Dakota Jackson

| Dakota Jackson | |

|---|---|

| Born |

August 24, 1949 Queens, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Designer |

| Website |

www |

Dakota Jackson, (born August 24, 1949) is an American furniture designer known for his eponymous furniture brand, Dakota Jackson, Inc.,[1] his early avant-garde works involving moving parts or hidden compartments,[2][3] and his collaborations with the Steinway & Sons piano company.[1]

Jackson helped establish the art furniture movement in 1970s SoHo,[4][5] later becoming a celebrity designer in the 1980s.[6][7][8] His background in the world of stage magic helped him get his first commissions and is often cited as the source of his point-of-view.[6][9]

Early life

Dakota Jackson (David Malon) was born on August 24, 1949, and grew up in the Rego Park neighborhood of Queens, New York.

Stage Magic

Jackson’s father, Jack Malon, was a professional magician.[10] Mr. Malon learned the trade from his own father, who studied stage magic in early 20th century Poland.[1]

Jackson began studying magic at a young age and sometimes performed with his father.[11] Jackson’s name, in fact, grew out of a road trip to Fargo, North Dakota.[11]

Throughout his adolescence and into his early 20s, Jackson immersed himself in the world of magic.[2] In 1963, Jackson began to perform in talent shows at his junior high school, William Cowper JHS 73 (which is known today as The Frank Sansivieri Intermediate School),[12] and at children’s birthday parties.[13] Jackson also began to build his own props, including large boxes for sawing a woman in half and small boxes from which doves would emerge in full flight.[11] Jackson acknowledges the importance of these early experiences with magic to his later career as a furniture designer: “The demands of performance taught me how to discipline myself to achieve aesthetic ends.”[1][2][14]

After Jackson graduated from Forest Hills High School in 1967, he continued performing as a magician, working in art galleries, night clubs, touring in the Catskills, and giving private performances at society events.[2][13][15] When he was 17, Jackson had studied with magician Jack London to learn the dangerous bullet catch trick.[16]

“What appealed to me was the notion of doing things that appeared miraculous” Jackson once recalled.[6] "I was interested in spiritualism. I was interested in things like bullet catching, things that really challenged individual sensibilities, that were frightening, on the edge."[2]

He didn’t find the opportunity to perform the trick publicly until a decade later at Jackson’s final professional performance as a magician.[1] It was documented in Andy Warhol’s Interview (magazine), in a story titled “Dakota Jackson bites the bullet.”[1][16]

Jackson admits that he sometimes tires of references to his magician background, although he acknowledges it as an important part of his history.[2]

The Downtown Arts Scene

In the late 1960s, Jackson moved into a loft on 28th Street in Chelsea.[1][17] Jackson became part of the Downtown scene, a community of “artists, dancers, performers, and musicians” who moved to the neighborhood for the cheap rent and social life.[1][8][17][18]

In October 1970, Jackson performed with the Japanese group Tokyo Kid Brothers at New York’s La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club (also known as Café La MaMa) in a rock musical production called “Coney Island Play” (“Konī airando purē).[19] The show explored themes of cross-cultural communication and understanding[19] and was a follow up to the group’s debut performance of “The Golden Bat” at La MaMa earlier that summer.[20][21][22] Jackson played the part of a “clever conjurer.”[19]

Over the next few years, Jackson became interested in minimalist dance and performed in the dance companies of Laura Dean and Trisha Brown.[2][15][23]

Jackson credits his exposure to minimalism and minimalist dance in particular as having had a strong influence on his approach to design; in 1989, Jackson told the LA Times:

“For me the essential fineness of a design is in the idea, not the object itself. . . . In minimalism, the object is pared down to its basic meaning by stripping away all the excrescence. . . —those elements that do not contribute to the pure idea.”[24]

Design career

In the early 1970s, as he experimented with performance and dance, Jackson began branching out as a special effects consultant to other magicians, film producers, and musicians[2][23] such as Donna Summer.[6][9]

The loft also gave Jackson an opportunity to apply his creativity and building skills: “These were times when lofts were not . . . luxury condominiums. These were tough, tough raw spaces . . . and we artists, bohemians, creative people, we created our environment. So I had to build”.[17][25]

Recognizing his skills as a builder, Jackson decided to shift away from performance and become a full-time maker.[1][15][17] He began making a variety of objects, including furnishings for other artists and magic boxes with hidden compartments for art collectors and galleries.[17][24] Jackson’s social connections helped spread word about his work[15] and this led to his first commissions.[1]

Early Commissions

In 1974, Jackson’s career as a designer began when Yoko Ono asked him to build a desk with hidden compartments for husband John Lennon.[26] “She wanted to make a piece of furniture that would be a mystical object; that would be like a Chinese puzzle,” Jackson recalled in a 1986 interview published in the Chicago Tribune.[6] The result was a small cubed-shaped writing table with rounded corners reminiscent of Art Deco era style.[15] Touching secret pressure points opened the desk’s compartments.[23] This commission helped build Jackson’s reputation and allowed him to merge his experience as a magician and performer with his developing interest in furniture.[27]

In 1978, a bed designed for fashion designer Diane von Furstenberg garnered Jackson even more notoriety.[8][10][28]

[29] Called “The Eclipse”, the bed was described in The New Yorker as “large, astounding, sumptuous, with sunbursts of cherry wood and quilted ivory satin at head and foot.”[10] A lighting system positioned behind the headboard switched on automatically at sunset and spread out rays of light “like an aurora borealis,”[2][17] which grew brighter and brighter until turning off at 2 am.[23][30]

Commissions like these continued to come in[8] and Jackson soon became known as a designer to the rich and famous.[30] Some of his other clients from this period included songwriter Peter Allen, Saturday Night Live creator and producer Lorne Michaels, Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner, and soap opera actress Christine Jones.[8]

The American Art Furniture Movement and the Industrial Style

In the late 1970s, Jackson was among a small group of artists and artisans producing and exhibiting hand-made furniture in New York.[5][31] Jackson and his peers were part of the “American Art Furniture Movement,” a group sometimes called the “Art et Industrie Movement,”[32] named after the leading art furniture gallery of the era,[32] Art et Industrie, founded by Rick Kaufmann in 1976.[33]

In a 1984 Town & Country article titled “Art You Can Sit On,” Kaufmann said he created the gallery to “serve as a locus to the public for artists and designers creating new decorative arts.”[31] The works on display were “radical objects” that drew from a number of fine art traditions, including “Pop, Surrealism, Pointillism and Dada [which were] “thrown together with the severe lines of the Bauhaus and the Russian avant-garde, mixed with Mondrian’s color and filtered through a video sensibility—all to create a new statement.”[31] The article described Jackson as a “ten-year veteran of the genre” and pointed to the “clean forms and quiet colors” of his furniture.[4]

Jackson showed a variety of industrial-looking lacquer, metal, and glass works at Art et Industrie, including his Standing Bar (also known as the Modern Bar),[33] a lacquered cabinet that Jackson designed in 1978 for his wife (then-girlfriend) RoseLee Goldberg.[13]

Other works from this period include the T-Bird Desk, Self-Winding Cocktail Table, and the Saturn Stool, which became one of Jackson’s most recognizable works[23] after being included in exhibitions at The Whitney, the International Design Center, and the American Craft Museum (now known as the Museum of Arts and Design), and in advertisements for Diane von Fürstenberg and Calvin Klein.[34]

The Sun-Sentinel described the Saturn Stool as “a pink planet seat surrounded by a pale green ring on an aluminum hydraulic lift. . . .”[35] The anodized aluminum and lacquered wood stool[36] became synonymous with Jackson’s work[37] and, a decade later, it was used in an ad for Absolut Vodka titled “Absolut Jackson”.[38]

Jackson called this body of work the Deadly Weapons series.[10][23][39] In concept and style, these works straddled the worlds of art and design[40][41] and drew inspiration from the cutting-edge technology of the day, such as the Rockwell B-1 Lancer, or B1 Bomber as it was commonly known.[39] In 1984, the New York Times described the connection between the fighter jet and another of Jackson’s Deadly Weapons designs, the B1 Desk: “Like the airplane, whose wings shift in flight, the desk has parts that slide open and unfold, including a secret compartment.”[42]

Jackson’s work during this period became associated with the industrial style for home furnishings,[43] a new design trend that was documented in Joan Kron’s and Suzanne Slesin’s 1978 book “High-Tech: The Industrial Style and Source Book for the Home.”[44] In the catalog for The Whitney exhibition “High Styles: Twentieth-Century American Design,” curator Lisa Phillips pointed to Jackson’s Saturn Stool as an example of contemporary products with a “high-tech hardware look.”[43]

Shift to Manufacturing

Curator, poet, and art critic John Perreault included the Saturn Stool in the exhibition “Explorations II: The New Furniture” at the American Craft Museum in 1991. In the exhibition catalog, Perreault linked Jackson’s approach to design with those used in various avant-garde art practices but he also noted Jackson’s reluctance to be labeled as an artist.[40] “In the best of Jackson’s work,” Perreault wrote, "industrial design, craft, and sculpture merge, providing a controversial template for future possibilities.”[45] In a review of the exhibition, New York Times art critic Roberta Smith observed that Jackson’s stool was one of the few objects in the exhibition that seemed ready for mass production.[41]

“I have always wanted to be associated with the craft world, but craft has always been confined to what the hand can do,” Jackson told the Chicago Tribune in an interview about the exhibition.[46] “One-of-a-kind design has a limited appeal to a limited group of collectors,” he continued; “the day of the patron-client relationship is behind us.”[46]

Jackson has often stated that he was inspired by industrialists like Andrew Carnegie[47] to increase production output and create designs that could be manufactured in multiple.[5][48] When he started building in the early 1970s, Jackson was able to complete six pieces a year with the help of a single assistant.[11] In 1976, he relocated from his Chelsea loft and workshop to a larger studio in Lower Manhattan, hiring five assistants.[49] After sales grew to over 100 pieces a year in 1978, Jackson moved again, this time to a 12,500 square foot factory in Long Island City with a staff of 15.[11]

The move to Long Island City allowed Jackson to set up a design studio that was part atelier and part factory.[26] Although he was still making one-of-a-kind commissions,[8] Jackson also designed with production in mind, simplifying forms and eliminating moving parts and hidden compartments.[11] This allowed him to start making lower priced furniture in small production runs.[23]

New Classics Collection

The first collection based on this assembly line[50] approach was the New Classics,[8] which Jackson introduced for the residential furniture market in 1983.[51] “I’ve extracted the signature elements from my work and am moving into a more affordable price range,” Jackson told USA Today.[26] Known for “art-world” priced custom furniture, Jackson likened this reach into a new market to the introduction of a “ready to wear” collection by a “haute couture” designer in the fashion world.[51]

New Classics took aesthetic cues from the Post-modern architecture Movement, which was a reaction to the sparseness of modern architecture and design.[52] Jackson—along with architects Robert Venturi and Michael Graves—helped to define the new style[8] with works that referenced traditional architectural features such as classical proportions, columns, and arches.[52] The collection included a dining table, buffet, armoire, coffee table, and desk, each in a post and lintel design that was easier to reproduce than Jackson’s other more sculptural works.[51]

To help market New Classics to architects and designers serving the residential market, Jackson opened a showroom in Manhattan at the Interior Design Building in 1984.[26][53][54]

Ke-zu Collection

In 1989, Jackson entered the mass-produced contract furniture market[24] with the Ke-zu seating collection, which started with an “angular”[55] chaise longue and grew to include a range of leather-covered arm chairs, side chairs, club chairs, ottomans, and sofas.[24] Like the Saturn Stool, the Ke-zu Chaise came to define Jackson,[56] earning a place in the permanent collection of the Brooklyn Museum and in fashion advertisements of the day.

Vik-ter Chair

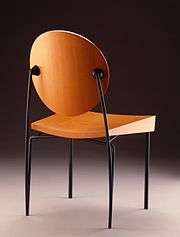

In 1991, Jackson introduced the “biomorphic” Vik-ter Stacking Chair[57] (commonly known as the Vik-ter Chair) at the third annual International Contemporary Furniture Fair at the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in Manhattan.[58] The chair’s “highly production oriented” design included a curving welded-steel frame and a tapered laminated cherry plywood seat that could be produced in seven minutes.[59]

The Vik-ter Chair was Jackson’s first design that could be mass-produced and priced competitively.[60] It received a silver award for environmental design in the 1992 Industrial Design Excellence Awards,[61] awards from I.D., Metropolis, and Interior Design magazines,[62][63][64] and was shown in exhibitions at the Weatherspoon Art Gallery, the American Craft Museum (now known as the Museum of Arts and Design), and the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum.[65][66][67] Both the American Craft Museum and the Cooper-Hewitt obtained the Vik-ter Chair for their permanent collections, and the Cooper-Hewitt also owns a collection of models and drawings relating to the chair’s development.[68]

In the catalog for the exhibition at the Weatherspoon Art Gallery, which was titled “The Chair: From Artifact to Object,” curator Trevor Richardson gives context to Jackson’s achievement with the Vik-ter Chair:

“Between the severity of Minimalism on the one hand, and the exuberance of Memphis on the other, there emerged a new breed of designer who chose to work within the constraints of traditional design languages, while seeking new ways to enrich their existing vocabulary. Far from appearing tired and shopworn, this reworking has, in the hands of individuals such as Jonas Bohlin, Dakota Jackson and Bořek Šípek, attained a new level of refinement and sophistication.”[69]

Although the Vik-ter Chair was designed for the contract market, its popularity led Jackson to make it available to the residential market and for sale directly to buyers through the Museum of Modern Art Design Store Catalog.[59][70]

The Library Chair

In 1991, Jackson began work on a chair for use in libraries and other educational institutions.[9][71][72] Inspired by Bank of England-style office chairs, as well as by the plywood seating collections of Charles and Ray Eames,[73] Jackson spent five years[74] developing and testing his design for what became “The Library Chair” and one of his most ubiquitous works.[8][75]

Jackson wanted to engineer a strong, comfortable wooden chair that could be mass-produced cost-effectively.[73] To achieve this, he turned to Computer Numerical Control cutting technology, or CNC as it is more commonly known,[74] and became one of the first independent furniture manufacturers in the US to acquire the equipment.[5][9] Although “deceptively simple-looking,” Jackson’s design for the Library Chair features compound curves, a hidden Tongue and groove joint between seat and back planes that bend in different directions, and arms that are joined to both the back legs and seat back on either side.[9][73] The CNC cutter’s ability to move though complex cutting operations, switching tools as needed, enabled Jackson’s woodworkers to shape the chair’s components efficiently and with precision.[3][9] Doing this work in-house at his factory in Long Island City allowed Jackson to produce the chair at a low unit cost and sell the chair at a competitive price.[76]

After Jackson exhibited the chair at the International Contemporary Furniture Fair (ICFF) in 1993, Metropolitan Home described it as “simplicity itself” and observed that it marked “design’s new austere mood.”[77] Metropolitan Home also recognized the Library Chair with a “Best of Show” award at the furniture fair, and Jackson received the ICFF Editors Award for Best Body of Work.[78]

The Library Chair was first specified for the San Francisco Public Library’s new Main Library location, which was designed by architect James Ingo Freed of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners and the California architecture firm of Simon Martin-Vegue Winkelstein Moris. The new facility opened in 1996 and required more than a thousand chairs overall, including 722 side chairs and 154 arm chairs for main reading rooms, and 165 upholstered armchairs for the Library’s special collections rooms.[73]

Before Jackson’s chair could be accepted, however, it had to undergo testing at the Forest and Natural Resources Product Laboratory at Purdue University to ensure it could withstand institutional use.[72] It was performance tested twice at Purdue before passing the American Library Association’s LTR standard, which certifies a performance that’s equivalent to 10 years of use in a busy library without failure.[72] One of the tests involved a 250-pound weight, which was dropped on the chair 175,000 times in a row.[73] To increase the strength of the chair, Jackson “experimented with different woods and reinforced the frame with dowels, tenons, finger joints and threaded steel inserts.”[73] The precision-carved parts kept joints between arms, legs, and seat tight.[73]

In 1995, the Library Chair received the ICFF Editors Award for Best Craftsmanship and, in 1997, it was included in the Metropolitan Home “Design 100,” a list of the “World’s Best Ideas and Products.”[74] In 1999, the Cooper-Hewitt added the Library Chair to their permanent collection.

In a 2008 interview with the New York Daily News, Jackson described a moment when he visited a library and saw his chair. “I picked it up to examine it and fresh gum stuck to my hand,” Jackson recalled. It was then that he realized his design was “just a chair—a simple, dumb chair,” and that he had created an institutional chair with longevity. “…It'll be here a lot longer than I will,” he said.[1]

Steinway & Sons

Jackson has collaborated with Steinway & Sons to produce several Limited edition pianos. The first project began in 1998 when Steinway asked Jackson to design the Tricentennial Artcase Grand Piano to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the instrument's invention.[79][80]

In 2014, in honor of Steinway’s 160th anniversary, Jackson and Steinway introduced the 160th Anniversary Limited Edition Arabesque Grand Piano at Steinway Hall.[81] The design, with twisting legs that were inspired by the Arabesque (ballet position),[82] became the first Steinway & Sons piano to receive a Red Dot Design Award for Product Design.[83][84]

Notable projects

- 2014, 160th Anniversary Limited Edition Arabesque Piano (Red Dot Design Award)

- 2007, Scatter Chair (first publicly available Dakota Jackson product)

- 2001, DB-1 and DB-2 Tables (exhibited at the Cooper-Hewitt in 2002)

- 2000, Tri-Centennial Piano (first collaboration with Steinway & Sons)

- 2000, Dumb Box, P.A.

- 1999, Boutique showroom for jewelry designer David Yurman on Madison Avenue

- 1999, Kips Bay Show House

- 1998, Collaboration with architect Peter Eisenman on the Dakota Jackson Los Angeles showroom

- 1997, Bombay Sapphire Goblet

- 1996, Golder Chapel, Temple Jeremiah, Winnetka, Illinois (AIA Religious Art & Architecture Design Award)

- 1995, The Library Chair (acquired by the Cooper-Hewitt in 1999)

- 1995, The Coda Chair for Lane Home Furnishings

- 1992, Absolut Jackson ad for Absolut Vodka

- 1991, Vik-ter Chair (acquired by the Cooper-Hewitt in 1991 and the Museum of Arts and Design in 1993)

- 1988, Ke-zu Chaise (acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in 1990)

- 1984, New Classics Desk (acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in 1990)

- 1979, Self-Winding Cocktail Table

- 1976, Saturn Stool (exhibited at The Whitney in 1985 and acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in 1990)

- 1974, Desk for Yoko Ono and John Lennon (first major commission)

Permanent collections

Museums

- Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago Athenaeum Museum of Architecture and Design, Chicago, IL

- Colorado Ski Museum, Vail, CO

- Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, NY

- Design Museum, London, England

- German Architecture Museum, Frankfurt, Germany

- Museum of Arts and Design, New York, NY

- Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

- Spiritmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden

- Wolfsonian-FIU, Miami Beach, FL

Corporate collections

- Nike, Inc., Beaverton, OR

- Bloomingdale's, New York, NY

- Revlon, New York, NY

- The Gap, Inc., San Francisco, CA

- Columbia Pictures, Culver City, CA

- Oprah Winfrey Network, Chicago, IL

- The Walt Disney Studios, Burbank, CA

- Arista Records, Inc., New York, NY

- Bad Boy Records, New York, NY

- EMI Music, London, England

- Four Seasons Hotel, New York, NY

- Harvard Law School, Cambridge, MA

Public institutions

- San Francisco Public Library, San Francisco, CA

- Santa Monica Public Library

- West Hollywood Public Library

Exhibitions

- 2006, “Take a Seat”, Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase, NY

- 2002, “Skin,” curated by Ellen Lupton, Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, New York, NY

- 1992, “The Cooper-Hewitt Collections: A Design Resource: Designs for Seating”, Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, New York, NY

- 1992, “Initial Concepts: Dakota Jackson”, Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, New York, NY

- 1991, “Explorations II: The New Furniture,” curated by John Perreault, American Craft Museum, New York, NY

- 1991, “The Chair: From Artifact to Object”, Weatherspoon Art Gallery, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, NC

- 1990, “Mondo Materialis,” curated by Jeffrey Osborne and George Beylerian, Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, New York, NY

- 1987, “The Chair Fair,” organized by Architectural League of New York, International Design Center, New York, NY

- 1985, “High Styles: Twentieth-Century American Design,” curated by Lisa Phillips, et al., The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

- 1980, “Further Furniture,” curated by Nicholas Calas, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, NY

Awards and honors

- 2014, Red Dot Design Award, Design Zentrum Nordrhein Westfalen

- 2012, Design Icon Award, Academy of Art University, San Francisco, CA

- 2010, AD 20/21 Lifetime Achievement Award, Boston Architectural College, Boston, MA

- 2006, SCAD Style Étoile Award, Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, GA

- 1997, Design 100 Hall of Fame, Metropolitan Home, New York, NY

- 1997, Good Design Award, The Chicago Athenaeum: Museum of Architecture and Design, Chicago, IL

- 1995, AIA Religious Art & Architecture Design Award, American Institute of Architects, Washington, D.C.

- 1995, ICFF Editors Award: Craftsmanship, International Contemporary Furniture Fair, New York, NY

- 1994, Design 100 Hall of Fame, Metropolitan Home, New York, NY

- 1993, ICFF Editors Award: Body of Work, International Contemporary Furniture Fair, New York, NY

- 1992, Annual Design Review Award, I.D., The International Design Magazine, New York, NY

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Sheftell, Jason (March 6, 2008). "Third-generation magician’s factory makes wonders before your eyes". New York Daily News. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Sherrod, Pamela (May 15, 1994). "The State of Dakota". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 "Furniture designer seems to have magic touch". Standard-Speaker. March 24, 1998. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 Wohlfert-Wihlborg, Lee (September 1984). "Art You Can Sit On". Town & Country: 274.

- 1 2 3 4 Szenasy, Susan (April 2008). "ICFF: 20 Years and Counting". Metropolis. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Daniels, Mary (October 19, 1986). "Keeping The Magic In Furniture Design". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Anderton, Frances (May 14, 1998). "Design Notebook; The Twain Not Only Meet, They Collaborate". New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Jay, Hilary (February 2008). "Performance Artist". Art & Antiques: 96.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nobel, Philip (June 1998). "Decoding Dakota". Metropolis: 78.

- 1 2 3 4 Fraser, Kennedy (June 13, 1983). "The Talk of the Town: Magic". The New Yorker. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Greer, Kimberly (February 24, 1985). "Furniture Designer’s Pieces Spring from Love of Magic". The Victoria Advocate. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "Talent Galore". Long Island Star Journal. 1963.

- 1 2 3 Cheakalos, Christina (March 26, 2001). "Conjurer". People. 55 (12): 127. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "Steinway & Sons Reveals Limited Edition Dakota Jackson ‘Arabesque’ Piano". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jay, Hilary (February 2008). "Performance Artist". Art & Antiques: 95.

- 1 2 "Dakota Jackson bites the bullet". Interview. August 1976.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cheakalos, Christina (March 26, 2001). "Conjurer". People. 55 (12): 125. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Dessen, Michael (2003). Decolonizing Art Music: Scenes from the Late Twentieth-Century United States. U of California, San Diego.

- 1 2 3 Barnes, Clive (October 31, 1970). "The Tokyo Kid Brothers Again—‘Cony Island Play’ also includes Americans". New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "Goings On About Town: Golden Bat". The New Yorker: 3–4. August 22, 1970. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "Tokyo Kid Brothers". The New Yorker: 34–36. September 12, 1970. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Thornbury, Barbara (2013). America’s Japan and Japan’s performing arts: cultural mobility and exchange in New York, 1952–2011. U of Michigan. p. 111.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Van de Water, Ava (March 30, 1987). "Jackson designs ‘furniture to experience’". Indiana Gazette.

- 1 2 3 4 Whiteson, Leon (March 29, 1989). "Design: Dakota Jackson: Much Magic in His Furniture". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Columbia, David Patrick; Hirsch, Jeffrey. "Dakota Jackson". New York Social Diary. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Sporkin, Elizabeth (April 12, 1983). "Designer conjures up magical furniture". USA Today.

- ↑ Jay, Hilary (February 2008). "Performance Artist". Art & Antiques: 95–96.

- ↑ Lane, Jane (August 29, 1978). "Diane Von Furstenberg: ‘I Have a Man’s Life’". Women’s Wear Daily.

- ↑ Duka, John (October 2, 1978). "Dressing a Room: How are fashion designers’ rooms like their clothes?". New York Magazine: 71.

- 1 2 Varkonyi, Charlyne (October 8, 1993). "Dakota Jackson: Stars’ Designer Going Retail". Sun Sentinel. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 Wohlfert-Wihlborg, Lee (September 1984). "Art You Can Sit On". Town & Country: 272.

- 1 2 Johnson, Ken (November 11, 2005). "A Show Where Art, Design and Collectibles Blur". New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 Kimmerle, Constance, ed. (2014). Paul Evans: Crossing Boundaries and Crafting Modernism. Doylestown: Michener Museum. p. 69.

- ↑ "Silk. Shine. Glamour. Legwork by Diane Von Furstenberg". New York Times Magazine: 51. March 16, 1980.

- ↑ Winship, Frederick (September 29, 1985). "20th Century Style Exhibit Shows Ugly Sides of Design". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "Collections: Decorative Arts: Saturn Stool". brooklynmuseum.org. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Carber, Kristine (October 2009). "Furniture with Flair". Spaces: 34. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Savage, Todd (November 3, 1996). "Bottles-up Creativity". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 Beach, Susan (March 2, 1986). "Dakota Jackson’s Designs Contain a Bit of Magic". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 Perreault, John (1991). Explorations II: The New Furniture. American Craft Museum. p. 25.

- 1 2 Smith, Roberta (July 19, 1991). "Art in Review: 'Explorations II: The New Furniture'". New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Giovannini, Joseph (May 31, 1984). "The Enduring Fascination of Secret Places". New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 Phillips, Lisa (1985). High Styles: Twentieth-Century American Design. Summit Books. p. 206.

- ↑ Shapiro, Harriet (April 2, 1979). "Ready for High-Tech?". People. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Perreault, John (1991). Explorations II: The New Furniture. American Craft Museum. p. 8.

- 1 2 Alai, Susan (June 2, 1991). "Barcaloungers Beware! The Form Of This Furniture Makes You Sit Up And Take Notice". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Robinson, Gaile (May 21, 1994). "Dakota Jackson’s Rhythms". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Large, Elizabeth (May 3, 1994). "From one-of-a-kind furniture to mass market, Dakota Jackson has a flamboyant way with design". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "Celebrity Clients Appreciate Furniture Designer’s Style". Toledo Blade. Newsday. May 18, 1984. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Bethany, Marilyn (August 28, 1983). "Home Design; Interior Trends 1984". New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Market: Dakota Jackson Furniture Program". Interior Design: 216. December 1983.

- 1 2 Giovannini, Joseph (August 18, 1983). "Furniture for the Post-Modern Interior". New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Harden, Tracey (June 9, 1983). "Storage: now you see it; now you don’t". New York Daily News. p. 50.

- ↑ "Furniture made with art in mind". News Journal. June 21, 1984.

- ↑ Giovannini, Joseph (June 30, 1988). "Currents: To Recline, With a Sense of Humor". New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Baker, Fiona; Baker, Keith (2000). C 20th Furniture. Carlton Books. p. 235.

- ↑ Hales, Linda (June 16, 1991). "Furniture Takes a Provocative Turn". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Dullea, Georgia (May 23, 1991). "It’s New. It’s Now. Can You Sit in it?". New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 Garet, Barbara (July 1, 1993). "Furniture takes a wacky turn on its way to the fair". Wood & Wood Products. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Garet, Barbara (October 1, 1991). "Impresario of Design". Wood & Wood Products. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "The 1992 IDEA Winners". Businessweek. June 7, 1992. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "38th Annual Design Review". I.D.: The International Design Magazine. August 1992.

- ↑ "Design Explorations 2001". Metropolis. October 1991.

- ↑ "Roscoe Awards, Outstanding Achievement in Product Design". Interior Design. 1992.

- ↑ Richardson, Trevor (1991). Du Pont presents The Chair: from Artifact to Object. Greensboro: Weatherspoon Art Gallery. pp. 30, 36, 54.

- ↑ Perreault, John (1991). Explorations II: The New Furniture. American Craft Museum. p. 60.

- ↑ Louie, Elaine (May 28, 1992). "Currents: Chairs on the Wall". New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Smithsonian Year 1992 Supplement. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. 1992. p. 168.

- ↑ Richardson, Trevor (1991). Du Pont presents The Chair: from Artifact to Object. Greensboro: Weatherspoon Art Gallery. p. 30.

- ↑ Overton, Sharon (October 10, 1993). "Growing strong: Plywood makes a comeback". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Brierly, Susan (September 2010). "Celebrating Simplicity". Park Place Magazine. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 Brown, Carol (2002). Interior Design for Libraries: Drawing on Function and Appeal. American Library Association. p. 74.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Carlson, Julie (April 17, 1996). "A chair for all the pages". SFGate. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 Hirst, Arlene (April 1997). "The New Classics: Collectibles for the Future". Metropolitan Home: 79.

- ↑ Volner, Ian (January 4, 2012). "Designer Dakota Jackson wins Award from Academy of Art University". Interior Design. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Cox, Linda (Winter 1997). Designed in New York: Made in New York. The Municipal Art Society of New York. p. 18.

- ↑ "Hot Properties: At NYC's International Contemporary Furniture Fair, necessity became the mother of style". Metropolitan Home: 16. October 1993.

- ↑ Hales, Linda (May 27, 1993). "Waking Up to Fine Lines of Design: America's Contemporary Furniture Makers Get Serious-But Not Too Serious". The Washington Post. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "Playing On Piano's Artful Potential". August 3, 2000. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Jay, Hilary (February 2008). "Performance Artist". Art & Antiques: 98.

- ↑ Gilroy, Anthony. "Steinway & Sons Unveils Dakota Jackson’s 'Arabesque' Piano". www.steinway.com. Steinway & Sons. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "Steinway's Arabesque". Gramophone: 11. December 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Gilroy, Anthony. "Anniversary 'Arabesque' Wins Prestigious Red Dot for Product Design". www.steinway.com. Steinway & Sons. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ Höpermann, Sabine. "Red Dot Award Ceremony". eu.steinway.com. Steinway & Sons. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

Further reading

- Interview, “Dakota Jackson bites the bullet”; August, 1976

- The New Yorker, “The Talk of the Town: Magic”; June 13, 1983

- New York Times, “Design Notebook; The Twain Not Only Meet, They Collaborate”; May 14, 1998

- Metropolis, “Decoding Dakota”; June, 1998

- People, Conjurer. P March 26, 2001

- Art & Antiques, “Performance Artist”; February 2008

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dakota Jackson. |

- Dakota Jackson Website

- Jackson's Modern Bar

- Interview regarding changes in the high-end furniture industry caused by the Great Recession

- Profile of Jackson as Honorary Chair of Furniture Design at SCAD