Glossary of plant morphology

This page provides a glossary of plant morphology. Botanists and other biologists who study plant morphology use a number of different terms to describe plant organs and parts that can be observed with the human eye using no more than a hand-held magnifying lens. These terms are used to identify and classify plants. This page is provided to help in understanding the numerous other pages describing plants by their various taxa. The accompanying page Plant morphology provides an overview of the science of studying the external form of plants. There is also an alphabetical list, a Glossary of botanical terms, while this page deals with botanical terms in a systematic manner, with some illustrations. The internal structure is dealt with in Plant anatomy, and function in Plant physiology.[1]

Primarily, these are terms that deal with the vascular plants (ferns, gymnosperms and angiosperms), particularly the flowering plants (angiosperms). In contrast the non-vascular plants (bryophytes), with their different evolutionary background, tend to have their own particular terminology. Although plant morphology (the external form) is integrated with plant anatomy (the internal form), the former which requires few tools was the basis of the taxonomic description of plants that exists today.[2][3]

Since the terms used have been handed down from the earliest herbalists and botanists, as far back as Theophrastus, they are usually Greek or Latin in form. These terms have been modified and added to over the years and different authorities may not always use them in exactly the same way.[2][3] This page has two parts: The first deals with general plant terms, and the second with specific plant structures or parts.

General plant terms

- Abaxial – located on the side facing away from the axis.

- Adaxial – located on the side facing towards the axis.

- Dehiscent – opening at maturity

- Gall – outgrowth on the surface caused by invasion by other lifeforms, such as parasites

- Indehiscent – not opening at maturity

- Reticulate – web-like or network-like

- Striated – marked by a series of lines, grooves, or ridges

- Tesselate – marked by a pattern of polygons, usually rectangles

- Wing (plant) – any flat surfaced structure emerging from the side or summit of an organ; seeds, stems.

Plant habit

Plant habit refers to the overall shape of a plant. It has a number of components such as stem length and development, branching pattern, and texture. While many plants fit easily into some main categories, such as grasses, vines, shrubs or trees, others can be more difficult to categorise. The habit of a plant provides important information about its ecology, that is how it has adapted to its environment. Each habit indicates a different adaptive ecological strategy. Habit is also associated with the development of the plant and may change as the plant grows, more properly called its growth habit. In addition to shape, habit indicates its structure, for instance whether herbaceous or woody. Each plant commences its growth as a herbaceous plant, while woody plants (such as trees, shrubs and woody vines (lianas) will gradually acquire woody (lignaceous) tissues which provide strength and protection for the vascular system.[4] While woody plants tend to be tall and relatively long lived, herbaceous plants are shorter and seasonal, dying back at the end of their growth season. The formation of woody tissue is an example of secondary growth, a change in existing tissues, in contrast to primary growth that creates new tissues, such as the elongating tip of a plant shoot. The process of wood formation (lignification) is commonest in the Spermatophytes (seed bearing plants) and has evolved independently a number of times. The roots may also lignify, aiding in the role of supporting and anchoring tall plants, and may be part of a descriptor of the plant's habit.

Another plant habit refers to whether the plant possesses any specialised systems for the storage of carbohydrates or water, allowing it to renew growth after an unfavourable period. Where the amount of water stored is relatively high, the plant is referred to as a succulent. Such specialised plant parts may arise from the stems or roots. Examples include plants growing in unfavourable climates, very dry climates where storage is intermittent depending on climatic conditions, and those adapted to surviving fires that can regrow from the soil afterwards.

Some types of plant habit include:

- Herbaceous plants (also called Herbs): A plant in which all structures above the surface of the soil, vegetative or reproductive, die back at the end of the annual growing season, and never become woody. While these structures are annual in nature, the plant itself may be annual, biannual, or perennial. Herbaceous plants that survive for more than one season possess underground storage organs, and thus are referred to as geophytes.

Terms used in describing plant habit, include:

- Acaulescent – the leaves and inflorescence rise from the ground, appearing to have no stem. Some such growth forms are also known as rosette form. One of the many conditions that results from very short [internode (botany)|internodes]] (i.e. close distances between nodes on the plant stem. See also radical, where leaves arise apparently without stems.

- Acid plant – plants with acid saps, normally due to the production of ammonium salts (malic and oxalic acid)

- Acme – the period when the plant or population is at its maximum vigor.

- Actinomorphic – parts of plants that are radially symmetrical in arrangement.

- Arborescent – growing into a tree-like habit, normally with a single woody stem.

- Ascending – growing uprightly, in an upward direction, heading in the direction of the top.

- Assurgent – growth ascending.

- Branching – dividing into multiple smaller segments.

- Caducous – falling away early.

- Caulescent – with a well-developed stem above ground.

- Cespitose – forming dense tufts, normally applied to small plants typically growing into mats, tufts or clumps.

- Creeping – growing along the ground and producing roots at intervals along surface.

- Deciduous – falling away after its function is completed.

- Decumbent – growth starts off prostrate and the ends become upright.

- Deflexed – bending downward.

- Determinate growth – Growing for a limited time, floral formation and leaves (see also Indeterminate).

- Dimorphic – of two different forms.

- Ecad – a plant assumed to be adapted to a specific habitat.

- Ecotone – the boundary that separates two plant communities, generally of major rank – trees in woods and grasses in savanna for example.

- Ectogenesis – variation in plants due to conditions outside of the plants.

- Ectoparasite – a parasitic plant that has most of its mass outside of the host, the body and reproductive organs of the plant lives outside of the host.

- Epigeal – living on the surface of the ground. See also terms for seeds.

- Epilithic – growing on the surface of rocks.

- Epiphloedal – growing on the bark of trees.

- Epiphloedic – an organism that grows on the bark of trees.

- Epiphyllous – growing on the leaves. For example, Helwingia japonica has epiphyllous flowers (ones that form on the leaves).[5]

- Epiphyte – growing on another organism but not parasitic. Not growing on the ground.

- Epiphytic – having the nature of an epiphyte.

- Equinoctial – a plants that has flowers that open and close at definite times during the day.

- Erect – having an essentially upright vertical habit or position.

- Escape – plant originally under cultivation that has become wild, garden plant growing in natural areas.

- Evergreen – remaining green in the winter or during the normal dormancy period for other plants.

- Eupotamous – living in rivers and streams.

- Euryhaline – normally living in salt water but tolerant of variable salinity rates.

- Eurythermous – tolerant of a wide range of temperature.

- Exclusive species – confined to specific location.

- Exotic – not native to the area or region.

- Exsiccatus – a dried plant, most often used for specimens in a herbarium.

- Indeterminate growth – Inflorescence and leaves growing for an indeterminate time, until stopped by other factors such as frost (see also Determinate).

- Lax – non upright, growth not strictly upright or hangs down from the point of origin.

- Parasitic – using another plant as a source of nourishment.

- Precocious – flowering before the leaves emerge.

- Procumbent – growing prostrate or trailing but not rooting at the nodes.

- Prostrate – lying flat on the ground, stems or even flowers in some species.

- Repent – creeping.

- Rosette – cluster of leaves with very short internodes that are crowded together, normally on the soil surface but sometimes higher on the stem.

- Rostellate – like a rosette (cf. rostellum).

- Rosulate – arranged into a rosette.

- Runner – an elongated, slender branch that roots at the nodes or tip.

- Stolon – A branch that forms near the base of the plant and grows horizontally and roots and produces new plants at the nodes or apex.

- Stoloniferous – plants produce stolons.

- Semi-erect – Not growing perfectly straight.

- Suffrutescent – somewhat shrubby, or shrubby at the base.

- Upright – Growing upward.

- Virgate – wand-like, slender erect growing stem with many leaves or very short branches.

- Woody – forming secondary growth laterally around the plant so as to form wood.

Duration

Duration of individual plant lives are described using these terms:

- Annual – plants that live, reproduce and die in one growing season.

- Biennial – plants that need two growing seasons to complete their life cycle, normally vegetative growth the first year and flowering the second year.

- Herbs – see herbaceous.

- Herbaceous – plants with shoot systems that die back to ground each year – both annual and non-woody perennial plants.

- Herbaceous perennial – non-woody plants that live for more than two years and the shoot system dies back to the soil level each year.

- Woody perennial – true shrubs and trees or some vines with shoot systems that remain alive above the soil surface from one year to the next.

- Monocarpic – plants that live for a number of years then after flowering and seed set die.

Plant structures

Introduction

Plant structures or organs fulfil specific functions, and those functions determine the structures that perform them. Among terrestrial (land) plants, the vascular and non-vascular plants (Bryophytes) evolved independently in terms of their adaptation to terrestrial life and are treated separately here (see Bryophytes).[6]

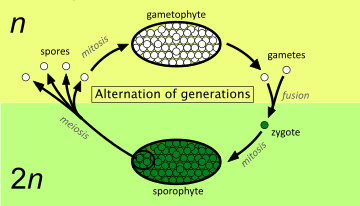

Life cycle

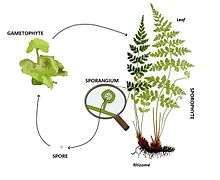

Their common elements occur in the embryonic part of the life cycle, which is their diploid multicellular phase. The embryo develops into the sporophyte, which at maturity produces haploid spores, which germinate to produce the gametophyte, the haploid multicellular phase. The haploid gametophyte then produces gametes, which may fuse to form a diploid zygote and finally an embryo. This phenomenon of alternating diploid and haploid multicellular phases is common to the embryophytes (land plants) and is referred to as the alternation of generations. A major difference between non vascular and vascular plants is that in the former the haploid gametophyte is the more visible and longer lived stage. In the vascular plants, the diploid sporophyte has evolved as the dominant and visible phase of the life cycle. In seed plants and some other groups of vascular plants the gametophyte phases are strongly reduced in size and contained within the pollen and ovules. The female gametophyte is entirely contained within the sporophyte's tissues, while the male gametophyte in its pollen grain is released and transferred by wind or animal vectors to fertilize the ovules.[1]

Morphology

Amongst the vascular plants the structures and functions of the Pteridophyta (ferns) which reproduce seedlessly are also sufficiently different to justify separate treatment, as here (see Pteridophytes). The remainder of the vascular plant sections address the higher plants (Spermatophytes or Seed Plants, i.e. Gymnosperms and Angiosperms or flowering plants). In the higher plants the terrestrial sporophyte has evolved specialised parts. In essence they have an underground component and an upper aerial component. The lower underground part develops roots that seek water and nourishment from the soil, while the upper component or shoot moves towards the light and develops a plant stem, leaves and specialised reproductive structures (sporangia). In angiosperms, the sporangia are located in the stamen anthers (microsporangia) and ovules (megasporangia). The specialised sporangia bearing stem is the flower. In angiosperms, if the female sporangium is fertilised, it becomes the fruit, a mechanism for dispersing the seeds produced from the embryo. [6]

Vegetative structures

Thus the terrestrial sporophyte has two growth centres, the stem growing upwards while the roots grow downwards. New growth occurs at the tips (apices) of the shoot and roots where the undifferentiated cells of the meristem divide. Branching occurs to form new apical meristems. Growth of the stem is indeterminate in pattern (not pre-determined to stop at a particular point).[1] The functions of the stem are to raise and support the leaves and reproductive organs above the level of the soil to facilitate absorption of light for photosynthesis, gas exchange, water exchange (transpiration) pollination and seed dispersal. It also serves as a conduit for water and other growth substances between the roots and overhead structures. This occurs in specialised tissues known as vascular bundles, which give the name 'vascular plants' to the angiosperms. The point of insertion on the stem of leaves or buds is a node, and the space between two successive node, an internode.

Also emerging from the shoot are the leaves, specialised structures that carry out photosynthesis, and gas (oxygen and carbon dioxide) and water exchange. They are lined by an outer layer or epidermis, coated with a waxy waterproof protective layer, but punctuated by specialised pores, known as stomata, which regulate gas and water exchange. The leaves also possess vascular bundles, which are generally visible as veins, and their pattern is called venation. Leaves tend to have a shorter life span than the stems or branches that bear them, and when they fall, an area at the attachment zone, called an abscission zone leaves a scar on the stem.

In the angle (adaxial) between the leaf and the stem, is the axil. Here can be found buds (axillary buds), which are miniature and often dormant branches with their own apical meristem. They are often covered by leaves.

Floral structure

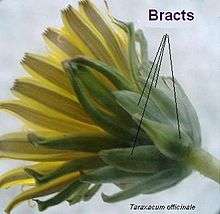

The flower, which is one of the defining features of angiosperms, is essentially a stem, whose leaf primordia become specialised, following which the apical meristem stops growing, a determinate growth pattern, in contrast to vegetative stems.[1][6] The flower stem is known as a pedicel, and those flowers with a stalk are called pedicellate, while those without are called sessile.[7] In the angiosperms, the flowers are arranged on a flower stem as an inflorescence, though these structures are very different in gymnosperms and angiosperms, which are dealt with in more detail here. Just beneath (subtended) the flower there may be a modified and usually reduced leaf, called a bract. A secondary smaller bract is a bracteole (bractlet, prophyll, prophyllum), often on the side of the pedicel, and generally paired. A series of bracts subtending the calyx (see below) is an epicalyx.[7]

In angiosperms, the specialised leaves that play a part in reproduction are arranged around the stem in an ordered fashion, from the base to the apex of the flower. The floral parts are arranged at the end of a stem without any internodes, the receptacle (also called the floral axis, or thalamus) which is generally very small. Some flower parts are solitary, while others may form a tight spiral or whorl, around the flower stem. First, at the base, are those non-reproductive structures involved in protecting the flower when it is still a bud, the sepals, then those parts that play a role in attracting pollinators and are typically coloured, the petals, which together with the sepals make up the perianth (perigon, perigonium). If the perianth is not differentiated into sepals and petals, they are collectively known as tepals. If the perianth is differentiated, the outer whorl of sepals forms the calyx, and the inner whorl of petals, the corolla. In some flowers, a tube or cup like hypanthium (floral tube) is formed above or around the ovary and bears the sepals, petals and stamens. There may also be a nectary producing nectar. Nectaries may develop on or in the perianth, receptacle, androecium (stamens), or gynoecium. In some flowers nectar may be produced on nectariferous disks. Disks may arise from the receptable and are doughnut or disk shaped. They may also surround the stamens (extrastaminal), be at their bases (staminal) or be inside the stamina (intrastaminal).[8]

Reproductive structures

Finally, the actual reproductive parts form the innermost layers of the flower. These leaf primordia become specialised as sporophylls, leaves that form areas called sporangia, which produce spores, and cavitate internally. The sporangia on the sporophytes of pteridophytes are visible, but those of gymnosperms and angiosperms are not. In the angiosperms there are two types. Some form male organs (stamens), the male (microsporangia), producing microspores. Others form female organs (carpels), the female (megasporangia) which produce a single large megaspore.[8] These in turn produce the male gametophytes and female gametophytes

These two components are the androecium and gynoecium respectively. The Androecium (literally, men's house) is a collective term for the male organs (stamens or microsporophylls). While sometimes leaflike (laminar), more commonly they consist of a long thread-like column, the filament, surmounted by a pollen bearing anther. The anther usually consists of two fused thecae. A theca is two microspoorangia. The gynoecium (women's house) is the collective term for the female organs (carpels). A carpel is a modified megasporophyll consisting of two or more ovules, which develops conduplicatively (folded along the line). The carpels may be single of collected together to form an ovary, and contain the ovules. Another term, pistil, refers to the ovary as its expanded base, the style, a column arising from the ovary, and an expanded tip, the stigma.[8]

Within the stamen the microsporangium forms grains of pollen, surrounded by the protective microspore, which forms the male gametophyte. Within the carpel the megasporangium form the ovules, with its protective layers (integument) in the megaspore, and the female gametophyte. Unlike the male gametophyte, which is transported in the pollen, the female gametophyte remains within the ovule.[8]

Most flowers have both male and female organs, and hence are considered bisexual (perfect), which is thought to be the ancestral state. However others have either one or the other and are therefore unisexual or imperfect. In which case they may be either male (staminate) or female (pistillate). Plants may bear either all bisexual flowers (hermaphroditic), both male and female flowers (monoecious) or only one sex (dioecious), in which case separate plants are either male or female flower bearing. Where both bisexual and unisexual flowers exist on the same plant, it is called polygamous. Polygamous plants may have bisexual and staminate flowers (andromonoecious) or bisexual and pistillate flowers (gynomonoecious), or both (trimonoecious). Other combinations include the presence of bisexual flowers on some individual plants and staminate on others (androdioecious) or bisexual and pistillate (gynodioecious). Finally trioecious plants have bisexual, staminate or pistillate flowers on different individuals. Arrangements other than hermaphroditic help to ensure outcrossing.[9]

Fertilisation and embryogenesis

The development of the embryo and gametophytes is called embryology. The study of pollens which persist in soil for many years is called palynology. Reproduction occurs when male and female gametophytes interact. This generally requires an external agent such as wind or insects to carry the pollen from the stamen to the vicinity of the ovule. This process is called pollination. In gymnosperms (literally naked seed) pollen comes into direct contact with the exposed ovule. In angiosperms the ovule is enclosed in the carpel, requiring a specialised structure, the stigma, to receive the pollen. On the surface of the stigma, the pollen germinates, that is the male gametophyte penetrates the pollen wall into the stigma, and a pollen tube, an extension of the pollen grain extends towards the carpel carrying with it the sperm cells (male gametes) till they encounter the ovule, where they gain access through a pore in the integument (micropyle) allowing fertilisation to occur. Once the ovule has been fertilised, a new sporophyte develops, protected and nurtured by the female gametophyte, and becomes an embryo. When development stops, the embryo becomes dormant as a seed. Within the embryo are the primordial shoot and root.

In angiosperms, as the seed develops after fertilisation, so does the surrounding carpel, it walls thickening or hardening, developing colours or nutrients that attract animals or birds, often with many layers. This new entity with its dormant seeds is the fruit, whose functions are protecting the seed and dispersing it. In some cases androecium and gynaecium may be fused. The resulting structure is a gynandrium (gynostegium, gynostemium or column) and is supported by an androgynosphore.[8]

Vegetative morphology

- Ptyxis – the way in which an individual leaf is folded within an unopened bud.

- Vernation – the arrangement of leaves in an unopened bud.

Roots

Roots generally do not offer many characters used in plant identification and classification, but are important in determining plant duration. In some groups, however, including the grasses, they are very important for proper identification .

- Adventitious – roots that form from other than the hypocotyl or from other roots. Roots forming on the stem are adventitious.

- Aerial – roots growing in the air.

- (Root) crown – the place where the roots and stem meet, which may or may not be clearly visible.[10]

- Fibrous – describes roots that are thread-like and normally tough.

- Fleshy – describes roots that are relatively thick and soft, normally made up of storage tissue. Roots are typically long and thick but not thickly rounded in shape.

- Haustorial – specialized roots that invade other plants and absorb nutrients from those plants.

- Lignotuber – root tissue that allows plants to regenerate after fire or other damage.

- Primary – roots that develops from the radicle of the embryo, normally the first root to emerge from the seed as it germinates.

- Root Hairs – very small roots, often one cell wide, that do most of the water and nutrient absorption.

- Secondary – roots forming off of the primary root, often called branch roots.

- Taproot – a primary root that more or less enlarges and grows downward into the soil.

- Tuberous – describes roots that are thick and soft, with storage tissue. Typically thick round in shape.

Terms on Root structure:

- Epiblema- Outermost (epidermal) layer of rootlets. Normally 1-cell-layer thick (uniseriate). Normally do not have a cuticle, and permit water conduction.

- Quiescent centre - a small region inside root apical region with slower division rate.

- Root Cap - a cover or cap like structure that protects the tip of root.

- Multiple root-caps - several layer of root-caps on the single root-apex. Seen in Pandanus sp.

- Root Pocket - a cap-like structure on the root-apex of some aquatic plants, which, unlike root-caps, doesn't reappear if removed somehow.

- Root hair - fine cellular appendages from cells of epiblema. They are unicellular* that means one root hair (and corresponding cell of epiblema) is made up of only 1 cell (*not to be confused with unicellular organisms). In contrast, stem and leaf hairs could be unicellular or multicellular. Root hairs of older portion of root get destroyed with time, and only at certain region near growing apex (called root-hair-region) the root hairs could be seen. Although microscopic, root-hairs could be observed in unaided eye in chilli and Brassica seedlings.

Terms on Classification of Roots and its modifications

- Tap-Root-System:

- Storage roots:

- Conical root - Storage root which is broad at root's base (upper portion) and gradually tapering at the apex (downward portion). eg. Carrot.

- Fusiform Root - Storage root swollen at centre and tapers towards both apex and base. eg. radish (Raphanus sativus)

- Napiform root - Root heavily swollen at upper (root's basal) portion but narrow and tapering at lower (root's apical) portion. eg. Beet, turnip.

- Tuberous or Tubercular tap-root - (narrow sense)- tap-root thick and fleshy (due to storage) but do not conform with the fusiform/ conical/ napiform shape. eg. Mirabilis jalapa. (Broader sense)- tap-root thick and fleshy (due to storage). i.e. when tuberation take place in tap-root.

- Pneumatophores (respiratory roots) - Part of tap-root-system as respiratory roots, found in many mangrove-trees. They arise from the thick, mature branches of tap-root systems, and grow upwards. The inner tissue of respiratory root is full of hollow, airy, tube-like dead cells, giving it a spongy context. The outer surface of pneumatophore contain tiny pores or openings, which are called pneumathodes. eg. Heritiera fomes, Rhizophora mucronata, etc. Pneumatophores could be unbranched or sparingly branched.

- Vivipary - This is also feature of many mangrove trees, where the seed germinates when the seed (and fruit) remain joined with mother plant until The radicle and hypocotyl grows, reaches the ground and establish there [11]

- Storage roots:

. (See also: seeds and germination related sections and articles)

- Adventitious root systems

- Fibrous root - They originate from the base of young stem replacing the primary root, (and also from the stem nodes, and sometimes internodes) and released as a parallel cluster or bunch from around the node. The adventitious roots of monocots are usually this type. Replacement of tap root system by fibrous root, is seen in Onion, tuberose (Polyanthes tuberosa), grasses, etc. Fibrous roots from normal-stem's nodes seen in grasses like maize, sugarcane, bamboo, etc. Fibrous roots from nodes also helps in survival of the plant and thus in vegetative reproduction, when the plant's base damaged or a damage or cut take place inside stem axis.

- Seminal root -

- Many dicots too, release adventitious toots from stem-nodes, especially those can regenerate vegetitively (Hibiscus rosa-sinensis, Coleus sp etc) and those have a week stem with creeping habit (Centella asiatica, Bacopa monnieri) etc. and these roots are not called as fibrous root, rather called only as adventitious roots.

- Adventitious storage roots - (similar function as storage-taproots)

- Tuberous roots or root tubers- (narrow sense)- Those storage roots do-not conform a specific shape such as fasciculated, nodulose moniliform, annulated etc. eg. Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) edible part is this-type of root. (Broader sense)- adventitious roots swollen due to storage function.

- Fasciculated root - When several tubercular roots grow as a parallel bunch or bundle. Seen in Dahlia sp., Ruellia tuberosa, Asparagus racemosus, etc. Orchis maculata have a pair of bulbous storage-roots.

- Nodulose root - (Not to be confused with root-nodules, a completely different thing), in nodulose root, the storage pattern is, a root axis swollen near the apical portion, thus forming a bulbous or tuberous structure on or near the tip of root. It is commonly seen associated with rhizomatous stem. It is seen in Costus speciosus[12],Curcuma amada[13][14] , Curcuma domestica, Asparagus sprengeri, Arrowroot (Maranta), etc.[15] and some (?) species of Calathea[16].

- Moniliform root or Beaded root - When more-than-one swelling (nodule-like structures) occur at certain intervals along the root-axis. Such alternating swollen and constricted pattern is seen in Cyperus sp. , Dioscorea alata[17], Vitis trifolia, Portulaca sp. , Basella sp., Momordica sp. and some(?) grasses[18].

- Annulated root - Just like moniliform roots, annulated roots also contain alternating swollen and constricted regions. But here the length of constricted regions are so short that the root appears as a stack of discs. It is seen in Cephalis ipecacuanha (Rubiaceae).

- Floating root or Aquatic-respiratory root- seen in Jussiaea repens. the upright, spongy structures helps the plant to float[19][20].

- Epiphytic root - This type of root seen in epiphytic orchids. The thick root hangs from the plant's base directly into air. The root is covered with a special, usually 4- to 5 cell layer thick[21], spongy tissue (called Velamen) , which helps the plant to absorb the moisture from atmosphere. (Epiphytic orchid have another sort of root, called clinging roots, that help the orchid plant cling the substratum (host). Since the similar function is seen in many other plant's adventitious roots, it is being mentioned in more general way at the mechanical advancements section.)

- Parasitic root or Haustoria -

- Assimilatory or Photosynthetic roots -

- Mechanical advancements :

- Prop-roots - In some dome-shaped (deliquescent) trees, from the mature horizontal boughs (stem-branches) some quite thick (milimeters to centimeters) roots come down. After grow and reach the ground, they establish more elaborate root branches as well show massive secondary thickening. Thus they start to resemble the main trunk. These roots are called prop-roots. Besides carrying the weight of horizontal boughs, when the main trunk get destroyed due to ageing or accident, the established prop-roots support the remaining plant-body, thus help in vegetative reproduction. eg. Ficus benghalensis. The Great Banyan Tree at IBG Kolkata is an example how prop-root help in vegetative reproduction.

- Stilt roots - From upright (erect) trunks, some hard, thick, almost straight roots come-out obliquely and penetrate the ground. Thus they act like a camera-tripod. They increase balance and support as well as when these roots penetrates the ground, they increase grip with soil.

- Root-Buttress or Plank Buttress or Buttress-Root -

- Climbing roots -

- Clinging roots -

- Contractile-roots or Pull-roots -

- Haptera -

- Fibrous root - They originate from the base of young stem replacing the primary root, (and also from the stem nodes, and sometimes internodes) and released as a parallel cluster or bunch from around the node. The adventitious roots of monocots are usually this type. Replacement of tap root system by fibrous root, is seen in Onion, tuberose (Polyanthes tuberosa), grasses, etc. Fibrous roots from normal-stem's nodes seen in grasses like maize, sugarcane, bamboo, etc. Fibrous roots from nodes also helps in survival of the plant and thus in vegetative reproduction, when the plant's base damaged or a damage or cut take place inside stem axis.

| Gallery: Roots specialized for mechanical function. | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

- Protective functions -

- Root-thorns -

- Reproductive roots - These roots contain root-buds and actively take part in shoot-regeneration, and thus in vegetative reproduction. This is a sort of unusual feature because roots normally do not contain buds.

- Protective functions -

Stems

- Accessory buds – an embryonic shoot occurring above or to the side of an axillary bud;also known as supernumerary bud.

- Acrocarpous – produced at the end of a branch.

- Acutangular – a stem that has several longitudinally running ridges with sharp edges.

- Adventitious buds – a bud that arises at points on the plant other than at the stem apex or a leaf axil.

- Alate – Having wing-like structures, usually on the seeds or stems, as in Euonymus alata

- Alternate – buds are staggered on opposite sides of the branch

- Bark – the outer layers of woody plants; cork, phloem, and vascular cambium.

- Branches –

- Bud – an immature stem tip, typically an embryonic shoot, ether producing a stem, leaves or flowers.

- Bulb – an underground stem normally with a short basal surface and with thick fleshy leaves.

- Bundle scar — A small mark on a leaf scar indicating a point where a vein from the leaf was once connected with the stem.

- Caudex – the hard base produced by herbaceous perennials used to overwinter the plant.

- Caulescent – with a distinctive stem.

- Cauliflora – with the flowers and fruit on the stem or trunk as in Saraca cauliflora

- Cladode — A flattened stem that performs the function of a leaf; an example is the pad of the opuntia cactus.

- Cladophyll – a flattened stem that is leaf-like and green – used for photosynthesis, normally plants have no or greatly reduced leaves.

- Climbing – typically long stems, that cling to other objects.

- Corm – a compact, upright orientated stem that is bulb-like with hard or fleshy texture and normally covered with papery, thin dry leaves. Most often produced under the soil surface.

- Cuticle – a waterproof waxy membrane covering leaves and primary shoots.

- Decumbent – stems that lie on the ground but have the ends turning upward.

- Dormant – a state of no growth or reduced growth

- Earlywood —The portion of the annual ring that is formed during the early part of a tree's growing.

- Epidermis – a layer of cells that cover all primary tissue, separating them from the outside environment.

- Erect – growing upright.

- Flower bud — a bud from which only a flower or flowers develop

- Fruticose – woody stemmed with a shrub-like habit. Branching near the soil with woody based stems.

- Guard cell — One of the paired epidermal cells that control the opening and closing of a stoma in plant tissue.

- Herbaceous – non-woody and dying to the ground at the end of the growing season. Annual plants die, while perennials regrow from parts on the soil surface or below ground the next growing season.

- Heartwood —The older, nonliving central wood of a tree or woody plant, usually darker and harder than the younger sapwood. Also called duramen.

- Internode – spaces between the nodes.

- Latent buds – An axillary bud whose development is inhibited, sometimes for many years, due to the influence of apical and other buds. Also known as a dormant bud.

- Late wood – The portion of the annual ring that is formed after formation of earlywood has ceased.

- Lateral buds — A bud located on the side of the stem, usually in a leaf axil.

- Leaf – the photosynthetic organ of a plant that is attached to a stem, generally at specific intervals.

- Leaf axils – the space created between a leaf and its branch. This is especially pronounced on monocots like bromeliads.

- Leaf buds – A bud that produces a leafy shoot.

- Leaf scar – the mark left on a branch from the previous location of a bud or leaf.

- Lenticel – One of the small, corky pores or narrow lines on the surface of the stems of woody plants that allow the interchange of gases between the interior tissue and the surrounding air.

- Node – where leaves and buds are attached to the stem.

- Orthotropic growth – growth in a vertical direction.

- Chambered pith – A form of pith in which the parenchyma collapses or is torn during development, leaving the sclerenchyma plates to alternate with hollow zones

- Diaphragmed pith – Pith in which plates or nests of sclerenchyma may be interspersed with the parenchyma.

- Spine – an adapted leaf that is usually hard and sharp and is used for protection, and occasionally shading, of the plant

- Plagiotropic growth – growth inclined away from the vertical, inclined towards the horizontal

- Prickle – an extension of the cortex and epidermis that ends with a sharp point.

- Prostrate – growing flat on the soil surface.

- Rhizome – A horizontally orientated, prostrate stem with reduced scale-like leaves, normally growing under ground but also at the soil surface. Also produced by some species that grow in trees or water.

- Rootstock – the underground part of a plant normally referring to a caudex or rhizome.

- Runner – an above-ground stem, usually rooting and producing new plants at the nodes.

- Scandent – a stem that climbs.

- Pith – the spongy tissue at the center of a stem.

- Stem – vascular tissue that provides support for the plant,

- Stolon – a horizontally growing stem similar to a rhizome, produced near the base of the plant. They spread out above or along the soil surface. Roots and new plants develop at the nodes or ends.

- Stoloniferous – a plant that produces stolons.

- Suberose – Having a corky texture.

- Tendril – a thigmotropic organ which attaches a climbing plant to a support, a portion of a stem or leaf modified to serve as a holdfast to other objects.

- Terminal – at the end of a stalk or stem.

- Terminal scale bud scar –

- Thorn –

- Tiller – a shoot of a grass plant.

- Tuber – an enlarged stem or root that stores nutrients.

- Turgid – swollen.

- Twigs –

- Opposite – buds are arranged in pairs on opposite sides of the branch

- Pore –

- Rhizome – an underground stem, typically horizontal, that sends out roots and shoots.

- Sapwood –

- Stoma – a small pore on the surface of the leaves used for gas exchange with the environment while preventing water loss.

- Vascular bundles – a strand of woody fibers and associated tissues.

- Verticillate/Verticil/Verticillatus – leaves or flowers arranged in whorls, as in Sciadopitys verticillata

- Whorled – said of a collection of three or more leaves or flowers that arise from the same point.

Buds

- Accessory bud – an embryonic shoot occurring above or to the side of an axillary bud; also known as supernumerary bud.

- Adventitious bud – a bud that arises at a point on the plant other than at the stem apex or a leaf axil.

- Axillary – an embryonic shoot which lies at the junction of the stem and petiole of a plant.

- Dormant – see Latent bud

- Epicormic – vegetative buds that lie dormant beneath the bark, shooting after crown disturbance[22]

- Flower bud –

- Lateral –

- Latent bud – An axillary bud whose development is inhibited, sometimes for many years, due to the influence of apical and other buds. Also known as a dormant bud.

- Leaf bud – A bud that produces a leafy shoot.

- Mixed – buds that have both embryonic flowers and leaves.

- Naked –

- Pseudoterminal –

- Reproductive – buds with embryonic flowers.

- Scaly –

- Terminal – bud at the tip or end of the stem.

- Vegetative – buds containing embryonic leaves.

Leaves

Leaf Parts: – A complete leaf is composed of a blade, petiole and stipules and in many plants one or more might be lacking or highly modified.

- Blade – see lamina

- Lamina – the flat and laterally-expanded portion of a leaf blade

- Leaflet – a separate blade among others comprising a compound leaf

- Ligule – a projection from the top of the sheath on the adaxial side of the sheath-blade joint in grasses

- Midrib – the central vein of the leaf blade

- Midvein – the central vein of a leaflet

- Petiole – a leaf stalk supporting a blade and attaching to a stem at a node

- Petiolule - the leaf stalk of a leaflet

- Pulvinus – the swollen base of a petiole or petiolule usually involved in leaf movements and leaf orientation

- Rachilla – a secondary axis of a multiply compound leaf

- Rachis – main axis of a pinnately compound leaf

- Sheath – the proximal portion of a grass leaf usually surrounding the stem

- Stipules – paired scales, spines, glands, or blade-like structures at the base of a petiole

- Stipels – paired scales, spines, glands, or blade-like structures at the base of a petiolule

- Stipuloid – resembling stipules.

Duration of leaves:

- Deciduous – leaves are shed after the growing season

- Evergreen – leaves are retained throughout the year, sometimes for several years

- Fugacious – lasting for a short time: soon falling away from the parent plant.

- Marcescent – dead leaves, calyx or petals are persistent, retained

- Persistent – see Marcescence

- Acrodromous – when the veins run parallel to the leaf edge and fuse at the leaf tip.

- Actinodromous – when the main veins of a leaf radiate from the tip of the petiole.

- Brochidodromous – the veins turn away from the leaf edge to join the next higher vein.

- Campylodromous – with secondary veins that diverge at the base of the lamina and rejoin at the tip.

- Craspedodromous – secondary veins run straight to the leaf edge and end there.

- Furcate – forked, dividing into two divergent branches.

- Reticulate – veins interconnected to form a network. Net-veined.

- Vein – the externally visible vascular bundles, found on leaves, petals and other parts.

- Veinlet – a small vein.

Leaf Arrangement or Phyllotaxy:

- Whorl – three or more leaves or branches or pedicels arising from the same node.

Leaf Type:

- Abruptly pinnate – a compound leaf without a terminal leaflet.

Leaf Blade Shape:

- Acicular (acicularis): Slender and pointed, needle-like

- Acuminate (acuminata): Tapering to a long point

- Aristate (aristata): Ending in a stiff, bristle-like point

- Bipinnate (bipinnata): Each leaflet also pinnate

- Cordate (cordata): Heart-shaped, stem attaches to cleft

- Cuneate (cuneata): Triangular, stem attaches to point

- Deltoid (deltoidea): Triangular, stem attaches to side

- Digitate (digitata): Divided into finger-like lobes

- Elliptic (elliptica): Oval, with a short or no point

- Falcate (falcata): sickle-shaped

- Flabellate (flabellata): Semi-circular, or fan-like

- Hastate (hastata): shaped like a spear point, with flaring pointed lobes at the base

- Lance-shaped, lanceolate (lanceolata): Long, wider in the middle

- Linear (linearis): Long and very narrow

- Lobed (lobata): With several points

- Obcordate (obcordata): Heart-shaped, stem attaches to tapering point

- Oblanceolate (oblanceolata): Top wider than bottom

- Oblong (oblongus): Having an elongated form with slightly parallel sides

- Obovate (obovata): Teardrop-shaped, stem attaches to tapering point

- Obtuse (obtusus): With a blunt tip

- Orbicular (orbicularis): Circular

- Ovate (ovata): Oval, egg-shaped, with a tapering point

- Palmate (palmata): Divided into many lobes

- Pedate (pedata): Palmate, with cleft lobes

- Peltate (peltata): Rounded, stem underneath

- Perfoliate (perfoliata): Stem through the leaves

- Pinnate (pinnata): Two rows of leaflets

- odd-pinnate : pinnate with a terminal leaflet

- paripinnate, even-pinnate : pinnate lacking a terminal leaflet

- Pinnatisect (pinnatifida): Cut, but not to the midrib (it would be pinnate then)

- Reniform (reniformis): Kidney-shaped

- Rhomboid (rhomboidalis): Diamond-shaped

- Round (rotundifolia): Circular

- Sagittate (sagittata): Arrowhead-shaped

- Spatulate, spathulate (spathulata): Spoon-shaped

- Spear-shaped (hastata): Pointed, with barbs

- Subulate (subulata): Awl-shaped with a tapering point

- Sword-shaped (ensiformis): Long, thin, pointed

- Trifoliate, ternate (or trifoliolate) (trifoliata): Divided into three leaflets

- Tripinnate (tripinnata): Pinnately compound in which each leaflet is itself bipinnate

- Truncate (truncata): With a squared off end

- Unifoliate (unifoliata): with a single leaf

Leaf Base Shape:

- Semiamplexicaul – the leaf base wraps around the stem, but not completely.

Leaf Blade Apex:

- Acuminate – narrowing to a point, used for other structures too.

- Acute – with a sharp rather abrupt ending point.

- Acutifolius – with acute leaves.

- Attenuate – tapering gradually to a narrow end.

Leaf Blade Margins:

- Crenulate – with shallow, small rounded teeth.

Leaf Modifications:

Epidermis and periderm texture

- Acanceous – being prickly.

- Acantha – a prickle or spine.

- Acanthocarpus – fruits are spiny.

- Acanthocladous – the branches are spiny.

- Aculeate – having a covering of prickles or needle-like growth.

- Aculeolate – having spine-like processes.

- Aden – a gland.

- Adenoid – gland like.

- Adenophore – a stalk that supports a gland.

- Adenophyllous – leaves with glands.

- Arachnoid – having a cobwebby appearance with entangled hairs.

- Bloom – the waxy coating that covers some plants.

- Canescent – with gray pubescence.

- Ciliate – with a fringe of marginal hairs.

- Coriaceouse – with a tough or leathery texture.

- Fimbriate – finely cut into fringes, the edge of a frilly petal or leaf.

- Floccose –

- Glabrate –

- Glabrous – smooth without any pubescences at all.

- Glandular –

- Glandular-punctate – covered across the surface with glands.

- Hirsute – with long shaggy hairs, often stiff or bristly to the touch.

- Lanate – with woolly hairs. Thick wool like hairs.

- Verrucose – with a wart surface, with low rounded bumps.

- Villose – covered with fine long hairs that are not matted.

- Villosity – villous indument.

Floral morphology

- Accrescent – Growing larger after anthesis, normally used for the calyx.

- Anthesis – the period when the flower is fully open and functional, ends when the stigma or stamens wither.

Basic flower parts

Androecium

- Androecium – the stamens collectively.

- Basifixed – attached by the base.

- Connective – the part of the stamen joining the anther cells.

- Diadelphous – united by filaments to form two groups

- Didynamous – having four stamens in two pairs of unequal length

- Epipetalous – born on the corolla, often used in reference to stamens attached to the corolla.

- Exserted – sticking out past the corolla, the stamens protrude past the margin of the corolla lip.

- Extrose – opening towards the outside of the flower.

- Gynandrium – combined male & female structure

- Gynostegium – adnation of stamens and the style and stigma (Orchidaceae)

- Included –

- Introrse – opening on the inside of the corolla, the stamens are contained within the margins of the petals.

- Monodelphous – stamen filaments united into a tube.

- Poricidal – anthers opening by terminal pores.

- Staminode – a sterile stamen.

- Staminodial – (1) concerning a sterile stamen (2) flowers with sterile stamens.

- Synandrous – the anthers are connected (Araceae)

- Syngenesious – the anthers are united into a tube, the filaments are free (Asteraceae).

- Tetradynamous – having six stamens four of which are longer than the others

- Translator – a structure uniting the pollinia in Asclepiadaceae and Orchidaceae.

- Trinucleate – pollen containing three nuclei when shed.

- Valvular – anthers opening by valves or small flaps, e.g. Berberis.

- Versatile – anthers pivoting freely on the filament.

- Pollen –

- Stamen –

- Anther – the distal end of the stamen where pollen is produced, normally composed of two parts called anther-sacs and pollen-sacs (thecae).

- Filament – the stalk of a stamen

Gynoecium

- Gynoecium – the whorl of carpels. May comprise one (syncarpous) or more (apocarpous) pistils. Each pistil consists of an ovary, style and stigma (female reproductive organs of the flower).

- Apocarpus – the gynoecium comprises more than one pistil.

- Cell –

- Compound pistil –

- Funicle – the stalk that connects the ovule to the placenta.

- Funiculus –

- Loculus – the cavities located within a carpel, ovary or anther.

- Locule –

- multicarpellate –

- Placenta –

- Placentation –

- Axile –

- Basal –

- Free-central –

- Pariental –

- Septum –

- Simple pistil –

- Syncarpous – the gynoecium comprises one pistil.

- Unicarpellate –

- Stigma –

- Sessile - absent style

- Style – Position is relative to the body of the ovary.[23]

- Terminal or apical: arising at the apex of the ovary (commonest)

- Subapical: arising from the side of the ovary just below the apex

- Lateral: arising from the side of the ovary, lower than subapical

- Gynobasic: arising from the base of the ovary

- Ovary –

- Ovules –

- Pistil –

Other

- Acephalous – without a head, used for flower styles without a well-developed stigma.

- Bract – the leaf-like or scale-like leafy appendages that are located just below a flower, a flower stalk, or an inflorescence; they usually are reduced in size and sometimes showy or brightly colored.

- Calyx – the whorl of sepals at the base of a flower, the outer whorl of the perianth.

- Carpel – the ovule-producing reproductive organ of a flower, consisting of the stigma, style and ovary.

- Claw – a noticeably narrowed and attenuate organ base, typically a petal. Viola.

- Connate – when the same parts of a flower are fused to each other, petals in a gamopetalous flower. Petunia.

- Corolla – the whorl of petals of a flower.

- Corona – an additional structure between the petals and the stamens.

- Disk – an enlargement or outgrowth from the receptacle of the flower, located at the center of the flower of various plants. The term is also use as the central area of the head in composites where the tubular flowers are attached.

- Epicalyx – a series of bracts below the calyx

- Floral axis –

- Floral envelope – the perianth[24]

- Flower –

- Fruit – a structure contain all the seeds produced by a single flower.

- Hypanthium –

- Nectar – a fluid produce by nectaries high in sugar content, used to attract pollinators.

- Nectary – a gland that secrets nectar, most often found in flowers but also produced on other parts of plants too.

- Nectar disk – when the floral disk contains nectar secreting glands, often modified as its main function in some flowers.

- Pedicel – the stem or stalk that holds a single flower in an inflorescence.

- Peduncle – the part of a stem that bears the entire inflorescence, normally having no leaves or the leaves are reduce to bracts. When the flower is solitary, it is the stem or stalk holding the flower.

- Peduncular – referring to or having a peduncle.

- Pedunculate – having a peduncle.

- Perianth –

- Achlamydeous – without a perianth.

- Petal –

- Rachis –

- Receptacle – the end of the pedicel that joins to the flower were the different parts of the flower are joined together, also called the torus. In Asteraceae the top of the pedicel upon which the flowers are joined.

- Seed –

- Sepal –

- Antipetalous – when the stamens are the same number as the corolla segments and oppositely arranged the corolla segments. Primula.

- Antisepalouse – when the stamens are the same number as the calyx segments and oppositely arranged the calyx segments.

- Connective – the part of the stamen joining the anther cells.

- Tepal –

Inflorescences

- Capitulum – the flowers are arranged into a head composed of many separate unstalked flowers, the single flowers are called florets and are packed close together. The typical arrangement of flowers in the Asteraceae.

- Compound Umbel – is an umbel where each stalk of the main umbel produces another smaller umbel of flowers.

- Corymb – a grouping of flowers where all the flowers are at the same level, the flower stalks of different lengths forming a flat-topped flower cluster.

- Cyme – is a cluster of flowers were the end of each growing point produces a flower. New growth comes from side shoots and the oldest and first flowers to bloom are at the top.

- Single – one flower per stem or the flowers are greatly spread-apart as to appear they do not arise from the same branch.

- Spike – when flowers arising from the main stem are without individual flower stalks. The flowers attach directly to the stem.

- Solitary – same as single, with one flower per stem.

- Raceme – is a flower spike with flowers that have stalks of equal length. The stem tip continues to grow and produce more flowers with the bottom flowers open first and blooming progresses up the stem.

- Panicle – is a raceme with branches and each branch having a smaller raceme of flowers. The terminal bud of each branch continues to grow, producing more side shoots and flowers.

- Pedicel – stem holding a one flower in an inflorescences.

- Peduncle – stem holding an inflorescences, or a single flower.

- Umbel – were the flower head has all the flower stalks rising from the same point of the same length, the flower head is rounded like an umbrella or almost circular.

- Verticillaster – a whorled collection of flowers around the stem, the flowers produced in rings at intervals up the stem. As the stem tip continues to grow more whorls of flowers are produced. Typical in Lamiaceae.

- Verticil – flowers arranged in whorls at the nodes.

Insertion of floral parts

- Epigynous –flowers are present above the ovary

- Half-inferior –

- Hypogynous –flowers are present below the ovary

- Inferior –

- Insertion –

- Stamens –

- Ovary –

- Perigynous –

- Superior –

Specialized terms

- Wing – term used for the lateral petals of the flowers on species in Fabaceae and Polygalaceae.

- Valvate – meeting along the margins but not overlapping.

Union of flower parts

- Adelphous – the androecium with the stamen filaments partly or completely fused together.

Flower sexuality and presence of floral parts

- Achlamydeous – flower without a perianth.

- Apetalous – a flower without petals.

- Accrescent – said of the calyx when it is persistent and enlarges as the fruit grows and ripens, applied to other structure sometimes.

- Androgynous – used for the inflorescence of Carex when a spike has both staminate and pistillate flowers – the pistillate flowers are normally at the base of the spike.

- Bisexual –

- Complete – of a flower, having all the possible parts represented, thus sepals, petals, stamens, and pistils.[25]

- Gynodioecy – describes a plant species or population that has some plants that are female and some plants that are hermaphrodites.

- Homogamous – when the flower anthers and the stigma are ripe at the same time.

- Imperfect – of a flower or inflorescence, being unisexual and developing organs of only a single sex.[25]

- Naked – uncovered, stripped of leaves or lacking other covering such as sepals or petals.[25]

- Perfect – possessing both stamens and ovary (male and female parts)

Flower symmetry

- Actinomorphic – having a radial symmetry, as in regular flowers.

- Actinomorphy – when the flower parts are arranged with radial symmetry.

- Radial – Symmetric when bisected from any angle (circular)

- Unisexual –

- Zygomorphic – one axis of symmetry running down the middle of the flower so the right and left halves reflect each other.

- Zygomorphy – the type of symmetry that most irregular flowers have with the upper half of the flower unlike the lower half. the left and right halves tend to be mirror images of each other.

Pollination and fertilization

- Allogamy – cross pollination, when one plant pollinates another plant

- Anemophilous – wind pollinated.

- Autogamy – self-pollination, when the flowers of the same plant pollinate flowers on the same plant or themselves.

- Cantharophilous – beetle pollinated

- Chiropterophilous – bat pollinated.

- Cleistogamous – self-pollination of a flower that does not open.

- Dichogamy – Flowers that cannot pollinate themselves because pollen is produced at a time when the stigmas are not receptive of pollen.

- Entomophilous – insect pollinated.

- Hydrophilous – Water pollinated, pollen is moved in water from one flower to the next.

- Malacophilous – pollinated by snails and slugs.

- Ornithophilous – pollinated by birds.

- Pollination – the movement of pollen from the anther to the stigma.

- Protandrous – when pollen is produced and shed before the carpels are mature.

- Progynous – when the carpels mature before the stamens produce pollen.

Embryo development

- Antipodal cell –

- Chalazal –

- Coleoptile – protective sheathe on SAM

- Coleorhiza – protecting layer of a seed

- Cotyledon – 'Seed leaves' (First leaves sprouted – in a dicot, there are two cotyledons in a seedling)

- Diploid

- Double fertilization –

- Embryo –

- Embryo sac –

- Endosperm –

- Filiform apparatus –

- Germination –

- Plumule —the part of an embryo that give rise to the shoot system of a plant

- Polar nuclei –

- Radicle – Initial root-determined cells (Root apical meristem)

- Scutellum –

- Synergid –

- Tegmen –

- Testa – the seed coat; develops from the integuments after fertilization.[24]

- Sarcotesta – a fleshy seed coat

- Sclerotesta – a hard seed coat

- Triploid –

- Xenia – the effect of pollen on seeds and fruit

- Zygote –

Fruits and seeds

Fruits are the matured ovary of seed bearing plants and they include the contents of the ovary, which can be floral parts like the receptacle, involucre, calyx and others that are fused to it. Fruits are often used to identify plant taxa and help to place the species in the correct family or differentiate different groups within the same family.

Terms for fruits

- Accessory structures – parts of fruits that do not form from the ovary.

- Beak – normally the slender elongated end of a fruit, typically a persistent style-base.

- Circumscissile – a type of fruit dehiscences were the top of the fruit falls away like a lid or covering.

- Dehiscent – the way a fruit openings and releases its contents, normally in a regular and distinctive fashion.

- Endocarp – includes the wall of the seed chamber, the inner part of the pericarp.

- Exocarp – the pericarp's outer part.

- Fleshy – soft and juicy.

- Indehiscent – fruits that do not have specialized structures for opening and releasing the seeds, they remain closed after the seeds ripen and are opened by animals, weathering, fire or other external means.

- Mesocarp – the middle layer of the pericarp.

- Pericarp – the body of the fruit from its outside surface to the chamber were the seeds are, including the outside skin of the fruit and the inside lining of the seed chamber.

- Suture – the seam along which the fruit opens, normally in most fruits it is where the carpel or carpels are fused together.

- Valve – one of the segments of the capsule.

Fruit types

Fruits are divided into different types depending on how they form, were or how they open and what parts they are composed of.

- Achaenocarp – see achene.

- Achene – dry indehiscent fruit, they have one seed and form from a single carpel, the seed is distinct from the fruit wall.

- Caryopsis – the pericarp and seed are fused together, the fruit of many grasses.[26]

- Drupe – outer fleshy part surrounds a shell with a seed inside.

- Pod (seedpod) – a dry dehiscent fruit containing many seeds.[24] Examples include follicles, dehiscent capsules, and many but not all legumes.

- Nut – a fruit formed from a pistil with multiple carpels and having a woody covering. e.g. hickory, pecan, and oak.

- Nutlet – A small nut.

- Pome – accessory fruit from one or more carpels, specific to the apple and some related genera in the family Rosaceae

- Samara – winged achene, e.g. maples.

- Utricle – a small inflated fruit with one seed that has thin walls. Fruits are usually one-seeded. Some species of amaranth.

Seedless reproduction

Pteridophytes

- Acrostichoid sorus – having several fused sori.

- Annulus – outer part of sporangium

- Elater –

- Indusium –

- Marginal –

- Peltate –

- Reniform –

- Sporophyll –

- Sorus / Sori – a group or cluster of sporangia borne abaxially on a fern frond.[25]

- Strobilus –

- Submarginal –

Bryophytes

Gametangium

- Acrandrous – used for moss species that have antheridia at the top of the stem.

- Acrocarpous – In mosses, bearing the sporophyte at the axis of the main shoot

- Acrogynous – In liverworts, the female sex organs terminate the main shoot

- Anacrogynous – In liverworts, female sex organs are produced by a lateral cell, thus the growth of the main shoot is indeterminate

- Androcyte –

- Androecium –male sex organ

- Androgynous – Monoicous, and producing both types of sex organs together.

- Antheridiophore – A specialised branch that bears the antheridia in the Marchantiales

- Antherozoid –

- Archegoniophore – A specialised branch that bears the archaegonia in the Marchantiales

- Autoicous – Produces male and female sex organs on the same plant but on separate inflorescences

- Bract –leaf is present below the flower

- Cladautoicous – Male and female inflorescences on separate branches of the same plant

- Dioicous – Having two forms of gametophyte, one form bearing antheridia and one form bearing archegonia.

- Gonioautoicous – Male is bud-like in the axil of a female branch

- Incubous – describing the arrangement of leaves of a liverwort, contrast with succubous

- Inflorescence –cluster of flower

- Involucre – A tube of thallus tissue that protects the archegonia

- Monoicous – Having a single form of gametophyte bearing both antheridia and archegonia, either together or on separate branches.

- Paraphyses – Sterile hairs surrounding the archegonia and antheridia

- Perianth – A protective tube that surrounds the archegonia, characterises the Jungermannialean liverworts

- Perichaetium – The cluster of leaves with the enclosed female sex organs

- Perigonium – The cluster of leaves with the enclosed male sex organs

- Pseudautoicous – Dwarf male plants growing on living leaves of female plants

- Pseudomonoicous –

- Pseudoperianth – An involucre that resembles a perianth, but is made of thallus tissue, and usually forms after the sporophyte develops

- Rhizautoicous – Male inflorescence attached to the female stem by rhizoids

- Succubous – describing the arrangement of leaves of a liverwort, contrast with incubous

- Synoicous – Male and female sex organs on the same gametophyte but are not clustered

Sporangium

- Amphithecium – The external cell layers of the developing sporangium of a bryophyte. (Note: this term is also used in the mycology of lichens.)

- Anisosporous – Anisospore production is a rare condition in dioecious bryophytes; meiosis produces two small spores that develop into male gametophytes and two larger spores that develop into female gametophytes; contrast Isosporous.

- Annulus – in mosses, cells with thick walls along the rim of the sporangium and were the peristome teeth are attached.

- Apophysis –

- Archesporium –

- Arthrodontous –

- Articulate –

- Astomous –

- Basal membrane –

- Calyptra –

- Capsule –

- Cleistocarpous –

- Columella –

- Dehisce –

- Diplolepidous –

- Divisural line –

- Elater – structures derived from the sporangium of liverworts that aid in spore dispersal

- Endostome –

- Endothecium –

- Epiphragm –

- Exostome –

- Exothecium –

- Foot –

- Gymnostomous –

- Haplolepidous –

- Haustorium –

- Hypophysis –

- Immersed –

- Indehiscent –

- Inoperculate –

- Isosporous – unlike anisosporous species, whether monoecious or dioecious, all spores are the same size.

- Nematodontous –

- Nurse cells –

- Operculate –

- Operculum –

- Oral –

- Peristome –

- Pseudoelater – structures derived from the sporangium of hornworts that aid in spore dispersal

- Seta –

- Stegocarpous –

- Stoma –

- Suboral –

- Tapetum –

- Trabecula –

- Valve –

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Rudall 2007.

- 1 2 Radford et al. 1974.

- 1 2 Bell 1991.

- ↑ Judd et al. 2007, Chapter 4. Structural and Biochemical Characters.

- ↑ Dickinson 1999.

- 1 2 3 Simpson 2011, Flowers p. 364.

- 1 2 Simpson 2011, Flower parts p. 364.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Simpson 2011, Flower parts p. 365.

- ↑ Simpson 2011, Flower sex and plant sex p. 365.

- ↑ FEIS 2015.

- ↑ College Botany, VOL-1, By HC Gangulee, KS Das, CT Dutta, revised by S Sen, published by New Central Book Agency Kolkata

- ↑ A textbook of BOTANY , Vol-2, by Bhattacharya, Hait and Ghosh, NCBA Kolkata

- ↑ A textbook of BOTANY , Vol-2, by Bhattacharya, Hait and Ghosh, NCBA Kolkata

- ↑ BOTANY For Degree Students, 6th edition, by AC Datta, Revised by TC Datta, Oxford University Press

- ↑ BOTANY For Degree Students, 6th edition, by AC Datta, Revised by TC Datta, Oxford University Press

- ↑ BOTANY For Degree Students, 6th edition, by AC Datta, Revised by TC Datta, Oxford University Press

- ↑ A textbook of BOTANY , Vol-2, by Bhattacharya, Hait and Ghosh, NCBA Kolkata

- ↑ BOTANY For Degree Students, 6th edition, by AC Datta, Revised by TC Datta, Oxford University Press

- ↑ A textbook of BOTANY , Vol-2, by Bhattacharya, Hait and Ghosh, NCBA Kolkata

- ↑ BOTANY For Degree Students, 6th edition, by AC Datta, Revised by TC Datta, Oxford University Press

- ↑ A textbook of BOTANY , Vol-2, by Bhattacharya, Hait and Ghosh, NCBA Kolkata

- ↑ Slee et al. 2006.

- ↑ Simpson 2011, Style position p. 378

- 1 2 3 Hickey & King 2000.

- 1 2 3 4 Hart 2011.

- ↑ Wickens 2001, Cereals p. 155.

Bibliography

General

- Wickens, G.E. (2001). Economic Botany: Principles And Practices. Dordrecht: Kluwer. ISBN 978-1-4020-2228-9. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

Systematics

- Radford, A. E; Dickinson, W. C.; Massey, J. R.; Bell, C. R. (1974). Vascular Plant Systematics. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-045309-5.

- Jones, Samuel B. (1986). Plant Systematics. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-032796-3.

- Simpson, Michael G. (2011). Plant Systematics. Academic Press. ISBN 0-08-051404-9.

- Singh, Gurcharan (2004). Plant Systematics: An Integrated Approach (3 ed.). Science Publishers. ISBN 1-57808-351-6. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- Judd, Walter S.; Campbell, Christopher S.; Kellogg, Elizabeth A.; Stevens, Peter F.; Donoghue, Michael J. (2007). Plant systematics: a phylogenetic approach. (1st ed. 1999, 2nd 2002) (3 ed.). Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-407-3. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

Anatomy and morphology

- Bell, A. D. (1991). Plant Form, an Illustrated Guide to Flowering Plant Morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854279-8. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- Weberling, Focko (1992). Morphology of Flowers and Inflorescences (trans. Richard J. Pankhurst). CUP Archive. ISBN 0-521-43832-2. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- Rudall, Paula J. (2007). Anatomy of flowering plants : an introduction to structure and development (3 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69245-8. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- Dickinson, Tim (1999). "Comparative morphology: heterotopy and "cruddophytes"". Dickinson Lab, Botany Department, University of Toronto. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- González, A.M.; Arbo, M.M. (2016). "Botánica Morfológica: Morfología de Plantas Vasculares" (in Spanish). Corrientes, Argentina: Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias, Universidad Nacional del Nordeste. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- "Fruit Anatomy". Department of Plant Sciences, College of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences, UC Davis. 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

Glossaries

- Chiang, Fernando; Mario Sousa, S; Mario Sousa, P. "Glosario Inglés-Español, Español-Inglés para Flora Mesoamericana". Missouri Botanical Gardens. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- "Fire Effects Information System Glossary". Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). USDA Forest Service. 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- Slee, AV; Brooker, MIH; Duffy, SM; West, JG (2006). "Glossary". Euclid: Eucalypts of Australia. Victoria, Australia: CSIRO. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- Hickey, Michael; King, Clive (2000). The Cambridge Illustrated Glossary of Botanical Terms. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79401-3. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

Dictionaries

- Font Quer, P.. (1953). Diccionario de Botánica, Ed. Labor, Barcelona, .

- Hart, G.T. (2011). Plants in literature and life : a wide-ranging dictionary of botanical terms. Victoria, BC: Friesen Press. ISBN 978-1-77067-441-7. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- Usher, George (1996). The Wordsworth Dictionary of Botany. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Reference. ISBN 1-85326-374-5.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Botanical diagrams. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to SVG Botanical diagrams. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Flower diagrams. |

.jpg)