Cultural area

In anthropology and geography, a cultural region, cultural sphere, cultural area or culture area refers to a geographical area with one relatively homogeneous human activity or complex of activities (culture). These are often associated with an ethnolinguistic group and the territory it inhabits. Specific cultures often do not limit their geographic coverage to the borders of a nation state, or to smaller subdivisions of a state. Cultural "spheres of influence" may also overlap or form concentric structures of macrocultures encompassing smaller local cultures. Different boundaries may also be drawn depending on the particular aspect of interest, such as religion and folklore vs. dress and architecture vs. language.

Cultural areas are not considered equivalent to Kulturkreis (Culture circles).

History of the concept

A culture area is a concept in cultural anthropology, in which a geographic region and time sequence (age area) is characterized by substantially uniform environment and culture.[1] The concept of culture areas was originated by museum curators and ethnologists during the late 1800s as means of arranging exhibits. Clark Wissler and Alfred Kroeber further developed the concept on the premise that they represent long-standing cultural divisions.[2][3][4] The concept is criticized by some, who argue that the basis for classification is arbitrary. But other researchers disagree and the organization of human communities into cultural areas remains a common practice throughout the social sciences.[1] The definition of culture areas is enjoying a resurgence of practical and theoretical interest as social scientists conduct more research on processes of cultural globalization.[5]

Types

A formal culture region is an area inhabited by people who have one or more cultural traits in common, such as language, religion, or system of livelihood. It is an area relatively homogeneous with regard to one or more cultural traits. The geographer who identifies a formal culture region must locate cultural borders. Because cultures overlap and mix, such boundaries are rarely sharp even if only a single cultural trait is mapped so there are cultural border zones rather than lines. The zones broaden with each additional cultural trait that is considered because no two traits have the same spatial distribution. As a result, instead of having clear borders, formal culture regions reveal a center or core where the defining traits are all present. Away from the central core, the characteristics weaken and disappear. Thus, many formal culture regions display a core-periphery.

In contrast to the abstract cultural homogeneity of a formal culture region, a functional culture region may not be culturally homogeneous; instead, it is an area that has been organized to function politically, socially, or economically as one unit: a city, an independent state, a precinct, a church diocese or parish, a trade area or a farm. Functional culture regions have nodes or central points where the functions are coordinated and directed, such as city halls, national capitols, precinct voting places, parish churches, factories, and banks. In this sense, functional regions also possess a core-periphery configuration, in common with formal culture regions. Many functional regions have clearly defined borders that include all land under the jurisdiction of a particular urban government; clearly delineated on a regional map by a line distinguishing between one jurisdiction and another.

Vernacular, popular or perceptual cultural regions are those perceived to exist by their inhabitants, as is evident by the widespread acceptance and use of a distinctive regional name. Some vernacular regions are based on physical environmental features; others find their basis in economic, political or historical characteristics. Vernacular regions, like most culture regions, generally lack sharp borders, and the inhabitants of any given area may claim residence in more than one such region. It grows out of people's sense of belonging and identification with a particular region. An American example is "Dixie". They often lack the organization necessary for functional regions although they may be centered on a single urban node. They frequently do not display the cultural homogeneity that characterizes formal regions.

Allen Noble gave a summary of the concept development of cultural regions using the terms "cultural hearth" (no origin of this term given), "cultural core" by Donald W. Meinig[6] for Mormon culture published in 1970 and "source area" by Fred Kniffen (1965) and later Henry Glassie (1968) for house and barn types. Outside of a core area he quoted Meinigs' use of the terms "domain" (a dominant area) and "sphere" (area influenced but not dominant).[7]

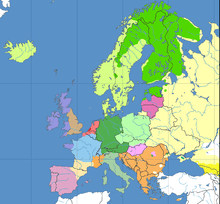

Cultural boundary

A cultural boundary (also cultural border) in ethnology is a geographical boundary between two identifiable ethnic or ethno-linguistic cultures. A language border is necessarily also a cultural border (language being a significant part of a society's culture), but it can also divide sub-groups of the same ethno-linguistic group along more subtle criteria, such as the Brünig-Napf-Reuss line in German-speaking Switzerland, the Weißwurstäquator in Germany or the Grote rivieren boundary between Dutch and Flemish culture.

In the history of Europe, the major cultural boundaries are found

- in Western Europe between Latin Europe, where the legacy of the Roman Empire remained dominant, and Germanic Europe, where it was significantly syncretized with Germanic culture

- in the Balkans, the Jireček Line, dividing the area of dominant Latin (Western Roman Empire) from that of dominant Greek (Eastern Roman Empire) influence.

Macro-cultures on a continental scale are also referred to as "worlds", "spheres" or "civilizations", such as the Muslim world.

In a modern context, a cultural boundary can also be a division between subcultures or classes within a given society, such as blue collar vs. white collar etc.

- See also: Isogloss

Role in conflict

Cultural boundaries sometimes define the difference between friend and foe in political and military conflicts. For example, many religious wars have been fought to forcibly convert people of a different religion, or to put more territory under control of leaders of a particular religion.

Ethnic nationalism and pan-nationalism sometimes seek to unify all native speakers of a particular language - who are conceived of as a coherent ethnic group or nation - into a single nation-state with a unified culture. The association of an ethnolinguistic group with a nation-state may be written into nationality laws and repatriation laws which establish eligibility for citizenship based on ethnicity rather than place of birth.

In other cases, attempts have been made to divide countries based on cultural boundaries, through secession or partition. For example, the Quebec sovereignty movement seeks to separate French-speaking province from English-speaking Canada to preserve its unique language and culture. The Partition of India created separate majority-Hindu and majority-Muslim countries.

Examples

- East–West dichotomy: the notion of a Western civilization contrasting with both the Near East and the Far East

- Language families:

- Individual languages

- Anglosphere

- Francophonie

- Hispanidad

- Lusosphere (Portuguese-speaking countries)

- German language in Europe

- Hindi Belt

- Sinophone

- Geographic

- Religious

Music

A music area is a cultural area defined according to musical activity. It may or may not conflict with the cultural areas assigned to a given region. The world may be divided into three large music areas, each containing a "cultivated" or classical musics "that are obviously its most complex musical forms," with, nearby, folk styles which interact with the cultivated, and, on the perimeter, primitive styles:[9]

- Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa

- based on shared isometric materials, diatonic scales, and polyphony based on parallel thirds, fourths, and fifths.

- would usually use the natural major scale and minor scale, and Dorian, Lydian and Mixolydian modes.

- North Africa, Southwest Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, Indonesia and parts of Southern Europe.

- based on shared small intervals in scales, melodies, and polyphony.

- would usually use the harmonic minor scale and the Phrygian scale.

- American Indian, East Asia, Northern Siberian, and Finno-Ugric music

- based on shared large steps in pentatonic and tetratonic scales.

However, he then adds that "the world-wide development of music must have been a unified process in which all peoples participated" and that one finds similar tunes and traits in puzzlingly isolated or separated locations throughout the world.[9]

See also

- Classification of indigenous peoples of the Americas

- List of music areas in the United States

- Sprachbund

- Julian Steward

- Melville J. Herskovits

- Regionalism (politics)

- Bioregionalism

- Cultural landscape

- Deep map

- Cultural tourism

- Continent

- World language

References

- 1 2 Brown, Nina "Friedrich Ratzel, Clark Wissler, and Carl Sauer: Culture Area Research and Mapping" University of California, Santa Barbara, CA.Brown, Nina "Friedrich Ratzel, Clark Wissler, and Carl Sauer: Culture Area Research and Mapping" University of California, Santa Barbara, CA. Webarchive of http://www.csiss.org/classics/content/15;

- ↑ Wissler, Clark (ed.) (1975) Societies of the Plains Indians AMS Press, New York, ISBN 0-404-11918-2 , Reprint of v. 11 of Anthropological papers of the American Museum of Natural History, published in 13 pts. from 1912 to 1916.

- ↑ Kroeber, Alfred L. (1939) Cultural and Natural Areas of Native North America University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

- ↑ Kroeber, Alfred L. "The Cultural Area and Age Area Concepts of Clark Wissler" In Rice, Stuart A. (ed.) (1931) Methods in Social Science pp. 248-265. University of Chicago Press, Chicago;

- ↑ Gupta, Akhil and James Ferguson (1997). Culture, Power, Place: Explorations in Critical Anthropology. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- ↑ Meinig, D. W., "The Mormon Culture Region: Strategies and Patterns in the Geography of the American West, 1847-1964" Annals of the Association of American Geographers 60 no. 3 1970 428-46.

- ↑ Noble, Allen George, and M. Margaret Geib. Wood, brick, and stone: the North American settlement landscape. Volume 1: Houses, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1984. 7.

- ↑ Marty, Martin (2008). The Christian World: A Global History. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-58836-684-9.

- 1 2 Nettl, Bruno (1956). Music in Primitive Culture, p.142-143. Harvard University Press.

- Zelinsky, Wilbur (1 January 1980). "North America's Vernacular Regions". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 70 (1): 1–16. JSTOR 2562821. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1980.tb01293.x.

Bibliography

- Philip V. Bohlman, Marcello Sorce Keller, and Loris Azzaroni (eds.), Musical Anthropology of the Mediterranean: Interpretation, Performance, Identity, Bologna, Edizioni Clueb – Cooperativa Libraria Universitaria Editrice, 2009.

- Marcello Sorce Keller, “Gebiete, Schichten und Klanglandschaften in den Alpen. Zum Gebrauch einiger historischer Begriffe aus der Musikethnologie”, in T. Nussbaumer (ed.), Volksmusik in den Alpen: Interkulturelle Horizonte und Crossovers, Zalzburg, Verlag Mueller-Speiser, 2006, pp. 9–18

External links

![]() Media related to Cultural regions at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cultural regions at Wikimedia Commons