotamia, 1500–1300 BC. This was the first synthetic blue, first made in about 2500 BC.

Egyptian blue goblet from Mesopotamia, 1500–1300 BC. This was the first synthetic blue, first made in about 2500 BC. Extract of natural indigo, the most popular blue dye before the invention of synthetic indigo.

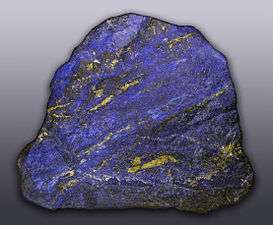

Extract of natural indigo, the most popular blue dye before the invention of synthetic indigo. A block of lapis lazuli, originally used to make ultramarine.

A block of lapis lazuli, originally used to make ultramarine. Ultramarine, slightly violet-blue, in a painting by Giovanni Bellini. It was the most expensive pigment of Renaissance.

Ultramarine, slightly violet-blue, in a painting by Giovanni Bellini. It was the most expensive pigment of Renaissance.

Prussian blue, the colour of the uniforms of the army of Prussia, was invented in about 1706

Prussian blue, the colour of the uniforms of the army of Prussia, was invented in about 1706 Vincent Van Gogh used the synthetic pigment cobalt blue for the sky of his starry night.

Vincent Van Gogh used the synthetic pigment cobalt blue for the sky of his starry night.

Etymology and linguistic differences

The modern English word blue comes from Middle English bleu or blewe, from the Old French bleu, a word of Germanic origin, related to the Old High German word blao.[2] In heraldry, the word azure is used for blue.[7]

In Russian and some other languages, there is no single word for blue, but rather different words for light blue (голубой, goluboy) and dark blue (синий, siniy). See Colour term.

Several languages, including Japanese, Thai, Korean, and Lakota Sioux, use the same word to describe blue and green. For example, in Vietnamese the colour of both tree leaves and the sky is xanh. In Japanese, the word for blue (青 ao) is often used for colours that English speakers would refer to as green, such as the colour of a traffic signal meaning "go". (For more on this subject, see Distinguishing blue from green in language)

History

In the ancient world

Blue was a latecomer among colours used in art and decoration, as well as language and literature.[8] Reds, blacks, browns, and ochres are found in cave paintings from the Upper Paleolithic period, but not blue. Blue was also not used for dyeing fabric until long after red, ochre, pink and purple. This is probably due to the perennial difficulty of making good blue dyes and pigments.[9] The earliest known blue dyes were made from plants – woad in Europe, indigo in Asia and Africa, while blue pigments were made from minerals, usually either lapis lazuli or azurite.

Lapis lazuli, a semi-precious stone, has been mined in Afghanistan for more than three thousand years, and was exported to all parts of the ancient world.[10] In Iran and Mesopotamia, it was used to make jewellery and vessels. In Egypt, it was used for the eyebrows on the funeral mask of King Tutankhamun (1341–1323 BC).[11]

The cost of importing lapis lazuli by caravan across the desert from Afghanistan to Egypt was extremely high. Beginning in about 2500 BC, the ancient Egyptians began to produce their own blue pigment known as Egyptian blue, made by grinding silica, lime, copper, and alkalai, and heating it to 800 or 900 °C (1,470 or 1,650 °F). This is considered the first synthetic pigment.[12] Egyptian blue was used to paint wood, papyrus and canvas, and was used to colour a glaze to make faience beads, inlays, and pots. It was particularly used in funeral statuary and figurines and in tomb paintings. Blue was considered a beneficial colour which would protect the dead against evil in the afterlife. Blue dye was also used to colour the cloth in which mummies were wrapped.[13]

In Egypt blue was associated with the sky and with divinity. The Egyptian god Amun could make his skin blue so that he could fly, invisible, across the sky. Blue could also protect against evil; many people around the Mediterranean still wear a blue amulet, representing the eye of God, to protect them from misfortune.[14]

Blue glass was manufactured in Mesopotamia and Egypt as early as 2500 BC, using the same copper ingredients as Egyptian blue pigment. They also added cobalt, which produced a deeper blue, the same blue produced in the Middle Ages in the stained glass windows of the cathedrals of Saint-Denis and Chartres.[15]

The Ishtar Gate of ancient Babylon (604–562 BC) was decorated with deep blue glazed bricks used as a background for pictures of lions, dragons and aurochs.[16]

The ancient Greeks classified colours by whether they were light or dark, rather than by their hue. The Greek word for dark blue, kyaneos, could also mean dark green, violet, black or brown. The ancient Greek word for a light blue, glaukos, also could mean light green, grey, or yellow.[17]

The Greeks imported indigo dye from India, calling it indikon. They used Egyptian blue in the wall paintings of Knossos, in Crete, (2100 BC). It was not one of the four primary colours for Greek painting described by Pliny the Elder (red, yellow, black, and white), but nonetheless it was used as a background colour behind the friezes on Greek temples and to colour the beards of Greek statues.[18]

The Romans also imported indigo dye, but blue was the colour of working class clothing; the nobles and rich wore white, black, red or violet. Blue was considered the colour of mourning. It was also considered the colour of barbarians; Julius Caesar reported that the Celts and Germans dyed their faces blue to frighten their enemies, and tinted their hair blue when they grew old.[19]

Nonetheless, the Romans made extensive use of blue for decoration. According to Vitruvius, they made dark blue pigment from indigo, and imported Egyptian blue pigment. The walls of Roman villas in Pompeii had frescoes of brilliant blue skies, and blue pigments were found in the shops of colour merchants.[18] The Romans had many different words for varieties of blue, including caeruleus, caesius, glaucus, cyaneus, lividus, venetus, aerius, and ferreus, but two words, both of foreign origin, became the most enduring; blavus, from the Germanic word blau, which eventually became bleu or blue; and azureus, from the Arabic word lazaward, which became azure.[20]

Lapis lazuli pendant from Mesopotamia (c. 2900 BC).

Lapis lazuli pendant from Mesopotamia (c. 2900 BC).- A lapis lazuli bowl from Iran (End of 3rd, beginning 2nd millennium BC)

- A hippo decorated with aquatic plants, made of faience with a blue glaze, made to resemble lapis lazuli. (2033–1710 BC)

Egyptian blue colour in a tomb painting (c. 1500 BC)

Egyptian blue colour in a tomb painting (c. 1500 BC) Egyptian faience bowl (c. 1550 and 1450 BC)

Egyptian faience bowl (c. 1550 and 1450 BC) a decorated cobalt glass vessel from Ancient Egypt (1450–1350 BC)

a decorated cobalt glass vessel from Ancient Egypt (1450–1350 BC)- Figure of a servant from the tomb of King Seth I (1244–1279 BC). The figure is made of faience with a blue glaze, designed to resemble turquoise.

A lion against a blue background from the Ishtar Gate of ancient Babylon. (575 BC)

A lion against a blue background from the Ishtar Gate of ancient Babylon. (575 BC) A Roman wall painting of Venus and her son Eros, from Pompeii (about 30 BC)

A Roman wall painting of Venus and her son Eros, from Pompeii (about 30 BC) Mural in the bedroom of the villa of Fannius Synestor in Boscoreale, (50–40 BC) in the Metropolitan Museum.

Mural in the bedroom of the villa of Fannius Synestor in Boscoreale, (50–40 BC) in the Metropolitan Museum.- A painted pottery pot coloured with Han blue from the Han Dynasty in China (206 BC to 220 AD).

In the Byzantine Empire and the Islamic World

Dark blue was widely used in the decoration of churches in the Byzantine Empire. In Byzantine art Christ and the Virgin Mary usually wore dark blue or purple. Blue was used as a background colour representing the sky in the magnificent mosaics which decorated Byzantine churches.[21]

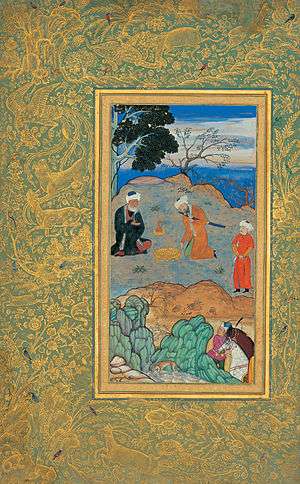

In the Islamic world, blue was of secondary importance to green, believed to be the favourite colour of the Prophet Mohammed. At certain times in Moorish Spain and other parts of the Islamic world, blue was the colour worn by Christians and Jews, because only Muslims were allowed to wear white and green.[22] Dark blue and turquoise decorative tiles were widely used to decorate the facades and interiors of mosques and palaces from Spain to Central Asia. Lapis lazuli pigment was also used to create the rich blues in Persian miniatures.

Blue Byzantine mosaic ceiling representing the night sky in the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, Italy (5th century).

Blue Byzantine mosaic ceiling representing the night sky in the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, Italy (5th century). Blue mosaic in the cloak of Christ in the Hagia Sophia church in Istanbul (13th century).

Blue mosaic in the cloak of Christ in the Hagia Sophia church in Istanbul (13th century).- Glazed stone-paste bowl from Persia (12th century).

Blue tile on the facade of the Friday Mosque in Herat, Afghanistan (15th century).

Blue tile on the facade of the Friday Mosque in Herat, Afghanistan (15th century). Persian miniature from the 16th century.

Persian miniature from the 16th century.

Flower-pattern tile from Iznik, Turkey, from the second half of the 16th century.

Flower-pattern tile from Iznik, Turkey, from the second half of the 16th century.

During the Middle Ages

In the art and life of Europe during the early Middle Ages, blue played a minor role. The nobility wore red or purple, while only the poor wore blue clothing, coloured with poor-quality dyes made from the woad plant. Blue played no part in the rich costumes of the clergy or the architecture or decoration of churches. This changed dramatically between 1130 and 1140 in Paris, when the Abbe Suger rebuilt the Saint Denis Basilica. He installed stained glass windows coloured with cobalt, which, combined with the light from the red glass, filled the church with a bluish violet light. The church became the marvel of the Christian world, and the colour became known as the "bleu de Saint-Denis". In the years that followed even more elegant blue stained glass windows were installed in other churches, including at Chartres Cathedral and Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.[23]

Another important factor in the increased prestige of the colour blue in the 12th century was the veneration of the Virgin Mary, and a change in the colours used to depict her clothing. In earlier centuries her robes had usually been painted in sombre black, grey, violet, dark green or dark blue. In the 12th century the Roma Catholic Church dictated that painters in Italy (and the rest of Europe consequently) to paint the Virgin Mary with the new most expensive pigment imported from Asia; ultramarine. Blue became associated with holiness, humility and virtue.

Ultramarine was made from lapis lazuli, from the mines of Badakshan, in the mountains of Afghanistan, near the source of the Oxus River. The mines were visited by Marco Polo in about 1271; he reported, "here is found a high mountain from which they extract the finest and most beautiful of blues." Ground lapis was used in Byzantine manuscripts as early as the 6th century, but it was impure and varied greatly in colour. Ultramarine refined out the impurities through a long and difficult process, creating a rich and deep blue. It was called bleu outremer in French and blu oltremare in Italian, since it came from the other side of the sea. It cost far more than any other colour, and it became the luxury colour for the Kings and Princes of Europe.[24]

King Louis IX of France, better known as Saint Louis (1214–1270), became the first king of France to regularly dress in blue. This was copied by other nobles. Paintings of the mythical King Arthur began to show him dressed in blue. The coat of arms of the kings of France became an azure or light blue shield, sprinkled with golden fleur-de-lis or lilies. Blue had come from obscurity to become the royal colour.[25]

Once blue became the colour of the king, it also became the colour of the wealthy and powerful in Europe. In the Middle Ages in France and to some extent in Italy, the dyeing of blue cloth was subject to license from the crown or state. In Italy, the dyeing of blue was assigned to a specific guild, the tintori di guado, and could not be done by anyone else without severe penalty. The wearing of blue implied some dignity and some wealth.[26]

Besides ultramarine, several other blues were widely used in the Middle Ages and later in the Renaissance. Azurite, a form of copper carbonate, was often used as a substitute for ultramarine. The Romans used it under the name lapis armenius, or Armenian stone. The British called it azure of Amayne, or German azure. The Germans themselves called it bergblau, or mountain stone. It was mined in France, Hungary, Spain and Germany, and it made a pale blue with a hint of green, which was ideal for painting skies. It was a favourite background colour of the German painter Albrecht Dürer.[27]

Another blue often used in the Middle Ages was called tournesol or folium. It was made from the plant Crozophora tinctoria, which grew in the south of France. It made a fine transparent blue valued in medieval manuscripts.[28]

Another common blue pigment was smalt, which was made by grinding blue cobalt glass into a fine powder. It made a deep violet blue similar to ultramarine, and was vivid in frescoes, but it lost some of its brilliance in oil paintings. It became especially popular in the 17th century, when ultramarine was difficult to obtain. It was employed at times by Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese, El Greco, Van Dyck, Rubens and Rembrandt.[29]

Stained glass windows of the Basilica of Saint Denis (1141–1144).

Stained glass windows of the Basilica of Saint Denis (1141–1144).- Notre Dame de la Belle Verrière window, Chartres Cathedral. (1180–1225).

Detail of the windows at Sainte-Chapelle (1250).

Detail of the windows at Sainte-Chapelle (1250). The Maesta by Duccio (1308) showed the Virgin Mary in a robe painted with ultramarine. Blue became the colour of holiness, virtue and humility.

The Maesta by Duccio (1308) showed the Virgin Mary in a robe painted with ultramarine. Blue became the colour of holiness, virtue and humility..svg.png) In the 12th century blue became part of the royal coat of arms of France.

In the 12th century blue became part of the royal coat of arms of France. The Wilton Diptych, made for King Richard II of England, made lavish use of ultramarine. (About 1400)

The Wilton Diptych, made for King Richard II of England, made lavish use of ultramarine. (About 1400) The Coronation of King Louis VIII of France in 1223 showed that blue had become the royal colour. (painted in 1450).

The Coronation of King Louis VIII of France in 1223 showed that blue had become the royal colour. (painted in 1450).

In the European Renaissance

In the Renaissance, a revolution occurred in painting; artists began to paint the world as it was actually seen, with perspective, depth, shadows, and light from a single source. Artists had to adapt their use of blue to the new rules. In medieval paintings, blue was used to attract the attention of the viewer to the Virgin Mary, and identify her. In Renaissance paintings, artists tried to create harmonies between blue and red, lightening the blue with lead white paint and adding shadows and highlights. Raphael was a master of this technique, carefully balancing the reds and the blues so no one colour dominated the picture.[30]

Ultramarine was the most prestigious blue of the Renaissance, and patrons sometimes specified that it be used in paintings they commissioned. The contract for the Madone des Harpies by Andrea del Sarto (1514) required that the robe of the Virgin Mary be coloured with ultramarine costing "at least five good florins an ounce."[31] Good ultramarine was more expensive than gold; in 1508 the German painter Albrecht Dürer reported in a letter that he had paid twelve ducats – the equivalent of forty-one grams of gold – for just thirty grams of ultramarine.[32]

Often painters or clients saved money by using less expensive blues, such as azurite smalt, or pigments made with indigo, but this sometimes caused problems. Pigments made from azurite were less expensive, but tended to turn dark and green with time. An example is the robe of the Virgin Mary in The Madonna Enthroned with Saints by Raphael in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The Virgin Mary's azurite blue robe has degraded into a greenish-black.[33]

The introduction of oil painting changed the way colours looked and how they were used. Ultramarine pigment, for instance, was much darker when used in oil painting than when used in tempera painting, in frescoes. To balance their colours, Renaissance artists like Raphael added white to lighten the ultramarine. The sombre dark blue robe of the Virgin Mary became a brilliant sky blue.[34] Titian created his rich blues by using many thin glazes of paint of different blues and violets which allowed the light to pass through, which made a complex and luminous colour, like stained glass. He also used layers of finely ground or coarsely ground ultramarine, which gave subtle variations to the blue.[35]

Giotto was one of the first Italian Renaissance painters to use ultramarine, here in the murals of the Arena Chapel in Padua (circa 1305).

Giotto was one of the first Italian Renaissance painters to use ultramarine, here in the murals of the Arena Chapel in Padua (circa 1305). Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, the robes of the Virgin Mary were painted with ultramarine. This is The Virgin of Humility by Fra Angelico (about 1430). Blue fills the picture.

Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, the robes of the Virgin Mary were painted with ultramarine. This is The Virgin of Humility by Fra Angelico (about 1430). Blue fills the picture. In the Madonna of the Meadow (1506), Raphael used white to soften the ultramarine blue of Virgin Mary's robes to balance the red and blue, and to harmonise with the rest of the picture.

In the Madonna of the Meadow (1506), Raphael used white to soften the ultramarine blue of Virgin Mary's robes to balance the red and blue, and to harmonise with the rest of the picture. Titian used an ultramarine sky and robes to give depth and brilliance to Bacchus and Ariadne (1520–1523)

Titian used an ultramarine sky and robes to give depth and brilliance to Bacchus and Ariadne (1520–1523) In this painting of The Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints an early work by Raphael in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the blue cloak of the Virgin Mary has turned a green-black. It was painted with less-expensive azurite.

In this painting of The Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints an early work by Raphael in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the blue cloak of the Virgin Mary has turned a green-black. It was painted with less-expensive azurite..jpg) Glazed Terracotta of The Virgin Adoring the Christ Child, from the workshop of Andrea della Robbia (1483)

Glazed Terracotta of The Virgin Adoring the Christ Child, from the workshop of Andrea della Robbia (1483) The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry was the most important illuminated manuscript of the 15th century. The blue was the extravagantly expensive ultramarine.

The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry was the most important illuminated manuscript of the 15th century. The blue was the extravagantly expensive ultramarine.

Blue and white porcelain

In about the 9th century, Chinese artisans abandoned the Han blue colour they had used for centuries, and began to use cobalt blue, made with cobalt salts of alumina, to manufacture fine blue and white porcelain, The plates and vases were shaped, dried, the paint applied with a brush, covered with a clear glaze, then fired at a high temperature. Beginning in the 14th century, this type of porcelain was exported in large quantity to Europe where it inspired a whole style of art, called Chinoiserie. European courts tried for many years to imitate Chinese blue and white porcelain, but only succeeded in the 18th century after a missionary brought the secret back from China.

Other famous white and blue patterns appeared in Delft, Meissen, Staffordshire, and Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Chinese blue and white porcelain from about 1335, made in Jingdezhen, the porcelain centre of China. Exported to Europe, this porcelain launched the style of Chinoiserie.

Chinese blue and white porcelain from about 1335, made in Jingdezhen, the porcelain centre of China. Exported to Europe, this porcelain launched the style of Chinoiserie. A soft-paste porcelain vase made in Rouen, France, at the end of the 17th century, imitating Chinese blue and white.

A soft-paste porcelain vase made in Rouen, France, at the end of the 17th century, imitating Chinese blue and white. Eighteenth century blue and white pottery from Delft, in the Netherlands.

Eighteenth century blue and white pottery from Delft, in the Netherlands. Russian porcelain of the cobalt net pattern, made with cobalt blue pigment. The Imperial Porcelain Factory in Saint Petersburg was founded in 1744. This pattern, first produced in 1949, was copied after a design made for Catherine the Great.

Russian porcelain of the cobalt net pattern, made with cobalt blue pigment. The Imperial Porcelain Factory in Saint Petersburg was founded in 1744. This pattern, first produced in 1949, was copied after a design made for Catherine the Great.

War of the blues – indigo versus woad

While blue was an expensive and prestigious colour in European painting, it became a common colour for clothing during the Renaissance. The rise of the colour blue in fashion in the 12th and 13th centuries led to a blue dye industry in several cities, notably Amiens, Toulouse, and Erfurt. They made a dye called pastel from woad, a plant common in Europe, which had been used to make blue dye by the Celts and German tribes. Blue became a colour worn by domestics and artisans, not just nobles. In 1570, when Pope Pius V listed the colours that could be used for ecclesiastical dress and for altar decoration, he excluded blue, because he considered it too common.[37]

The process of making blue with woad was long and noxious – it involved soaking the leaves of the plant for from three days to a week in human urine, ideally urine from men who had been drinking a great deal of alcohol, which was said to improve the colour. The fabric was then soaked for a day in the resulting mixture, then put out in the sun, where as it dried it turned blue.[37]

The pastel industry was threatened in the 15th century by the arrival from India of the same dye (indigo), obtained from a shrub widely grown in Asia. The Asian indigo dye precursors is more readily obtained. In 1498, Vasco de Gama opened a trade route to import indigo from India to Europe. In India, the indigo leaves were soaked in water, fermented, pressed into cakes, dried into bricks, then carried to the ports London, Marseille, Genoa, and Bruges. Later, in the 17th century, the British, Spanish, and Dutch established indigo plantations in Jamaica, South Carolina, the Virgin Islands and South America, and began to import American indigo to Europe.

The countries with large and prosperous pastel industries tried to block the use of indigo. The German government outlawed the use of indigo in 1577, describing it as a "pernicious, deceitful and corrosive substance, the Devil's dye."[38][39] In France, Henry IV, in an edict of 1609, forbade under pain of death the use of "the false and pernicious Indian drug".[40] It was forbidden in England until 1611, when British traders established their own indigo industry in India and began to import it into Europe.[41]

The efforts to block indigo were in vain; the quality of indigo blue was too high and the price too low for pastel made from woad to compete. In 1737 both the French and German governments finally allowed the use of indigo. This ruined the dye industries in Toulouse and the other cities that produced pastel, but created a thriving new indigo commerce to seaports such as Bordeaux, Nantes and Marseille.[42]

Another war of the blues took place at the end of the 19th century, between indigo and synthetic indigo, discovered in 1868 by the German chemist Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Adolf von Baeyer. The German chemical firm BASF put the new dye on the market in 1897, in direct competition with the British-run indigo industry in India, which produced most of the world's indigo. In 1897 Britain sold ten thousand tons of natural indigo on the world market, while BASF sold six hundred tons of synthetic indigo. The British industry cut prices and reduced the salaries of its workers, but it was unable to compete; the synthetic indigo was more pure, made a more lasting blue, and was not dependent upon good or bad harvests. In 1911, India sold only 660 tons of natural indigo, while BASF sold 22,000 tons of synthetic indigo. In 2002, more than 38,000 tons of synthetic indigo was produced, often for the production of blue jeans.[43]

- Isatis tinctoria, or woad, was the main source of blue dye in Europe from ancient times until the arrival of indigo from Asia and America. It was processed into a paste called pastel.

- A woad mill in Thuringia, in Germany, in 1752. The woad industry was already on its way to extinction, unable to compete with indigo blue.

A Dutch tapestry from 1495 to 1505. The blue colour comes from woad.

A Dutch tapestry from 1495 to 1505. The blue colour comes from woad. Indigofera tinctoria, a tropical shrub, is the main source of indigo dye. The chemical composition of indigo dye is the same as that of woad, but the colour is more intense.

Indigofera tinctoria, a tropical shrub, is the main source of indigo dye. The chemical composition of indigo dye is the same as that of woad, but the colour is more intense. Cakes of indigo. The leaf has been soaked in water, fermented, mixed with lye or another base, then pressed into cakes and dried, ready for export.

Cakes of indigo. The leaf has been soaked in water, fermented, mixed with lye or another base, then pressed into cakes and dried, ready for export.

Blue uniform

In the 17th century, Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg, was one of the first rulers to give his army blue uniforms. The reasons were economic; the German states were trying to protect their pastel dye industry against competition from imported indigo dye. When Brandenburg became the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701, the uniform colour was adopted by the Prussian army. Most German soldiers wore dark blue uniforms until the First World War, with the exception of the Bavarians, who wore light blue.[44]

Thanks in part to the availability of indigo dye, the 18th century saw the widespread use of blue military uniforms. Prior to 1748, British naval officers simply wore upper-class civilian clothing and wigs. In 1748, the British uniform for naval officers was officially established as an embroidered coat of the colour then called marine blue, now known as navy blue.[45] When the Continental Navy of the United States was created in 1775, it largely copied the British uniform and colour.

In the late 18th century, the blue uniform became a symbol of liberty and revolution. In October 1774, even before the United States declared its independence, George Mason and one hundred Virginia neighbours of George Washington organised a voluntary militia unit (the Fairfax County Independent Company of Volunteers) and elected Washington the honorary commander. For their uniforms they chose blue and buff, the colours of the Whig Party, the opposition party in England, whose policies were supported by George Washington and many other patriots in the American colonies.[46][47]

When the Continental Army was established in 1775 at the outbreak of the American Revolution, the first Continental Congress declared that the official uniform colour would be brown, but this was not popular with many militias, whose officers were already wearing blue. In 1778 the Congress asked George Washington to design a new uniform, and in 1779 Washington made the official colour of all uniforms blue and buff. Blue continued to be the colour of the field uniform of the US Army until 1902, and is still the colour of the dress uniform.[48]

In France the Gardes Françaises, the elite regiment which protected Louis XVI, wore dark blue uniforms with red trim. In 1789, the soldiers gradually changed their allegiance from the king to the people, and they played a leading role in the storming of the Bastille. After the fall of Bastille, a new armed force, the Garde Nationale, was formed under the command of the Marquis de Lafayette, who had served with George Washington in America. Lafayette gave the Garde Nationale dark blue uniforms similar to those of the Continental Army. Blue became the colour of the revolutionary armies, opposed to the white uniforms of the Royalists and the Austrians.[49]

Napoleon Bonaparte abandoned many of the doctrines of the French Revolution but he kept blue as the uniform colour for his army, although he had great difficulty obtaining the blue dye, since the British controlled the seas and blocked the importation of indigo to France. Napoleon was forced to dye uniforms with woad, which had an inferior blue colour.[50] The French army wore a dark blue uniform coat with red trousers until 1915, when it was found to be a too visible target on the battlefields of World War I. It was replaced with uniforms of a light blue-grey colour called horizon blue.

Blue was the colour of liberty and revolution in the 18th century, but in the 19th it increasingly became the colour of government authority, the uniform colour of policemen and other public servants. It was considered serious and authoritative, without being menacing. In 1829, when Robert Peel created the first London Metropolitan Police, he made the colour of the uniform jacket a dark, almost black blue, to make the policemen look different from soldiers, who until then had patrolled the streets. The traditional blue jacket with silver buttons of the London "bobbie" was not abandoned until the mid-1990s, when it was replaced by a light blue shirt and a jumper or sweater of the colour officially known as NATO blue.[51]

The New York City Police Department, modelled after the London Metropolitan Police, was created in 1844, and in 1853, they were officially given a navy blue uniform, the colour they wear today.[52]

Elector Frederic William of Brandenburg gave his soldiers blue uniforms (engraving from 1698). When Brandenburg became the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701, blue became the uniform colour of the Prussian Army.

Elector Frederic William of Brandenburg gave his soldiers blue uniforms (engraving from 1698). When Brandenburg became the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701, blue became the uniform colour of the Prussian Army. Uniform of a lieutenant in the Royal Navy (1777). Marine blue became the official colour of the Royal Navy uniform coat in 1748.

Uniform of a lieutenant in the Royal Navy (1777). Marine blue became the official colour of the Royal Navy uniform coat in 1748. George Washington chose blue and buff as the colours of the Continental Army uniform. They were the colours of the English Whig Party, which Washington admired.

George Washington chose blue and buff as the colours of the Continental Army uniform. They were the colours of the English Whig Party, which Washington admired. The Marquis de Lafayette in the uniform of the Garde Nationale during the French Revolution (1790).

The Marquis de Lafayette in the uniform of the Garde Nationale during the French Revolution (1790).- The cadets of the Ecole Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr, the French military academy, still wear the blue and red uniform of the French army before 1915.

In 1853, New York policemen and firemen were officially outfitted in navy blue uniforms.

In 1853, New York policemen and firemen were officially outfitted in navy blue uniforms. Metropolitan Police officers in Soho, London (2007).

Metropolitan Police officers in Soho, London (2007).

Search for the perfect blue

During the 17th and 18th centuries, chemists in Europe tried to discover a way to create synthetic blue pigments, avoiding the expense of importing and grinding lapis lazuli, azurite and other minerals. The Egyptians had created a synthetic colour, Egyptian blue, three thousand years BC, but the formula had been lost. The Chinese had also created synthetic pigments, but the formula was not known in the west.

In 1709 a German druggist and pigment maker named Diesbach accidentally discovered a new blue while experimenting with potassium and iron sulphides. The new colour was first called Berlin blue, but later became known as Prussian blue. By 1710 it was being used by the French painter Antoine Watteau, and later his successor Nicolas Lancret. It became immensely popular for the manufacture of wallpaper, and in the 19th century was widely used by French impressionist painters.[53]

Beginning in the 1820s, Prussian blue was imported into Japan through the port of Nagasaki. It was called bero-ai, or Berlin blue, and it became popular because it did not fade like traditional Japanese blue pigment, ai-gami, made from the dayflower. Prussian blue was used by both Hokusai, in his famous wave paintings, and Hiroshige.[54]

In 1824 the Societé pour l'Encouragement d'Industrie in France offered a prize for the invention of an artificial ultramarine which could rival the natural colour made from lapis lazuli. The prize was won in 1826 by a chemist named Jean Baptiste Guimet, but he refused to reveal the formula of his colour. In 1828, another scientist, Christian Gmelin then a professor of chemistry in Tübingen, found the process and published his formula. This was the beginning of new industry to manufacture artificial ultramarine, which eventually almost completely replaced the natural product.[55]

In 1878 a German chemist named a. Von Baeyer discovered a synthetic substitute for indigotine, the active ingredient of indigo. This product gradually replaced natural indigo, and after the end of the First World War, it brought an end to the trade of indigo from the East and West Indies.

In 1901 a new synthetic blue dye, called Indanthrone blue, was invented, which had even greater resistance to fading during washing or in the sun. This dye gradually replaced artificial indigo, whose production ceased in about 1970. Today almost all blue clothing is dyed with an indanthrone blue.[56]

The 19th-century Japanese woodblock artist Hokusai used Prussian blue, a synthetic colour imported from Europe, in his wave paintings.

The 19th-century Japanese woodblock artist Hokusai used Prussian blue, a synthetic colour imported from Europe, in his wave paintings.- A synthetic indigo dye factory in Germany in 1890. The manufacture of this dye ended the trade in indigo from America and India that had begun in the 15th century.

Impressionist painters

The invention of new synthetic pigments in the 18th and 19th centuries considerably brightened and expanded the palette of painters. J.M.W. Turner experimented with the new cobalt blue, and of the twenty colours most used by the Impressionists, twelve were new and synthetic colours, including cobalt blue, ultramarine and cerulean blue.[57]

Another important influence on painting in the 19th century was the theory of complementary colours, developed by the French chemist Michel Eugene Chevreul in 1828 and published in 1839. He demonstrated that placing complementary colours, such as blue and yellow-orange or ultramarine and yellow, next to each other heightened the intensity of each colour "to the apogee of their tonality."[58] In 1879 an American physicist, Ogden Rood, published a book charting the complementary colours of each colour in the spectrum.[59] This principle of painting was used by Claude Monet in his Impression – Sunrise – Fog (1872), where he put a vivid blue next to a bright orange sun, (1872) and in Régate à Argenteuil (1872), where he painted an orange sun against blue water. The colours brighten each other. Renoir used the same contrast of cobalt blue water and an orange sun in Canotage sur la Seine (1879–1880). Both Monet and Renoir liked to use pure colours, without any blending.[57]

Monet and the impressionists were among the first to observe that shadows were full of colour. In his La Gare Saint-Lazare, the grey smoke, vapour and dark shadows are actually composed of mixtures of bright pigment, including cobalt blue, cerulean blue, synthetic ultramarine, emerald green, Guillet green, chrome yellow, vermilion and ecarlate red.[60] Blue was a favourite colour of the impressionist painters, who used it not just to depict nature but to create moods, feelings and atmospheres. Cobalt blue, a pigment of cobalt oxide-aluminium oxide, was a favourite of Auguste Renoir and Vincent van Gogh. It was similar to smalt, a pigment used for centuries to make blue glass, but it was much improved by the French chemist Louis Jacques Thénard, who introduced it in 1802. It was very stable but extremely expensive. Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo, "'Cobalt [blue] is a divine colour and there is nothing so beautiful for putting atmosphere around things ..."[61]

Van Gogh described to his brother Theo how he composed a sky: "The dark blue sky is spotted with clouds of an even darker blue than the fundamental blue of intense cobalt, and others of a lighter blue, like the bluish white of the Milky Way ... the sea was very dark ultramarine, the shore a sort of violet and of light red as I see it, and on the dunes, a few bushes of prussian blue."[62]

Claude Monet used several recently invented colours in his Gare Saint-Lazare (1877). He used cobalt blue, invented in 1807, cerulean blue invented in 1860, and French ultramarine, first made in 1828.

Claude Monet used several recently invented colours in his Gare Saint-Lazare (1877). He used cobalt blue, invented in 1807, cerulean blue invented in 1860, and French ultramarine, first made in 1828. In Régate à Argenteuil (1872), Monet used two complementary colours together — blue and orange — to brighten the effect of both colours.

In Régate à Argenteuil (1872), Monet used two complementary colours together — blue and orange — to brighten the effect of both colours. The Umbrellas, by Pierre Auguste-Renoir. (1881 and 1885). Renoir used cobalt blue for right side of the picture, but used the new synthetic ultramarine introduced in the 1870s, when he added two figures to left of the picture a few years later.

The Umbrellas, by Pierre Auguste-Renoir. (1881 and 1885). Renoir used cobalt blue for right side of the picture, but used the new synthetic ultramarine introduced in the 1870s, when he added two figures to left of the picture a few years later. In Vincent van Gogh's Irises, the blue irises are placed against their complementary colour, yellow-orange.

In Vincent van Gogh's Irises, the blue irises are placed against their complementary colour, yellow-orange. Van Gogh's Starry Night Over the Rhone (1888). Blue used to create a mood or atmosphere. A cobalt blue sky, and cobalt or ultramarine water.

Van Gogh's Starry Night Over the Rhone (1888). Blue used to create a mood or atmosphere. A cobalt blue sky, and cobalt or ultramarine water. Wheatfield Under Thunderclouds (July 1890), One of the last paintings by Vincent van Gogh, He wrote of cobalt blue, "there is nothing so beautiful for putting atmosphere around things."

Wheatfield Under Thunderclouds (July 1890), One of the last paintings by Vincent van Gogh, He wrote of cobalt blue, "there is nothing so beautiful for putting atmosphere around things."

Blue suit

Blue had first become the high fashion colour of the wealthy and powerful in Europe in the 13th century, when it was worn by Louis IX of France, better known as Saint Louis (1214-1270). Wearing blue implied dignity and wealth, and blue clothing was restricted to the nobility.[63] However, blue was replaced by black as the power colour in the 14th century, when European princes, and then merchants and bankers, wanted to show their seriousness, dignity and devoutness (see Black).

Blue gradually returned to court fashion in the 17th century, as part of a palette of peacock-bright colours shown off in extremely elaborate costumes. The modern blue business suit has its roots in England in the middle of the 17th century. Following the London plague of 1665 and the London fire of 1666, King Charles II of England ordered that his courtiers wear simple coats, waistcoats and breeches, and the palette of colours became blue, grey, white and buff. Widely imitated, this style of men's fashion became almost a uniform of the London merchant class and the English country gentleman.[64]

During the American Revolution, the leader of the Whig Party in England, Charles James Fox, wore a blue coat and buff waistcoat and breeches, the colours of the Whig Party and of the uniform of George Washington, whose principles he supported. The men's suit followed the basic form of the military uniforms of the time, particularly the uniforms of the cavalry.[64]

In the early 19th century, during the Regency of the future King George IV, the blue suit was revolutionised by a courtier named George Beau Brummel. Brummel created a suit that closely fitted the human form. The new style had a long tail coat cut to fit the body and long tight trousers to replace the knee-length breeches and stockings of the previous century. He used plain colours, such as blue and grey, to concentrate attention on the form of the body, not the clothes. Brummel observed, "If people turn to look at you in the street, you are not well dressed."[65] This fashion was adopted by the Prince Regent, then by London society and the upper classes. Originally the coat and trousers were different colours, but in the 19th century the suit of a single colour became fashionable. By the late 19th century the black suit had become the uniform of businessmen in England and America. In the 20th century, the black suit was largely replaced by the dark blue or grey suit.[64]

King Louis IX of France (on the right, with Pope Innocent) was the first European king to wear blue. It quickly became the colour of the nobles and wealthy.

King Louis IX of France (on the right, with Pope Innocent) was the first European king to wear blue. It quickly became the colour of the nobles and wealthy. Joseph Leeson, later 1st Earl of Milltown, in the typical dress of the English country gentleman in the 1730s.

Joseph Leeson, later 1st Earl of Milltown, in the typical dress of the English country gentleman in the 1730s. Charles James Fox, a leader of the Whig Party in England, wore a blue suit in Parliament in support of George Washington and the American Revolution. Portrait by Joshua Reynolds (1782).

Charles James Fox, a leader of the Whig Party in England, wore a blue suit in Parliament in support of George Washington and the American Revolution. Portrait by Joshua Reynolds (1782). Beau Brummel introduced the ancestor of the modern blue suit, shaped to the body. (1805).

Beau Brummel introduced the ancestor of the modern blue suit, shaped to the body. (1805). Man's suit, 1826. Dark blue suits were still rare; this one is blue-green or teal.

Man's suit, 1826. Dark blue suits were still rare; this one is blue-green or teal. Man's blue suit in the 1870s, Paris. Painting by Caillebotte.

Man's blue suit in the 1870s, Paris. Painting by Caillebotte._Christmas_tree_-_Jack_and_Jacqueline_Kennedy.jpg) President John F. Kennedy popularised the blue two-button business suit, less formal than the suits of his predecessors. (1961)

President John F. Kennedy popularised the blue two-button business suit, less formal than the suits of his predecessors. (1961) In the 21st century, the dark blue business suit is the most common style worn by world leaders, seen here at the 2011 G-20 Summit in Cannes, France.

In the 21st century, the dark blue business suit is the most common style worn by world leaders, seen here at the 2011 G-20 Summit in Cannes, France.

In the 20th and 21st century

At the beginning of the 20th century, many artists recognised the emotional power of blue, and made it the central element of paintings. During his Blue Period (1901–1904) Pablo Picasso used blue and green, with hardly any warm colours, to create a melancholy mood. In Russia, the symbolist painter Pavel Kuznetsov and the Blue Rose art group (1906–1908) used blue to create a fantastic and exotic atmosphere. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky and other Russian émigrés formed the art group called Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), and used blue to symbolise spirituality and eternity.[66] Henri Matisse used intense blues to express the emotions he wanted viewers to feel. Matisse wrote, "A certain blue penetrates your soul."[67]

In the art of the second half of the 20th century, painters of the abstract expressionist movement began to use blue and other colours in pure form, without any attempt to represent anything, to inspire ideas and emotions. Painter Mark Rothko observed that colour was "only an instrument;" his interest was "in expressing human emotions tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on."[68]

In fashion blue, particularly dark blue, was seen as a colour which was serious but not grim. In the mid-20th century, blue passed black as the most common colour of men's business suits, the costume usually worn by political and business leaders. Public opinion polls in the United States and Europe showed that blue was the favourite colour of over fifty per cent of respondents. Green was far behind with twenty per cent, while white and red received about eight per cent each.[69]

In 1873 a German immigrant in San Francisco, Levi Strauss, invented a sturdy kind of work trousers, made of denim fabric and coloured with indigo dye, called blue jeans. In 1935, they were raised to the level of high fashion by Vogue magazine. Beginning in the 1950s, they became an essential part of uniform of young people in the United States, Europe, and around the world.

Blue was also seen as a colour which was authoritative without being threatening. Following the Second World War, blue was adopted as the colour of important international organisations, including the United Nations, the Council of Europe, UNESCO, the European Union, and NATO. United Nations peacekeepers wear blue helmets to stress their peacekeeping role. Blue is used by the NATO Military Symbols for Land Based Systems to denote friendly forces, hence the term "blue on blue" for friendly fire, and Blue Force Tracking for location of friendly units. The People's Liberation Army of China (formerly known as the "Red Army") uses the term "Blue Army" to refer to hostile forces during exercises.[70]

The 20th century saw the invention of new ways of creating blue, such as chemiluminescence, making blue light through a chemical reaction.

In the 20th century, it also became possible to own your own colour of blue. The French artist Yves Klein, with the help of a French paint dealer, created a specific blue called International Klein blue, which he patented. It was made of ultramarine combined with a resin called Rhodopa, which gave it a particularly brilliant colour. The baseball team the Los Angeles Dodgers developed its own blue, called Dodger blue, and several American universities invented new blues for their colours.

With the dawn of the World Wide Web, blue has become the standard colour for hyperlinks in graphic browsers (though in most browsers links turn purple if you visit their target), to make their presence within text obvious to readers.

During his Blue Period, Pablo Picasso used blue as the colour of melancholy.

During his Blue Period, Pablo Picasso used blue as the colour of melancholy. The Russian avant-garde painter Pavel Kuznetsov and his group, the Blue Rose, used blue to symbolise fantasy and exoticism. This is In the Steppe – Mirage (1911).

The Russian avant-garde painter Pavel Kuznetsov and his group, the Blue Rose, used blue to symbolise fantasy and exoticism. This is In the Steppe – Mirage (1911).%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_52.1_x_54.6_cm%2C_Stiftung_Sammlung_E.G._B%C3%BChrle%2C_Zurich.jpg) The Blue Rider (1903), by Wassily Kandinsky, For Kandinsky, blue was the colour of spirituality: the darker the blue, the more it awakened human desire for the eternal.[66]

The Blue Rider (1903), by Wassily Kandinsky, For Kandinsky, blue was the colour of spirituality: the darker the blue, the more it awakened human desire for the eternal.[66] The Conversation (1908–1912) by Henri Matisse used blue to express the emotions he wanted the viewer to feel.

The Conversation (1908–1912) by Henri Matisse used blue to express the emotions he wanted the viewer to feel. Blue jeans, made of denim coloured with indigo dye, patented by Levi Strauss in 1873, became an essential part of the wardrobe of young people beginning in the 1950s.

Blue jeans, made of denim coloured with indigo dye, patented by Levi Strauss in 1873, became an essential part of the wardrobe of young people beginning in the 1950s. Blue is the colour of United Nations peacekeepers, known as Blue Helmets.

Blue is the colour of United Nations peacekeepers, known as Blue Helmets. Vivid blues can be created by chemical reactions, called chemiluminescence. This is luminol, a chemical used in crime scene investigations. Luminol glows blue when it contacts even a tiny trace of blood.

Vivid blues can be created by chemical reactions, called chemiluminescence. This is luminol, a chemical used in crime scene investigations. Luminol glows blue when it contacts even a tiny trace of blood. Blue neon lighting, first used in commercial advertising, is now used in works of art. This is Zwei Pferde für Münster (Two horses for Münster), a neon sculpture by Stephan Huber (2002), in Munster, Germany.

Blue neon lighting, first used in commercial advertising, is now used in works of art. This is Zwei Pferde für Münster (Two horses for Münster), a neon sculpture by Stephan Huber (2002), in Munster, Germany.

In science and industry

Pigments and dyes

Blue pigments were made from minerals, especially lapis lazuli and azurite (Cu

3(CO

3)

2(OH)

2). These minerals were crushed, ground into powder, and then mixed with a quick-drying binding agent, such as egg yolk (tempera painting); or with a slow-drying oil, such as linseed oil, for oil painting. To make blue stained glass, cobalt blue (cobalt(II) aluminate: CoAl

2O

4)pigment was mixed with the glass. Other common blue pigments made from minerals are ultramarine (Na8-10Al

6Si

6O

24S2-4), cerulean blue (primarily cobalt (II) stanate: Co

2SnO

4), and Prussian blue (milori blue: primarily Fe

7(CN)

18).

Natural dyes to colour cloth and tapestries were made from plants. Woad and true indigo were used to produce indigo dye used to colour fabrics blue or indigo. Since the 18th century, natural blue dyes have largely been replaced by synthetic dyes.

Lapis lazuli, mined in Afghanistan for more than three thousand years, was used for jewellery and ornaments, and later was crushed and powdered and used as a pigment. The more it was ground, the lighter the blue colour became.

Lapis lazuli, mined in Afghanistan for more than three thousand years, was used for jewellery and ornaments, and later was crushed and powdered and used as a pigment. The more it was ground, the lighter the blue colour became. Azurite, common in Europe and Asia, is produced by the weathering of copper ore deposits. It was crushed and powdered and used as a pigment from ancient times,

Azurite, common in Europe and Asia, is produced by the weathering of copper ore deposits. It was crushed and powdered and used as a pigment from ancient times, Natural ultramarine, made by grinding and purifying lapis lazuli, was the finest available blue pigment in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. It was extremely expensive, and in Italian Renaissance art, it was often reserved the robes of the Virgin Mary.

Natural ultramarine, made by grinding and purifying lapis lazuli, was the finest available blue pigment in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. It was extremely expensive, and in Italian Renaissance art, it was often reserved the robes of the Virgin Mary. Egyptian blue, the first artificial pigment, created in the third millennium BC in Ancient Egypt by grinding sand, copper and natron, and then heating them. It was often used in tomb paintings and funereal objects to protect the dead in their afterlife.

Egyptian blue, the first artificial pigment, created in the third millennium BC in Ancient Egypt by grinding sand, copper and natron, and then heating them. It was often used in tomb paintings and funereal objects to protect the dead in their afterlife. Ground azurite was often in Renaissance used as a substitute for the much more expensive lapis lazuli. It made a rich blue, but was unstable and could turn dark green over time.

Ground azurite was often in Renaissance used as a substitute for the much more expensive lapis lazuli. It made a rich blue, but was unstable and could turn dark green over time.- Cerulean was created with copper and cobalt oxide, and used to make a sky blue colour. Like azurite, it could fade or turn green.

- Cobalt blue. Cobalt has been used for centuries to colour glass and ceramics; it was used to make the deep blue stained glass windows of Gothic cathedrals and Chinese porcelain beginning in the T'ang Dynasty. In 1799 a French chemist, Louis Jacques Thénard, made a synthetic cobalt blue pigment which became immensely popular with painters.

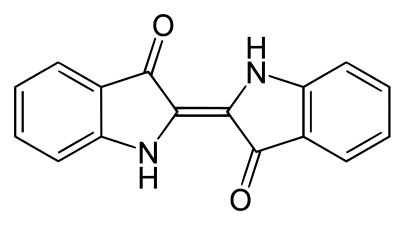

Indigo dye is made from the woad, Indigofera tinctoria, a plant common in Asia and Africa but little known in Europe until the 15th century. Its importation into Europe revolutionised the colour of clothing. It also became the colour used in blue denim and jeans. Nearly all indigo dye produced today is synthetic.

Indigo dye is made from the woad, Indigofera tinctoria, a plant common in Asia and Africa but little known in Europe until the 15th century. Its importation into Europe revolutionised the colour of clothing. It also became the colour used in blue denim and jeans. Nearly all indigo dye produced today is synthetic. Chemical structure of indigo dye, a widely produced blue dye. Blue jeans consist of 1–3% by weight of this organic compound.

Chemical structure of indigo dye, a widely produced blue dye. Blue jeans consist of 1–3% by weight of this organic compound. Synthetic ultramarine pigment, invented in 1826, has the same chemical composition as natural ultramarine. It is more vivid than natural ultramarine because the particles are smaller and more uniform in size, and thus distribute the light more evenly.

Synthetic ultramarine pigment, invented in 1826, has the same chemical composition as natural ultramarine. It is more vivid than natural ultramarine because the particles are smaller and more uniform in size, and thus distribute the light more evenly. A new synthetic blue created in the 1930s is phthalocyanine, an intense colour widely used for making blue ink, dye, and pigment.

A new synthetic blue created in the 1930s is phthalocyanine, an intense colour widely used for making blue ink, dye, and pigment.

Optics

| | ||

|---|---|---|

| Colour | Frequency | Wavelength |

| violet | 668–789 THz | 380–450 nm |

| blue | 606–668 THz | 450–495 nm |

| green | 526–606 THz | 495–570 nm |

| yellow | 508–526 THz | 570–590 nm |

| orange | 484–508 THz | 590–620 nm |

| red | 400–484 THz | 620–750 nm |

Human eyes perceive blue when observing light which has a wavelength between 450–495 nanometres. Blues with a higher frequency and thus a shorter wavelength gradually look more violet, while those with a lower frequency and a longer wavelength gradually appear more green. Pure blue, in the middle, has a wavelength of 470 nanometres.

Isaac Newton included blue as one of the seven colours in his first description the visible spectrum, He chose seven colours because that was the number of notes in the musical scale, which he believed was related to the optical spectrum. He included indigo, the hue between blue and violet, as one of the separate colours, though today it is usually considered a hue of blue.[71]

In painting and traditional colour theory, blue is one of the three primary colours of pigments (red, yellow, blue), which can be mixed to form a wide gamut of colours. Red and blue mixed together form violet, blue and yellow together form green. Mixing all three primary colours together produces a dark grey. From the Renaissance onwards, painters used this system to create their colours. (See RYB colour system.)

The RYB model was used for colour printing by Jacob Christoph Le Blon as early as 1725. Later, printers discovered that more accurate colours could be created by using combinations of magenta, cyan, yellow and black ink, put onto separate inked plates and then overlaid one at a time onto paper. This method could produce almost all the colours in the spectrum with reasonable accuracy.

In the 19th century the Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell found a new way of explaining colours, by the wavelength of their light. He showed that white light could be created by combining red, blue and green light, and that virtually all colours could be made by different combinations of these three colours. His idea, called additive colour or the RGB colour model, is used today to create colours on televisions and computer screens. The screen is covered by tiny pixels, each with three fluorescent elements for creating red, green and blue light. If the red, blue and green elements all glow at once, the pixel looks white. As the screen is scanned from behind with electrons, each pixel creates its own designated colour, composing a complete picture on the screen.

Additive colour mixing. The projection of primary colour lights on a screen shows secondary colours where two overlap; the combination red, green, and blue each in full intensity makes white.

Additive colour mixing. The projection of primary colour lights on a screen shows secondary colours where two overlap; the combination red, green, and blue each in full intensity makes white. Blue and orange pixels on an LCD television screen. Closeup of the red, green and blue sub-pixels on left.

Blue and orange pixels on an LCD television screen. Closeup of the red, green and blue sub-pixels on left.

On the HSV colour wheel, the complement of blue is yellow; that is, a colour corresponding to an equal mixture of red and green light. On a colour wheel based on traditional colour theory (RYB) where blue was considered a primary colour, its complementary colour is considered to be orange (based on the Munsell colour wheel).[72]

Scientific natural standards

- Emission spectrum of Cu2+

- Electronic spectrum of aqua-ions Cu(H

2O)2+

6

Why the sky and sea appear blue

Of the colours in the visible spectrum of light, blue has a very short wavelength, while red has the longest wavelength. When sunlight passes through the atmosphere, the blue wavelengths are scattered more widely by the oxygen and nitrogen molecules, and more blue comes to our eyes. This effect is called Rayleigh scattering, after Lord Rayleigh, the British physicist who discovered it. It was confirmed by Albert Einstein in 1911.[73]

Near sunrise and sunset, most of the light we see comes in nearly tangent to the Earth's surface, so that the light's path through the atmosphere is so long that much of the blue and even green light is scattered out, leaving the sun rays and the clouds it illuminates red. Therefore, when looking at the sunset and sunrise, the colour red is more perceptible than any of the other colours.[74]

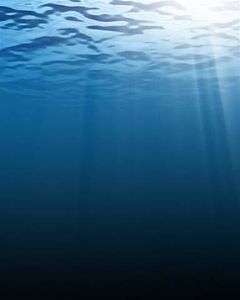

The sea is seen as blue for largely the same reason: the water absorbs the longer wavelengths of red and reflects and scatters the blue, which comes to the eye of the viewer. The colour of the sea is also affected by the colour of the sky, reflected by particles in the water; and by algae and plant life in the water, which can make it look green; or by sediment, which can make it look brown.[75]

Atmospheric perspective

The farther away an object is, the more blue it often appears to the eye. For example, mountains in the distance often appear blue. This is the effect of atmospheric perspective; the farther an object is away from the viewer, the less contrast there is between the object and its background colour, which is usually blue. In a painting where different parts of the composition are blue, green and red, the blue will appear to be more distant, and the red closer to the viewer. The cooler a colour is, the more distant it seems.[76]

Blue light is scattered more than other wavelengths by the gases in the atmosphere, giving the Earth a blue halo when seen from space.

Blue light is scattered more than other wavelengths by the gases in the atmosphere, giving the Earth a blue halo when seen from space.- An example of aerial, or atmospheric perspective. Objects become more blue and lighter in colour the farther they are from the viewer, because of Rayleigh scattering.

Under the sea, red and other light with longer wavelengths is absorbed, so white objects appear blue. The deeper you go, the darker the blue becomes. In the open sea, only about one per cent of light penetrates to a depth of 200 metres. (See underwater and euphotic depth)

Under the sea, red and other light with longer wavelengths is absorbed, so white objects appear blue. The deeper you go, the darker the blue becomes. In the open sea, only about one per cent of light penetrates to a depth of 200 metres. (See underwater and euphotic depth)

Blue eyes

Blue eyes do not actually contain any blue pigment. Eye colour is determined by two factors: the pigmentation of the eye's iris[77][78] and the scattering of light by the turbid medium in the stroma of the iris.[79] In humans, the pigmentation of the iris varies from light brown to black. The appearance of blue, green, and hazel eyes results from the Rayleigh scattering of light in the stroma, an optical effect similar to what accounts for the blueness of the sky.[79][80] The irises of the eyes of people with blue eyes contain less dark melanin than those of people with brown eyes, which means that they absorb less short-wavelength blue light, which is instead reflected out to the viewer. Eye colour also varies depending on the lighting conditions, especially for lighter-coloured eyes.

Blue eyes are most common in Ireland, the Baltic Sea area and Northern Europe,[81] and are also found in Eastern, Central, and Southern Europe. Blue eyes are also found in parts of Western Asia, most notably in Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, and Iran.[82] In Estonia, 99% of people have blue eyes.[83][84] In Denmark 30 years ago, only 8% of the population had brown eyes, though through immigration, today that number is about 11%. In Germany, about 75% have blue eyes.[84]

In the United States, as of 2006, one out of every six people, or 16.6% of the total population, and 22.3% of the white population, have blue eyes, compared with about half of Americans born in 1900, and a third of Americans born in 1950. Blue eyes are becoming less common among American children. In the US, boys are 3–5 per cent more likely to have blue eyes than girls.[81]

Lasers

Lasers emitting in the blue region of the spectrum became widely available to the public in 2010 with the release of inexpensive high-powered 445-447 nm laser diode technology.[85] Previously the blue wavelengths were accessible only through DPSS which are comparatively expensive and inefficient, however these technologies are still widely used by the scientific community for applications including optogenetics, Raman spectroscopy, and particle image velocimetry, due to their superior beam quality.[86] Blue gas lasers are also still commonly used for holography, DNA sequencing, optical pumping, and other scientific and medical applications.

In nature

Blue compounds are relatively rare in nature.[87]

Lactarius indigo, or the blue milk mushroom

Lactarius indigo, or the blue milk mushroom

Blue seeds of the Ravenala tree from Madagascar

Blue seeds of the Ravenala tree from Madagascar The Morpho peleides butterfly. The blue is caused by iridescence, the diffraction of light from millions of tiny scales on the wings. The colour is intended to frighten predators.

The Morpho peleides butterfly. The blue is caused by iridescence, the diffraction of light from millions of tiny scales on the wings. The colour is intended to frighten predators..jpg)

Dried crystals of copper sulphate

Dried crystals of copper sulphate

_Edit.jpg) Dendrobates azureus, the poison dart frog from Brazil. Its skin contains alkaloids, which can paralyse or kill predators.

Dendrobates azureus, the poison dart frog from Brazil. Its skin contains alkaloids, which can paralyse or kill predators.

A blue whale, the largest known animal to have ever existed, seen from above. The back is a pale blue grey.

A blue whale, the largest known animal to have ever existed, seen from above. The back is a pale blue grey..jpg) Blue carpet of Lupinus pilosus.

Blue carpet of Lupinus pilosus.- Blue Anemone coronaria.

The body feathers of Pavo cristatus (peacock) are coloured with shining blue.

The body feathers of Pavo cristatus (peacock) are coloured with shining blue.

Animals

- When an animal's coat is described as "blue", it usually refers to a shade of grey that takes on a bluish tint, a diluted variant of a pure black coat. This designation is used for a variety of animals, including dog coats, some rat coats, cat coats, some chicken breeds, some horse coat colours and rabbit coat colours. Some animals, such as giraffes and lizards, also have blue tongues.

In world culture

- In the English language, blue often represents the human emotion of sadness, for example, "He was feeling blue".

- In German, to be "blue" (blau sein) is to be drunk. This derives from the ancient use of urine, particularly the urine of men who had been drinking alcohol in dyeing cloth blue with woad or indigo.[88] It may also be in relation to rain, which is usually regarded as a trigger of depressive emotions.[89]

- Blue can sometimes represent happiness and optimism in popular songs,[90] usually referring to blue skies.[91]

- In German, a person who regularly looks upon the world with a blue eye is a person who is rather naive.[92]

- Blue is commonly used in the Western Hemisphere to symbolise boys, in contrast to pink used for girls. In the early 1900s, blue was the colour for girls, since it had traditionally been the colour of the Virgin Mary in Western Art, while pink was for boys (as it was akin to the colour red, considered a masculine colour).[93]

- In China, the colour blue is commonly associated with torment, ghosts, and death.[94] In a traditional Chinese opera, a character with a face powdered blue is a villain.[95]

- In Turkey and Central Asia, blue is the colour of mourning.[94]

- The men of the Tuareg people in North Africa wear a blue turban called a tagelmust, which protects them from the sun and wind-blown sand of the Sahara desert. It is coloured with indigo. Instead of using dye, which uses precious water, the tagelmust is coloured by pounding it with powdered indigo. The blue colour transfers to the skin, where it is seen as a sign of nobility and affluence.[96] Early visitors called them the "Blue Men" of the Sahara.[97]

- In the culture of the Hopi people of the American southwest, blue symbolised the west, which was seen as the house of death. A dream about a person carrying a blue feather was considered a very bad omen.[94]

- In Thailand, blue is associated with Friday on the Thai solar calendar. Anyone may wear blue on Fridays and anyone born on a Friday may adopt blue as their colour.

- A man of the Tuareg people of North Africa wears a tagelmust or turban dyed with indigo. The indigo stains their skin blue; they were known by early visitors as "the blue men" of the desert.

As a national and international colour

Various shades of blue are used as the national colours for many nations.

- Azure, a light blue, is the national colour of Italy (from the livery colour of the former reigning family, the House of Savoy). National sport clubs are known as the Azzurri.

- Blue and white are the national colours of Scotland, Argentina, El Salvador, Finland, Greece, Guatemala, Honduras, Israel, Micronesia, Nicaragua and Somalia, are the ancient national colours of Portugal and are the colours of the United Nations.

- Blue, white and yellow are the national colours of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and Uruguay.

- Blue, white and green are the national colours of Sierra Leone.

- Blue, white and black are the national colours of Estonia.[98]

- Blue and yellow are the national colours of Barbados, Kazakhstan, Palau, Sweden, and Ukraine.

- Blue, yellow and green are the national colours of Brazil, Gabon, and Rwanda.

- Blue, yellow and red are the national colours of Chad, Colombia, Ecuador, Moldova, Romania, and Venezuela.

- Blue and red are the national colours of Haiti and Liechtenstein.

- Blue, red and white are the national colours of Australia, Cambodia, Costa Rica, Chile, Croatia, Cuba, the Czech Republic, the Dominican Republic, France, Iceland, North Korea, Laos, Liberia, Luxembourg, Nepal, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Panama, Paraguay, Puerto Rico, Russia, Samoa, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

- Blue, called St. Patrick's blue, is a traditional colour of Ireland, and appears on the Arms of Ireland.

Politics

- In the Byzantine Empire, the Blues and the Greens were the most prominent political factions in the capital. They took their names from the colours of the two most popular chariot racing teams at the Hippodrome of Constantinople.[99]

- The word blue was used in England the 17th century as a disparaging reference to rigid moral codes and those who observed them, particularly in blue-stocking, a reference to Oliver Cromwell's supporters in the parliament of 1653.

- In the middle of the 18th century, blue was the colour of Tory party, then the opposition party in England, Scotland and Ireland, which supported the British monarch and power of the landed aristocracy, while the ruling Whigs had orange as their colour. Flags of the two colours are seen over a polling station in the series of prints by William Hogarth called Humours of an election, made in 1754–55. Blue remains the colour of the Conservative Party of the UK today.

- By the time of the American Revolution, The Tories were in power and blue and buff had become the colours of the opposition Whigs. They were the subject of a famous toast to Whig politicians by Mrs. Crewe in 1784; "Buff and blue and all of you." They also became the colours of the American patriots in the American Revolution, who had strong Whig sympathies, and of the uniforms of Continental Army led by George Washington.[100]

- During the French Revolution and the revolt in the Vendée that followed, blue was the colour worn by the soldiers of the Revolutionary government, while the royalists wore white.

- The Breton blues were members of a liberal, anti-clerical political movement in Brittany in the late 19th century.

- The blueshirts were members of an extreme right paramilitary organisation active in Ireland during the 1930s.

- Blue is associated with numerous centre-right liberal political parties in Europe, including the People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (Netherlands), the Reformist Movement and Open VLD (Belgium), the Democratic Party (Luxembourg), Liberal Party (Denmark) and Liberal People's Party (Sweden).

- Blue is the colour of the Conservative Party in Britain and Conservative Party of Canada.

- In the United States, television commentators use the term "blue states" for those states which traditionally vote for the Democratic Party in presidential elections, and "red states" for those which vote for the Republican Party.[101]

- In Québec Province of Canada, the Blues are those who support sovereignty for Quebec, as opposed to the Federalists. It is the colour of the Parti québécois and the Parti libéral du Québec.

- Blue is the colour of the New Progressive Party of Puerto Rico.

- In Brazil, blue states are the ones in which the Social Democratic Party has the majority, in opposition to the Workers' Party, usually represented by red.

- A blue law is a type of law, typically found in the United States and Canada, designed to enforce religious standards, particularly the observance of Sunday as a day of worship or rest, and a restriction on Sunday shopping.

- The Blue House is the residence of the President of South Korea.[102]

An illustration by William Hogarth from 1854 shows a polling station with the blue flag of the Tory party and the orange flag of the Whigs.