Cuzcatlan

| |

| Capital | Cuzcatlan |

| Official language | Nawat |

| Government | Monarchy tributary Tagatecu (inherited) |

| Establishment Dissolution |

approx.1200 1528 |

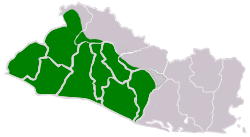

Cuzcatlan was a pre-Columbian Nahuat state of the postclassical period that extended from the Paz river to the Lempa river (covering most of the western and central zones of the present Republic of El Salvador), this was the nation that Spanish chroniclers came to call the Pipils/Cuzcatlecs. No codices or written accounts survive that shed light on this señorío, although Spanish chroniclers such as Domingo Juarros, Palaces, Lozano, and others claim that some codices did exist but have since disappeared. Their language (Nahuat), art and pyramids revealed that they had significant Mayan and Toltec influence. It is believed that the first settlers to arrive came from the Toltec people in central Mexico.

The Nahuat came to be called Pipiles in the historical chronicles, a term that today is usually translated as "childlike" or "young" due to the simplified Nahuat that they spoke, but is more likely at the time to have meant "nobles," comparable to the use of junger in German.

The name "Cuzcatlan" comes from the Nahuatl origin "Kozkatlan" (Cozcatlan Spanish form), which is derived from "Kozkatl", meaning "diamond" or "jewel", and "tlan", meaning "next to" or "in between". Kozkatlan means "The Place of the Diamond Jewels".

Origins

The Nahuat arrived in El Salvador around the year 900 AD. On arrival, they attacked and conquered the native city states by burning towns and establishing their own. Some city states such as Tehuacán allowed them free entrance avoiding destruction and eventually with time they became absorbed into the Cuzcatlan state. Others such as Chalchuapa and Cihuatán became allies with the Nahuat, but also eventually became absorbed. According to legend, the city of Cuzcatlán (the capital city of Cuzcatlan, was founded by the exiled Toltec Ce Acatl Topiltzin, also called Quetzalcoatl, around the year 1054. In the 13th century the Pipil city states were most likely unified, and by 1400, a hereditary monarchy had been established.

Political organization

The Señorío de Cuzcatlán was divided into chieftainships:

- Cuzcatlán

- Izalco

- Apaneca

- Ahuachapán

- Guacotecti

- Ixtepetl

- Apastepeque

- Tehuacán

The chieftainships did not form a unified political system and were at first independent, and were obligated to pay tribute/taxes to the chieftainship of Cuzcatlán. With time, they were all annexed by the chieftainship of Cuzcatlán, today the modern city of Antiguo Cuscatlan a city and municipality that is part of the San Salvador Metropolitan Area (AMSS).

Government

The Señor de Cuzcatlán (lord of Cuzcatlán) was the head of state and had the title of Tagatécu. Below the chief were the Tatoni or princes; below them the state elders and priests who advised the ruling family; then a caste of commoners. Upon the death of a chief, the succession was hereditary starting with the eldest son and so on. In case there were no sons available, the closest male family member was chosen by the counsel of elders and priests.

At the time of the Spanish conquest, Cuzcatlan had developed into a powerful state that maintained a strong standing army. It had successfully resisted Mayan invasions and was the strongest military force in the region.

Tagatécus Or Señores de Cuzcatlán

There were many Tagatécus or Señores of Cuzcatlán; most have been forgotten with time, with the exception of the last four. Historical writings by the Spaniard Domingo Juarros reveal who they were.

- Cuachimicín: Governed before the Spanish conquest, he was overthrown and executed by the priests.

- Tutecotzimit: Successor of the previous one, restored the hereditary system.

- Pilguanzimit

- Tonaltut

Over time, a legend developed that the last king of Cuzcatlan was named Atlacatl, a mistake originating with a misreading of some Spanish accounts. This heroic myth sometimes includes the detail that Atlacatl dealt Alvarado the serious wound in one leg that broke his femur and left it shorter than the other. Historical accounts, however, find no such figure. After the collapse of the Nahuat standing army in the first two battles with Alvarado's forces, Alvarado entered the capital of Cuzcatlan without resistance. Initially the people seemed to accept this conquest, offering gifts and service, but Alvarado soon found that the men were missing and discovered that they had retreated to the mountains. Alvarado then enslaved many of those who remained and returned with his captives to the Mayan region. A second invasion completed the takeover, although the Lenca people in the eastern zone maintained a guerrilla resistance for a further decade. (See Battle of Acajutla).

Military service

Military service was obligatory from about age 15 until they were unable to serve due to age. The soldier's attire consisted of a breastplate, a corselete or vest (made of cotton) and a mashte (species of loin cloth) and each painted their faces and bodies with unique colored abstract shapes and forms. The soldiers were organized in teams or platoons bearing distinctive names, such as:

- The Jaguars

- The Eagles

- The Brave Owls

The soldiers of Cuzcatlan had a variety of weapons, most made of wood and volcanic rock shards. Pedro de Alvarado reported that they also wore thick cotton armor, which were evidently designed to repel the caliber of throwing weapons they themselves had (see list below) as it could not repel Spanish lances. So heavy was this cotton when it became wet, Alvarado reported, that the Nahuat soldiers could not rise from the ground when thrown down. No pictorial depiction of this armor has survived. Some of the documented weapons are described below.

- Tecuz (Lance): there were two types, a long spear that according to the Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado it was 6,30 metres. The second one was a more maneuverable shorter spear.

- Macuáhuit (mallet): made out of strong wood with sharpened obsidian at the end.

- Tahuítul (bow) and Mit (arrows):

- Malacate (disc): Most likely made of sharpened rock and used in the hand-to-hand combat.

Economy

The economy was based on the barter or exchange of agriculture and handcrafted goods such as multicolored textiles.

Cacao was a major export crop that was carefully cultivated in the Izalcos area and traded throughout the isthmus. Its production involved the construction of an elaborate irrigation network, parts of which can still be seen today. cacao served in the region as currency.

Other agricultural products grown by the Pipil were cotton, squash, corn, beans, fruits, balsam, some peppers, and chocolate; but chocolate could only be prepared and served to the ruling class. There was modest mining of gold and silver, although these were not used as currency but as offering to their many gods. Only the priests and the ruling family could use gold and silver as ornaments.

Religion

Through cronistas and archaeology we know that the Señorío de Cuzcatlán was well organized with respect to the priesthood, Gods, rites, etc. One of the peregrination places was the sanctuary to the goddess Nuictlán (constructed by EC Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl) located in the lake of Güija. Human sacrifice was practiced.

Honoring the Creators

The people living in the Señorío of Cuzcatlán attributed cosmic power to the following: Xipe Totec, Quetzalcoatl, Ehécatl, Tláloc, Chacmool, Tonatiuh, Chalchitlicue and others. In addition there were some spirits identified with the Señorío of Cuzcatlán like Itzqueye. Téotl, Quetzalcoatl and Itzqueye were three of the most important to the people's spiritual beliefs.

Fall and end of the Señorío de Cuzcatlán

After the fall of the Aztec Empire under Hernan Cortez, Pedro de Alvarado was sent by Cortez to conquer the native city states further south. After subduing or striking alliances with the Mayan peoples in the highlands, on June 6, 1524, Pedro de Alvarado crossed the Paz river with a few hundred soldiers and thousands of Kaqchikel Mayan allies and subdued the Cacique of Izalco (the first major city state en route to Cuzcatlan). Fierce battles were fought in defense of Izalco in Acaxual (today Acajutla in the Spanish version) and Tacuzcalco. On June 17, de Alvarado arrived in Cuzcatlán. Some of the population acquiesced to his rule; others fled to the mountains.

On the ashes of the once mighty Cuzcatlan in 1525, Pedro de Alvarado's cousin Diego de Alvarado established the Villa De San Salvador. Over the next three years, various attempts by the native Indians to destroy the newly founded town resulted in the decision to move the town a few kilometers south to its present location, to the valley commonly known as "the valley of the hammocks" (due to significant seismic activity) next to the Quezaltepeque (San Salvador) volcano.

Legacy

Archeological sites in El Salvador include Tazumal, which has similarities to Toltec style pyramids. Other sites include San Andres, Cara Sucia, Joya de Ceren and Cihuatan. Otherwise, Cuscatlan is not known for the kind of monumental architecture used by the Classical Maya.

See also

References

Consulted Web Sites

Sites in Spanish:

- Señorío de Cuzcatlán

- Museo arqueológico digital: los pipiles

- Fuerza Armada precolombina de El Salvador

- Historia precolombina de El Salvador

- Museo arqueológico digital: Crónica de Diego García Palacios

- Proyecto Cihuatán

- Asociación Tikal: Investigaciónes en Antiguo Cuscatlán

- Google books: Cronica de Domingo Juarros

- Google books: Manual de Arqueologìa Americana

Coordinates: 13°40′00″N 89°14′00″W / 13.6667°N 89.2333°W