Myxobacteria

| Myxobacteria | |

|---|---|

| |

| Myxococcus xanthus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Proteobacteria |

| Class: | Deltaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Myxococcales |

The myxobacteria ("slime bacteria") are a group of bacteria that predominantly live in the soil and feed on insoluble organic substances. The myxobacteria have very large genomes, relative to other bacteria, e.g. 9–10 million nucleotides except for Anaeromyxobacter[1] and Vulgatibacter. One of the myxobacteria, Minicystis rosea, has the largest bacterial genome with16.04 million nucleotides followed by another myxobacteria Sorangium cellulosum.[2][3] Myxobacteria are included among the delta group of proteobacteria, a large taxon of Gram-negative forms.

Myxobacteria can move by gliding. They typically travel in swarms (also known as wolf packs), containing many cells kept together by intercellular molecular signals. Individuals benefit from aggregation as it allows accumulation of the extracellular enzymes that are used to digest food; this in turn increases feeding efficiency. Myxobacteria produce a number of biomedically and industrially useful chemicals, such as antibiotics, and export those chemicals outside the cell.[4]

Life cycle

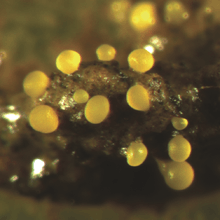

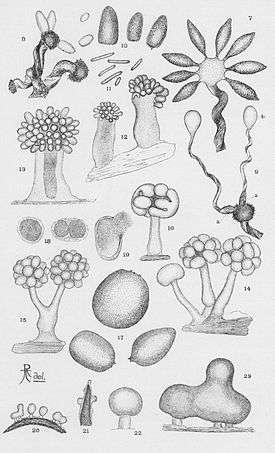

When nutrients are scarce, myxobacterial cells aggregate into fruiting bodies (not to be confused with those in fungi), a process long-thought to be mediated by chemotaxis but now considered to be a function of a form of contact-mediated signaling.[5][6] These fruiting bodies can take different shapes and colors, depending on the species. Within the fruiting bodies, cells begin as rod-shaped vegetative cells, and develop into rounded myxospores with thick cell walls. These myxospores, analogous to spores in other organisms, are more likely to survive until nutrients are more plentiful. The fruiting process is thought to benefit myxobacteria by ensuring that cell growth is resumed with a group (swarm) of myxobacteria, rather than as isolated cells. Similar life cycles have developed among certain amoebae, called cellular slime molds.

At a molecular level, initiation of fruiting body development in Myxococcus xanthus is regulated by Pxr sRNA.[7][8]

Myxobacteria such as Myxococcus xanthus and Stigmatella aurantiaca are used as model organisms for the study of development.

Clinical use

Metabolites secreted by Sorangium cellulosum known as epothilones have been noted to have antineoplastic activity. This has led to the development of analogs which mimic its activity. One such analog, known as Ixabepilone is a U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved chemotherapy agent for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer.[9]

Myxobacteria are also known to produce Gephyronic acid, an inhibitor of eukaryotic protein synthesis and a potential agent for cancer chemotherapy.[10]

References

- ↑ Thomas, Sara H.; Wagner, Ryan D.; Arakaki, Adrian K.; Skolnick, Jeffrey; Kirby, John R.; Shimkets, Lawrence J.; Sanford, Robert A.; Löffler, Frank E. (2008-05-07). "The mosaic genome of Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans strain 2CP-C suggests an aerobic common ancestor to the delta-proteobacteria". PloS One. 3 (5): e2103. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2330069

. PMID 18461135. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002103.

. PMID 18461135. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002103. - ↑ Schneiker S, et al. (2007). "Complete genome sequence of the myxobacterium Sorangium cellulosum". Nature Biotechnology. 25 (11): 1281–1289. PMID 17965706. doi:10.1038/nbt1354.

- ↑ Miriam Land, Loren Hauser, Se-Ran Jun, Intawat Nookaew, Michael R. Leuze, Tae-Hyuk Ahn, Tatiana Karpinets, Ole Lund, Guruprased Kora, Trudy Wassenaar, Suresh Poudel, David W. Ussery (2015). "Insights from 20 years of bacterial genome sequencing". Functional & Integrative Genomics. 15 (2): 141–161. doi:10.1007/s10142-015-0433-4.

- ↑ Reichenbach H (2001). "Myxobacteria, producers of novel bioactive substances". J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 27 (3): 149–56. PMID 11780785. doi:10.1038/sj.jim.7000025.

- ↑ Kiskowski MA, Jiang Y, Alber MS (2004). "Role of streams in myxobacteria aggregate formation". Phys Biol. 1 (3–4): 173–83. PMID 16204837. doi:10.1088/1478-3967/1/3/005.

- ↑ Sozinova O, Jiang Y, Kaiser D, Alber M (2005). "A three-dimensional model of myxobacterial aggregation by contact-mediated interactions". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 102 (32): 11308–12. PMC 1183571

. PMID 16061806. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504259102.

. PMID 16061806. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504259102. - ↑ Yu YT, Yuan X, Velicer GJ (May 2010). "Adaptive evolution of an sRNA that controls Myxococcus development". Science. 328 (5981): 993. PMC 3027070

. PMID 20489016. doi:10.1126/science.1187200. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

. PMID 20489016. doi:10.1126/science.1187200. Retrieved 2010-07-22. - ↑ Fiegna F, Yu YT, Kadam SV, Velicer GJ (May 2006). "Evolution of an obligate social cheater to a superior cooperator". Nature. 441 (7091): 310–4. PMID 16710413. doi:10.1038/nature04677.

- ↑ "FDA Approval for Ixabepilone".

- ↑ SASSE, FLORENZ; STEINMETZ, HEINRICH; HÖFLE, GERHARD; REICHENBACH, HANS (2006-04-19). "Antibiotics from gliding bacteria. No.61. Gephyronic Acid, a Novel Inhibitor of Eukaryotic Protein Synthesis from Archangium gephyra (Myxobacteria). Production, Isolation, Physico-chemical and Biological Properties, and Mechanism of Action.". The Journal of Antibiotics. 48 (1): 21–25. PMID 7868385. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.48.21.

External links

- The Myxobacteria Web Page

- Schwarmentwicklung und Morphogenese bei Myxobakterien on YouTube

- Myxobacteria form Fruiting Bodies on YouTube

- Myxococcus xanthus preying on an E. coli colony on YouTube