Döda fallet

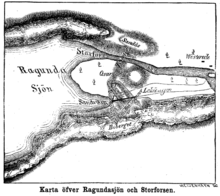

Döda fallet (The dead fall) is a former whitewater rapid in of the river Indalsälven in Ragunda Municipality in the eastern part of the province of Jämtland in Sweden. Glacial debris had blocked the course of the Indalsälven at Döda fallet for thousands of years, creating a reservoir of glacial meltwater 25 km (16 mi) in length known as Lake Ragundasjön.[1] The river water flowed over this dam of debris in a high waterfall known as Gedungsen or Storforsen (The great whitewater rapid).[2] It was one of the most impressive waterfalls in Sweden with a total fall height of about 35 meters (115 feet) and a large water discharge.

The lake and falls were destroyed in 1796 after a flood rerouted the river through a small canal constructed to bypass the falls, emptying the entire lake within hours.[1]

Background

The Indalsälven flows through a valley between mountains in Jämtland province of Sweden. In one place its course before the Ice Age went south of a high rock spur with a round mountain in its end sticking out of the valley's north side. In the Ice Age its course past that spur was filled with glacial and periglacial deposit, and after the ice retreated the river flowed further north, over the neck of the spur, causing Storforsen.

In the late 18th century, logging emerged as a major industry in the heavily forested region of Jämtland. The rivers were used as fast and relatively easy transportation of the timber to the coastal sawmills. The whitewater rapid Storforsen however was a major obstacle as it damaged or destroyed much of the timber, forcing use of land transportation (portaging) past the waterfall. Another issue was that salmon could not swim upstream through Storforsen, and this made the fishing downstream good, but poor upstream.

Because of this, a man named Magnus Huss, also known as Vildhussen (the Wild Huss), was in 1793 appointed to solve the problem by constructing a canal to bypass the waterfall. During 1794 and 1795 preliminary work such as clearing forest was carried out, but work on the canal channel did not begin until 1796, partly due to sabotage by locals who were skeptical or did not want to lose their paid work portaging the timber.

In early 1796 work on the canal started. It was dug through unconsolidated glacial-outwash sand and gravel including an esker, and sand kept running back into the channel, and there was concern about the effect on the fishing, and thus the province's governor ordered a stop to the digging. A new method was tried: a nearby creek was led into a temporary dam-lake, which was released when full, washing much sand away, and this was repeated, steadily further upstream, until it reached Ragundasjön.[3] The spring flood of 1796 was unusually heavy, and lake water started to leak into the canal. The porous ground beneath the canal could not withstand the force of the water, which started to quickly erode deep into the esker. In only four hours in the night of 6/7 June 1796 Ragundasjön drained completely, triggering a 15-metre-high (49 ft) flood wave moving down the river, causing much destruction and establishing the much deepened and scoured-out course of the canal as part of the river's new course, probably thus restoring its old course as before the Ice Age. Although it was one of Sweden's largest environmental disasters, no one is believed to have been killed by the event.[4] The washed-away soil and sediments redeposited at the Indalsälven's delta in the Baltic Sea north of Sundsvall, creating new land which the Sundsvall-Härnösand Airport was later built on. The final judgment on the case (for loss of fishing) came in 1975, 179 years later.

Indalsälven never became navigable. The old lake bed became fertile farmland.

Storforsen, dried, is now called Döda fallet (the Dead Fall). At a rock barrier in the bottom of the former Ragundasjön a new waterfall was formed, Hammarfallet in Hammarstrand, now turned into a hydroelectric power station.[5][6]

Until 1796 varved sediment was accumulating on the bottom of Ragundasjön. That gives geologists an exact date for the last varve there; see Varve for dating by counting varves.

Heritage

Today Döda fallet is a nature reserve and one of the major tourist attractions of the municipality. Every year there is a play commemorating what happened in the spring of 1796. Magnus Huss is remembered by a statue in the small nearby town of Hammarstrand, which was built on the former lake bed of Ragundasjön. Döda fallet is also listed in the Reader's Digest publication Natural Wonders of the World.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. p. 127. ISBN 0-89577-087-3.

- ↑ Baynes, Robert Hall. The Churchman's shilling magazine and family treasury, conducted by R.H. Baynes.

- ↑ http://www.byggbrigaden.se/default.asp?do=visa&id=209 (in Swedish)

- ↑ "En fantastisk historia". Döda fallet. Ragunda municipality. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ↑ http://www.ragunda.se/engelskversion/oururbanareas.4.1493102f93cc527677fff2613.html

- ↑ http://www.ragunda.se/sprak/inenglish/whattodo/deadfalls.4.1493102faeec674fc7fff1083.html

External links

- "Döda fallet". Ragunda turism (in Swedish). Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- About the Ragunda lake-draining event (in Swedish)

- Maps before and after the event

- Google Earth view of Hammarstrand and around

Coordinates: 63°03′14″N 16°31′05″E / 63.054°N 16.518°E