Serbs of Croatia

|

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 186,633 (2011)[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Serbo-Croatian (Croatian and Serbian) | |

| Religion | |

| Serbian Orthodox Church |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Serbs |

|---|

|

|

Native communities |

|

Related people |

The Serbs of Croatia (Serbo-Croatian: Srbi u Hrvatskoj, Serbian Cyrillic: Срби у Хрватској) or Croatian Serbs (Хрватски Срби/Hrvatski Srbi) constitute the largest national minority in Croatia. The community is predominantly Eastern Orthodox Christian by religion, as opposed to the Croats who are Roman Catholic. There has been a substantial Serb population in the territory of what is today Croatia since the Early Modern period. Serbs settled in several migration waves, and they populated the Dalmatian hinterland, Lika, Kordun, Banija, Western Slavonia, Eastern Slavonia and Western Syrmia. An important part of their identity is the Habsburg military service, where Serbs defended the Military Frontier from the Ottoman Empire. The population has been declining sharply since 1991 and the Croatian War (1991–95), from 12% to 4%.

Overview

Traditional elements of their identity are the Orthodox faith, Cyrillic script and military history, while modern elements are language and literature, civic, social and political values, concern for ethnic status and national organisation, and celebration of the Liberation of Yugoslavia.[2]

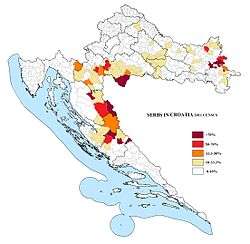

According to the 2011 census there were 186,633 ethnic Serbs living in Croatia, 4.4% of the total population. Their number was reduced by more than two thirds in the aftermath of the 1991–95 War in Croatia as the 1991 pre-war census had reported 581,663 Serbs living in Croatia, 12.2% of the total population.

Medieval history

According to De Administrando Imperio (960s), the Serbs settled in parts of modern-day Croatia during the rule of Heraclius (610–626) and soon formed a Serbian state which stretched across parts of modern-day Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Serbia. The lands of Pagania, Zachumlia and Travunia (which encompassed Dalmatia, roughly south of modern Split) were inhabited by Serbs.[3] According to the Royal Frankish Annals (821–822), Duke of Pannonia Ljudevit Posavski fled, during the Frankish invasion, from his seat in Sisak to the Serbs in western Bosnia, who controlled a great part of Dalmatia ("Sorabos, quae natio magnam Dalmatiae partem obtinere dicitur").[4][5] The event would have taken place during the rule of either Radoslav or his son, Prosigoj.[6] In the 880s, the Serb Prince Mutimir exiled his two brothers due to treachery, but kept his nephew Petar at the court. Petar later fled to the Croatian principality.[7] When Mutimir's son Pribislav had ruled for a year, Petar returned and defeated him, making him flee with his brothers Bran and Stefan to Croatia.[7] In 894 Bran returned but was defeated and blinded.[8] Pavle, the son of Bran, later returned and defeated Pavle with Bulgarian aid.[8]

King Mihailo I (1050–1081) built the St. Michael's Church in Ston, which has a fresco depicting him.[9]

Beloš Vukanović, a member of the Serb Vukanović dynasty, was given the title of Ban of Croatia by the Kingdom of Hungary and ruled 1142-1158 and briefly in 1163.[10]

In 1222, the King of Serbia Stefan Prvovenčani gifted Mljet, Babino Polje, the Saint Vid church on Korčula, Janin and Popova Luka and churches of St. Stephen and St. George, to a Benedictine monastery on Mljet.[11]

The first Serbian Orthodox monastery in Croatia, Krupa, was built in 1317 by Stephen Uroš II Milutin of Serbia, other medieval monuments include Krka (before 1345) and Dragović (late 14th century). Many monasteries and churches were damaged in the War in Croatia.[12] In 1333 the Republic of Ragusa bought the Pelješac peninsula and the coast land between Ston and Dubrovnik from Serbian King Stefan Dušan, the Ragusans promised freedom of religion to the Orthodox Serbs.[13]

Members of the Orlović Serb clan settled in Lika and Senj in 1432, they later joined the Uskoks.[14] On 22 November 1447, the Hungarian King Ladislaus V wrote a letter which mentioned "Rascians, who live in our cities of Medvedgrad, Rakovac, both Kalinik and in Koprivnica".[15]

After the Ottoman capture of Smederevo fortress in 1459, and by 1483, up to 200,000 Orthodox Christians moved into central Slavonia and Srijem (Syrmia in eastern Croatia).[16]

Early modern period

Muslim

Orthodox

Protestant

Mixed Catholic and Orthodox

Mixed Catholic and Protestant

As many former inhabitants of the Austrian-Ottoman borderland fled northwards or were captured by the Ottoman invaders, they left unpopulated areas.[17] At the beginning of the 16th century settlements of Orthodox Christians were also established in western Croatia.[18] In the first half of the 16th century Serbs settled Ottoman part of Slavonia while in the second part of the 16th century they moved to Austrian part of Slavonia.[19] In 1550 they established the Lepavina Monastery.[20] The Austrian Empire encouraged people from the Ottoman Empire to settle as free peasant soldiers, establishing the Military Frontiers (Militärgrenze) in 1522 (hence they were known as Grenzers, Krajišnici).[21] They were mostly of Orthodox faith, Serbs and Vlachs (Romance-speaking).[17] Catholic Vlachs were assimilated into Croats, while the Orthodox, under the Serbian Orthodox Church, identified with Serbs.[22][23] The militarized frontier would serve as a buffer against Ottoman incursions.[21] The Military frontiers had territory of modern Croatia, Serbia, Romania and Hungary. The colonists were granted small tracts of land, exempted from some obligations, and were to retain a share of all war booty.[21] The Grenzers elected their own captains (vojvode) and magistrates (knezovi). All Orthodox settlers were promised freedom of worship.[17][24] By 1538, the Croatian and Slavonian Military Frontier were established.[21] Serbs acted as the cordon sanitaire against Turkish incursions from the Ottoman Empire.[25] The Military frontiers are virtually identical to the present Serbian settlements (war-time Republic of Serbian Krajina).[26]

In 1593, Provveditore Generale Cristoforo Valier mentions three nations constituting the Uskoks: "natives of Senj, Croatians, and Morlachs from the Turkish parts".[27] Many of the Uskoks, who fought a guerrilla war with the Ottoman Empire were Serbs (Orthodox Christians), who fled from Ottoman Turkish rule and settled in White Carniola and Zumberak.[28][29][30][31] A letter of Emperor Ferdinand, sent on November 6, 1538, to Croatian ban Petar Keglević, in which he wrote "Captains and dukes of the Rasians, or the Serbs, or the Vlachs, who are commonly called the Serbs".[32] Tihomir Đorđević points to the already known fact that the name 'Vlach' didn't only refer to genuine Vlachs or Serbs but also to cattle breeders in general.[32]

In the Venetian documents from the late 16th and 17th centuries, the name "Morlachs" (another term of Vlachs, first mentioned in the 14th century) was used for immigrants from conquered territory previously of Croatian and Bosnian kingdoms by the Ottoman Empire. They were of both Orthodox and Catholic faith, settled inland of the coastal cities of Dalmatia, and entered the military service of both Venice and Ottoman Empire.[33]

Right: Josip Runjanin, composer of Croatian national anthem

There was a Serb population movement from the Ottoman territories into Venetian Dalmatia in this period. The Venetian government welcomed immigrants, as they protected possessions against the Ottomans. The Morlachs, former Ottoman subjects, helped Venice triple its size in Dalmatia. Serb (Orthodox) refugees are mentioned in 1654 by the bishop of Nin, similarly by the bishop of Makarska, in 1658 by the archbishop of Zadar. Major population movements into Venetian Dalmatia occurred during the 1670s and 1680s. In the summer of 1685, Cosmi, the Archbishop of Split, wrote that Morlach leader Stojan Janković had brought 300 families with him to Dalmatia, and also that around Trogir and Split there were 5,000 refugees from Ottoman lands, without food; this was seen as a serious threat to the defense of Dalmatia. Grain sent by the Pope proved insufficient, and these were forced to launch expeditions into Ottoman territory.[34]

The military border was returned in 1881 to the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia. In 1918, it became part of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, which immediately joined the Kingdom of Serbia to form the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Contemporary period

World War II

Following the Invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941 the Axis powers occupied the entire territory of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. On the territory of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia a puppet state called the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was created, led by the Ustaše, a Croatian fascist movement.

The Ustaše government saw Serbs as a "disruptive element" and it immediately embarked on a program of ethnic cleansing and genocide. They went on to create concentration camps in which Serbs, Jews, Gypsies, anti-fascist Croats and Bosniaks perished in large numbers, the most notorious of which was the Jasenovac concentration camp. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum between 320,000 and 340,000 Serbs were killed by the Ustaše or their allies during World War II.

The main paramilitary force that the Serbs of Croatia were involved with was the Yugoslav Partisans who were particularly strong in the regions of Lika, Kordun and Banija, they were connected with Partisans in Bosanska Krajina, they were the main recruiting ground for the Yugoslav Partisans besides Serbia and Montenegro due to the genocide and the ethnic cleansing that the Independent State of Croatia was conducting against the civilian Serb population. Because of this some of the main operations, battles and free territories were in the areas populated by Serbs in Bosnian Kraina and adjacent areas. In Dalmatia the main resistance movement was the Chetniks. In March 1942 the Chetniks formed the Dinara Division, led by Orthodox priest Momčilo Đujić. This unit had a program to defend Serb population from the Ustaše led genocide, with arms and political activity. During the war, this division was involved in ethnic cleansing of this area.[35] Chetniks in Croatia collaborated with fascist Italy to achieve their goals of protecting Serb civilians from genocide, in return they guaranteed Italians safety and defended them from the Partisans.[35] Estimation of the priest Momčilo Đujić was that they saved as many as 500 000 Serbs in Dalmatia, Lika and Bosanska Krajina.

Socialist Yugoslavia

During the Second World War, at the Second and Third sessions of the National Anti-Fascist Council of the Peoples Liberation of Croatia (ZAVNOH) held in October 1943 and May 1944 respectively, the equality of the Serbian and Croatian nations, as constituent nations of the federal unit of Croatia, was recognized in every aspect.[36] Later, in 1963, the Croatian Constitution did not mention the Serbs in Croatia as constituent nation of SR Croatia, but with the Constitutional amendments of 1971 this was now explicitly done in order to guarantee the rights of the Serbs in Croatia. This formulation implied that Croatia was not the national state of the Croats, but stated that Croatia was the land of Croats and Serbs.[37] Then, on 22 December 1990, HDZ government of Franjo Tuđman promulgated a new Croatian constitution that changed the wording with regard to Serbs of Croatia. In the first paragraph of the Article 12, Croatian was specified as the official language and alphabet, and dual-language road signs were torn down even in Serb majority areas.[38] Furthermore, a number of Serbs were removed from the bureaucracies and the police and replaced by ethnic Croats.[38] Many Serbs in government lost their jobs, and HDZ made themselves target of Serbian propaganda by having party members attempting to rehabilitate the WWII Croatian fascist movement Ustaše, or by saying that the numbers of people killed in Jasenovac concentration camp were inflated.[39] The party representing the interests of Serbs in Croatia, the Serbian Democratic Party (SDS), which rejected the new constitution,[38] began building its own national governmental entity in order to preserve rights that Serbs saw as being stripped away and to enhance the sovereignty of the Croatian Serbs.[40]

War in Croatia

Amid political changes during the breakup of Yugoslavia and following the Croatian Democratic Union's victory in the 1990 general election, the Croatian Parliament ratified a new constitution in December 1990 where Serbs were listed with other nations and minorities.[41][42][43][44][45] On a practical level, it became obvious that jobs, property rights, and even residence status depended on having Croatian citizenship, which was not an automatic right for non-Croats.[46]

The percentage of those declaring themselves as Serbs, according to the 1991 census, was 12.2% (78.1% of the population declared itself to be Croat). Although today Serbs are able to return to Croatia, in reality a majority of Serbs who left during organized evacuation[47] (citing:[48][49][50] see section "Literature")[51] in 1995 choose to remain citizens of other countries in which they gained citizenship. Consequently, today Serbs constitute 4% of Croatian population, down from the prewar population of 12%.

Before the Croatian War of Independence, part of the Croatian Serbs rebelled ("balvan revolucija") and led a military campaign against the Croatian state, creating an unrecognized state called Republic of Serbian Krajina in hopes of achieving independence, international recognition, and complete self-governance from the government of Croatia. The rebellion was incited from Serbia. As the popularity of the unification of Serbian people into a Greater Serbia with Serbia proper increased, the rebellion against the Croatian rule also increased. While some Serb politicians from Croatia sought a peaceful solution, others organized Serb parties in the Croatian government-controlled areas, like Milan Đukić; some of them (Veljko Džakula) unsuccessfully tried to organize the parties in the rebelled areas, but their work was prevented by Serb warmongers.[52]

The Republic of Krajina had de facto control over one third of Croatian territory during its existence between 1991 and 1995 but failed to gain international recognition.

The war ended with a military success in Operation Storm in 1995 and subsequent peaceful reintegration of the remaining renegade territory in eastern Slavonia in 1998 as a result of the signed Erdut Agreement from 1995. Local Serbs are, on the ground that Agreement, established the Serb National Council and gained the right to establish the Joint Council of Municipalities.

Right: Croatian soldier destroying sign of Saint Sava street

In February 2015, during the Croatia–Serbia genocide case, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) dismissed the Serbian lawsuit claim that Operation Storm constituted genocide,[53] ruling that Croatia did not have the specific intent to exterminate the country's Serb minority, though it reaffirmed that serious crimes against Serb civilians had taken place.[53][54] The judgment stated that it is not disputed that a substantial part of the Serb population fled that region as a direct consequence of the military actions. The Croatian authorities were aware that the operation would provoke a mass exodus; they even to some extent predicated their military planning on such an exodus, which they considered not only probable, but desirable.[55] Fleeing civilians and people remaining in United Nations protected areas were subject to various forms of harassment, including military assaults and acts by Croatian civilians. On 8 August, a refugee column was shelled.[56]

Although it was very difficult to determine the number of properties destroyed during and after Operation Storm since a large number of houses sustained some degree of damage since the beginning of the war, Human Rights Watch (HRW) estimated that more than 5,000 houses were destroyed in the area during and after the battle.[57] Out of the 122 Serbian Orthodox churches in the area, one was destroyed and 17 were damaged. HRW also reported that the vast majority of the abuses were committed by Croatian forces. These abuses, which continued on a large scale even months after Operation Storm, included summary executions of elderly and infirm Serbs who remained behind and the wholesale burning and destruction of Serbian villages and property. In the months following the August offensive, at least 150 Serb civilians were summarily executed and another 110 persons forcibly disappeared.[58] One example of such crimes was the Varivode massacre, where nine elderly Serb villagers were killed by the Croatian Army.[59]

At the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia at The Hague, Milan Babić was indicted, pleaded guilty and was convicted for "persecutions on political, racial and religious grounds, a crime against humanity".[60][61] Babić stated during his trial that "during the events, and in particular at the beginning of his political career, he was strongly influenced and misled by Serbian propaganda".[62]

A small minority of pre-war Serb population have returned to Croatia. Today, the majority of the pre-war Serb population from Croatia settled in Serbia and Republika Srpska.[63] After Croatian and other Yugoslav Wars, Serbia became home to highest number of refugees (including Croatian Serbs) and IDPs in Europe.[64][65][66]

Modern Croatia

Tension and violence between Serbs and Croats has reduced since 2000 and has remained low to this day, however, significant problems remain.[67] The main issue is high-level official and social discrimination against the Serbs.[68]

At the height levels of the government, new laws are continuously being introduced in order to combat this discrimination, thus, demonstrating an effort on the part of government.[67] For example, lengthy and in some cases unfair proceedings,[67] particularly in lower level courts, remain a major problem for Serbian returnees pursuing their rights in court.[67] In addition, Serbs continue to be discriminated against in access to employment and in realizing other economic and social rights.[69] Also some cases of violence and harassment against Croatian Serbs continue to be reported.[67]

The property laws allegedly favor Bosnian Croats refugees who took residence in houses that were left unoccupied and unguarded by Serbs after Operation Storm.[67] Amnesty International's 2005 report considers one of the greatest obstacles to the return of thousands of Croatian Serbs has been the failure of the Croatian authorities to provide adequate housing solutions to Croatian Serbs who were stripped of their occupancy rights, including where possible by reinstating occupancy rights to those who had been affected by their discriminatory termination.[67]

The European Court of Human Rights decided against Croatian Serb Kristina Blečić, stripped her of occupancy rights after leaving her house in 1991 in Zadar.[70] In 2009, the UN Human Rights Committee found a wartime termination of occupancy rights of a Serbian family to violate ICCPR.[71] In 2010, the European Committee on Social Rights found the treatment of Serbs in Croatia in respect of housing to be discriminatory and too slow, thus in violation of Croatia's obligations under the European Social Charter.[72]

In 2015 Amnesty International reported that Croatian Serbs continued to face discrimination in public sector employment and the restitution of tenancy rights to social housing vacated during the war.[73] In 2017 they again pointed Serbs faced significant barriers to employment and obstacles to regain their property. Amnesty International also said that right to use minority languages and script continued to be politicized and unimplemented in some towns and thar heightened nationalist rhetoric and hate speech contributed to growing ethnic intolerance and insecurity.[74]

Demographics

According to the 2011 census there were 186,633 ethnic Serbs living in Croatia, 4.4% of the total population. Their number was reduced by more than two thirds in the aftermath of the 1991–95 War in Croatia as the 1991 pre-war census had reported 581,663 Serbs living in Croatia, 12.2% of the total population.

| Year | Serbs | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1900[76] | 548,302 | 17.35% |

| 1910[76] | 564,214 | 16.60% |

| 1921[76] | 584,058 | 16.94% |

| 1931[76] | 636,518 | 16.81% |

| 1948[77] | 543,795 | 14.47% |

| 1953[78] | 588,411 | 15.01% |

| 1961[79] | 624,956 | 15.02% |

| 1971[76] | 626,789 | 14.16% |

| 1981[76] | 531,502 | 11.55% |

| 1991[76] | 581,663 | 12.16% |

| 2001 | 201,631 | 4.54% |

| 2011 | 186,633 | 4.36% |

Counties

Counties with significant Serb minority (10% or more):[80]

| County | Serbs | % |

|---|---|---|

| Vukovar-Srijem County | 27,824 | 15.50% |

| Lika-Senj County | 6,949 | 13.65% |

| Sisak-Moslavina County | 21,002 | 12.18% |

| Šibenik-Knin County | 11,518 | 10.53% |

| Karlovac County | 13,408 | 10.40% |

Cities

Cities with significant Serb minority (10% or more):

- Vrbovsko (1,788 or 35.22%)

- Vukovar (9,654 or 34.87%)

- Obrovac (1,359 or 31.44%)

- Glina (2,549 or 27.46%)

- Beli Manastir (2,572 or 25.55%)

- Hrvatska Kostajnica (690 or 25.04%)

- Knin (3,551 or 23.05%)

- Skradin (679 or 17.75%)

- Ogulin (2,466 or 17.72%)

- Pakrac (1,340 or 15.84%)

- Lipik (860 or 13.94%)

- Benkovac (1,519 or 13.78%)

- Daruvar (1,429 or 12.28%)

- Petrinja (2,710 or 10.98%)

- Slunj (534 or 10.52%)

- Garešnica (1,062 or 10.14%)

Municipalities

Municipalities with significant Serb population (10% or more):

- Ervenik (1,074 or 97.19%)

- Negoslavci (1,417 or 96.86%)

- Markušica (2,302 or 90.10%)

- Trpinja (5,001 or 89.75%)

- Borovo (4,537 or 89.73%)

- Biskupija (1,452 or 85.46%)

- Šodolovci (1,365 or 82.58%)

- Donji Lapac (1,704 or 80.64%)

- Vrhovine (1,108 or 80.23%)

- Civljane (188 or 78.66%)

- Dvor (4,005 or 71.90%)

- Krnjak (1,362 or 68.61%)

- Vrginmost (1,976 or 66.53%)

- Jagodnjak (1,333 or 65.89%)

- Kistanje (2,166 or 62.22%)

- Erdut (3,987 or 54.56%)

- Udbina (958 or 51.12%)

- Plaški (952 or 45.55%)

- Gračac (2,118 or 45.16%)

- Vojnić (2,130 or 44.71%)

- Donji Kukuruzari (569 or 34.82%)

- Topusko (893 or 29.92%)

- Majur (323 or 27.26%)

- Plitvička Jezera (1,184 or 27.08%)

- Darda (1,603 or 23.20%)

- Sunja (1,280 or 22.27%)

- Stari Jankovci (952 or 21.61%)

- Saborsko (136 or 21.52%)

- Okučani (716 or 20.77%)

- Dragalić (243 or 17.85%)

- Kneževi Vinogradi (815 or 17.66%)

- Popovac (355 or 17.03%)

- Viljevo (340 or 16.46%)

- Rasinja (533 or 16.31%)

- Podgorač (466 or 16.20%)

- Lovinac (162 or 16.09%)

- Stara Gradiška (197 or 14.45%)

- Nova Bukovica (245 or 13.83%)

- Sirač (300 or 13.53%)

- Đulovac (427 or 13.16%)

- Velika Pisanica (231 or 12.97%)

- Sokolovac (440 or 12.88%)

- Levanjska Varoš (153 or 12.81%)

- Lišane Ostrovičke (87 or 12.46%)

- Barilovići (354 or 11.84%)

- Lasinja (192 or 11.82%)

- Dežanovac (318 or 11.71%)

- Suhopolje (763 or 11.42%)

- Nijemci (515 or 10.95%)

- Tompojevci (164 or 10.48%)

- Polača (153 or 10.42%)

- Magadenovac (195 or 10.07%)

Culture

Serbs in Croatia have cultural traditions ranging from kolo dances and singing, which are kept alive today by performances by various folklore groups. Notable traditions include gusle, Ojkanje singing, Čuvari Hristovog groba.

Religion

Serbs of Croatia are Serbian Orthodox. There are many Orthodox monasteries across Croatia, built since the 14th century. Most notable and historically significant are the Krka monastery, Krupa monastery, Dragović monastery, Lepavina Monastery and Gomirje monastery. Many Orthodox churches were demolished during World War II and Yugoslav war, while some were rebuilt by the EU funding, Croatian government and Serbian diaspora donations.[81]

In the 1560s a Serbian Orthodox bishop was installed in the Metropolitanate of Požega, seated in the monastery of Remeta.[82] In the 17th century, the Eparchy of Marča was founded at Marča, in the Croatian frontier.[82] These were part of the Serbian Orthodox Patriarchate of Peć, which was reestablished in 1557, and lasted under Ottoman governance until 1766.[82] Other bishoprics were founded, although their approval by the Habsburgs hinged on the belief that they would facilitate the union of these Orthodox Christians with the Catholic Church, and in fact, many, including some Orthodox bishops, did unify with Rome.[82]

Serbs in the Croatian Military Frontier were out of the jurisdiction of the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć and in 1611, and after demands from the community, the Pope established the Eparchy of Marča (Vratanija) with seat at the Serbian-built Marča Monastery, with a Byzantine vicar instated as bishop sub-ordinate to the Roman Catholic bishop of Zagreb - working to bring Serbian Orthodox Christians into communion with Rome, which caused struggle of power between the Catholics and the Serbs over the region.[30][31]

In 1695 Orthodox Eparchy of Lika-Krbava and Zrinopolje was established by metropolitan Atanasije Ljubojević and certified by Emperor Josef I in 1707. In 1735 the Serbian Orthodox protested in the Marča Monastery and became part of the Serbian Orthodox Church until 1753 when the Pope restored the Roman Catholic clergy. On June 17, 1777 the Eparchy of Križevci was permanently established by Pope Pius VI with its Episcopal see at Križevci, near Zagreb, thus forming the Croatian Greek Catholic Church which would after World War I include other people; the Rusyns and ethnic Ukrainians of Yugoslavia.[30][31]

Jovan, the Metropolitan of Zagreb and Ljubljana, stated that c. 30,000 Serbs had converted to Catholicism since the Operation Oluja (1995).[83] In the 2011 census, regarding religious affiliation, c. 40,000 declared as "Serbs of the Orthodox faith", while 160,000 declared as "Orthodox".[83]

Language

Serbian language is officially used in 23 cities and municipalities in Croatia.[84]

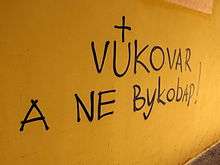

Right: Graffiti during anti-Cyrillic protests

In April 2015 United Nations Human Rights Committee has urged Croatia to ensure the right of minorities to use their language and alphabet.[85] Committee report stated that particularly concerns the use of Serbian Cyrillic in the town of Vukovar and municipalities concerned.[85] Serbian Foreign Minister Ivica Dačić said that his country welcomes the UN Human Rights Committee's report.[86]

Although 2011 census puts Serbs as the largest national minority in Croatia with 4.4% of the total population, the number of people who had declared Serbian language as their native is 52,879 (1.23% of the total population).[87]

Politics

Serbs are officially recognized as an autochthonous national minority, and as such, they elect three representatives to the Croatian Parliament.[88]

The major Serb party in Croatia is the Independent Democratic Serb Party (SDSS). In the elections of 2007 and 2011, the SDSS has won all 3 Serbian seats in the parliament. In the Cabinet of Ivo Sanader II, the party was part of the ruling coalition led by the conservative Croatian Democratic Union, and SDSS member Slobodan Uzelac held the post of Deputy Prime Minister.

There are also ethnic Serb politicians who are members of mainstream political parties, such as the centre-left Social Democratic Party's MPs and Milanović cabinet members Željko Jovanović, Branko Grčić and Milanka Opačić.

Community in Serbia

Some 250,000 Serbs were resettled in Serbia during and after the Croatian War, of which the larger part took Serbian citizenship.[89] In 2011, there were 284,334 Serbs from Croatia living in Serbia (without Kosovo). The majority lived in Vojvodina (127,884), then in Central and South Serbia (114,434). In 2013, ca. 45,000 from Croatia still had refugee status in Serbia.[89][90]

Notable people

Artists

- Arsen Dedić, chanson singer

- Milan Mladenović (1958-1994) - musician best known as the frontman of the Yugoslav art rock band Ekatarina Velika

- Medo Pucic (1821-1882) - writer and politician

- Vladan Desnica (1905–1967) - writer

- Vojin Jelić (1921–2004) - poet

- Simo Matavulj (1852–1908) - novelist

- Lukijan Mušicki (1777–1837) - notable Baroque poet, writer and polyglot[91]

- Zaharije Orfelin (1726–1785) - 18th-century polymath[92]

- Božidar Petranović (1809–1874) - author, scholar, and journalist[93]

- Petar Preradović (1818–1872) - poet and Austrian general[94]

- Josif Runjanin (1821–1878) - composer of the Croatian national anthem[95]

- Rade Šerbedžija (born 1946) - film actor[96]

- Petar Kralj (1941–2011), Serbian actor

- Slavko Štimac (born 1960), Serbian actor

- Bogdan Diklić (born 1953), Serbian actor

- Nives Celsius (born 1981) - Croatian socialite, model, singer and writer

- Konstantin Vojnović (1832–1903) politician, university professor and rector of the University of Zagreb

- Ivo Vojnović (1857–1929) - writer[97]

- Matija Ban (1818-1903) - poet, playwright

- Sava Šumanović (1896–1942), Serbian painter

Scientists

- Nikodim Milaš (1845–1915) - bishop and perhaps the greatest Serbian expert on church law

- Nikola Tesla (1856–1943) - inventor, mechanical engineer, and electrical engineer

- Milutin Milanković (1879–1958) - geophysicist and civil engineer, best known for his theory of ice ages

- Jovan Karamata (1902–1967) - mathematician

- Mihailo Merćep (1864–1937) - notable cyclist and aviation pioneer

- Sima Ćirković (1929–2009) - historian

- Dejan Medaković (1922–2008) - historian and writer winner of the Herder Prize

- Sava Mrkalj (1783–1833) - linguist and poet

- Gajo Petrović (1927–1993) - philosopher

- Nikola Hajdin (1923) - construction engineer and President of SANU

Athletes

- Siniša Mihajlović (born 1969) - Serbian football manager and former player, European Cup champion

- Vladimir Beara (1928-2014) - football player and manager, Olympic silver medalist

- Ilija Petković (bron 1945) - football player and manager

- Robert Prosinečki (bron 1969) - Croatian football player and manager, born to a Croat father and a Serb mother, World Cup bronze medalist

- Dragan Andrić (born 1962) - Serbian water polo player, two-time Olympic champion

- Vladimir Vujasinović (born 1987) - Serbian water polo player and manager, three-time Olympic medalist, World and European champion

- Danijel Ljuboja (born 1978) - Serbian football player

- Ivan Ergić (born 1981) - Serbian football player

- Dražen Petrović, (1964 – 1993) - Croatian basketball player, born to a Serb father and a Croat mother, World and European champion

- Predrag Stojaković (born 1977) - Serbian basketball player,[98] World, European and NBA champion

- Duško Savanović (born 1983) - Serbian basketball player

- Zoran Erceg (born 1985) - Serbian basketball player

- Kosta Perović (born 1985), Serbian basketballer player, Eurobasket silver medalist

- Sava Lešić (born 1988) - Serbian basketball player

- Milan Mačvan (born 1989) - Serbian basketball player, Olympic and Eurobasket silver medalist

- Nemanja Bezbradica (born 1993) - Serbian basketball player, 3x3 Youth Olympic champion

- Ognjen Dobrić (born 1994) - Serbian basketball player

- Aleks Marić (born 1984) - Australian basketball player

- Božidar Maljković, Serbian basketball coach, four-time Euroleague champion, former player

- Nenad Čanak - Serbian basketball player and manager

- Jasna Šekarić (born 1965) - Serbian sports shooter, five-time Olympic medalist, World and European champion[99]

- Damir Mikec, Serbian sports shooter, European Games chanpion

- Miloš Milošević, former Croatian swimmer, World and European champion

- Andrija Prlainović (born 1987) - Serbian water polo player, Olympic, World and European champion

- Svetlana Ognjenović (born 1981), Serbian handball player, World Championship silver medalist

- Jelena Popović (born 1984), Serbian handball player, World Championship silver medalist

- Jelena Dokic (born 1983) - tennis player, born to a Serb father and a Croat mother, former World No.4

- Tanja Dragić (born 1991) - Serbian Paralympian athlete, Paralympic and World champion

- Ljubomir Vračarević (1947 – 2013), Serbian martial artist and founder of Real Aikido

Other

- Jelena Nemanjić Šubić (14th century) - founder of Krka monastery

- Beloš Vukanović (1110–1198) - Serbian prince, Ban of Croatia between 1142 and 1163

- Gerasim Zelić (1752–1838)- Serbian Orthodox archimandrite, traveler, and writer

- Svetozar Boroević (1856–1920) - Austro-Hungarian Field Marshal

- Momčilo Đujić (1907–1999) - Commander in the WWII Chetnik movement

- Stevan Šupljikac (1786–1848) was a voivode (military commander) and the first Duke of the Serbian Vojvodina

- Stjepan Jovanović (1828–1885) - notable military commander of Austrian Empire

- Rade Končar (1911–1942) - communist leader and legendary WWII resistance fighter

- Boško Buha (1926–1943) - WWII resistance fighter

- Serbian Patriarch Pavle (1914–2009) (born Gojko Stojčević) - former Serbian Patriarch[100]

- Svetozar Pribićević (1875–1936) - early 20th-century politician in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia[101]

- Toma Rosandić (1878–1958), Serbian sculptor, born in Split

- Jovan Rašković (1929–1992) - politician who first called for a Serbian autonomy within Croatia in the 1990s

- Slavko Ćuruvija (1949–1999) - a journalist and newspaper publisher

- Josif Rajačić (1785–1861), metropolitan of Sremski Karlovci, Serbian patriarch, administrator of Serbian Vojvodina and baron[102]

- Jovo Stanisavljević Čaruga (1897–1925) - legendary outlaw in early 20th-century Slavonia

- Mirko Marjanović (1937–2006), a former Prime Minister of Serbia and a high-ranking official in Slobodan Milošević's Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS)

- Nada Dimić (1923-1942), Yugoslav communist and People's Hero of Yugoslavia

- Milan Babić (1956–2006), first president of Serbian Krajina, convicted war criminal

See also

- Serbs of Zagreb

- Serbs in Dubrovnik

- Serbs of Vukovar

- Serb National Council, elected body acting as a form of self-government and institution of cultural autonomy

- Joint Council of Municipalities

- Independent Democratic Serb Party

- Republic of Serbian Krajina

- Prosvjeta, Croatian Serb Cultural Society

- Serbian Orthodox Secondary School in Zagreb

- Novosti (Croatia)

- Radio Borovo

References

- ↑ "3. Stanovništvo prema narodnosti, popisi 1971. – 2011.". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- ↑ "Srbi u Hrvatskoj zabrinuti da će nestati".

- ↑ Fine (1994), 53

- ↑ Serbian Studies. 2–3. North American Society for Serbian Studies. 1982. p. 29.

- ↑ Eginhard (1711). Eginhartus de vita et gestis Caroli Magni. ex Officina Guilielmi Vande Water. p. 192.

- ↑ Ćirković 2004, p. 14.

- 1 2 The early medieval Balkans, p. 141

- 1 2 The early medieval Balkans, p. 150

- ↑ Pavle Ivić (1995). The history of Serbian culture. Porthill Publishers. p. 101.

- ↑ Dr. M. Wertner, "Ungarns Palatine und Bane im Zeit-alter der Arpaden" (Ungarische Revue, 14, 1894, 129—177)

- ↑ Diplomatički zbornik kraljevine Hrvatske, Dalmacije i Slavonije. 3. Zavod za povijesne znanosti JAZU. 1905. p. 480.

Stephanus rex Serviae monasterio St. Mariae in insula Mljet donat pagos quosdam [...] 1222, kralj srpski Stefan Prvovjenčani dava benediktinskome manastiru na Mljetu cio Mljet i Babino Polje, i na Korčuli crkvu sv. Vida, pa Janinu s Popovom Lukom i crkve sv. Stjepana i sv. Gjurgja, a u Stonu crkvu sv. [...]

- ↑ Mitja Velikonja (5 February 2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

- ↑ Fine (1994), p. 286

- ↑ Јован Ердељановић (1930). О Пореклу Буњеваца.

- ↑ "Rascianos in castris nostris Medwe, Rakonok, utriusque Kemlek et Caproncza constitutis"

- ↑ (Frucht 2005, p. 535): "Population movements began in earnest after the Battle of Smederevo in 1459, and by 1483, up to two hundred thousand Orthodox Christians had moved into central Slavonia and Srijem (eastern Croatia)."

- 1 2 3 Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945: occupation and collaboration. Board of Trustees of Leland Stanford Junior University. p. 390. ISBN 0-8047-3615-4.

- ↑ (Frucht 2005, p. 535): "In the early sixteenth century Orthodox populations had also been established in western Croatia."

- ↑ sinod, Srpska pravoslavna crkva. Sveti arhijerejski (1972). Službeni list Srpske pravoslavne crkve. p. 55.

Тридесетих година XVI в. многи Срби из Босне су се населили у Крањској, Штајерској и Жумберку. ... Сеобе Срба у Славонију и Хрватску трајале су кроз цео XVI, XVII и XVIII в. У првој половини XVI в. су се најпре засељавали у турском делу Славоније, а у другој половини истог века су се пресељавали из турског у аустријски део Славони- је.

- ↑ sinod, Srpska pravoslavna crkva. Sveti arhijerejski (2007). Glasnik. 89. p. 290.

МАНАСТИР ЛЕПАВИНА, посвећен Ваведењу Пресвете Богородице, подигнут 1550.

- 1 2 3 4 Ramet, p. 82

- ↑ Banac, Ivo (1984). The national question in Yugoslavia: origins, history, politics. Cornell University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-8014-1675-2.

- ↑ Bues, Almut (2005). Zones of fracture in modern Europe: the Baltic countries, the Balkans, and Notrhen Italy. Harassowitz Verlag. p. 101. ISBN 3-447-05119-1.

- ↑ Sabrina P. Ramet, "Whose democracy?: nationalism, religion, and the doctrine of collective rights in post-1989 Eastern Europe", Rowman & Littlefield, 1997, ISBN 0-8476-8324-9, p. 83

- ↑ William Safran, The secular and the sacred: nation, religion, and politics, p. 169

- ↑ Nicholas J. Miller, 1998, Between Nation and State: Serbian Politics in Croatia Before the First World War, p. 10

- ↑ Fine (2006), p. 218

- ↑ Europe:A History by Norman Davies (1996), p. 561.

- ↑ Goffman (2002), p. 190.

- 1 2 3 https://books.google.com/books?id=ovCVDLYN_JgC

- 1 2 3 https://books.google.com/books?id=0pmkrY29qkIC%5B%5D

- 1 2 Gavrilović, Danijela, "Elements of Ethnic Identification of the Serbs" from FACTA UNIVERSITATIS - Series Philosophy, Sociology, Psychology and History (10/2003), pp. 717-730

- ↑ Croatian Encyclopaedia (2011). "Morlaci" (in Croatian).

- ↑ Živojinović, Dragan R. (1989). Ninić, Ivan, ed. "Wars, population migrations and religious proselytism in Dalmatia during the second half of the XVIIth century". Migrations in Balkan History: 77–82.

- 1 2 Tomasevich 1975, p. 171.

- ↑ Yugoslavia Through Documents: From Its Creation to Its Dissolution edited by Snežana Trifunovska, page 477, it says: "at the Second and Third sessions of the National Anti-Fascist Council of the Peoples Liberation of Croatia (ZAVNOH),...,the equality of the Serbs and the Croats, as constituent peoples of the federal unit of Croatia, were recognized in every respect."

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of Croatia by Robert Stallaerts, page 53, regarding the 1971 constitutional amendments says: "It stated that Croatia was the state of Croats and Serbs."

- 1 2 3 Living Together After Ethnic Killing: Exploring the Chaim Kaufman Argument by Roy Licklider and Mia Bloom, page 158, says: Previously, a constituent nation in the Republic of Croatia, ..."

- ↑ Croatia by Piers Letcher, page 20, it says: "The HDZ also put Crotias 600,000 Serbs on the defensive by changing their status from "constituent nation" in Croatia, to "national minority" and many Serbs in government lost their jobs."

- ↑ Words Over War: Mediation and Arbitration to Prevent Deadly Conflict by Melanie Greenberg, John H. Barton and Margaret E. McGuinness, at page 83, says: "The new Croatian constitution ... renounced the hitherto protected status of ethnic Serbs as a separate constituent nation embedded in the old constitution,... In response, the SDS in Krajina begin building its own national governamental entity in order to preserve the rights that had been stripped away and to enhance the sovereignty of Croatian Serbs.

- ↑ (in Croatian) Dunja Bonacci Skenderović i Mario Jareb: Hrvatski nacionalni simboli između stereotipa i istine, Časopis za suvremenu povijest, y. 36, br. 2, p. 731.-760., 2004

- ↑ Yugoslavia Through Documents: From Its Creation to Its Dissolution edited by Snežana Trifunovska, page 477

- ↑ Integration and Stabilization: A Monetary View by George Macesich, page 24

- ↑ The Quality of Government by Bo Rothstein, page 89

- ↑ Soft Borders by Julie Mostov, page 67

- ↑ David Bruce Macdonald (13 February 2003). Balkan Holocausts?: Serbian and Croatian Victim Centred Propaganda and the War in Yugoslavia. Manchester University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-84779-570-0.

His 1990 Constitution, for example, conspicuously omitted Serbs as a constituent nation within the new country. [...] On practical level, it became obvious that jobs, property rights, and even residence status depended on having Croatian citizenship, whiich was not an automatic right for non-Croats

- ↑ Barić, Nikica: Srpska pobuna u Hrvatskoj 1990.-1995., Golden marketing. Tehnička knjiga, Zagreb, 2005

- ↑ Drago Kovačević, "Kavez - Krajina u dogovorenom ratu", Beograd 2003., p. 93.-94

- ↑ Milisav Sekulić, "Knin je pao u Beogradu", Bad Vilbel 2001., p. 171.-246., p. 179

- ↑ Marko Vrcelj, "Rat za Srpsku Krajinu 1991-95", Beograd 2002., p. 212.-222.

- ↑ 13 mei 2007. "RSK Evacuation Practise one month before Operation Storm". Nl.youtube.com. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ (in Croatian) Croatian Iuridic Portal Đakula prvi svjedočio protiv Martića

- 1 2 BBC News & 3 February 2015

- ↑ ICJ & 3 February 2015, pp. 4, 141, 142

- ↑ ICJ & 3 February 2015, p. 131

- ↑ ICJ & 3 February 2015, pp. 4, 132, 133

- ↑ HRW 1996, p. 19

- ↑ HRW 1996

- ↑ Neomedia Komunikacije. "Vrhovni sud: Hrvatska je odgovorna za zločin u Varivodama!".

- ↑ ICTY (2004). "Judgement in the Case the Prosecutor v. Milan Babic". Archived from the original on 2007-07-17. Retrieved 2006-03-07.

- ↑ ICTY (6 November 2003). "Indictment" (PDF). Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ "Sentencing judgement" (PDF). 29 June 2004. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ "Croatia: Operation "Storm" - still no justice ten years on". Amnesty International. 2005-08-04. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- ↑ "Serbia home to highest number of refugees and IDPs in Europe". B92. 20 June 2010.

- ↑ "Serbia: Europe's largest proctracted refugee situation". OSCE. 2008.

- ↑ S. Cross, S. Kentera, R. Vukadinovic, R. Nation (7 May 2013). Shaping South East Europe's Security Community for the Twenty-First Century: Trust, Partnership, Integration. Springer. p. 169. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Croatia: European Court of Human Rights to consider important case for refugee returns" (Press release). Amnesty International. 2005-09-14. Archived from the original on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ↑ "Amnesty International | Working to Protect Human Rights". Thereport.amnesty.org. 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- ↑ "Croatia - Amnesty International Report 2008". amnesty.org. Amnesty International. 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ Negativna presuda evropskog suda u slučaju Kristine Blečić iz Zadra Archived 17 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - croatia_t5_iccpr_1510_2006" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-11-17.

- ↑ "ECSR decision in case no 52/2008" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-11-17.

- ↑ "Croatia report". 25 February 2015. Retrieved 2016-01-16.

- ↑ "Croatia 2016/2017report". Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ↑ "PROMENE UDELA STANOVNIŠTVA HRVATSKE I SRPSKE NACIONALNE PRIPADNOSTI U REPUBLICI HRVATSKOJ PO GRADOVIMA I OPŠTINAMA NA OSNOVU REZULTATA POPISA IZ 1991. I 2001. GODINE" (PDF) (in Serbian). 2008. Retrieved 2013-07-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Karoly Kocsis, Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi: Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin, Simon Publications LLC, 2001, p. 171

- ↑ Stanovništvo po narodnosti po popisu od 15. marta 1948. godine, Beograd 1954., p. 3 (in Serbian)

- ↑ Popis stanovništva 1953. godine, p. 35 (in Serbian)

- ↑ Population, households and dwellings census in 1961, National structure of population in FNR Yugoslavia, data on localities and ocmmunes, Vol. III, p. 12 (in Serbian)

- ↑ http://www.dzs.hr/Hrv/censuses/census2011/results/htm/H01_01_04/h01_01_04_RH.html

- ↑ "Serbian Orthodox Church History - St Michael Serbian Orthodox Church". Stmichael-soc.org. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- 1 2 3 4 Miller 1998, p. 13

- 1 2 "Pravoslavci iz Hrvatske više se ne izjašnjavaju kao Srbi!".

- ↑ "Europska povelja o regionalnim ili manjinskim jezicima" (in Croatian). Ministry of Justice (Croatia). 2011-04-12. Retrieved 2012-02-08.

- 1 2 B92 (3 April 2015). "UN calls on Croatia to ensure use of Serbian Cyrillic". Retrieved 2015-04-11.

- ↑ Tanjug (3 April 2015). "Serbia welcomes UN stance on use of Cyrillic in Croatia". Retrieved 2015-04-11.

- ↑ "Population according to native language.".

- ↑ "Pravo pripadnika nacionalnih manjina u Republici Hrvatskoj na zastupljenost u Hrvatskom saboru". Zakon o izborima zastupnika u Hrvatski sabor (in Croatian). Croatian Parliament. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

- 1 2 http://www.novosti.rs/vesti/naslovna/drustvo/aktuelno.290.html:436817-Izbeglice-iz-Hrvatske-Bez-prava-a-Evropljani. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ http://www.politika.rs/rubrike/Drustvo/Srbija-zemlja-sa-najvecim-brojem-izbeglica-u-Evropi.lt.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Episkop Lukijan Musicki". Eparhija-gornjokarlovacka.hr. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- ↑ Archived 15 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Krka časopis br. 6". Eparhija-dalmatinska.hr. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- ↑ History of family Preradović from Gornja Krajina (Grubišno Polje etc) and their relation to the Russian branch (general Nikolay Depreradovich etc), may be seen in the book published in Zagreb, Croatia in 1903, Znameniti Srbi XIX veka, year 2, 2, editor Andra Gavrilović, Zagreb 1903, p. 13. Also, book published in Belgrade in 1888, Milan Đ. Milićević, Pomenik znamenitih ljudi u srpskog naroda novijeg doba, p. 572. For the list of Preradovićs (Serbs) murderd in Jasenovac concentration camp of Independent State of Croatia (NDH) during World War II, including Preradovićs from Grubišno Polje, where father of Petar Preradović was born see (official in Croatia) Jasenovac Memorial site list of victims, where one could see a few Jovan Preradović, as was the name of Petar Preradović's father (http://www.jusp-jasenovac.hr Spomen Područje Jasenovac), or names of 100 Preradovićs on the list of victims on the list of victims of Jasenovac Research Institute, New York City, (https://cp13.heritagewebdesign.com/~lituchy/victim_search.php?field=&searchtype=contains)

- ↑ "Josip Runjanin". Moljac.hr. Retrieved 2012-11-17.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0784884/

- ↑ http://www.arhiva.glas-javnosti.rs/arhiva/2005/04/29/srpski/K05042801.shtml Prota Sava Nakićenović, O hercegnovskim Vojnovićima, Dubrovnik 1910, http://www.srpsko-nasledje.co.rs/sr-c/1998/02/article-13.html Dragomir Acović, Heraldika i Srbi, Beograd 2008, p. 335, http://www.rastko.org.yu/rastko-ukr/istorija/2003-ns/dmartinovic.pdf, http://www.scindeks-clanci.nb.rs/data/pdf/0350-0861/2005/0350-08610553121C.pdf

- ↑ "Peja Stojakovic Biography". JockBio. 1977-06-09. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- ↑ "de beste bron van informatie over jasnasekaric". jasnasekaric.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- ↑ "Biography of His Holiness Patriarch Pavle". Serbianorthodoxchurch.com. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- ↑ "Svetozar Pribicevic (Yugoslavian politician) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- ↑ "Josif Rajacic". Ohiou.edu. 2004-10-25. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

Sources

- Books

- Artuković, Mato (2001). Srbi u Hrvatskoj: Khuenovo doba. (in Croatian)

- Begović, Nikola (1887). Život i običaji Srba-Graničara. Tiskarski zavod "Narodnih novinah". (

Public domain) (in Serbian)

Public domain) (in Serbian) - Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (2006). The Balkans: A Post-Communist History. The Lord Byron Foundation for Balkan Studies. ISBN 9780415229623.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Ćorović, Vladimir (2001) [1997]. Istorija srpskog naroda (Internet ed.). Belgrade: Ars Libri. (in Serbo-Croatian)

- Dakina, Gojo Riste (1994). Genocide Over the Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia: Be Catholic Or Die. Institute of Contemporary History.

- Đurić, Veljko Đ. (1991). Prekrštavanje Srba u Nezavisnoj Državi Hrvatskoj: prilozi za istoriju verskog genocida. Alfa.

- Gavrilović, Slavko (1994). Srbi u Habsburškoj monarhiji: 1792-1849. Matica srpska. (in Serbian)

- Grujić, Radoslav M. (1912). "Најстарија српска насеља по северној Хрватској (до 1597. год)". Гласник Српског географског друштва. 1 (2).

- Ilić, Jovan (1995). "The Serbs in the Former SR of Croatia". The Serbian Questions in The Balkans.

- Ivić, Aleksa (1909). Seoba Srba u Hrvatsku i Slavoniju. (

Public domain) (in Serbian)

Public domain) (in Serbian) - Jačov, Marko (1984). Венеција и Срби у Далмацији у XVIII веку. Просвета.

- Korb, Alexander (2010). "A Multipronged Attack: Ustaša Persecution of Serbs, Jews, and Roma in Wartime Croatia". Eradicating Differences: The Treatment of Minorities in Nazi-Dominated Europe. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 145–163.

- Krestić, Vasilije; Milosavljević, Margot (1997). History of the Serbs in Croatia and Slavonia 1848-1914. Beogradski izdavačko-grafički zavod.

- Leutloff-Grandits, Carolin (2006). Claiming Ownership in Postwar Croatia: The Dynamics of Property Relations and Ethnic Conflict in the Knin Region. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-8258-8049-1.

- Milaš, Nikodim (1901). Pravoslavna Dalmacija : istorijski pregled. Novi Sad: A. Pajevića. (

Public domain) (in Serbian)

Public domain) (in Serbian) - Mileusnić, Slobodan (1997). Spiritual Genocide: A survey of destroyed, damaged and desecrated churches, monasteries and other church buildings during the war 1991-1995 (1997). Belgrade: Museum of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

- Miller, Nicholas J. (1998). Between Nation and State: Serbian Politics in Croatia Before the First World War. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-7722-3.

- Novak, Viktor (2011). Magnum Crimen: Half a Century of Clericalism in Croatia. 1. Jagodina: Gambit.

- Novak, Viktor (2011). Magnum Crimen: Half a Century of Clericalism in Croatia. 2. Jagodina: Gambit.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2008). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Rivelli, Marco Aurelio (1998). Le génocide occulté: État Indépendant de Croatie 1941–1945 [Hidden Genocide: The Independent State of Croatia 1941–1945] (in French). Lausanne: L'age d'Homme.

- Rivelli, Marco Aurelio (1999). L'arcivescovo del genocidio: Monsignor Stepinac, il Vaticano e la dittatura ustascia in Croazia, 1941-1945 [The Archbishop of Genocide: Monsignor Stepinac, the Vatican and the Ustaše dictatorship in Croatia, 1941-1945] (in Italian). Milano: Kaos.

- Rivelli, Marco Aurelio (2002). "Dio è con noi!": La Chiesa di Pio XII complice del nazifascismo ["God is with us!": The Church of Pius XII accomplice to Nazi Fascism] (in Italian). Milano: Kaos.

- Štrbac, Savo (2015). Gone with the Storm: A Chronicle of Ethnic Cleansing of Serbs from Croatia. Knin-Banja Luka-Beograd: Grafid, DIC Veritas.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). The Chetniks. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.

- Journals

- Berber, M.; Grbić, B.; Pavkov, S. (2008). "Changes in the share of ethnic Croats and Serbs in Croatia by town and municipality based on the results of censuses from 1991 and 2001" (PDF). Stanovništvo. 46 (2): 23–62.

- Božić, Sofija (2010). "Serbs in Croatia (1918-1929): Between the myth of “Greater-Serbian Hegemony” and social reality". Balcanica. 41: 185–208.

- Đurđev, Branislav S.; Livada, Svetozar; Arsenović, Daniela (2014). "The disappearance of Serbs in Croatia". Zbornik Matice srpske za drustvene nauke. 148: 583–591.

- Gavrilović, Slavko (1989). "Srbi u Hrvatskoj i Slavoniji u narodnom pokretu 1848-1849". Zbornik o Srbima u Hrvatskoj. Beograd: SANU. 1: 9–32. (in Serbian)

- Gavrilović, Slavko (1991). "Migracije iz Gornje krajine u Slavoniju i Srem od početka XVIII. do sredine XIX. veka". Zbornik o Srbima u Hrvatskoj. Beograd. 2.

- Grujić, Radoslav M. (1912). "Najstarija srpska naselja po severnoj Hrvatskoj". Glasnik srpskog geografskog društva.

- Ilić, J. (2006). "The Serbs in Croatia before and after the break-up of Yugoslavia" (PDF). Zbornik Matice srpske za društvene nauke. Matica srpska. 120: 253–270.

- Ivanović-Barišić, M. M. (2004). "Serbs in Croatia: Ethnological reflections" (PDF). Teme. 28 (2): 779–788.

- Lajić, I.; Bara, M. (2010). "Effects of the war in Croatia 1991-1995 on changes in the share of ethnic Serbs in the ethnic composition of Slavonia" (PDF). Stanovništvo. 48: 49–73.

- Ljušić, Radoš (2012). "The Dalmatian Serbs: One nation and two religions: The examples of Marko Murat and Nikodim Milaš". Anali Pravnog fakulteta u Beogradu. 60 (2): 26–55.

- Roksandić, Drago (1984). "O Srbima u hrvatskim zemljama u Mrkaljevo doba". Književnost. 4–5: 520–534.

- Škiljan, Filip (2009). "Znameniti Srbi u Hrvatskoj" (PDF). Zagreb.

- Škiljan, Filip (2014). "Identitet Srba u Hrvatskoj". Croatian Political Science Review. Zagreb. 51 (2).

- Stojanović, M. (2004). "Serbs in Eastern Croatia" (PDF). Glasnik Etnografskog muzeja u Beogradu. 67-68: 387–390.

- Stokes, Gale (2005). "From nation to minority: Serbs in Croatia and Bosnia at the outbreak of the Yugoslav wars". Problems of Post-Communism. 52 (6): 3–20.

- Trifkovic, Srdjan (2010). "The Krajina Chronicle: A History of Serbs in Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia". Lord Byron Foundation for Balkan Studies.

- Documents

- "OSCE Report on Croatian treatment of Serbs" (PDF). OSCE. 2004.

- "The Status of the Croatian Serb Population in Bosnia and Herzegovina" (PDF). UNHCR.

- Davidov, Dinko, ed. (1992). "War damage sustained by orthodox churches in Serbian areas of Croatia in 1991". Belgrade: Ministry of Information.

- Cleanup

- Karl Freiherr von Czoernig: "Ethnographie der österreichischen Monarchie", Vol. II, III, Wien, 1857

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- John V.A. Fine. (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (2006), When Ethnicity did not matter in the Balkans. A study of Identity in pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-11414-X

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Serbs of Croatia. |

- "Prosvjeta". SKD “Prosvjeta”.

- D. Roksandić, Srbi u Hrvatskoj — od 15. stoljeća do današnjih dana, Vjesnik, Zagreb 1991.

- Tradition chest adornment worn in Kninska Krajina

- Croatian census 2001 (see "Censuses" at Crostat Database)

.jpg)

.jpg)