Kuna people

|

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (about 50,000) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Panama, Colombia | |

| Languages | |

| Kuna, Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| traditional Kuna religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Chibchan-speaking people, Miskito |

The Kuna, following orthographic reform in 2010 also known as Guna, and historically as Cuna, are an indigenous people of Panama and Colombia. The Congreso General de la Nación Gunadule since 2010 promotes the spelling Guna. In the Kuna language, they call themselves Dule or Tule, meaning "people", and the name of the language in Kuna is Dulegaya, literally "people-mouth".[2]

Location

The Kuna live in three politically autonomous comarcas or reservations in Panama, and in a few small villages in Colombia. There are also communities of Kuna people in Panama City, Colón, and other cities. The most Kunas live on small islands off the coast of the comarca of Kuna Yala known as the San Blas Islands. The other two Kuna comarcas in Panama are Kuna de Madugandí and Kuna de Wargandí. They are Kuna speaking people who once occupied the central region of what is now Panama and the neighboring San Blas Islands and still survive in marginal areas.

Political and social organization

In Kuna Yala, each community has its own political organization, led by a saila (pronounced "sigh-lah"). The saila is traditionally both the political and spiritual leader of the community; he memorizes songs which relate the sacred history of the people, and in turn transmits them to the people. Decisions are made in meetings held in the Onmaked Nega, or Ibeorgun Nega (Congress House or Casa de Congreso), a structure which likewise serves both political and spiritual purposes. It is in the Onmaked Nega that the saila sings the history, legends and laws of the Kuna, as well as administering the day-to-day political and social affairs. The saila is usually accompanied by one or more voceros who function as interpreters and counselors for the saila. Because the songs and oral history of the Kuna are in a higher linguistic register with specialized vocabulary, the saila's recitation will frequently be followed by an explanation and interpretation from one of the voceros in everyday Kuna language.

Traditionally, Kuna families are matrilinear, with the groom moving to become part of the bride's family. The groom takes the last name of the bride as well.

Today there are 49 communities in Kuna Yala. The region as a whole is governed by the Kuna General Congress, which is led by three Saila Dummagan ("Great Sailas").[3]

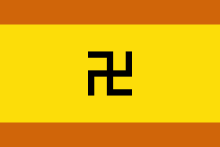

Flag

The Guna Swastika flag was adopted after 1925 rebellion against Panamanian suppression. Horizontal stripes have a proportion of 1:2:1 and the central swastika is an ancestral symbol called Naa Ukuryaa. According to one explanation, it symbolizes the four sides of the world or the origin from which peoples of the world emerged.[4] Also known as the flag of Kuna Yala island today, the flag is used for the province of San Blas and also as Kuna ethnic flag. The central stripe, meaning peace and purity, is white on the official flag of the reservation, officially adopted by Kuna National Congress, while yellow stripe is used on ethnic flag (it was introduced on the flag at about 1940). In 1942 the flag was modified with a red ring encompassing the center of the swastika because of Nazi associations. The addition of a "nose ring" was made "because everyone knows Germans do not wear nose rings." The ring was later abandoned.[5]

Culture

The Kuna are famous for their bright molas, a colorful textile art form made with the techniques of appliqué and reverse appliqué. Mola panels are used to make the blouses of the Kuna women's national dress, which is worn daily by many Kuna women. Mola means "clothing" in the Kuna language. The Kuna word for a mola blouse is Tulemola, (or "dulemola") "Kuna people's clothing."

Economy

The economy of Kuna Yala is based on agriculture, fishing and the manufacture of clothing with a long tradition of international trade. Plantains, coconuts, and fish form the core of the Kuna diet, supplemented with imported foods, a few domestic animals, and wild game. Coconuts, called ogob [IPA: okˑɔβ] in the Kuna language, and lobsters skungit (skuŋkˑit) are the most important export products. Migrant labor and the sale of molas provide other sources of income.

The Kuna have a long deep rooted history of mercantilism and a longstanding tradition of selling goods through family owned venues. Most imported goods originate from Colombian, Mexican or Chinese ships and are sold in small retail stores owned by Kuna people. The Kuna traditionally excise no tax when trading goods and place strong emphasis on economic success. This tradition of trade and self-determination has been credited by many as a chief reason why the Kuna have been able to successfully function independently compared to other indigenous groups.

Kuna communities in Panama City are typically made up of migrant laborers and small business owners, although many Kuna also migrate to Panama City to sell fish and agricultural products produced by their respective communities. The sale of Mola and other forms of Kuna art has become a large part of the Kuna peoples economy in recent years and mola vendors can be found in most cities in Panama where they are marketed to both foreigners and Hispano Panamanians. Tourism is now an important part of the economy in the Carti region, and abandoned goods from the drug trade provide occasional windfalls.

History

The Kunas were living in what is now Northern Colombia and the Darién Province of Panama at the time of the Spanish invasion, and only later began to move westward towards what is now Kuna Yala due to a conflict with the Spanish and other indigenous groups. Centuries before the conquest, the Kunas arrived in South America as part of a Chibchan migration moving east from Central America. At the time of the Spanish invasion, they were living in the region of Uraba and near the borders of what are now Antioquia and Caldas. Alonso de Ojeda and Vasco Núñez de Balboa explored the coast of Colombia in 1500 and 1501. They spent the most time in the Gulf of Urabá, where they made contact with the Kunas.

In far Eastern Kuna Yala, the community of New Caledonia is near the site where Scottish explorers tried, unsuccessfully, to establish a colony in the "New World". The bankruptcy of the expedition has been cited as one of the motivations of the 1707 Acts of Union.

There is a wide consensus regarding the migrations of Kunas from Colombia and the Darien towards what is now Kuna Yala. These migrations were caused partly by wars with the Catio people, but some sources contend that they were mostly due to bad treatment by the Spanish invaders. The Kuna themselves attribute their migration to Kuna Yala to conflicts with the native peoples, and their migration to the islands to the excessive mosquito populations on the mainland.

During the first decades of the twentieth century, the Panamanian government attempted to suppress many of the traditional customs. This was bitterly resisted, culminating in a short-lived yet successful revolt in 1925 known as the Dule Revolution (or people revolution), led by Iguaibilikinya Nele Kantule of Ustupu and supported by American adventurer and part-time diplomat Richard Marsh[6] - and a treaty in which the Panamanians agreed to give the Kuna some degree of cultural autonomy.[6]

The San Blas Islands could be rendered uninhabitable by sea level rise in the late 21st century.[7]

Language

The Kuna language is a Native American language of the Chibchan family spoken by 50,000 to 70,000 people. Dulegaya is the primary language of daily life in the comarcas, and the majority of Kuna children speak the language. Spanish is also widely used, especially in education and written documents. Although it is relatively viable, Kuna is considered an endangered language.

Health

The Kuna have been shown to have a low average blood pressure (BP, 110/70 mm Hg), and, do not experience the age-related increase in blood pressure that is common in Western society (Hollenberg et al. 1997). Death rates from cardiovascular disease and cancer, the #1 and #2 causes of death in the US are low in the Kuna. Between 2000 and 2004, on the mainland of Panama, Bayard et al. (2007) reported that for every 100,000 residents, 119 died from cardiovascular disease (CVD), and 74 died from cancer. In contrast, per 100,000 Kuna, these death rates were 8 for CVD and 4 for cancer.

Albinism

The Kuna have a very high incidence rate of albinism. In Kuna mythology, albinos (or sipus) were given a special place.[8] Albinos in Kuna culture are considered a special race of people, and have the specific duty of defending the Moon against a dragon which tries to eat it on occasion during a lunar eclipse. Only they are allowed to go outside on the night of a lunar eclipse and to use specially made bows and arrows to shoot down the dragon.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kuna. |

- ↑ http://www.panama-mola.com/history-en.htm

- ↑ Erice, Jesus. Diccionario de la Lengua Kuna. Impresora La Nacion (INAC), 1985.

- ↑ Website of Congreso General Kuna

- ↑ http://paseandoteporelperuyelmundo.blogspot.hr/2013_05_05_archive.html

- ↑ http://www.crwflags.com/FOTW/flags/pa-nat.html

- 1 2 James Howe. A PEOPLE WHO WOULD NOT KNEEL: Panama, the United States, and the San Blas Kuna (Smithsonian Series in Ethnographic Inquiry). Smithsonian, 1998. ISBN 978-1-56098-865-6

- ↑ Rising Sea Levels Threaten Tiny Islands Home To Indigenous Panamanians

- ↑ Oculocutaneous albinism: clinical, historical and anthropological aspects PMID 9759297

Further reading

- Alí, Maurizio. 2010: "En estado de sitio: los kuna en Urabá. Vida cotidiana de una comunidad indígena en una zona de conflicto". Universidad de Los Andes, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Departamento de Antropología. Bogotá: Uniandes. ISBN 978-958-695-531-7.

- Bayard V, Chamorro F, Motta J, Hollenberg NK. Does flavanol intake influence mortality from nitric oxide-dependent processes? Ischemic heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, and cancer in Panama. Int J Med Sci. 2007 Jan 27;4(1):53-8.

- Hollenberg NK, Martinez G, McCullough M, et al. Aging, acculturation, salt intake, and hypertension. Hypertension. 1997; 29:171-176.

- James Howe. A people who would not kneel: Panama, the United States, and the San Blas Kuna. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998. ISBN 978-1-56098-890-8.

- James Howe. The Kuna Gathering: Contemporary Village Politics in Panama. Wheatmark (2002). ISBN 978-1-58736-111-1.

- Keeler, Clyde E. Secrets of the Cuna earthmother: a comparative study of ancient religions. Exposition Press, 1960.

- Erland Nordenskiöld et al. An Historical and Ethnological Survey of the Cuna Indians. AMS Press (1979). ISBN 978-0-404-15150-8.

- Mari L. Salvador et al. The Art of Being Kuna: Layers of Meaning Among the Kuna of Panama. University of Washington Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-930741-60-0.

- Joel Sherzer. Kuna Ways of Speaking: An Ethnographic Perspective. Wheatmark, 2001. ISBN 978-1-58736-030-5.

- Joel Sherzer. Verbal Art in San Blas: Kuna Culture Through Its Discourses. University of New Mexico Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-8263-1882-4.

- Joel Sherzer et al. Stories, Myths, Chants, and Songs of the Kuna Indians. University of Texas Press (2003). ISBN 978-0-292-70237-0.

- Karin Elaine Tice. Kuna Crafts, Gender, and the Global Economy. University of Texas Press (1995). ISBN 978-0-292-78137-5.

- Jorge Ventocilla et al. Plants and Animals in the Life of the Kuna. University of Texas Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-292-78726-1.