Croatian Littoral

| Croatian Littoral Hrvatsko primorje | |

|---|---|

| Geographic region of Croatiaa | |

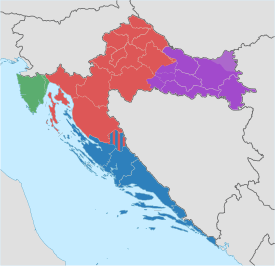

Croatian Littoral on a map of Croatia Croatian Littoral Sometimes considered part of the Croatian Littoral | |

| Country |

|

| Largest city | Rijeka |

| Areab | |

| • Total | 2,830 km2 (1,090 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)b | |

| • Total | 228,725 |

| • Density | 81/km2 (210/sq mi) |

|

a Croatian Littoral is not designated as an official region; it is a geographic region only. b The figure is an approximation based on the territorial span and population of the municipalities bounded by geographic regions of Istria, Mountainous Croatia, and Dalmatia, including the Kvarner Gulf islands. | |

Croatian Littoral (Croatian: Hrvatsko primorje) is a region of Croatia comprising the area between Dalmatia to the south, Mountainous Croatia to the north and east, and Istria and the Kvarner Gulf of the Adriatic Sea to the west. The term "Croatian Littoral" developed relatively recently, since the 18th and 19th centuries, reflecting the complex development of Croatia in historical and geographical terms. The term Croatian Littoral is also applied to entire Adriatic coast of modern Croatia in general terms, which is then divided into the Southern Croatian Littoral comprising Dalmatia, and the Northern Croatian Littoral comprising Istria and Croatian Littoral in the strict meaning of the term. Croatian Littoral covers 2,830 square kilometres (1,090 square miles) and has a population of 228,725. More than half the region's population lives in the city of Rijeka—by far the largest urban centre in the area.

The foothills of mountains that form the northeast boundary of the region, as well as islands in the Kvarner Gulf, are a part of the Dinaric Alps, making karst topography especially prominent in the Croatian Littoral. The Cres – Lošinj and Krk – Rab island chains divide the Kvarner Gulf into four distinct areas—Rijeka Bay, Kvarner (sensu stricto), Kvarnerić, and Vinodol Channel. The Cres – Lošinj group also includes the inhabited islands of Ilovik, Susak, Unije, Vele Srakane, and Male Srakane, as well as a larger number of small uninhabited islands. Zadar Archipelago extends to the southeast of the island group. Water significantly contributed to the geomorphology of the area, especially in the Bay of Bakar, a ria located between Rijeka and Kraljevica. The most significant inland bodies of water in the region are the 17.5-kilometre (10.9-mile) long Rječina River and Lake Vrana on the island of Cres.

The region saw frequent changes to its ruling powers since classical antiquity, including the Roman Empire, the Ostrogoths, the Lombards, the Byzantine Empire, the Frankish Empire, and the Croats, some of whose major historical heritage originates from the area—most notably the Baška tablet. The region and adjacent territories became a point of contention between major European powers, including the Republic of Venice, the Kingdom of Hungary, and the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires, as well as Austria, the First French Empire, the Kingdom of Italy, and Yugoslavia.

Geography

Croatian Littoral is a geographical region of Croatia comprising the area between Dalmatia to the south, Mountainous Croatia to the north and east, and Istria and the Kvarner Gulf of the Adriatic Sea to the west. The region encompasses a large part of Primorje-Gorski Kotar County and the coastal part of Lika-Senj County. The island of Pag is sometimes included in the region, although it is normally considered to be part of Dalmatia.[1] The islands of Cres, Lošinj, Krk, and Rab, as well as further comparatively small nearby islands,[2] are also considered part of the region, contributing to an alternate name for the region—Kvarner Littoral or Kvarner.[3] Various definitions exist as to the extent of "Croatian Littoral" and "Kvarner Littoral" as geographical terms. Specifically, Kvarner Littoral is variously considered to extend east to Senj, or even further east.[4] On the other hand, Kvarner is normally considered to include Istria east of Učka mountain,[5] making Kvarner synonymous with the coastal areas and islands of Primorje-Gorski Kotar County.[6] The term "Croatian Littoral" developed relatively recently, since the 18th and 19th centuries, reflecting the complex development of Croatia in historical and geographical terms. The term is also applied to the entire Adriatic coast of modern Croatia in general terms, which is then divided into the Southern Croatian Littoral comprising Dalmatia, and the Northern Croatian Littoral comprising Istria and Croatian Littoral in the strict meaning of the term.[1]

Croatian Littoral covers 2,830 square kilometres (1,090 square miles), has a population of 228,725, and the region as a whole has a population density of 80.82/km2 (209.3/sq mi). The islands, encompassing 1,120 square kilometres (430 square miles), are home to 39,450 residents.[7][8] More than half the region's population lives in the city of Rijeka—by far the largest urban centre in the area. All other settlements in the region are relatively small, with only four of them exceeding a population of 4,000: Crikvenica, Mali Lošinj (the largest island settlement), Senj, and Kostrena.[9]

| Cities and municipalities of the Croatian Littoral | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| County | City or municipality | Area (km²) | Population |

| Lika-Senj | Karlobag | 287 | 923 |

| Senj | 663 | 7,165 | |

| Primorje-Gorski Kotar | Bakar | 63 | 865 |

| Baška | 101 | 1,668 | |

| Cres | 292 | 2,853 | |

| Čavle | 85 | 7,215 | |

| Dobrinj | 55 | 2,023 | |

| Kastav | 11 | 10,472 | |

| Klana | 94 | 1,978 | |

| Kraljevica | 18 | 4,568 | |

| Krk | 111 | 6,243 | |

| Kostrena | 12 | 4,179 | |

| Lopar | 26 | 1,247 | |

| Mali Lošinj | 223 | 8,070 | |

| Malinska-Dubašnica | 39 | 3,142 | |

| Novi Vinodolski | 262 | 5,131 | |

| Omišalj | 39 | 2,987 | |

| Punat | 82 | 1,953 | |

| Rab | 102 | 7,994 | |

| Rijeka | 44 | 128,735 | |

| Vinodol | 152 | 3,549 | |

| Viškovo | 19 | 14,495 | |

| Vrbnik | 50 | 1,270 | |

| TOTAL: | 2,830 | 228,725 | |

| Sources: Croatian Bureau of Statistics,[9] United Nations Development Programme,[7] Primorje-Gorski Kotar County[8] | |||

| The most populous urban areas in Croatian Littoral | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | City | County | Urban population | Municipal population | ||||||

| 1 | Rijeka | Primorje-Gorski Kotar | 127,498 | 128,735 | ||||||

| 2 | Crikvenica | Primorje-Gorski Kotar | 6,880 | 11,193 | ||||||

| 3 | Mali Lošinj | Primorje-Gorski Kotar | 5,990 | 8,070 | ||||||

| 4 | Senj | Lika-Senj | 4,822 | 7,165 | ||||||

| 5 | Kostrena | Primorje-Gorski Kotar | 4,158 | 4,179 | ||||||

| Sources: Croatian Bureau of Statistics, 2011 Census[9] | ||||||||||

Topography and geology

The foothills of mountains that form the northeast boundary of the region, as well as islands in the Kvarner Gulf, are part of the Dinaric Alps, linked to a fold and thrust belt continuously developing from the Late Jurassic to recent times. The thrust belt is a part of the Alpine orogeny and extends southeast from the southern Alps.[10] Geomorphologically the region was formed as the Adriatic Plate is subducted under structural units comprising the Dinaric Alps. The process formed several seismic faults, with most significant among them being the Ilirska Bistrica – Rijeka – Senj fault, which was the source of several significant earthquakes in past centuries.[11] The Dinaric Alps in Croatia encompass the regions of Gorski Kotar and Lika in the immediate hinterland of the Croatian Littoral, as well as considerable parts of Dalmatia. Their northeastern edge runs from 1,181-metre (3,875 ft) Žumberak to the Banovina region, along the Sava River,[12] and their westernmost landforms are the 1,272-metre (4,173 ft) Ćićarija and the 1,396-metre (4,580 ft) Učka mountains in Istria to the west of the Croatian Littoral region.[13]

Karst topography makes up about half of Croatia and is especially prominent in the Dinaric Alps and the Croatian Littoral.[14] Though most of the soil in the region developed from carbonate rock, flysch is significantly represented on the Kvarner Gulf coast opposite Krk.[15] The karst topography developed from the Adriatic Carbonate Platform, where karstification largely began after the final raising of the Dinarides in the Oligocene and Miocene epochs, when carbonate rock was exposed to atmospheric effects such as rain; this extended to 120 metres (390 ft) below the present sea level, exposed during the Last Glacial Maximum's sea level drop. It is surmised that some karst formations are related to earlier drops of sea level, most notably the Messinian salinity crisis.[16]

Cres – Lošinj and Krk – Rab island chains divide the Kvarner Gulf into four distinct areas: Rijeka Bay, Kvarner (sensu stricto), Kvarnerić, and Vinodol Channel. The Cres – Lošinj group also includes the inhabited islands of Ilovik, Susak, Unije, Vele Srakane, and Male Srakane, as well as a larger number of small, uninhabited islands. Zadar Archipelago extends to the southeast of the island group.[17] The Krk – Rab island group includes only uninhabited islands in addition to Krk and Rab, the largest among them Plavnik, Sveti Grgur, Prvić, and Goli Otok. The Krk – Rab island group is usually thought to represent a single archipelago with the island of Pag (southeast of Rab) and islets surrounding Pag.[18][19]

| Data on the populated islands of Croatian Littoral as of 31 March 2001 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Island | Population[13] | Area[13] | Highest point[13] | Population density |

Coordinates |

| Krk | 17,860 | 405.78 km2 (100,270 acres) | 568 m (1,864 ft) | 44.0/km2 (0.178/acre) | 45°4′N 14°36′E / 45.067°N 14.600°E |

| Rab | 9,480 | 90.84 km2 (22,450 acres) | 410 m (1,350 ft) | 104.4/km2 (0.422/acre) | 44°46′N 14°46′E / 44.767°N 14.767°E |

| Lošinj | 7,771 | 74.68 km2 (18,450 acres) | 589 m (1,932 ft) | 104.1/km2 (0.421/acre) | 44°35′N 14°24′E / 44.583°N 14.400°E |

| Cres | 3,184 | 405.78 km2 (100,270 acres) | 639 m (2,096 ft) | 7.8/km2 (0.032/acre) | 44°57′N 14°24′E / 44.950°N 14.400°E |

| Susak | 188 | 3.8 km2 (940 acres)[20] | 98 m (322 ft)[20] | 49.5/km2 (0.200/acre) | 44°31′N 14°18′E / 44.517°N 14.300°E |

| Ilovik | 104 | 5.2 km2 (1,300 acres)[21] | 92 m (302 ft)[21] | 20.0/km2 (0.081/acre) | 44°28′N 14°33′E / 44.467°N 14.550°E |

| Unije | 90 | 16.92 km2 (4,180 acres) | 132 m (433 ft) | 5.3/km2 (0.021/acre) | 44°38′N 14°15′E / 44.633°N 14.250°E |

| Vele Srakane | 8 | 1.15 km2 (280 acres)[22] | 59 m (194 ft)[22] | 5.3/km2 (0.021/acre) | 44°35′N 14°19′E / 44.583°N 14.317°E |

| Male Srakane | 2 | 0.61 km2 (150 acres)[23] | 40 m (130 ft)[24] | 3.3/km2 (0.013/acre) | 44°34′N 14°20′E / 44.567°N 14.333°E |

| Note: All the islands are located in the Primorje-Gorski Kotar County. | |||||

Hydrology and climate

The availability of water varies significantly throughout the region. The area between Rijeka and Vinodol contains numerous freshwater springs that are largely tapped for water supply systems.[25] Water significantly contributed to the geomorphology of the area, especially in the Bay of Bakar, a ria located between Rijeka and Kraljevica.[26] At the seaward slopes of Velebit, in areas near Senj and Karlobag, surface watercourses are sparse. They form losing streams flowing to the sea, while springs of lower yield dry up during summer.[27] The most significant watercourse in the region is the 17.5-kilometre (10.9-mile) long Rječina River,[28] flowing into the Adriatic Sea in the city of Rijeka.[29] The islands of Cres, Krk, and Lošinj have significant surface water that is used as the primary water supply source on those islands. The most significant among them is Lake Vrana on the island of Cres, containing 220,000,000 cubic metres (7.8×109 cubic feet) of water.[28] The surface of the freshwater lake is at 16 metres (52 feet) above sea level, while its maximum depth is 74 metres (243 feet).[13] The Gulf of Kvarner is an especially significant area for the preservation of biodiversity.[30]

The Kvarner Gulf islands and the immediate mainland coastal areas enjoy a moderately warm and rainy hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Cfa), although the southern part of the Lošinj Island enjoys hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Csa) as defined by the Köppen climate classification. Areas of the Croatian Littoral further away from the coast enjoy a moderately warm and rainy oceanic climate (Cfb), similar to the continental climate of most inland regions of Croatia.[31] The mean monthly temperature varies throughout the region. On the mainland coast it ranges between 5.2 °C (41.4 °F) (in January) and 23 °C (73 °F) (in July). On the Kvarner Gulf islands the mean monthly temperature is somewhat higher; it ranges from 7.3 °C (45.1 °F) (in January) to 23.8 °C (74.8 °F) (in July), while at higher elevations, in the mountains found along the northern and eastern peripheral areas of the region, temperatures range between −1.2 °C (29.8 °F) (in January) and 16.8 °C (62.2 °F) (in July).[32] The lowest air temperature recorded in the region, −16.6 °C (2.1 °F), was measured in Senj, on 10 February 1956.[33] The islands of Lošinj, Cres, Krk, and Rab receive the most sunshine during the year—with 217 clear days per year on average. Seawater temperatures reach up to 26 °C (79 °F) in summer, while dipping to 16 °C (61 °F) in spring and autumn and as low as 10 °C (50 °F) in winter.[32] The predominant winter winds are the bora and sirocco. The bora is significantly conditioned by wind gaps in the Dinaric Alps bringing cold and dry continental air—the point where it reaches its peak speed is at Senj, with gusts of up to 180 kilometres per hour (97 kn; 110 mph). The sirocco brings humid and warm air, often carrying Saharan sand that causes rain dust.[34]

| Climate characteristics in major cities in Croatian Littoral | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Mean temperature (daily high) | Mean total rainfall | ||||||||

| January | July | January | July | |||||||

| °C | °F | °C | °F | mm | in | days | mm | in | days | |

| Rijeka | 8.7 | 47.7 | 27.7 | 81.9 | 134.9 | 5.31 | 11.0 | 82.0 | 3.23 | 9.1 |

| Source:World Meteorological Organization[35] | ||||||||||

History

Middle Ages

In the Early Middle Ages, after the decline of the Roman Empire, the Adriatic coasts of the region were ruled by Ostrogoths, Lombards, and the Byzantine Empire.[36][37] The Carolingian Empire arose in the last part of the period and subsequently the Frankish Kingdom of Italy took control of the Adriatic Sea's western coast extending to the Kvarner Gulf,[38] while Byzantine control of the opposite coast gradually shrunk following the Avar and Croatian invasions starting in the 7th century.[39] The region was gradually incorporated into the medieval Kingdom of Croatia by the 11th century, when the kingdom reached its territorial peak, and the city of Senj became the most important centre of the region. Items of significance to Croatian historical heritage originated from the region in that period. The most notable among them is the Baška tablet, one of the oldest surviving inscriptions in the Croatian language.[40]

The region continued to be contested throughout the High Middle Ages as the Republic of Venice started to expand its influence and territory,[41] gradually pushing back Croatia, which had been in a personal union of Croatia and Hungary since 1102.[42] By 1420, Venice controlled Istria and Dalmatia, as well as all the Kvarner Gulf islands except Krk. The island became a part of the realm in 1481, but Venice never captured the region's mainland, which would have entirely linked Venetian possessions in the eastern Adriatic.[43]

Habsburg era

Ottoman conquests led to the Battle of Krbava field (1493) and the Battle of Mohács (1526), both decisive Ottoman victories, the latter of which caused a succession crisis in the Kingdom of Hungary. In the 1527 election in Cetin, Ferdinand I of Habsburg was chosen as the new ruler of Croatia, under the condition that he provide protection to Croatia against the Ottoman Empire,[44][45] which had extended as far as Lika in the immediate hinterland of the region since 1522.[46] As the region became a point of contention between the Habsburgs, Ottomans, and Venetians, its defense was given high importance in the newly established Croatian Military Frontier, as exemplified by the Uskoks of Senj. After the Ottoman conquest of their original base in Klis, the Uskoks established a new headquarters in Nehaj Fortress as a bulwark against westward expansion by the Ottomans. They also launched raids against Christian communities under Ottoman rule and Venetian commerce and subjects.[47] Increasing conflict between the Uskoks and Venice culminated in 1615 – 1617 Uskok War, which resulted in the resettling of the Uskoks, whose final years in Senj were marked by piracy and looting.[48] Between 1684 and 1689, the Ottomans were forced to retreat from Lika and the entire hinterland of the region.[46]

In 1797 the Republic of Venice was abolished after the French conquest.[49] The Venetian territory was then handed over to the Archduchy of Austria. The territory was returned to France after the Peace of Pressburg in 1805. However, the former Venetian possessions on the eastern Adriatic shore, including the present-day Croatian Littoral, were joined into a set of separate provinces of the French Empire: the Illyrian Provinces,[50] created in 1809 through the Treaty of Schönbrunn.[51] Days before the Battle of Waterloo, the Congress of Vienna awarded the Illyrian Provinces (spanning from the Gulf of Trieste to the Bay of Kotor) to the Austrian Empire.[52]

In 1816 the Kingdom of Illyria—an Austrian crown land—was carved out of the former French possession. The territory originally included Carinthia, Carniola, Gorizia and Gradisca, Trieste, Istria, Rijeka, and Civil Croatia south of the Sava River, corresponding to present-day Croatian Littoral and Mountainous Croatia, except the island of Rab.[53] The island and the rest of the former Illyrian Provinces were made a separate crown land, named Kingdom of Dalmatia, in 1817.[54] Rijeka and Civil Croatia were restored to the Kingdom of Croatia and thus the Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen in 1822,[53] reflecting a series of 18th-century royal letters patent assigning Rijeka to Civil Croatia and the Kingdom of Hungary,[55] giving rise to use of the term "Hungarian Littoral" (Hungarian: Magyar partvidék).[56]

Illyria was abolished in 1849 and the crown lands of Carinthia, Carniola, and Austrian Littoral (German: Österreichisches Küstenland) were established in its place, with the latter including the Krk and Cres – Lošinj island groups.[57] Through the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement of 1868 a corpus separatum was formed containing the city of Rijeka, as a territory directly controlled by Hungary.[58] In 1881, the military frontier, containing the Senj and Velebit foothills, was absorbed by the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia.[59][60]

20th century

Following World War I, the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, and the Treaty of Trianon, Hungary lost its possessions in the region.[61][62] In 1918, a short-lived, unrecognised State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs was formed out of parts of Austria-Hungary, comprising most of the former monarchy's Adriatic coastline and the entire present-day Croatian Littoral. Later that year, the Kingdom of Serbia and the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs formed the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes—subsequently renamed to Yugoslavia. The new union's proponents at the time in the Croatian Parliament saw the move as a defence against Italian expansionism such as via provisions of the 1915 Treaty of London.[63] The treaty was largely disregarded by Britain and France because of conflicting promises made to Serbia and a perceived lack of Italian contribution to the war effort outside Italy itself.[64]

The 1919 Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye did transfer the Austrian Littoral to Italy, but awarded Dalmatia to Yugoslavia.[65] Following the war, a private force of demobilized Italian soldiers seized Rijeka and set up the Italian Regency of Carnaro—seen as a harbinger of Fascism—to force the recognition of Italian claims to the city.[66] After sixteen months of the Regency's existence, the 1920 Treaty of Rapallo redefined the Italian–Yugoslav borders, among other things transferring Zadar and the islands of Cres, Lastovo, and Palagruža to Italy, securing the island of Krk for Yugoslavia, and establishing the Free State of Fiume; this new state was abolished in 1924 by the Treaty of Rome that awarded Rijeka to Italy and Sušak to Yugoslavia.[67]

In April 1941, Yugoslavia was occupied by Nazi Germany and Italy, the latter annexing or occupying the Croatian Littoral, although the armistice between Italy and Allied armed forces of World War II and the 1947 Treaty of Peace with Italy reversed wartime Italian territorial gains, awarding the entire region and adjacent territory to Yugoslavia and the Federal State of Croatia.[68] After the fall of communism, Yugoslavia broke apart as Slovenia and Croatia declared independence in 1991.[69] Although the region suffered an economic decline during the Croatian War of Independence, there was no fighting in the region.[70]

Culture

Since classical antiquity, the area around Kvarner Bay has been characterized as a meeting point of diverse cultures—from Hellenic and Roman cultures, through the Middle Ages and a succession of various rulers, to the present day.[71] This blending is reflected in the folklore of the area, including Zvončari—bell-ringers best known for annual pageant in Kastav, listed on UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[72] Crossbowmen from Rab are a living history company reenacting an arbalest tournament first held in 1364 to commemorate the successful defence of the island using that weapon. A typical decorative motif used in the region is morčić (plural: morčići)—a dark skinned Moor used as a centerpiece on jewelry, usually earrings. Legend has it that the motif is related to a hypothesized battle between Croatian and Ottoman armies on Grobnik north of Rijeka, but it is more likely that it is of Venetian origin, as it is similar to the Venetian moretti motif, used mostly on brooches and pins.[73]

The earliest architectural heritage of the region includes ruins of Roman and Byzantine buildings throughout the area and early medieval Croatian burial grounds in the Vinodol area. There are preserved examples of the Romanesque architecture on the island of Krk, in Vinodol, and in the Kastav area—largely churches, monasteries, and fortifications such as Drivenik Castle. Several preserved examples of Gothic churches exist on the mainland, but during the Renaissance, construction largely consisted of fortifications because of the Ottoman conquest of the hinterland of the region. The most powerful noblemen in the region, the House of Zrinski and the House of Frankopan, built numerous castles in the area. They include the castles of Trsat, Grobnik, Bakar, Kraljevica, Ledenice, Bribir, Hreljin, Grižane, Novi Vinodolski, Krk, Drivenik and Gradec near Vrbnik. The most representative piece of Baroque architecture is the St. Vitus Cathedral in Rijeka.[74]

The region was birthplace or home to several writers who made their marks in Croatian, Italian, and Austrian literature. These include Ivan Mažuranić—one of the foremost authors of Croatian literature in the first half of the 19th century—Janko Polić Kamov, Ödön von Horváth, and many others. Chakavian dialect, spoken in the region, is widely present in the works of poets born or living in the region.[75] The most significant artist from the region is Juraj Julije Klović (Italian: Giorgio Giulio Clovio)—a 16th-century miniaturist, illuminator, and artist born in Grižane in Vinodol. 20th-century artists born or active in the region are Romolo Venucci, Jakov Smokvina, Vladimir Udatny, Antun Haller, Ivo Kalina, Vjekoslav Vojo Radoičić, and many others. Churches and monasteries in the region treasure a great number of works of art. These include a 1535 altar polyptych by Girolamo da Santacroce in the Franciscan monastery on Košljun island, while a Paolo Veneziano polyptych from Benedictine abbey in Jurandvor near Baška is in the collection of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Krk.[76]

Economy

The economy of the Croatian Littoral is largely centered on the city of Rijeka, whose economic impact is felt directly not only in the geographic region, but also in other parts of Primorje-Gorski Kotar County—Gorski Kotar and Liburnia (modern region)—and a substantial part of Lika-Senj County.[77] The most significant economic activities in the Primorje-Gorski Kotar County are transport, largely based on activities of the Port of Rijeka, shipbuilding and tourism in the coastal areas representing a part of the Northern Croatian Littoral, and forestry and wood processing in the Gorski Kotar region in the hinterland.[78] In the city of Rijeka itself, the most significant economic activities are civil engineering, wholesale and retail trade, transport and storage services, and the processing industry.[79] Tourism, wood processing, and agriculture are the predominant economic activities in Lika-Senj County, where nearly all businesses are small and medium enterprisess.[80]

In 2010, two companies headquartered in the Croatian Littoral ranked among the top fifty among Croatian companies by operating income. The highest ranked among them was the Rijeka-based Plodine supermarket chain, which ranked 16th,[82] and Euro Petrol, a petroleum product wholesale and retail company,[83] which ranked 22nd.[84]

| County | GDP | GDP per capita | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| million € | Index (Croatia=100) | € | Index (Croatia=100) | |

| Lika-Senj | 435 | 1.0 | 8,707 | 86.1 |

| Primorje-Gorski Kotar | 3,744 | 8.4 | 12,305 | 121.7 |

| TOTAL: | 4,179 | 9.4 | 12,038 | 119.1 |

| Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics (2008 data)[85] | ||||

Infrastructure

Pan-European transport corridor branch Vb runs through the Croatian Littoral region. The route encompasses the A6 motorway spanning from the Orehovica interchange—part of the Rijeka bypass where the A6 and the A7 motorways meet—to the Bosiljevo 2 interchange, where the corridor route switches to the A1 motorway before proceeding north to Zagreb and Budapest, Hungary. The corridor also comprises a railway line connecting the Port of Rijeka to Zagreb and further destinations abroad.[86] Another significant road transport route in the region is the A7 motorway, connecting Rijeka to Slovenia.[87] The island of Krk is connected to the mainland via the Krk Bridge—comprising a 390-metre (1,280 ft) reinforced concrete arch, the longest in the world when completed in 1980.[88]

The Port of Rijeka is the largest port in Croatia, handling the greatest portion of the country's imports and exports.[89][90] Its facilities include terminals and other structures in the city and in the area reaching from the Bay of Bakar, where the bulk cargo terminal is located, approximately 13 kilometres (8.1 miles) east of Rijeka, to Bršica to the west of Rijeka, where there is a multi-purpose terminal.[91] The Port of Rijeka also serves passenger and ferry lines operated by Jadrolinija to the nearby islands of Cres, Mali Lošinj, Susak, Ilovik, Unije, Rab, and Pag, as well as to Adriatic ports further south, such as Split and Dubrovnik. The line to Split and Dubrovnik also serves the islands of Hvar, Korčula, and Mljet.[92][93] There are two international airports in the region—Rijeka and Lošinj.[94] Both of the airports serve few flights, but the Rijeka Airport is busier of the two.[95]

Pipeline transport infrastructure in the region comprises the Jadranski naftovod (JANAF) pipeline connecting the Omišalj oil terminal—a part of the Port of Rijeka—to Sisak and Virje crude oil storage facilities and terminals and to a terminal in Slavonski Brod further east on the Sava River.[96] JANAF also operates a pipeline between the terminal and the INA's Rijeka Refinery.[97]

See also

References

- 1 2 Lena Mirošević; Branimir Vukosav (June 2010). "Spatial identities of Pag Island and the southern part of the Velebit littoral". Geoadria. University of Zadar, Croatian Geographic Society. 15 (1): 81–108. ISSN 1331-2294. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ↑ Dunja Glogović (June 2003). "Nalazi prapovijesnoga zlata iz Dalmacije i Hrvatskog primorja" [Finds of prehistoric gold in Dalmatia and Croatian Littoral]. Prilozi Instituta za arheologiju u Zagrebu (in Croatian). Institute of Archaeology, Zagreb. 20 (1): 27–32. ISSN 1330-0644. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ↑ Branimir Paškvan (2009). "Smo Primorci ili ... ?" [Are we Primorci or ... ?]. Sušačka Revija (in Croatian). Klub Suščana (68). ISSN 1330-1306. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ↑ "Povijesni pregled" [History overview] (PDF) (in Croatian). Primorje-Gorski Kotar County. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ Ozren Kosanović (November 2009). "Prilog za bibliografiju objavljenih pravnih izvora (statuta, zakona, urbara i notarskih knjiga) i pravnopovijesnih studija za Istru, kvarnersko primorje i otoke u srednjem i ranom novom vijeku" [Contribution to the bibliography of published legal sources (statutes, laws, urbars, and notary books), and related juridico-historical studies for Istria, Kvarner Littoral and its islands in the Middle Ages and Early New Age]. Arhivski vjesnik (in Croatian). Croatian State Archives (52): 129–170. ISSN 0570-9008. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ↑ "Turizam" [Tourism] (in Croatian). Croatian Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 2 May 2006. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- 1 2 "(PRI)LIKA!" [Opportunity/Lika!] (PDF) (in Croatian). United Nations Development Programme in Croatia. 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- 1 2 "Gradovi i općine" [Cities and municipalities] (in Croatian). Primorje-Gorski Kotar County. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Census 2011 First Results". Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 29 June 2011. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ Tari-Kovačić, Vlasta (2002). "Evolution of the northern and western Dinarides: a tectonostratigraphic approach" (PDF). EGU Stephan Mueller Special Publication Series. Copernicus Publications (1): 223–236. ISSN 1868-4556. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ Vlado Kuk; Eduard Prelogović; Ivan Dragičević (December 2000). "Seismotectonically Active Zones in the Dinarides". Geologia Croatica. Croatian Geological Survey. 53 (2): 295–303. ISSN 1330-030X. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ↑ White, William B; Culver, David C, eds. (2012). Encyclopedia of Caves. Academic Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-12-383833-9. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Geographical and Meteorological Data" (PDF). Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Croatia. Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 43: 41. December 2011. ISSN 1333-3305. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ↑ Mate Matas (18 December 2006). "Raširenost krša u Hrvatskoj" [Presence of Karst in Croatia]. geografija.hr (in Croatian). Croatian Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ↑ Siegesmund, Siegfried (2008). Tectonic aspects of the Alpine-Dinaride-Carpathian system. Geological Society. pp. 146–149. ISBN 978-1-86239-252-6. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ↑ Surić, Maša (June 2005). "Submerged Karst – Dead or Alive? Examples from the Eastern Adriatic Coast (Croatia)". Geoadria. University of Zadar. 10 (1): 5–19. ISSN 1331-2294. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ↑ "Otoci" [Islands] (in Croatian). Zadar County Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ↑ Čedomir Benac; Igor Ružić; Elvis Žic (May 2006). "Ranjivost obala u području Kvarnera" [Vulnerability of Kvarner area shores]. Pomorski zbornik (in Croatian). Društvo za proučavanje i unapređenje pomorstva Republike Hrvatske. 44 (1): 201–214. ISSN 0554-6397. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ↑ Mladen Juračić; Čedomir Benac; Ranko Crmarić (December 1999). "Seabed and Surface Sediment Map of the Kvarner Region, Adriatic Sea, Croatia (Lithological Map, 1:500,000)". Geologia Croatica. Croatian Geological Survey. 52 (2): 131–140. ISSN 1330-030X. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- 1 2 "Susak" (in Croatian). peljar.cvs.hr. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

- 1 2 "Ilovik" (in Croatian). peljar.cvs.hr. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

- 1 2 "Vele Srakane" (in Croatian). peljar.cvs.hr. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

- ↑ Duplančić Leder, Tea; Ujević, Tin; Čala, Mendi (June 2004). "Coastline lengths and areas of islands in the Croatian part of the Adriatic Sea determined from the topographic maps at the scale of 1 : 25 000" (PDF). Geoadria. Zadar. 9 (1): 5–32. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ↑ "Cave Srakane". DCS Lošinj. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ↑ "About the county – geographic location". Primorje-Gorski Kotar County. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- ↑ "Obalna razvedenost – Zaljevi i riječna ušća" [Indented coastline – Bays and river confluences] (in Croatian). University of Zadar. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- ↑ Andrija Bognar (November 1994). "Temeljna skica geoloških osobina Velebita" [Basic outline of geological characteristics of Velebit]. Senjski zbornik (in Croatian). Museum of the city of Senj and Senj Museum Society. 21 (1): 1–8. ISSN 0582-673X. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- 1 2 "Regionalni operativni program Primorsko-goranske županije 2008.-2013." [Regional operative plan of the Primorje-Gorski Kotar County 2008–2013] (PDF) (in Croatian). Primorje-Gorski Kotar County. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- ↑ "Grad Rijeka – grad na vodi" [City of Rijeka – a city at the waterfront] (in Croatian). KD Vodovod i Kanalizacija d.o.o. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- ↑ "Geologija – Krš" [Geology – Karst] (in Croatian). Project for Implementation of the Water Framework Directive. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ↑ Tomislav Šegota; Anita Filipčić (June 2003). "Köppenova podjela klima i hrvatsko nazivlje" [Köppen's Classification of Climates and the Croatian Terminology]. Geoadria (in Croatian). University of Zadar, Croatian Geographic Society. 8 (1): 17–37. ISSN 1331-2294. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- 1 2 "Geografski podaci" [Geographic information] (in Croatian). Kvarner tourist board. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- ↑ "Apsolutno najniža temperatura zraka u Hrvatskoj" [The absolute lowest air temperature in Croatia] (in Croatian). Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service. 3 February 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ↑ Cushman-Roisin, Benoit; Gačić, Miroslav; Poulain, Pierre-Marie (2001). Physical oceanography of the Adriatic Sea. Springer. pp. 6–8. ISBN 978-1-4020-0225-0. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ "World Weather Information Service". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ↑ Paul the Deacon (1974). History of the Lombards. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 326–328. ISBN 978-0-8122-1079-8. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ↑ Burns, Thomas S (1991). A history of the Ostrogoths. Indiana University Press. pp. 126–130. ISBN 978-0-253-20600-8. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ↑ Goodrich, Samuel Griswold (1856). A history of all nations, from the earliest periods to the present time. Miller, Orton & Mulligan. p. 773. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ↑ Paton, Andrew Archibald (1861). Researches on the Danube and the Adriatic. Trübner. pp. 218–219. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ↑ Mile Bogović (December 2008). "Senjska glagoljska baština" [Senj glagolitic heritage]. Senjski zbornik (in Croatian). Museum of the city of Senj and Senj Museum Society. 35 (1): 11–26. ISSN 0582-673X. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ↑ Norwich, John Julius (1997). A short history of Byzantium. Knopf. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-679-77269-9. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ↑ Ladislav Heka (October 2008). "Hrvatsko-ugarski odnosi od sredinjega vijeka do nagodbe iz 1868. s posebnim osvrtom na pitanja Slavonije" [Croatian-Hungarian relations from the Middle Ages to the Compromise of 1868, with a special survey of the Slavonian issue]. Scrinia Slavonica (in Croatian). Hrvatski institut za povijest – Podružnica za povijest Slavonije, Srijema i Baranje. 8 (1): 152–173. ISSN 1332-4853. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ↑ Lovorka Čoralić (December 2009). "U okrilju Privedre – Mletačka Republika i hrvatski Jadran" [In Serenissima's realm – Venetian Republic and Croatian Adriatic]. Povijesni prilozi (in Croatian). Hrvatski institut za povijest. 37 (37): 11–40. ISSN 0351-9767. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ↑ "Povijest saborovanja" [History of parliamentarism] (in Croatian). Sabor. Archived from the original on 2 December 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ↑ Richard C. Frucht (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. pp. 422–423. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- 1 2 Ivan Jurišić (October 2005). "Lika i Krbava od Velikog rata za oslobođenje do inkorporacije u Karlovacki generalat (1683–1712)" [Lika and Krbava since the Great War of Liberation until incorporation in Karlovac general command (1683–1712)]. Journal – Institute of Croatian History (in Croatian). Institute of Croatian History, University of Zagreb. 37 (1): 101–110. ISSN 0353-295X. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ↑ Norman Housley (2002). Religious Warfare in Europe, 1400–1536. Oxford University Press. pp. 14–16. ISBN 978-0-19-820811-2. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ↑ Ivo Goldstein (1999). Croatia: A History. C. Hurst & Co. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-1-85065-525-1.

- ↑ Martin, John Jeffries; Romano, Dennis (2002). Venice reconsidered. JHU Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-8018-7308-9. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ↑ Stephens, H Morse (2010). Europe. Forgotten Books. pp. 192, 245. ISBN 978-1-4400-6217-9. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ↑ Grab, Alexander I (2003). Napoleon and the transformation of Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 188–194. ISBN 978-0-333-68274-6. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ↑ Nicolson, Harold (2000). The Congress of Vienna. Grove Press. pp. 180, 226. ISBN 978-0-8021-3744-9. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- 1 2 Oto Luthar (2008). The Land Between: A History of Slovenia. Peter Lang (publishing company). p. 262. ISBN 978-3-631-57011-1. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ↑ Frane Ivković (November 1992). "Organizacija uprave u Dalmaciji za vrijeme druge austrijske vladavine 1814–1918" [Organisation of administration in Dalmatia during the second Austrian reign 1814–1918]. Arhivski vjesnik (in Croatian). Croatian State Archives (34–35): 31–51. ISSN 0570-9008. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ↑ "Riječka luka" [Port of Rijeka] (in Croatian). Museum of the city of Rijeka. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ↑ John R. Lampe; Marvin R. Jackson (1982). Balkan Economic History, 1550–1950: From Imperial Borderlands to Developing Nations. Indiana University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-253-30368-4. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ↑ "Austrijsko primorje" [Austrian Littoral] (in Croatian). Miroslav Krleža Lexicographical Institute. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ↑ "Constitution of Union between Croatia-Slavonia and Hungary". H-net.org. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ↑ Ladislav Heka (December 2007). "Hrvatsko-ugarska nagodba u zrcalu tiska" [Croatian-Hungarian compromise in light of press clips]. Zbornik Pravnog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Rijeci (in Croatian). University of Rijeka. 28 (2): 931–971. ISSN 1330-349X. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ↑ Branko Dubravica (January 2002). "Političko-teritorijalna podjela i opseg civilne Hrvatske u godinama sjedinjenja s vojnom Hrvatskom 1871.-1886." [Political and territorial division and scope of civilian Croatia in period of unification with the Croatian military frontier 1871–1886]. Politička misao (in Croatian). University of Zagreb, Faculty of Political Sciences. 38 (3): 159–172. ISSN 0032-3241. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ↑ "Trianon, Treaty of". The Columbia Encyclopedia. 2009.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer (2005). Encyclopedia of World War I (1 ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 1183. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.

- ↑ Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945. Stanford University Press. pp. 4–16. ISBN 978-0-8047-3615-2. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ↑ Burgwyn, H James (1997). Italian foreign policy in the interwar period, 1918–1940. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 4–16. ISBN 978-0-275-94877-1. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ↑ Lee, Stephen J (2003). Europe, 1890–1945. Routledge. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-415-25455-7. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ↑ D'Agostino, Peter R (2004). Rome in America. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-0-8078-5515-7. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ↑ Singleton, Frederick Bernard (1985). A short history of the Yugoslav peoples. Cambridge University Press. pp. 135–137. ISBN 978-0-521-27485-2. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ↑ Matjaž Klemenčič; Mitja Žagar (2004). The former Yugoslavia's diverse peoples: a reference sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. pp. 153–156, 198–202. ISBN 978-1-57607-294-3. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ↑ Chuck Sudetic (26 June 1991). "2 Yugoslav States Vote Independence To Press Demands". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ↑ "Povijesni pregled" [Historical review] (PDF) (in Croatian). Primorje-Gorski Kotar County. 1997. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ↑ "Cultural heritage on Kvarner". Kvarner Tourist Board. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ "Annual carnival bell ringers' pageant from the Kastav area". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Mirjana Kos-Nalis. "Ethnographic timeline". Kvarner Tourist Board. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Marijan Bradanović; Daina Glavočić. "Architectural heritage". Kvarner Tourist Board. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Velid Đekić. "A reader's guide to Kvarner". Kvarner Tourist Board. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Nataša Šegota Lah. "A panoramic survey of visual arts". Kvarner Tourist Board. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Boris Pirjevec; et al. (May 2004). "Studija o utjecaju na okoliš projekta "Družba Adria"" [Environmental impact assessment for the "Druzhba Adria" project] (PDF) (in Croatian). Zagreb: Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Zagreb. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ↑ "Gospodarski profil županije" [Economic profile of the county] (in Croatian). Croatian Chamber of Economy. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ "Riječko gospodarstvo – trendovi i perspektive" [Economy of Rijeka – trends and the future] (in Croatian). City of Rijeka. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ "Gospodarski profil županije" [Economic profile of the county] (in Croatian). Croatian Chamber of Economy. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ Ana Raić Knežević (13 December 2011). "Talijanski jahtaši sele se u hrvatske marine" [Italian yachts move to Croatia]. Novi list (in Croatian). Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ "O nama" [About us] (in Croatian). Plodine. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ "O nama" [About us] (in Croatian). Euro Petrol. Archived from the original on 6 June 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ "Rang-ljestvica 400 najvećih" [Ranking of the top 400]. Privredni vjesnik (in Croatian). Croatian Chamber of Economy. 58 (3687): 38–50. July 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ↑ "Gross domestic product for Republic of Croatia, statistical regions at level 2 and counties, 2008". Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 11 February 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ↑ "Transport : launch of the Italy-Turkey pan-European Corridor through Albania, Bulgaria, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Greece". European Union. 9 September 2002. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ↑ "Pravilnik o označavanju autocesta, njihove stacionaže, brojeva izlaza i prometnih čvorišta te naziva izlaza, prometnih čvorišta i odmorišta" [Regulation on motorway markings, chainage, interchange/exit/service area numbers and names]. Narodne novine (in Croatian). 6 May 2003. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ Veselin Simović (September 2000). "Dvadeseta obljetnica mosta kopno – otok Krk" [Twentieth anniversary of the Krk – mainland bridge]. Građevinar (in Croatian). Croatian association of civil engineers. 52 (8): 431–442. ISSN 0350-2465. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ↑ "Riječka luka –jadranski "prolaz" prema Europi" [The Port of Rijeka – Adriatic "gateway" to Europe] (in Croatian). World Bank. 3 March 2006. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ↑ Čedomir Dundović; Bojan Hlača (2007). "New Concept of the Container Terminal in the Port of Rijeka". Pomorstvo. University of Rijeka, Faculty of Maritime Studies. 21 (2): 51–68. ISSN 1332-0718. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ↑ "Terminals". Luka Rijeka d.d. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ↑ "TABULAR PRESENTATION OF THE TIMETABLE FROM 01.01.2011 TILL 31 December 2011". Jadrolinija. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ↑ "Plovidbeni red za 2011. godinu" [Sailing Schedule for Year 2011] (in Croatian). Agencija za obalni linijski pomorski promet. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ↑ "Popis registriranih aerodroma u Republici Hrvatskoj" [List of registered airports in the Republic of Croatia] (PDF) (in Croatian). Croatian Civil Aviation Agency. 2 May 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ "Promet u zračnim lukama u srpnju 2011." [Airport traffic in July 2011]. Priopćenje Državnog zavoda za statistiku Republike Hrvatske (in Croatian). Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 48 (5.1.5/7.). 9 September 2011. ISSN 1330-0350. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ "The JANAF system". Jadranski naftovod. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ↑ "Iskrcavanje nafte na Urinju prijeti Kvarneru" [Transshipment of oil at Urinj threatens Kvarner] (in Croatian). limun.hr. 3 February 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

External links

Coordinates: 44°55′52″N 14°55′08″E / 44.931°N 14.919°E