Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

| Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease | |

|---|---|

| |

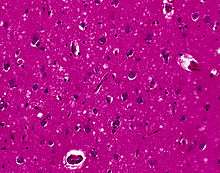

| Biopsy of the tonsil in variant CJD. Prion protein immunostaining. | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Neurology, Psychiatry |

| Symptoms |

Early: memory problems, behavioral changes, poor coordination, visual disturbances[2] Later: dementia, involuntary movements, blindness, weakness, coma[2] |

| Usual onset | Around 60[2] |

| Types | Sporadic, hereditary, acquired[2] |

| Causes | Prion[2] |

| Diagnostic method | After ruling out other possible causes[2] |

| Similar conditions | Encephalitis, chronic meningitis, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer's disease[2] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[2] |

| Prognosis | 90% die within a year of diagnosis[2] |

| Frequency | 1 per million per year[2] |

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) is a universally fatal brain disorder.[2] Early symptoms include memory problems, behavioral changes, poor coordination, and visual disturbances.[2] Later dementia, involuntary movements, blindness, weakness, and coma occur.[2] About 90% of people die within a year of diagnosis.[2]

CJD is believed to be caused by a protein known as a prion.[2] Infectious prions are misfolded proteins that can cause normally folded proteins to become misfolded.[2] Most cases occur spontaneously, while about 7.5% of cases are inherited from a person's parents in an autosomal dominant manner.[2] Exposure to brain or spinal tissue from an infected person may also result in spread.[2] There is no evidence that it can spread between people via normal contact or blood transfusions.[2] Diagnosis involves ruling out other potential causes.[2] An electroencephalogram, spinal tap, or magnetic resonance imaging may support the diagnosis.[2]

There is no specific treatment.[2] Opioids may be used to help with pain, while clonazepam or sodium valproate may help with involuntary movements.[2] CJD affects about one per million people per year.[2] Onset is typically around 60 years of age.[2] The condition was first described in 1920.[2] It is classified as a type of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy.[3] CJD is different from bovine spongiform encephalopathy (mad cow disease) and variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD).[4]

Classification

Types of CJD include:[5]

- sporadic (sCJD), caused by the spontaneous misfolding of prion-protein in an individual.[6] This accounts for 85% of cases of CJD.[7]

- familial (fCJD), caused by an inherited mutation in the prion-protein gene.[5] This accounts for the majority of the other 15% of cases of CJD.[7]

- acquired CJD, caused by contamination with tissue from an infected person, usually as the result of a medical procedure (iatrogenic CJD). Medical procedures that are associated with the spread of this form of CJD include blood transfusion from the infected person, use of human-derived pituitary growth hormones, gonadotropin hormone therapy, and corneal and meningeal transplants.[5][7][8]

Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) is a different condition which is potentially acquired from Bovine spongiform encephalopathy or caused by consuming food contaminated with prions.[5]

Signs and symptoms

The first symptom of CJD is usually rapidly progressive dementia, leading to memory loss, personality changes, and hallucinations. Myoclonus (jerky movements) typically occurs in 90% of cases, but may be absent at initial onset.[9] Other frequently occurring features include anxiety, depression, paranoia, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and psychosis.[10] This is accompanied by physical problems such as speech impairment, balance and coordination dysfunction (ataxia), changes in gait, rigid posture, and seizures. In most patients, these symptoms are accompanied by involuntary movements and the appearance of an atypical, diagnostic electroencephalogram tracing. The duration of the disease varies greatly, but sporadic (non-inherited) CJD can be fatal within months or even weeks.[11] Most victims die six months after initial symptoms appear, often of pneumonia due to impaired coughing reflexes. About 15% of patients survive for two or more years.[12]

The symptoms of CJD are caused by the progressive death of the brain's nerve cells, which is associated with the build-up of abnormal prion protein molecules forming amyloids. When brain tissue from a CJD patient is examined under a microscope, many tiny holes can be seen where whole areas of nerve cells have died. The word "spongiform" in "transmissible spongiform encephalopathies" refers to the sponge-like appearance of the brain tissue.

Cause

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy diseases are caused by prions. Prions are proteins that occur normally in neurons of the central nervous system (CNS). These proteins are thought to affect signaling processes, damaging neurons and resulting in degeneration that causes the spongiform appearance in the affected brain.[13]

The CJD prion is dangerous because it promotes refolding of native prion protein into the diseased state.[14] The number of misfolded protein molecules will increase exponentially and the process leads to a large quantity of insoluble protein in affected cells. This mass of misfolded proteins disrupts neuronal cell function and causes cell death. Mutations in the gene for the prion protein can cause a misfolding of the dominantly alpha helical regions into beta pleated sheets. This change in conformation disables the ability of the protein to undergo digestion. Once the prion is transmitted, the defective proteins invade the brain and induce other prion protein molecules to misfold in a self-sustaining feedback loop. These neurodegenerative diseases are commonly called prion diseases.

People can also develop CJD because they carry a mutation of the gene that codes for the prion protein (PRNP). This occurs in only 5-10% of all CJD cases. In sporadic cases the misfolding of the prion protein probably occurs as a natural, spontaneous process.[6] An EU study determined that "87% of cases were sporadic, 8% genetic, 5% iatrogenic and less than 1% variant."[15]

Transmission

The defective protein can be transmitted by contaminated harvested human brain products, corneal grafts,[16] dural grafts,[17] or electrode[18] implants and human growth hormone[19]

It can be familial (fCJD); or it may appear without risk factors (sporadic form: sCJD). In the familial form, a mutation has occurred in the gene for PrP, PRNP, in that family. All types of CJD are transmissible irrespective of how they occur in the patient.[20]

It is thought that humans can contract the disease by consuming material from animals infected with the bovine form of the disease.[21]

Cannibalism has also been implicated as a transmission mechanism for abnormal prions, causing the disease known as kuru, once found primarily among women and children of the Fore people in Papua New Guinea.[22] While the men of the tribe ate the body of the deceased and rarely contracted the disease, the women and children, who ate the less desirable body parts, including the brain, were eight times more likely than men to contract kuru from infected tissue.

Prions, the infectious agent of CJD, may not be inactivated by means of routine surgical instrument sterilization procedures. The World Health Organization and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that instrumentation used in such cases be immediately destroyed after use; short of destruction, it is recommended that heat and chemical decontamination be used in combination to process instruments that come in contact with high-infectivity tissues. No cases of iatrogenic transmission of CJD have been reported subsequent to the adoption of current sterilization procedures, or since 1976.[23][24][25] Copper-hydrogen peroxide has been suggested as an alternative to the current recommendation of sodium hydroxide or sodium hypochlorite.[26] Thermal depolymerization also destroys prions in infected organic and inorganic matter, since the process chemically attacks protein at the molecular level, although more effective and practical methods involve destruction by combinations of detergents and enzymes similar to biological washing powders.[27]

Blood products

In 2004, a report published in the Lancet medical journal showed that vCJD can be transmitted by blood transfusions.[28] The finding alarmed healthcare officials because a large epidemic of the disease could result in the near future. A blood test for vCJD infection is possible[29] but is not yet available for screening blood donations. Significant restrictions exist to protect the blood supply. The UK government banned anyone who had received a blood transfusion since January 1980 from donating blood.[30] From 1999 there has been a ban in the UK for using UK blood to manufacture fractional products such as albumin.[31] Whilst these restrictions may go some way to preventing a self-sustaining epidemic of secondary infections the number of infected blood donations is unknown and could be considerable as a study by the Health Protection Agency show around 1 in 2000 people in the UK shows signs of abnormal prion accumulation.[32] In June 2013 the government was warned that deaths—then at 176—could rise five-fold through blood transfusions.[33]

On May 28, 2002, the United States Food and Drug Administration instituted a policy that excludes from donation anyone having spent at least six months in certain European countries (or three months in the United Kingdom) from 1980 to 1996. Given the large number of U.S. military personnel and their dependents residing in Europe, it was expected that over 7% of donors would be deferred due to the policy. Later changes to this policy have relaxed the restriction to a cumulative total of five years or more of civilian travel in European countries (six months or more if military). The three-month restriction on travel to the UK, however, has not been changed.[34]

The American Red Cross' policy is as follows: During the period January 1, 1980, to December 31, 1996, spending a total time of three months or more in the United Kingdom, Channel Islands, the Falkland Islands and Gibraltar precludes individuals from donating. Moreover, spending a total time of five years or more after January 1, 1980 (to present), in the above-mentioned countries and/or any country in Europe (except the former USSR), also precludes donation. People with a biologic relative having been diagnosed with CJD or vCJD are unable to donate. Biologic relative in this setting means mother, father, sibling, grandparent, aunt, uncle, or child.

A similar policy applies to potential donors to the Australian Red Cross Blood Service, precluding people who have spent a cumulative time of six months or more in the United Kingdom between 1980 and 1996.

The Singapore Red Cross precludes potential donors having spent a cumulative time of three months or more in the United Kingdom between 1980 and 1996.

In New Zealand, the New Zealand Blood Service (NZBS) in 2000 introduced measures to preclude permanently donors having resided in the United Kingdom (including the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands) for a total of six months or more between January 1980 and December 1996. The measure resulted in ten percent of New Zealand's active blood donors at the time becoming ineligible to donate blood. In 2003, the NZBS further extended restrictions to preclude permanently donors having had received a blood transfusion in the United Kingdom since January 1980, and in April 2006, restrictions were further extended to include the Republic of Ireland and France.[35]

Similar regulations are in place in France and in Germany, where anyone having spent six months or more living in the UK between January 1980 and December 1996 is permanently banned from donating blood.[36]

In Canada, individuals are not eligible to donate blood or plasma if they have spent a cumulative total of three months or more in the United Kingdom (UK) or France from January 1, 1980, to December 31, 1996. They are also ineligible if they have spent a cumulative total of five years or more in Western Europe outside the U.K. or France since January 1, 1980 through December 31, 2007 or Spent a cumulative total of six months or more in Saudi Arabia from January 1, 1980 through December 31, 1996[37] or if they have had a blood transfusion in the U.K., France or Western Europe since 1980.[38]

The Association of Blood Donors of Denmark precludes potential donors having spent a cumulative time of at least 12 months in the United Kingdom between 1 January 1980 and 31 December 1996.

The Swiss Blutspendedienst SRK precludes potential donors having spent a cumulative time of at least six months in the United Kingdom between 1 January 1980 and 31 December 1996.

In Poland, anyone having spent cumulatively six months or longer between 1 January 1980 and 31 December 1996 in the UK, Ireland, or France is permanently barred from donating.[39]

In the Czech Republic, anyone having spent more than six months in the UK or France between the years 1980 and 1996 or received transfusion in the UK after the year 1980 is not allowed to donate blood.[40] In South Korea, anyone having spent more than three months in the UK after 1997, or more than a month between 1980 and 1996 is banned from donating blood.

Sperm donation

In the U.S., the FDA has banned import of any donor sperm, motivated by a risk of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, inhibiting the once popular[41] import of Scandinavian sperm. Despite this the scientific consensus is that the risk is negligible, as there is no evidence Creutzfeldt–Jakob is sexually transmitted.[42] [43] [44]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CJD is suspected when there are typical clinical symptoms and signs such as rapidly progressing dementia with startle myoclonus.[45] Further investigation can then be performed to support the diagnosis including

- Electroencephalography—often has characteristic generalized periodic sharp wave pattern (~80% of pts by 6 months)

- Cerebrospinal fluid analysis for 14-3-3 protein

- MRI of the brain—often shows high signal intensity in the caudate nucleus and putamen bilaterally on T2-weighted images.

- Research in 2010 and 2011 identified a possible blood test for CJD. The test attempts to identify the prion responsible for the disease. However, it has not yet been demonstrated if it is able to detect the prions in early stages of the disease.[46]

Diffusion Weighted Imaging (DWI) images are the most sensitive. In about 24% of cases DWI shows only cortical hyperintensity; in 68%, cortical and subcortical abnormalities; and in 5%, only subcortical anomalies.[47] The involvement of the thalamus can be found in sCJD, is even stronger and constant in vCJD.[48]

Clinical testing for CJD has always been an issue. Diagnosis has been based mostly on clinical and physical examination of symptoms. In recent years, studies have shown that the tumour marker Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) is often elevated in CJD cases, however its diagnostic utility is seen primarily when combined with a test for the 14-3-3 protein.[49] As of 2010, screening tests to identify infected asymptomatic individuals, such as blood donors, are not yet available, though methods have been proposed and evaluated.[50]

In 2010, a team from New York described detection of PrPSc even when initially present at only one part in one hundred billion (10−11) in brain tissue. The method combines amplification with a novel technology called surround optical fiber immunoassay (SOFIA) and some specific antibodies against PrPSc. After amplifying and then concentrating any PrPSc, the samples are labelled with a fluorescent dye using an antibody for specificity and then finally loaded into a micro-capillary tube. This tube is placed in a specially constructed apparatus so that it is totally surrounded by optical fibres to capture all light emitted once the dye is excited using a laser. The technique allowed detection of PrPSc after many fewer cycles of conversion than others have achieved, substantially reducing the possibility of artefacts, as well as speeding up the assay. The researchers also tested their method on blood samples from apparently healthy sheep that went on to develop scrapie. The animals’ brains were analysed once any symptoms became apparent. The researchers could therefore compare results from brain tissue and blood taken once the animals exhibited symptoms of the diseases, with blood obtained earlier in the animals’ lives, and from uninfected animals. The results showed very clearly that PrPSc could be detected in the blood of animals long before the symptoms appeared. After further development and testing, this method could be of great value in surveillance as a blood or urine-based screening test for CJD.[51][52] In 2014, a human study showed a nasal brushing method that can accurately detect PrP in the olfactory epithelial of CJD patients. .[53] This finding creates new opportunities for minimally invasive detection of CJD.

In one-third of patients with sporadic CJD, deposits of "prion protein (scrapie)," PrPSc, can be found in the skeletal muscle and/or the spleen. Diagnosis of vCJD can be supported by biopsy of the tonsils, which harbour significant amounts of PrPSc; however, biopsy of brain tissue is the definitive diagnostic test for all other forms of prion disease. Due to its invasiveness, biopsy will not be done if clinical suspicion is sufficiently high or low. A negative biopsy does not rule out CJD, since it may predominate in a specific part of the brain.[54]

The classic histologic appearance is spongiform change in the gray matter: the presence of many round vacuoles from one to 50 micrometres in the neuropil, in all six cortical layers in the cerebral cortex or with diffuse involvement of the cerebellar molecular layer.[55] These vacuoles appear glassy or eosinophilic and may coalesce. Neuronal loss and gliosis are also seen.[56] Plaques of amyloid-like material can be seen in the neocortex in some cases of CJD.

However, extra-neuronal vacuolization can also be seen in other disease states. Diffuse cortical vacuolization occurs in Alzheimer's disease, and superficial cortical vacuolization occurs in ischemia and frontotemporal dementia. These vacuoles appear clear and punched-out. Larger vacuoles encircling neurons, vessels, and glia are a possible processing artifact.[54]

- Clinical and Pathologic Characteristics:[57]

| Characteristic | Classic CJD | Variant CJD |

|---|---|---|

| Median age at death | 68 years | 28 years |

| Median duration of illness | 4–5 months | 13–14 months |

| Clinical signs and symptoms | Dementia; early neurologic signs | Prominent psychiatric/behavioral symptoms; painful dysesthesias;

delayed neurologic signs |

| Periodic sharp waves on electroencephalogram | Often present | Often absent |

| Signal hyperintensity in the caudate nucleus and putamen on diffusion-weighted and FLAIR MRI | Often present | Often absent |

| Pulvinar sign-bilateral high signal intensities on axial fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI. Also posterior thalami involvement on sagittal T2 sequences | Not reported | Present in >75% of cases |

| Immunohistochemical analysis of brain tissue | Variable accumulation. | Marked accumulation of protease-resistant prion protein |

| Presence of agent in lymphoid tissue | Not readily detected | Readily detected |

| Increased glycoform ratio on immunoblot analysis of

protease-resistant prion protein |

Not reported | Marked accumulation of protease-resistant prion protein |

| Presence of amyloid plaques in brain tissue | May be present | May be present |

- An abnormal signal in the posterior thalamus on T2- and diffusion-weighted images and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); in the appropriate clinical context, this signal is highly specific for vCJD. (Source: CDC)

Treatment

As of 2015 there was no cure for BSE; some of the symptoms like twitching can be managed but otherwise treatment is palliative care.[58]

Outcomes

The condition is fatal. Cases where people live up to 2.5 years have been described.[59]

Epidemiology

Although CJD is the most common human prion disease, it is still believed to be rare, estimated to occur in about one out of every one million people every year, however, an autopsy study published in 1989 and others suggest that between 3-13% of people diagnosed with Alzheimer's were actually misdiagnosed, and instead had CJD, not alzheimers.[60] Presumably the people became infected through prion contaminated beef from cattle with subclinical atypical BSE, which has a very long incubation period. CJD usually affects people aged 45–75, most commonly appearing in people between the ages of 60–65. The exception to this is the more recently recognised 'variant' CJD (vCJD), which occurs in younger people.

CDC monitors the occurrence of CJD in the United States through periodic reviews of national mortality data. According to the CDC:

- CJD occurs worldwide at a rate of about 1 case per million population per year.

- On the basis of mortality surveillance from 1979 to 1994, the annual incidence of CJD remained stable at approximately 1 case per million people in the United States.

- In the United States, CJD deaths among people younger than 30 years of age are extremely rare (fewer than five deaths per billion per year[61][62]).

- The disease is found most frequently in patients 55–65 years of age, but cases can occur in people older than 90 years and younger than 55 years of age.

- In more than 85% of cases, the duration of CJD is less than 1 year (median: four months) after onset of symptoms.[61][62]

Additional concerns

The Lancet in 2006 suggested that it may take more than 50 years for vCJD to develop, from their studies of kuru, a similar disease in Papua New Guinea.[63] The reasoning behind the claim is that kuru was possibly transmitted through cannibalism in Papua New Guinea when family members would eat the body of a dead relative as a sign of mourning. In the 1950s, cannibalism was banned in Papua New Guinea.[64] In the late 20th century, however, kuru reached epidemic proportions in certain Papua New Guinean communities, therefore suggesting that vCJD may also have a similar incubation period of 20 to 50 years. A critique to this theory is that while mortuary cannibalism was banned in Papua New Guinea in the 1950s, that does not necessarily mean that the practice ended. 15 years later Jared Diamond was informed by Papuans that the practice continued.[64] Kuru may have passed to the Fore people through the preparation of the dead body for burial.

These researchers noticed a genetic variation in some kuru patients that has been known to promote long incubation periods. They have also proposed that individuals having contracted CJD in the early 1990s represent a distinct genetic subpopulation, with unusually short incubation periods for bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). This means that there may be many more vCJD patients with longer incubation periods, which may surface many years later.[63]

In 1997, a number of people from Kentucky, US, developed CJD. It was discovered that all the victims had consumed squirrel brains, although a coincidental relationship between the disease and this dietary practice may have been involved.[65] In 2008, UK scientists expressed concern over the possibility of a second wave of human cases due to the wide exposure and long incubation of some cases of vCJD.[66]

Prion protein is detectable in lymphoid and appendix tissue up to two years before the onset of neurological symptoms in vCJD. Large scale studies in the UK have yielded an estimated prevalence of 493 per million, higher than the actual number of reported cases. This finding indicates a large number of asymptomatic cases and the need to monitor.[67]

History

The disease was first described by German neurologist Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt in 1920 and shortly afterward by Alfons Maria Jakob, giving it the name Creutzfeldt–Jakob. Some of the clinical findings described in their first papers do not match current criteria for Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, and it has been speculated that at least two of the patients in initial studies were suffering from a different ailment.[68] An early description of familial CJD stems from the German psychiatrist and neurologist Friedrich Meggendorfer (1880–1953).[69][70] A study published in 1997 counted more than 100 cases worldwide of transmissible CJD and new cases continued to appear at the time.[71]

The first report of suspected iatrogenic CJD was published in 1974. Animal experiments showed that corneas of infected animals could transmit CJD, and the causative agent spreads along visual pathways. A second case of CJD associated with a corneal transplant was reported without details. In 1977, CJD transmission caused by silver electrodes previously used in the brain of a person with CJD was first reported. Transmission occurred despite decontamination of the electrodes with ethanol and formaldehyde. Retrospective studies identified four other cases likely of similar cause. The rate of transmission from a single contaminated instrument is unknown, although it is not 100%. In some cases, the exposure occurred weeks after the instruments were used on a person with CJD.[71]

A review article published in 1979 indicated that 25 dura mater cases had occurred by that date in Australia, Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[71]

By 1985, a series of case reports in the United States showed that when injected, cadaver-extracted pituitary human growth hormone could transmit CJD to humans.[71]

In 1992, it was recognized that human gonadotropin administered by injection could also transmit CJD from person to person.[71]

In 2004, a report published by Edinburgh doctors in the Lancet medical journal demonstrated that vCJD was transmitted by blood transfusion.[28]

Stanley B. Prusiner of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) was awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 1997 "for his discovery of Prions—a new biological principle of infection".[72] However, Yale University neuropathologist Laura Manuelidis has challenged the prion protein (PrP) explanation for the disease. In January 2007, she and her colleagues reported that they had found a virus-like particle in naturally and experimentally infected animals. "The high infectivity of comparable, isolated virus-like particles that show no intrinsic PrP by antibody labeling, combined with their loss of infectivity when nucleic acid–protein complexes are disrupted, make it likely that these 25-nm particles are the causal TSE virions".[73]

Australia

Four Australians had been reported with CJD following transfusion as of 1997.[71] There have been ten cases of healthcare-acquired CJD in Australia. They consist of five deaths following treatment with pituitary extract hormone for either infertility or short stature, with no further cases since 1991. The five other deaths were caused by dura grafting during brain surgery, where the covering of the brain was repaired. There have been no other known healthcare-acquired CJD deaths in Australia.[74]

New Zealand

A case was reported in 1989 in a 25-year-old man from New Zealand, who also received dura mater transplant.[71] Five New Zealanders have been confirmed to have died of the sporadic form of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) in 2012.[75]

United Kingdom

Researchers believe one in 2,000 people in the UK is a carrier of the disease linked to eating contaminated beef (vCJD).[76] The survey provides the most robust prevalence measure to date—and identifies abnormal prion protein across a wider age group than found previously and in all genotypes, indicating "infection" may be relatively common. This new study examined over 32,000 anonymous appendix samples. Of these, 16 samples were positive for abnormal prion protein, indicating an overall prevalence of 493 per million population, or one in 2,000 people are likely to be carriers. No difference was seen in different birth cohorts (1941–60 and 1961–85), in both sexes, and there was no apparent difference in abnormal prion prevalence in three broad geographical areas. Genetic testing of the 16 positive samples revealed a higher proportion of valine homozygous (VV) genotype on the codon 129 of the gene encoding the prion protein (PRNP) compared with the general UK population. This also differs from the 177 patients with vCJD, all of whom to date have been methionine homozygous (MM) genotype. The concern is that individuals with this VV genotype may be susceptible to developing the condition over longer incubation periods.[77]

United States

In 1988, there was a confirmed death from CJD of a person from Manchester, New Hampshire. Massachusetts General Hospital believed the patient acquired the disease from a surgical instrument at a podiatrist's office. In September 2013, another patient in Manchester was posthumously determined to have died of the disease. The patient had undergone brain surgery at Catholic Medical Center three months before his death, and a surgical probe used in the procedure was subsequently reused in other operations. Public health officials identified thirteen patients at three hospitals who may have been exposed to the disease through the contaminated probe, but said the risk of anyone's contracting CJD is "extremely low."[78][79][80] In January 2015, the former speaker of the Utah House of Representatives, Rebecca D. Lockhart, died of the disease within a few weeks of diagnosis.[81] John Carroll, former editor of The Baltimore Sun and Los Angeles Times, died of CJD in Kentucky in June 2015, after having been diagnosed in January.[82] American actress Barbara Tarbuck (General Hospital, American Horror Story) died of the disease on December 26, 2016.[83]

Research

An experimental treatment was given to a Northern Irish teenager, Jonathan Simms, beginning in January 2003.[84] The medication, called pentosan polysulphate (PPS) and used to treat interstitial cystitis, is infused into the patient's lateral ventricle within the brain. PPS does not seem to stop the disease from progressing, and both brain function and tissue continue to be lost. However, the treatment is alleged to slow the progression of the otherwise untreatable disease, and may have contributed to the longer than expected survival of the seven patients studied.[85] Simms died in 2011.[86] The CJD Therapy Advisory Group to the UK Health Departments advises that data are not sufficient to support claims that pentosan polysulphate is an effective treatment and suggests that further research in animal models is appropriate.[87] A 2007 review of the treatment of 26 patients with PPS finds no proof of efficacy because of the lack of accepted objective criteria.[88]

Scientists have investigated using RNA interference to slow the progression of scrapie in mice. The RNA blocks production of the protein that the CJD process transforms into prions. This research is unlikely to lead to a human therapy for many years.[89]

Both amphotericin B and doxorubicin have been investigated as potentially effective against CJD, but as yet there is no strong evidence that either drug is effective in stopping the disease. Further study has been taken with other medical drugs, but none are effective. However, anticonvulsants and anxiolytic agents, such as valproate or a benzodiazepine, may be administered to relieve associated symptoms.[12]

Scientists from the University of California, San Francisco are currently running a treatment trial for sporadic CJD using quinacrine, a medicine originally created for malaria. Pilot studies showed quinacrine permanently cleared abnormal prion proteins from cell cultures, but results have not yet been published on their clinical study. The efficacy of quinacrine was also assessed in a rigorous clinical trial in the UK and the results were published in Lancet Neurology,[90] and concluded that quinacrine had no measurable effect on the clinical course of CJD.

In a 2013 paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, scientists from The Scripps Research Institute reported that Astemizole, a medication approved for human use, has been found to have anti-prion activity and may lead to a treatment for Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease.[91]

See also

References

- ↑ Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 "Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Fact Sheet | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". NINDS. March 2003. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ "About CJD | Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Classic (CJD) | Prion Disease". CDC. 11 February 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ "Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Classic (CJD) | Prion Diseases". CDC. 6 February 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Budka, H; Will, RG (12 November 2015). "The end of the BSE saga: do we still need surveillance for human prion diseases?". Swiss medical weekly. 145: w1421 2. PMID 26715203. doi:10.4414/smw.2015.14212.

- 1 2 Ridley, R.M., Baker, H.F. and Crow, T.J. (1986). "Transmissible and non-transmissible dementia: similarities in age of onset and genetics in relation to aetiology.". Psychological Medicine. 16: 199–207. doi:10.1017/s0033291700002634.

- 1 2 3 who.int: "Fact sheets no 180: Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease" Feb 2012 ed.

- ↑ Bonda, DJ; Manjila, S; Mehndiratta, P; Khan, F; Miller, BR; Onwuzulike, K; Puoti, G; Cohen, ML; Schonberger, LB; Cali, I (July 2016). "Human prion diseases: surgical lessons learned from iatrogenic prion transmission.". Neurosurgical focus. 41 (1): E10. PMC 5082740

. PMID 27364252. doi:10.3171/2016.5.FOCUS15126.

. PMID 27364252. doi:10.3171/2016.5.FOCUS15126. - ↑ "A 49-Year-Old Man With Forgetfulness and Gait Impairment". http://reference.medscape.com/viewarticle/881806_3. Retrieved 2017-07-09. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Murray ED, Buttner N, Price BH. (2012) Depression and Psychosis in Neurological Practice. In: Neurology in Clinical Practice, 6th Edition. Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J (eds.) Butterworth Heinemann. April 12, 2012. ISBN 1437704344 | ISBN 978-1437704341

- ↑ Brown, P; et al. (1986). "Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: clinical analysis of a consecutive series of 230 neuropathologically verified cases". Ann. Neurol. 20: 597–602. doi:10.1002/ana.410200507.

- 1 2 Gambetti, Pierluigi. "Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease (CJD)". The Merck Manuals: Online Medical Library. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ Sattar, Husain A. Fundamentals of Pathology. p. 189.

- ↑ Clarke, AR; Jackson, GS; Collinge, J (Feb 28, 2001). "The molecular biology of prion propagation". Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 356 (1406): 185–95. PMC 1088424

. PMID 11260799. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0764.

. PMID 11260799. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0764. - ↑ Will, R. G.; Alperovitch, A.; Poser, S.; Pocchiari, M.; Hofman, A.; Mitrova, E.; de Silva, R.; D'Alessandro, M.; Delasnerie-Laupretre, N.; Zerr, I.; van Duijn, C. (1998). "EU collaborative Study Group for CJD (1998), Descriptive epidemiology of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in six european countries, 1993–1995". Annals of Neurology. 43: 763–767. doi:10.1002/ana.410430611.

- ↑ Armitage, W J; Tullo, A B; Ironside, J W (9 January 2009). "Risk of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease transmission by ocular surgery and tissue transplantation". Eye. 23 (381): 1928. doi:10.1038/eye.2008.381. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ↑ Esmonde, T; et al. (1993). "Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and lyophilised dura mater grafts: report of two cases". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 56: 999–1000. doi:10.1136/jnnp.56.9.999.

- ↑ Bernoulli, C; et al. (1977). "Danger of accidental person-to-person transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease by surgery.". Lancet. i: 478–479. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91958-4.

- ↑ Brown, P; et al. (2012). "Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, final assessment". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 18: 901–907. doi:10.3201/eid1806.120116.

- ↑ Brown, P; et al. "Human spongiform encephalopathy: the National Institutes of Health series of 300 cases of experimentally transmitted disease". Ann. Neurol. 35: 513–529. doi:10.1002/ana.410350504.

- ↑ Collinge, J; Sidle, KC; Meads, J; Ironside, J; Hill, AF (Oct 24, 1996). "Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of 'new variant' CJD". Nature. 383 (6602): 685–90. PMID 8878476. doi:10.1038/383685a0.

- ↑ Collinge, J; et al. (2006). "Kuru in the 21st century--an acquired human prion disease with very long incubation periods". Lancet. 367: 2068–2074. PMID 16798390. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68930-7.

- ↑ "Questions and Answers: Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease Infection-Control Practices". Infection Control Practices/CJD (Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease, Classic). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. January 4, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ↑ "WHO Infection Control Guidelines for Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies". World Health Organization: Communicable Disease Surveillance and Control. 26 March 1999. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ↑ McDonnell G, Burke P (May 2003). "The challenge of prion decontamination". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 36 (9): 1152–4. PMID 12715310. doi:10.1086/374668.

- ↑ Solassol J, Pastore M, Crozet C (2006). "A novel copper-hydrogen peroxide formulation for prion decontamination". J Infect Dis. 194 (6): 865–869. PMID 16941355. doi:10.1086/506947.

- ↑ Jackson, GS; McKintosh, E; Flechsig, E; Prodromidou, K; Hirsch, P; Linehan, J; Brandner, S; Clarke, AR; Weissmann, C; Collinge, J (March 2005). "An enzyme-detergent method for effective prion decontamination of surgical steel". The Journal of general virology. 86 (Pt 3): 869–78. PMID 15722550. doi:10.1099/vir.0.80484-0.

- 1 2 Peden AH, Head MW, Ritchie DL, Bell JE, Ironside JW (2004). "Preclinical vCJD after blood transfusion in a PRNP codon 129 heterozygous patient". Lancet. 364 (9433): 527–9. PMID 15302196. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16811-6.

- ↑ Edgeworth, JA; Farmer, M; Sicilia, A; Tavares, P; Beck, J; Campbell, T; Lowe, J; Mead, S; Rudge, P; Collinge, J; Jackson, GS (Feb 5, 2011). "Detection of prion infection in variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: a blood-based assay". Lancet. 377 (9764): 487–93. PMID 21295339. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62308-2.

- ↑ "Variant CJD and blood donation" (PDF). National Blood Service. August 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 11, 2007. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ Regan F, Taylor C (July 2002). "Blood transfusion medicine". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 325 (7356): 143–7. PMC 1123672

. PMID 12130612. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7356.143.

. PMID 12130612. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7356.143. - ↑ HPA Press Office (August 10, 2012). "Summary results of the second national survey of abnormal prion prevalence in archived appendix specimens".

- ↑ Rowena Mason (April 28, 2013). "Mad cow infected blood 'to kill 1,000'". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- ↑ "In-Depth Discussion of Variant Creutzfeld–Jacob Disease and Blood Donation". American Red Cross. Archived from the original on 2007-12-30. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ "CJD (Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease) - Information for blood donors" (PDF). New Zealand Blood Service. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ↑ "Permanent exclusion criteria" (in German). Blutspendedienst Hamburg. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 2009-06-20. English via Google Translate

- ↑ "Canada restricts blood donors from Saudi Arabia". ctv news. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Travel restrication". Canadian Blood Services. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Permanent exclusion criteria / Dyskwalifikacja stała" (in Polish). RCKiK Warszawa. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- ↑ "Blood donor guidance / Poučení dárce krve" (in Czech). Fakultní nemocnice Královské Vinohrady. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ↑ Stein, Rob (August 13, 2008). "Mad Cow Rules Hit Sperm Banks' Patrons". washingtonpost.com. The Washington Post Company. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- ↑ Kotler, Steven (2007-09-27). "The God of Sperm". LA Weekly. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ "Is there a real risk of transmitting variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease by donor sperm insemination?". Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 2006. Retrieved 2017-01-07.

- ↑ Lapidos, Juliet (2007-09-26). "Is Mad Cow an STD?". Slate. Retrieved 2017-01-07.

- ↑ Sattar, Hussain A. Fundamentals of Pathology. Chicago: Pathoma LLC. p. 187.

- ↑ Rachael Rettner (2011-02-03). "Blood test may screen for human form of mad cow". MSNBC. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- ↑ Young, Geoffrey S.; Michael D. Geschwind; Nancy J. Fischbein; Jennifer L. Martindale; Roland G. Henry; Songling Liu; Ying Lu; Stephen Wong; Hong Liu; Bruce L. Miller; William P. Dillon (June–July 2005). "Diffusion-Weighted and Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery Imaging in Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease: High Sensitivity and Specificity for Diagnosis". American Journal of Neuroradiology. American Society of Neuroradiology. 26 (6): 1551–1562. PMID 15956529. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ Tschampa, Henriette J.; M; F; P; S; U (1 May 2003). "Thalamic Involvement in Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease: A Diffusion-Weighted MR Imaging Study". American Journal of Neuroradiology. American Society of Neuroradiology. 24 (5): 908–915. PMID 12748093. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ Sanchez-Juan P, Green A, Ladogana A, Cuadrado-Corrales N, et al. (2006). "CSF tests in the differential diagnosis of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease". Neurology. 67 (4): 637–643. PMID 16924018. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000230159.67128.00.

- ↑ Tattum, M. H.; Jones, S.; Pal, S.; Khalili-Shirazi, A.; Collinge, J.; Jackson, G. (December 2010). "A highly sensitive immunoassay for the detection of prion-infected material in whole human blood without the use of proteinase K". Transfusion. AABB. 50 (12): 2619–2627. PMID 20561299. doi:10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02731.x.

- ↑ "Detecting Prions in Blood" (PDF). Microbiology Today: 195. August 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 2011-08-21.

- ↑ Rubenstein R, Chang B, Gray P; et al. (July 2010). "A novel method for preclinical detection of PrPSc in blood". J Gen Virol. 91: 1883–92. PMID 20357038. doi:10.1099/vir.0.020164-0.

- ↑ Orrú, C.D.; Bongianni, M.; Tonoli, G.; Ferrari, S.; Hughson, A.G.; Groveman, B.R.; Fiorini, M.; Pocchiari, M.; Monaco, S.; Caughey, B.; Zanusso, G. (August 2014). "A test for Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease using nasal brushings.". New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (6): 530–9. PMC 4186748

. PMID 25099576. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1315200.

. PMID 25099576. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1315200. - 1 2 Sternberg's Diagnostic Surgical Pathology, 5th edition.

- ↑ Liberski, P. P. (2004). "Spongiform change--an electron microscopic view.". Folia Neuropathologica. 42, suppl B: 59–70.

- ↑ "CNS Degenerative Diseases".

- ↑ Belay ED, Schonberger LB (2002). "Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and bovine spongiform encephalopathy". Clin. Lab. Med. 22 (4): 849–62, v–vi. PMID 12489284. doi:10.1016/S0272-2712(02)00024-0.

- ↑ Manix, M; Kalakoti, P; Henry, M; Thakur, J; Menger, R; Guthikonda, B; Nanda, A (November 2015). "Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: updated diagnostic criteria, treatment algorithm, and the utility of brain biopsy.". Neurosurgical focus. 39 (5): E2. PMID 26646926. doi:10.3171/2015.8.FOCUS15328.

- ↑ Mizutani, T; Okumura, A; Oda, M; Shiraki, H (February 1981). "Panencephalopathic type of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: primary involvement of the cerebral white matter.". Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 44 (2): 103–15. PMID 7012278.

- ↑ http://www.upi.com/Mad-Cow-Linked-to-thousands-of-CJD-cases/47861072816318/

- 1 2 "CJD (Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease, Classic)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008-02-26. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- 1 2 "vCJD (Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007-01-04. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- 1 2 Collinge J, Whitfield J, McKintosh E (June 2006). "Kuru in the 21st century—an acquired human prion disease with very long incubation periods". Lancet. 367 (9528): 2068–74. PMID 16798390. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68930-7.

- 1 2 Diamond, JM (7 September 2000). "Archaeology: Talk of cannibalism". Nature. 407 (25–26): 25–6. PMID 10993054. doi:10.1038/35024175.

- ↑ Berger JR, Waisman E, Weisman B (August 1997). "Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and eating squirrel brains". Lancet. 350 (9078): 642. PMID 9288058. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63333-8.

- ↑ "Warning over second wave of CJD cases". The Observer. 8 August 2008. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ↑ Diack, Abigail B; Head, Mark W; McCutcheon, Sandra; Boyle, Aileen; Knight, Richard; Ironside, James W; Manson, Jean C; Will, Robert G (1 November 2014). "Variant CJD". Prion. 8 (4): 286–295. ISSN 1933-6896. PMC 4601215

. PMID 25495404. doi:10.4161/pri.29237.

. PMID 25495404. doi:10.4161/pri.29237. - ↑ Ironside, J. W. (1996). "Neuropathological diagnosis of human prion disease; morphological studies". In H. F. Baker; R. M. Ridley. Prion Diseases. pp. 35–57. ISBN 978-0-89603-342-9.

- ↑ Meggendorfer F (1930). "Klinische und genealogische Beobachtungen bei einem Fall von spastischer Pseudokosklerose Jakobs". Zeitschrift für die gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatrie. 128: 337–41. doi:10.1007/bf02864269.

- ↑ Gambetti P, Kong Q, Zou W, Parchi P, Chen SG (2003). "Sporadic and familial CJD: classification and characterisation". British Medical Bulletin. 66: 213–39. PMID 14522861. doi:10.1093/bmb/66.1.213.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Emerging Infectious Diseases: "Is Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease Transmitted in Blood?" (Ricketts et al.) vol 3, Jun 1997

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1997: Stanley B. Prusiner". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ↑ Manuelidis L, Yu ZX, Barquero N, Banquero N, Mullins B (February 2007). "Cells infected with scrapie and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease agents produce intracellular 25-nm virus-like particles". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (6): 1965–70. PMC 1794316

. PMID 17267596. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610999104.

. PMID 17267596. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610999104. - ↑ Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease (CJD)—the facts—Infectious Diseases Epidemiology & Surveillance—Department of Health, Victoria, Australia

- ↑ Mad cow link in hunter's death | Stuff.co.nz

- ↑ "Estimate doubled for vCJD carriers in UK". BBC News. 2013-10-15.

- ↑ Gill, Noel (2013). "Prevalent abnormal prion protein in human appendixes after bovine spongiform encephalopathy epizootic: large scale survey". British Medical Journal. 347: f5675. PMC 3805509

. PMID 24129059. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5675. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

. PMID 24129059. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5675. Retrieved 27 December 2013. - ↑ "Autopsy confirms rare brain disease in NH patient". MyFoxBoston. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ "NH PATIENT LIKELY DIED OF RARE BRAIN DISEASE". AP. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ↑ Kowalczyk, Liz. "5 patients at Cape hospital at risk for rare brain disease". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ↑ http://www.heraldextra.com/news/local/central/provo/officials-lockhart-died-from-creutzfeldt-jakob-disease/article_ab2ba7d7-26b0-5e7a-8347-3142e5ded8cc.html

- ↑ Schudel, Matt (June 14, 2015). "John S. Carroll, acclaimed newspaper editor in Baltimore and L.A., dies at 73". The Washington Post.

- ↑ http://variety.com/2016/tv/news/barbara-tarbuck-dead-dies-general-hospital-jane-jacks-ahs-1201950002/

- ↑ "Teenager with vCJD 'stable". London: BBC News. 13 December 2004. Retrieved 2007-01-01.

- ↑ Bone, Ian (12 July 2006). "Intraventricular Pentosan Polysulphate in Human Prion Diseases: A study of Experience in the United Kingdom". Medical Research Council. Retrieved 2012-11-09.

- ↑ "Belfast man with vCJD dies after long battle". London: BBC News. 7 March 2011. Retrieved 2013-04-11.

- ↑ "Use of Pentosan Polysulphate in the treatment of, or prevention of, vCJD". Department of Health:CJD Therapy Advisory Group. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ Rainov NG, Tsuboi Y, Krolak-Salmon P, Vighetto A, Doh-Ura K (2007). "Experimental treatments for human transmissible spongiform encephalopathies: is there a role for pentosan polysulfate?". Expert opinion on biological therapy. 7 (5): 713–26. PMID 17477808. doi:10.1517/14712598.7.5.713.

- ↑ Pfeifer A, Eigenbrod S, Al-Khadra S (December 2006). "Lentivector-mediated RNAi efficiently suppresses prion protein and prolongs survival of scrapie-infected mice". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 116 (12): 3204–10. PMC 1679709

. PMID 17143329. doi:10.1172/JCI29236. Lay summary – BBC News (2006-12-04).

. PMID 17143329. doi:10.1172/JCI29236. Lay summary – BBC News (2006-12-04). - ↑ Collinge, J; Gorham, M; Hudson, F; Kennedy, A; Keogh, G; Pal, S; Rossor, M; Rudge, P; Siddique, D; Spyer, M; Thomas, D; Walker, S; Webb, T; Wroe, S; Darbyshire, J (April 2009). "Safety and efficacy of quinacrine in human prion disease (PRION-1 study): a patient-preference trial". Lancet neurology. 8 (4): 334–44. PMC 2660392

. PMID 19278902. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70049-3.

. PMID 19278902. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70049-3. - ↑ Karapetyan, Yervand Eduard; Gian Franco Sferrazza; Minghai Zhou; Gregory Ottenberg; Timothy Spicer; Peter Chase; Mohammad Fallahi; Peter Hodder; Charles Weissmann; Corinne Ida Lasmézas (2013). "Unique drug screening approach for prion diseases identifies tacrolimus and astemizole as antiprion agents". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (17): 7044–7049. PMC 3637718

. PMID 23576755. doi:10.1073/pnas.1303510110. Lay summary – Scripps Research Institute News Release (April 3, 2013).

. PMID 23576755. doi:10.1073/pnas.1303510110. Lay summary – Scripps Research Institute News Release (April 3, 2013).

External links

| Classification |

V · T · D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease at DMOZ

- UCSF Memory and Aging Center—education website from a CJD patient care and research center

- CJD animation