Dacian warfare

The history of Dacian warfare spans from c. 10th century BC up to the 2nd century AD in the region defined by Ancient Greek and Latin historians as Dacia. It concerns the armed conflicts of the Dacian tribes and their kingdoms in the Balkans. Apart from conflicts between Dacians and neighboring nations and tribes, numerous wars were recorded among Dacians too.

Mythological

Tribal wars

The Dacians fought amongst each other but were later united first under Burebista and later under Decebalus. Despite this after the death of Burebista[1] at 44 BC they had been split by a civil war.

Domitian's Dacian War

The two punitive expeditions mounted as a border defense against raids of Moesia from Dacia in 86-87 AD ordered by the Emperor Titus Flavius Domitianus (Domitian) in 87 AD, and 88 AD. The first expedition was an unmitigated disaster, and the second achieved a peace, seen as unfavorable and shameful by many in Rome.

Trajan's Dacian Wars

Trajan's Dacian Wars. The two campaigns of conquest ordered or led by the Emperor Trajan in 101-102 AD, and 105-106 AD from Moesia across the Danube north into Dacia. Trajan's forces were successful in both cases, reducing Dacia to client state status in the first, and taking the territory over in the second. These wars involved no less than 13 legions.[2]

Dacian troop types and organization

Infantry and cavalry

The Dacian tribes were part of the greater Thracian family of peoples. They established a highly militarized society and, during the periods when the tribes were united under one king (82 -44 BC, 86-106 AD), posed a major threat to the Roman provinces of Lower Danube. Dacia was conquered (except for the Free Dacians) and transformed into a Roman province in 106 after a long, hard war.

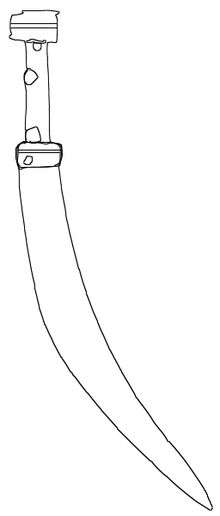

The most important weapon of the Dacian arsenal was the falx. This dreaded weapon, similar to a large sickle, came in two variants: a shorter, one-handed falx called a sica,[3] and a longer two-handed version. The shorter falx was called sica (sickle) in the Dacian language. The two-handed falx was a polearm. It consisted of a three-feet long wooden shaft with a long curved iron blade of nearly-equal length attached to the end. The blade was sharpened only on the inside, and was reputed to be devastatingly effective. However, it left its user vulnerable because, using a two-handed weapon, the warrior could not also make use of a shield. Alternatively, it might be used as a hook, pulling away shields and cutting at vulnerable limbs.

Using the falx, the Dacian warriors were able to counter the power of the compact, massed Roman formations. During the time of the Roman conquest of Dacia (101 - 102, 105 - 106), legionaries had reinforcing iron straps applied to their helmets. The Romans also introduced the use of leg and arm protectors (greaves and manica) as further protection against the falxes.

The Dacians were adept of surprise attacks and skilful, tactical withdrawals using the fortification system. During the wars with the Romans, fought by their last king Decebalus (87-106), the Dacians almost crushed the Roman garrisons south of the Danube in a surprise attack launched over the frozen river ( winter of 101-102 ). Only the intervention of Emperor Trajan with the main army saved the Romans from a major defeat. But, by 106, the Dacians were surrounded in their capital Sarmizegetusa. The city was taken after the Romans discovered and destroyed the capital's water supply line.

Dacians decorated their bodies with tattoos like the Illyrians[4] and the Thracians.[5] The Pannonians north of the Drava had accepted Roman rule out of fear of the Dacians.[6]

Dacia remained a Roman province until 271.

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus[7] 39 - 65 wrote of Dacian hordes;

Have poured her captains, and the troops who guard the northern frontier from the Dacian hordes

Dacians that could afford armor wore customised Phrygian type helmets with solid crests (intricately decorated), domed helmets and Sarmatian helmets.[8] They fought with spears, javelins, falxes, one-sided battle axes and used "Draco" Carnyxes as standards. Most used only shields as a form of defense. Cavalry would be armed with a spear, a long La Tène sword and an oval shield.

Most of the infantry would wield a falx and perhaps a sica and would wear no armor at all even shunning shields.

Mercenaries

Dacian mercenaries were uncommon in contrast to the Thracians and the Illyrians but they could be found in the service of the Greek Diadochi[9] and of the Romans.[10]

Nobility

A 2nd century chieftain would wear a bronze Phrygian type helmet,a corselet of iron scale armor, an oval wooden shield with motifs and wield a sword.[11]

Navy

There was no Dacian navy except perhaps boats to cross the Danube.

Fortifications

Dacians had built fortresses all around Dacia with most of them being on the Danube.[12] A scene from Trajan's column shows Romans attacking a Dacian fortification using the "testudo".[13]

The Dacians constructed stone strongholds, davas, in the Carpathian Mountains in order to protect their capital Sarmizegetusa. The fortifications were built on a system of circular belts. This allowed the defenders, after a stronghold was lost, to retreat to the next one using hidden escape gates.

External influences

Scythian and Sarmatian

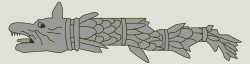

The Dacian Draco was the standard of the ancient Dacian military. It served as a standard for the Dacians of the La Tène period and its origin must clearly be sought in the art of Asia Minor sometime during the second millennium BC.[14]

Sarmatians were part[15] of the Dacian army as allies.The Roxolani became part of the Dacians while the Iazyges fought against them trying to claim their own land.[16]

Celtic and Germanic

Celtic iron spearheads and swords from La Tène.[17] Many types of Hallstatt culture and Celtic swords.[18] Wooden shields, sax knives. The Germanic Bastarnae[19] and Germans[15] were an important part of the Dacian army.Celtic weapons were used like long swords and round shields.[20] The Celts played a very active role in Dacia.[21] The Scordisci were among the allies used by the Dacians.[22]

Greek and Hellenistic

Cothelas had become a vassal to ancient Macedon.Some Kings of the Getae had been Hellenized[23]

Roman

.svg.png)

.jpg)

Part of Dacia became a Roman province at 106 AD, and Dacians were eventually Romanized. After their defeat from the Roman a coin called Dacicus[24] was minted by Domitian.

Barbarians

Dacians were shown by Trajan as dignified[25] and heroic but still dangerous and unable to stand against the might of Rome. 1st century BC poet Horace writes of them in one of his works and mentions them along with the Scythians[26] as tyrants and fierce barbarians. Later historian Tacitus writes that they are a people that can never be trusted[27]

The Ancient Greeks[28] expressed admiration and respect for Burebista.

List of Dacian battles

This is a list of battles or conflicts that Dacians had a leading or crucial role in, rarely as mercenaries. They were involved in massive battles against Roman legions.

- Unknown date. Celtic Boii in Bohemia against Dacian tribes from the lower Danube,[29] Dacian victory

- 1st century BC Dacians against Scordisci,Dacian victory

- 86

- 87, First Battle of Tapae,Dacian victory

- 88

- 101, Second Battle of Tapae,Indecisive Roman victory

- 102, Battle of Adamclisi,Roman victory

- 103, Battle of Gatae,Roman victory

- 105

- 106, Battle of Sarmisegetusa,Roman victory

See also

- List of ancient cities in Thrace and Dacia

- List of ancient tribes in Thrace and Dacia

- List of rulers of Thrace and Dacia

- Thracian warfare

- Illyrian warfare

- Celtic warfare

- Falx

- Sica

References

- ↑ The Legionary by Peter Connolly, 1998, page 14: "... dynamic king Burebista, a century and a half earlier, the Dacians had become the most powerful nation in central Europe, but since his death the country had been split by civil war."

- ↑ A Companion to the Roman Army (Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World) by Paul Erdkamp, 2007, page 218

- ↑ Rome's Enemies (1): Germanics and Dacians (Men at Arms Series, 129) by Peter Wilcox and Gerry Embleton, 1982, page 35

- ↑ The Illyrians by John Wilkes, 1996, page 198: "...their armor is Celtic but they are tattooed like the rest of the Illyrians and Thracians..."

- ↑ The World of Tattoo: An Illustrated History by Maarten Hesselt van Dinter, 2007, page 25: "... in ancient times. The Danube area Dacians, Thracians and Illyrians all decorated themselves with status-enhancing tattoos, ..."

- ↑ The Oxford Classical Dictionary by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, 2003, page 1106, "Pannonia north of the Drava appears to have accepted Roman rule without a struggle probably owing to fear of the Dacians to the east.

- ↑ Luc. 8.331

- ↑ Rome's enemies: Germanics and Dacians by Peter Wilcox, Gerry Embleton, ISBN 0850454735, 1982

- ↑ The Coming of Rome in the Dacian World, ISBN 387940707X, 2000, page 83

- ↑ The Coming of Rome in the Dacian World, ISBN 387940707X, 2000, page 115

- ↑ Rome's Enemies (1): Germanics and Dacians (Men at Arms Series, 129) by Peter Wilcox and Gerry Embleton, 1982

- ↑ Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe by Ion Grumeza, 2009, page 13, "The shores of the Danube were well monitored from the Dacian fortresses Acidava, Buricodava, Dausadava (the shrine of the wolves), Diacum, Drobeta (Turnu Severin), Nentivava (Oltenita), Suvidava (Corabia), Tsirista, Tierna/Dierna (Orsova) and what is today Zimnicea. Downstream were also other fortresses: Axiopolis (Cernadova), Barbosi, Buteridava, Capidava (Topalu), Carsium (Harsova), Durostorum (Silistra), Sacidava/Sagadava (Dunareni) along with still others..."

- ↑ The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare: Volume 2, Rome from the Late Republic to the Late Empire by Philip Sabin, Hans van Wees, and Michael Whitby, 2007, page 149: "... 4.5 Scene from Trajan's column depicting Roman troops attacking a Dacian fortification, using the famous testudo (tortoise) formation to shield themselves from ..."

- ↑ Parvan Vasile (1928) in 'Dacia', Bucuresti, page 125

- 1 2 Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe by Ion Grumeza, 2009, page 170

- ↑ Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe by Ion Grumeza, 2009, page 134

- ↑ Rome's enemies: Germanics and Dacians by Peter Wilcox,Gerry Embleton, ISBN 0850454735, 1982, page 7

- ↑ Rome's enemies: Germanics and Dacians by Peter Wilcox, Gerry Embleton, ISBN 0850454735, 1982, page 9

- ↑ Rome's Enemies: Germanics and Dacians by Peter Wilcox, Gerry Embleton, ISBN 0850454735, 1982, page 35

- ↑ Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe by Ion Grumeza, 2009, page 50

- ↑ Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe by Ion Grumeza, 2009, page 88

- ↑ Strab. 7.5, "...they often used the Scordisci as allies..."

- ↑ The Thracians, 700 BC - AD 46 by Christopher Webber, ISBN 1-84176-329-2, ISBN 978-1-84176-329-3, 2001, page 14, "It shows a Hellenised king of the Getae..."

- ↑ Dacicus, "Dācicus, a gold coin of Domitian, conqueror of the Dacians..."

- ↑ The Barbarians Speak: How the Conquered Peoples Shaped Roman Europe by Peter S. Wells, 2001, page 105, "... so too the Emperor Trajan represented the Dacians as a strong threat to Roman authority on the lower Danube. The barbarian enemies are represented in heroic fashion, as dignified warriors unable ..."

- ↑ Q. Horatius Flaccus (Horace), Odes, John Conington, Ed.Hor. Carm. 1.35, "Thee Dacians fierce, and Scythian hordes, peoples and towns, and Rome, their head, and mothers of barbarian lords, and tyrants in their purple dread,..."

- ↑ Tac. Hist. 3.46, "The Dacians also were in motion, a people which never can be trusted..."

- ↑ Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe by Ion Grumeza, 2009, page 54, "The Greeks were so impressed with his achievements that they named him 'the first and greatest king of the kings of Thracia'...."

- ↑ Celtic Warrior: 300 BC-AD 100 by Stephen Allen and Wayne Reynolds, 2001, Front Matter,"... 60: Celtic Boii in Bohemia defeated by Dacian tribes from the lower Danube. 58-51: Caesar's campaigns in Gaul ..."

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dacia and Dacians. |