Culture jamming

Culture jamming (sometimes guerrilla communication)[1][2] is a tactic used by many anti-consumerist social movements[3] to disrupt or subvert media culture and its mainstream cultural institutions, including corporate advertising. It attempts to "expose the methods of domination" of a mass society to foster progressive change.[4]

Culture jamming is a form of subvertising.[5] Many culture jams are intended to expose questionable political assumptions behind commercial culture. Tactics include re-figuring logos, fashion statements, and product images as a means to challenge the idea of "what's cool".[6] Culture jamming often entails using mass media to produce ironic or satirical commentary about itself, commonly using the original medium's communication method.

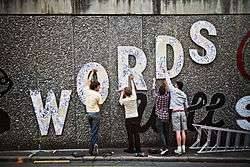

Culture jamming is employed as a reaction against social conformity. Prominent examples of culture jamming include the adulteration of billboard advertising by the Billboard Liberation Front (BLF), and contemporary artists such as Ron English. Culture jamming may involve street parties and protests. While culture jamming usually focuses on subverting or critiquing political and advertising messages, some proponents focus on a more positive (often musically inspired) form which brings together artists, scholars, and activists to create new types of cultural production that transcend—rather than merely criticize—the status quo.[7][8]

Origins of the term, etymology, and history

1984 coinage

The term was coined in 1984 by Don Joyce[9] of the sound collage band Negativland, with the release of their album JamCon '84.[10][11][12] The phrase "culture jamming" comes from the idea of radio jamming:[11] that public frequencies can be pirated and subverted for independent communication, or to disrupt dominant frequencies.[13] In one of the tracks of the album, they stated:[11]

As awareness of how the media environment we occupy affects and directs our inner life grows, some resist. The skillfully reworked billboard... directs the public viewer to a consideration of the original corporate strategy. The studio for the cultural jammer is the world at large.

Origins and preceding influences

According to Vince Carducci, although the term was coined by Negativland, culture jamming can be traced as far back as the 1950s.[14] One particularly influential group that was active in Europe was the Situationist International and was led by Guy Debord. The SI asserted that in the past humans dealt with life and the consumer market directly. They argued that this spontaneous way of life was slowly deteriorating as a direct result of the new "modern" way of life. Situationists saw everything from television to radio as a threat [15] and argued that life in industrialized areas, driven by capitalist forces, had become monotonous, sterile, gloomy, linear, and productivity driven. In particular, the SI argued humans had become passive recipients of the spectacle, a simulated reality that generates the desire to consume, and positions humans as obedient consumerist cogs within the efficient and exploitative productivity loop of capitalism.[8][16] Through playful activity, individuals could create situations, the opposite of spectacles. For the SI, these situations took the form of the dérive, or the active drift of the body through space in ways that broke routine and overcame boundaries, creating situations by exiting habit and entering new interactive possibilities.[8]

The cultural critic Mark Dery traces the origins of culture jamming to medieval carnival, which Mikhail Bakhtin interpreted, in Rabelais and his World, as an officially sanctioned subversion of the social hierarchy. Modern precursors might include: the media-savvy agit-prop of the anti-Nazi photomonteur John Heartfield, the sociopolitical street theater and staged media events of 1960s radicals such as Abbie Hoffman, the German concept of Spaßguerilla, and in the Situationist International (SI) of the 1950s and 1960s. The SI first compared its own activities to radio jamming in 1968, when it proposed the use of guerrilla communication within mass media to sow confusion within the dominant culture. In 1985, the Guerrilla Girls formed to expose discrimination and corruption in the artworld.[17]

Mark Dery's New York Times article on culture jamming, "The Merry Pranksters And the Art of the Hoax"[11] was the first mention, in the mainstream media, of the phenomenon; Dery later expanded on this article in his 1993 Open Magazine pamphlet, Culture Jamming: Hacking, Slashing, and Sniping in the Empire of the Signs,[18] a seminal essay that remains the most exhaustive historical, sociopolitical, and philosophical theorization of culture jamming to date. Adbusters, a Canadian publication espousing an environmentalist critique of consumerism and advertising, began promoting aspects of culture jamming after Dery introduced founder and editor Kalle Lasn to the term through a series of articles he wrote for the magazine. In her critique of consumerism, No Logo, the Canadian cultural commentator and political activist Naomi Klein examines culture jamming in a chapter which focuses on the work of Jorge Rodriguez-Gerada. Through an analysis of the Where the Hell is Matt viral videos, researchers Milstein and Pulos analyze how the power of the culture jam to disrupt the status quo is currently being threatened by increasing commercial incorporation.[8] For example, T-Mobile utilized the Liverpool street underground station to host a flashmob to sell their mobile services.

Tactics

Culture jamming is a form of disruption that plays on the emotions of viewers and bystanders. Jammers want to disrupt the unconscious thought process that takes place when most consumers view a popular advertising and bring about a détournement.[15] Activists that utilize this tactic are counting on their meme to pull on the emotional strings of people and evoke some type of reaction. The reactions that most cultural jammers are hoping to evoke are behavioral change and political action. There are four emotions that activists often want viewers to feel. These emotions – shock, shame, fear, and anger – are believed to be the catalysts for social change.[19]

The basic unit in which a message is transmitted in culture jamming is the meme. Memes are condensed images that stimulate visual, verbal, musical, or behavioral associations that people can easily imitate and transmit to others. The term meme was coined and first popularized by geneticist Richard Dawkins, but later used by cultural critics such as Douglas Rushkoff, who claimed memes were a type of media virus.[20] Memes are seen as genes that can jump from outlet to outlet and replicate themselves or mutate upon transmission just like a virus.[21] Culture jammers will often use common symbols such as the McDonald's golden arches or Nike swoosh to engage people and force them to think about their eating habits or fashion sense.[22] In one example, jammer Jonah Perreti used the Nike symbol to stir debate on sweatshop child labor and consumer freedom. Perreti made public exchanges between himself and Nike over a disagreement. Perreti had requested custom Nikes with the word "sweatshop" placed in the Nike symbol. Nike refused. Once this story was made public over Perreti's website, it spread worldwide and contributed to the already robust conversation[23] and dialogue about Nike's use of sweatshops,[22] which had been ongoing for a decade prior to Perreti's 2001 stunt. Jammers can also organize and participate in mass campaigns. Examples of cultural jamming like Perreti's are more along the lines of tactics that radical consumer social movements would use. These movements push people to question the taken-for-granted assumption that consuming is natural and good and aim to disrupt the naturalization of consumer culture; they also seek to create systems of production and consumption that are more humane and less dominated by global corporate hypercapitalism.[24] Past mass events and ideas have included "Buy Nothing Day", "Digital Detox Week", virtual sit-ins and protests over the Internet, producing ‘subvertisements' and placing them in public spaces, and creating and enacting ‘placejamming' projects where public spaces are reclaimed and nature is re-introduced into urban places.[25]

The most effective form of jamming is to use an already widely recognizable meme to transmit the message. Once viewers are forced to take a second look at the mimicked popular meme they are forced out of their comfort zone. Viewers are presented with another way to view the meme and forced to think about the implications presented by the jammer.[15] More often than not, when this is used as a tactic the jammer is going for shock value. For example, to make consumers aware of the negative body image that big-name fashion brands are frequently accused of causing, a subvertisement of Calvin Klein's 'Obsession' was created and played worldwide. It depicted a young woman with an eating disorder throwing up into a toilet.[26]

Another way that social consumer movements hope to utilize culture jamming effectively is by employing a metameme. A metameme is a two-level message that punctures a specific commercial image, but does so in a way that challenges some larger aspect of the political culture of corporate domination.[22] An example would be the "true cost" campaign set in motion by Adbusters. "True Cost" forced consumers to compare the human labor cost and conditions and environmental drawbacks of products to the sales costs. Another example would be the "Truth" campaigns that frequented television in the past years that exposed the deception tobacco companies used to sell their products.

Following critical scholars like Paulo Freire, Culture jams are also being Integrated into the university classroom "setting in which students and teachers gain the opportunity not only to learn methods of informed public critique, but also to collaboratively use participatory communication techniques to actively create new locations of meaning."[8] For example, students disrupt public space to bring attention to community concerns or utilize subvertisments to engage with media literacy projects.

Examples

- Artivist

- Billboard hacking

- Broadcast signal intrusion

- Flash mob

- Happening

- Practical joke topics

- Steal This Book

- Groups

- Guerrilla Girls

- The Yes Men

- Billboard Liberation Front

- Crimethinc

- Merry Pranksters

- Operation Mindfuck

- Billboard Utilising Graffitists Against Unhealthy Promotions

Criticism

Culture jamming is sometimes confused with artistic appropriation or with acts of vandalism which have destruction or defacement as their primary goal. Although the end result is not always easily distinguishable from these activities, the intent of those participating in culture jamming differs from that of people whose intent is either artistic or merely destructive. The lines are not always clear-cut; some activities, notably street art, will fall into two or even all three categories.

Recently there have been arguments against the validity and effectiveness of culture jamming. Some argue that culture jamming is easily co-opted and commodified by the market, which tends to "defuse" its potential for consumer resistance.[27] Others posit that the culture jamming strategy of rhetorical sabotage, used by Adbusters, is easily incorporated and appropriated by clever advertising agencies, and thus is not a very powerful means of social change.[25] Yet other critics argue that without moving beyond mere critique to offering an alternative economic, social, cultural and/or political vision, jams quickly lose their power and resonance.[7]

See also

- Doppelgänger brand image

- Subvertising

- Banksy

- Critical theory

- The Firesign Theatre

- Minority influence

- Tactical media

Notes

- ↑ Images of the street: planning, identity, and control in public space By Nicholas R. Fyfe, p.274

- ↑ Gavin Grindon Aesthetics and Radical Politics

- ↑ "Investigating the Anti-consumerism Movement in North America: The Case of Adbusters';" Binay, Ayse; (2005); dissertation, University of Texas

- ↑ p.5 Culture Jamming: Ideological Struggle and the Possibilities for Social Change ; 2008; Nomai, Afsheen Joseph; retrieved ???

- ↑ Anthony Joseph Paul Cortese (2008). Provocateur: Images of Women and Minorities in Advertising. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-7425-5539-6. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ↑ Boden, Sharon and Williams, Simon J. (2002) "Consumption and Emotion: The Romantic Ethic Revisited", Sociology 36(3):493–512

- 1 2 LeVine, Mark (2005) Why They Don't Hate Us: Lifting the Veil on the Axis of Evil. Oxford, UK: Oneworld Publications.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Milstein, Tema; Pulos, Alexis (2015-09-01). "Culture Jam Pedagogy and Practice: Relocating Culture by Staying on One's Toes". Communication, Culture & Critique. 8 (3): 395–413. ISSN 1753-9137. doi:10.1111/cccr.12090.

- ↑ "Don Joyce (2/9/44 – 7/22/15)". Negativland.

- ↑ Lloyd, Jan (2003) Culture Jamming: Semiotic Banditry in the Streets, in Cultural Studies Department: University of Canterbury, Christchurc

- 1 2 3 4 Dery, Mark (1990)The Merry Pranksters And the Art of the Hoax, NYtimes article, December 23, 1990.

- ↑ Dery, Mark (2010) New Introduction and revisited edition of Culture Jamming: Hacking, Slashing, and Sniping in the Empire of the Signs, October 8th, 2010

- ↑ Disrupt Dominant Frequencies

- ↑ Carducci, Vince (2006) "Culture Jamming: A Sociological Perspective", Journal of Consumer Culture 6(1): 116–38

- 1 2 3 Lasn, Kalle (1999) Culture Jam: How to Reverse America's Suicidal Consumer Binge – And Why We Must. New York: HarperCollins

- ↑ Debord, Guy (1983). Society of the spectacle. Detroit: Black and Red.

- ↑ Mark Dery."A Brief Introduction to the 2010 Reprint (open source)." Culture Jamming: Hacking, Slashing, and Sniping in the Empire of Signs

- ↑ Dery, Mark (1993) Culture Jamming: Hacking, Slashing, and Sniping in the Empire of the Signs, in Open Magazine Pamphlet Series, 1993

- ↑ Summers-Effler, Erika (2002) "The Micro Potential for Social Change: Emotion, Consciousness, and Social Movement Formation", Sociological Theory 20(1): 41–60

- ↑ Rushkoff, Douglas (1996) Media Virus! New York: Ballantine

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (1989) The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- 1 2 3 Center for Communication and Civic Engagement, Seattle, Washington Retrieved November 20, 2009

- ↑ , Business Insider Retrieved February 9, 2015

- ↑ Princen, Thomas, Maniates, Michael and Conca, Ken (2002) Confronting Consumption. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- 1 2 Harold, Christine (2004) `Pranking Rhetoric: "Culture jamming" as Media Activism', Critical Studies in Media Communication 21(3): 189–211

- ↑ Bordwell, Marilyn (2002) `Jamming Culture: Adbusters' Hip Media Campaign against Consumerism', in Thomas Princen, Michael Maniates and Ken Conca (eds) Confronting Consumption, pp. 237–53. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press

- ↑ Rumbo, Joseph D. (2002) "Consumer Resistance in a World of Advertising Clutter: The Case of Adbusters", Psychology & Marketing 19(2): 127–48.

References

- Dery, Mark (1993). Culture Jamming: Hacking, Slashing, and Sniping in the Empire of Signs. Open Magazine Pamphlet Series: NJ."Shovelware". Markdery.com. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- King, Donovan (2004). University of Calgary. Optative Theatre: A Critical Theory for Challenging Oppression and Spectacle

- Klein, Naomi (2000). No Logo London: Flamingo.

- Kyoto Journal: Culture Jammer's Guide to Enlightenment

- Lasn, Kalle (1999) Culture Jam. New York: Eagle Brook.

- LeVine, Mark (2005) Why They Don't Hate Us: Lifting the Veil on the Axis of Evil. Oxford, UK: Oneworld Publications.

- Perini, Julie (2010). "Art as Intervention: A Guide to Today's Radical Art Practices". In Team Colors Collective. Uses of a Whirlwind: Movement, Movements, and Contemporary Radical Currents in the United States. AK Press. ISBN 9781849350167.

- Tietchen, T. Language out of Language: Excavating the Roots of Culture Jamming and Postmodern Activism from William S. Burroughs' Nova Trilogy Discourse: Berkeley Journal for Theoretical Studies in Media and Culture. 23, Part 3 (2001): 107–130.

- "Culture Jamming". helterskelter.in.

- Milstein, Tema & Pulos, Alexis (2015). Culture Jam Pedagogy and Practice: Relocating Culture by Staying on One's Toes". Communication, Culture & Critique 8 (3): 393-413.