Damascus Gate

| Damascus Gate | |

|---|---|

| |

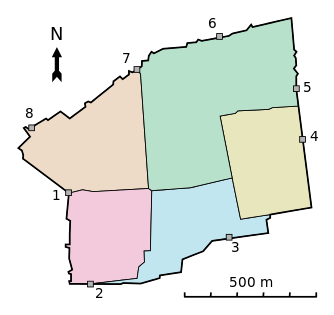

Location in Old Jerusalem | |

| General information | |

| Town or city | Jerusalem |

| Coordinates | 31°46′53.9″N 35°13′49.8″E / 31.781639°N 35.230500°E |

| Completed | 1537 |

Damascus Gate (Arabic: باب العامود, translit. Bab al-ʿAmud, Hebrew: שער שכם, Sha'ar Sh'khem) is one of the main entrances to the Old City of Jerusalem, Israel.[1] It is located in the wall on the city's northwest side where the highway leads out to Nablus, and from there, in times past, to the capital of Syria, Damascus; as such, its modern English name is Damascus Gate, and its modern Hebrew name, Sha'ar Shkhem (שער שכם), meaning Shechem Gate, or Nablus Gate.[1][2] Of its Arabic names, Bab al-Nasr (باب النصر) means "gate of victory," and Bab al-Amud (باب العامود) means "gate of the column."[1] The latter name, in use continuously since at least as early as the 10th century, preserves the memory of a design detail dating to the 2nd century AD Roman era gate.[1][3]

History

In its current form, the gate was built in 1537 under the rule of Suleiman the Magnificent, the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire.[1] Beneath the current gate, the remains of an earlier gate can be seen, dating back to at least the time of the Roman Emperor Hadrian in the 2nd century CE.[1] In front of this gate stood a Roman victory column topped with the Emperor Hadrian's image, as depicted on the 6th century Madaba Map.[1] This historical detail is preserved in the current gate's Arabic name, Bab el-Amud, meaning "gate of the column".[1] On the lintel to the 2nd century gate, under which one can pass today, is inscribed the city's name under Roman rule, Aelia Capitolina.[1] Hadrian had significantly expanded the gate which served as the main entrance to the city from at least as early as the 1st century CE during the rule of Agrippa I.[4] Josephus mentions in his Antiquities of the Jews that the third and outer wall of Jerusalem's Old City had been originally built by Agrippa I, in circa 37 CE – 41 CE.[5]

One of eight gates remade in the 10th century, Damascus Gate is the only one to have preserved the same name (i.e. Bab al-Amud) in modern times.[3] The Crusaders called it St. Stephen's Gate (in Latin, Porta Sancti Stephani), highlighting its proximity to the site of martyrdom of Saint Stephen, marked since the time of Empress Eudocia by a church and monastery.[2][6] Several phases of construction work on the gate took place the early Ayyubid period (1183-1192) and both early 12th century and later 13th century Crusader rule over Jerusalem.[2] A 1523 account of a visit to Jerusalem by a Jewish traveller from Leghorn uses the name Bâb el 'Amud and notes its proximity to the Cave of Zedekiah.[7]

Description

Damascus Gate is flanked by two towers, each equipped with machicolations. It is located at the edge of the Arab bazaar and marketplace in the Arab Quarter. In contrast to the Jaffa Gate, where stairs rise towards the gate, in the Damascus Gate, the stairs descend towards the gate. Until 1967, a crenellated turret loomed over the gate, but it was damaged in the fighting that took place in and around the Old City during the Six-Day War. In August 2011, Israel restored the turret, including its arrowslit, with the help of pictures from the early twentieth century when the British Empire controlled Jerusalem. Eleven anchors fasten the restored turret to the wall, and four stone slabs combine to form the crenellated top.[8]

Directly below the existing gate of Bab al-ʿAmud there is an older gate, believed to have been built in the early first or second centuries CE.[9][10] Such findings are in keeping with an account in the Midrash Rabba (Eikha Rabba 1:32) which states that Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai, during the Roman siege of Jerusalem, requested of Vespasian that he spare the western-most gates of the city (Hebrew: פילי מערבאה) that lead to Lydda (Lod). When the city was eventually taken, the Arab auxiliaries who had fought alongside the Romans under their general, Fanjar, also spared the wall from destruction. The chronicler who brings down the historical record adds: "And it was decreed in heaven that it should never be destroyed, seeing that the Divine Presence dwells in the West."

.jpg)

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 LaMar C. Berrett (1996). Discovering the World of the Bible (3rd ed.). Cedar Fort. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-910523-52-3.

- 1 2 3 Adrian J. Boas (2001). Jerusalem in the time of the crusades: society, landscape, and art in the Holy City under Frankish rule (Illustrated, reprint ed.). Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-415-23000-1.

- 1 2 David S Margoliouth (2010). Cairo, Jerusalem & Damascus: Three Chief Cities of the Egyptian Sultans. Walter S. S. Tyrwhitt, illustrator. Cosimo, Inc. p. 329. ISBN 978-1-61640-065-1.

- ↑ Amelia Thomas; Michael Kohn; Miriam Raphael; Dan Savery Raz (2010). Israel and the Palestinian Territories (6th, illustrated ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-74104-456-0.

- ↑ Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews) v.iv.§ 2

- ↑ fr:Basilique Saint-Étienne de Jérusalem

- ↑ Palestine Exploration Fund (1869). Quarterly statement, Issue 3. The Society. p. 376.

- ↑ Mazori, Dalia (16 August 2011). 'הכתר' של שער שכם בי-ם שוחזר מחדש ["The crown" of Damascus Gate in Jerusalem restored]. Nrg Maariv (in Hebrew). Retrieved 17 August 2011.

עתה, בתום עבודות שימור נרחבות, שוחזר הכתר והמבקרים יכולים ליהנות מיפי השער במלוא הדרו.

- ↑ Hillel Geva and Dan Bahat, Architectural and Chronological Aspects of the Ancient Damascus Gate Area, Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 48, No. 3/4, Jerusalem 1998, pp. 225-226

- ↑ Bahat, Dan (1998). "Architectural and Chronological Aspects of the Ancient Damascus Gate Area". Israel Exploration Journal. 48 (3/4): 223–235. Retrieved 25 May 2017 – via JSTOR. (Registration required (help)).

External links

- HD Virtual Tour of the Damascus Gate - December 2007

- Holy Land Photos:"Damascus Gate"

- Israel Antiquities Authority

Coordinates: 31°46′53.9″N 35°13′49.8″E / 31.781639°N 35.230500°E