Cyclura rileyi

| Cyclura rileyi | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Iguania |

| Family: | Iguanidae |

| Genus: | Cyclura |

| Species: | C. rileyi |

| Binomial name | |

| Cyclura rileyi Stejneger, 1903 | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

Cyclura rileyi, commonly known as the Bahamian rock iguana or the San Salvador rock iguana, is a critically endangered species of lizard native to three island groups in the Bahamas. The species is in decline due to habitat encroachment by human development and predation by feral dogs and cats. There are three subspecies: the Acklins ground iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), the White Cay iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), in addition to the nominotypical subspecies (Cyclura rileyi rileyi ).

Taxonomy and etymology

The San Salvador rock iguana is an endangered species of lizard of the genus Cyclura in the family Iguanidae. First described by Leonhard Stejneger in 1903, it is known commonly in the Bahamas as simply "iguana".[2]

Its generic name Cyclura, is derived from the Greek words cyclos, meaning "circular", and urus meaning "tail", after the thick ringed tail characteristic of all Cyclura iguanas.[3] Its specific name, rileyi, is a Latinized form of the surname of American ornithologist Joseph Harvey Riley,[4] who collected the holotype.[5]

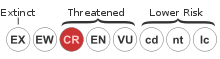

As of 1975 two additional subspecific forms have been identified along with the nominal subspecies: the Acklins ground iguana (C. r. nuchalis) and the White Cay iguana (C. r. cristata).[2] Together they are one of the most threatened species of all the West Indian rock iguanas and are described as critically endangered according to the current IUCN Red List.[1]

Anatomy and morphology

Measuring 300 to 390 mm (12 to 15 in) in snout-to-vent length (SVL) when full grown, the San Salvador rock iguana is a colorful lizard, the coloration varying between subspecies as well as between individual specimens. The lizard's back color can range from red, orange or yellow, to green, brown or grey, usually patterned by darker markings. The very brightest colors (red, orange, blue, or yellow) are normally only displayed by males and are more pronounced when at warmer body temperatures. Immature iguanas lack these bright colors, being either solid brown or grey with faint slightly darker stripes.[1]

This species, like other species of Cyclura, is sexually dimorphic; males are larger than females, and have more prominent dorsal crests as well as larger femoral pores on their thighs, which are used to release pheromones.[6][7]

Distribution

Once inhabiting all the large islands of the Bahamas, today C. rileyi is confined to six populations in small remote cays of three island groups: San Salvador Island, Acklins, and Exuma.[8] A study in 1995 estimated there were between 426 and 639 specimens left in the wild, and that this number has likely been reduced since much of their habitat was destroyed in 1999 by Hurricane Floyd.[9] The three island groups, each harboring its own subspecies, are on separate banks and were not connected during the last glacial period when water levels were 100 m (330 ft) lower than they are at present.[8]

Diet

Like all Cyclura species, the San Salvador rock iguana's diet is primarily herbivorous, 95% of which comes from consuming leaves, flowers and fruits from 7 different plant species such as seaside rock shrub (Rachicallis americana), and erect prickly pear (Opuntia stricta).[8] This diet is very rarely supplemented with insect larvae, crabs, slugs, dead birds and fungi.

Mating

Female San Salvador rock iguanas attain sexual maturity when they reach 20 cm (7.9 in) in length from snout to vent and weigh 300 g (11 oz). Males appear to mature at a slightly larger size, at approximately seven years of age.[8]

Mating occurs in May and June, with clutches of 3-10 eggs usually laid in June or July, in nests excavated in pockets of earth exposed to the sun. Individuals are aggressively territorial from the age of about 3 months.

Conservation

While the island's natives often used iguanas as food and funerary offerings in pre-colonial times, man's largest-scale devastation to these animals was as a result of clear-cutting forests to create plantations as well as the introduction of non-native species.[1] Introduced black rats, raccoons, feral dogs, mongoose, hogs, and cats have taken their toll on the population by direct predation, as have the larvae of a moth (Cactoblastis cactorum), introduced decades ago to the Caribbean, which are rapidly devastating prickly-pear cacti, an important food source for the iguanas.[1] The Guana Cay population has been reduced to less than 24 individual animals.[9]

Other threats by humans include tourists trampling iguanas' nests, iguanas contracting disease from eating human garbage, and illicit smuggling for the pet trade.[1] As development increases on the islands and further isolates populations, these animals will be threatened by lack of gene flow between the cays.[1]

As of August 2007, no legal captive breeding programs exist outside of the Bahamas.[1] The Bahamian government has refused to issue export permits for any rock iguanas.[1] However, Ardastra Gardens in Nassau (New Providence Island, Bahamas) currently holds two juveniles and plans to implement a captive breeding program.[1] A public relations campaign is planned to heighten awareness and appreciation among island residents for this endemic lizard.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Carter, R.L.; Hayes, W.K. (1996). "Cyclura rileyi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 1996: e.T6033A12351578. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- 1 2 Hollingsworth, Bradford D. (2004), "The Evolution of Iguanas: An Overview of Relationships and a Checklist of Species", Iguanas: Biology and Conservation, University of California Press, pp. 38–39, ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1

- ↑ Sanchez, Alejandro (November 26, 2007), Father Sanchez's Web Site of West Indian Natural History Diapsids I: Introduction; Lizards

- ↑ "Riley, Joseph - Biography". Washington Biologists' Field Club; Patuxent Wildlife Research Center.

- ↑ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Cyclura rileyi, p. 222).

- ↑ De Vosjoli, Phillipe; David Blair (1992), The Green Iguana Manual, Escondido, California: Advanced Vivarium Systems, ISBN 1-882770-18-8

- ↑ Martins, Emilia P.; Lacy, Kathryn (2004), "Behavior and Ecology of Rock Iguanas,I: Evidence for an Appeasement Display", Iguanas: Biology and Conservation, University of California Press, pp. 98–108, ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1

- 1 2 3 4 Hayes, William; Carter, Ronald; Cyril, Samuel; Thornton, Benjamin (2004), "Conservation of a Bahamian Rock Iguana, I", Iguanas: Biology and Conservation, University of California Press, pp. 232–243, ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1

- 1 2 Hayes, William K. (2003). "Can San Salvador’s Iguanas and Seabirds Be Saved?". Department of Natural Sciences, Loma Linda University.

Further reading

- Schwartz, Albert; Thomas, Richard (1975). A Check-list of West Indian Amphibians and Reptiles. Carnegie Museum of Natural History Special Publication No. 1. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Carnegie Museum of Natural History. 216 pp. (Cyclura rileyi, p. 114).

- Stejneger, Leonhard (1903). "A New Species of Large Iguana from the Bahama Islands". Proc. Biol. Soc. Washington 16: 129-132. (Cyclura rileyi, new species).

Data related to Cyclura rileyi at Wikispecies

Data related to Cyclura rileyi at Wikispecies

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cyclura rileyi. |