Middlesex

| Middlesex | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County | |||||

| |||||

Middlesex within England in 1890 | |||||

| Area | |||||

| • 1801/1881 | 734 km2 (181,320 acres)[1] | ||||

| • 1911 | 601.8 km2 (148,701 acres)[2] | ||||

| • 1961 | 601.7 km2 (148,691 acres)[2] | ||||

| Area transferred | |||||

| • 1889 | Metropolitan parishes to County of London | ||||

| Population | |||||

| • 1801 | 818,129[1] | ||||

| • 1881 | 2,920,485[1] | ||||

| • 1911 | 1,126,465[2] | ||||

| • 1961 | 2,234,543[2] | ||||

| Density | |||||

| • 1801 | 11 inhabitants per hectare (4.5/acre) | ||||

| • 1881 | 40 inhabitants per hectare (16.1/acre) | ||||

| • 1911 | 19 inhabitants per hectare (7.6/acre) | ||||

| • 1961 | 37 inhabitants per hectare (15/acre) | ||||

| History | |||||

| • Preceded by | Kingdom of Essex | ||||

| • Origin | Middle Saxons | ||||

| • Created | In antiquity | ||||

| • Abolished | 1965 | ||||

| • Succeeded by |

Greater London Hertfordshire Surrey | ||||

| Status |

Ceremonial county (until 1965) Administrative county (1889–1965) | ||||

| Chapman code | MDX[notes 1] | ||||

| Government |

Middlesex Quarter Sessions (until 1889)[notes 2] Within The Metropolis: Metropolitan Board of Works (1855–1889) Middlesex County Council (1889–1965) | ||||

| • HQ | see text | ||||

| Subdivisions | |||||

| • Type |

Hundreds (ancient) Districts (1835–1965) | ||||

Middlesex (/ˈmɪdəlsɛks/, abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in south-east England. It is now entirely within the wider urbanised area of London. Its area is now also mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in other neighbouring ceremonial counties. It was established in the Anglo-Saxon system from the territory of the Middle Saxons, and existed as an official unit until 1965. The historic county includes land stretching north of the River Thames from 3 miles (5 km) east to 17 miles (27 km) west of the City of London with the rivers Colne and Lea and a ridge of hills as the other boundaries. The largely low-lying county, dominated by clay in its north and alluvium on gravel in its south, was the second smallest county by area in 1831.[3]

The City of London was a county in its own right from the 12th century and was able to exert political control over Middlesex. Westminster Abbey dominated most of the early financial, judicial and ecclesiastical aspects of the county.[4] As London grew into Middlesex, the Corporation of London resisted attempts to expand the city boundaries into the county, which posed problems for the administration of local government and justice. In the 18th and 19th centuries the population density was especially high in the southeast of the county, including the East End and West End of London. From 1855 the southeast was administered, with sections of Kent and Surrey, as part of the area of the Metropolitan Board of Works.[5] When county councils were introduced in England in 1889 about 20% of the area of Middlesex, along with a third of its population, was transferred to the new County of London and the remainder became an administrative county governed by the Middlesex County Council[6] that met regularly at the Middlesex Guildhall in Westminster, in the County of London. The City of London, and Middlesex, became separate counties for other purposes and Middlesex regained the right to appoint its own sheriff, lost in 1199.

In the interwar years suburban London expanded further, with improvement and expansion of public transport,[7] and the setting up of new industries. After the Second World War, the population of the County of London[8] and inner Middlesex was in steady decline, with high population growth continuing in the outer parts.[9] After a Royal Commission on Local Government in Greater London, almost all of the original area was incorporated into an enlarged Greater London in 1965, with the rest transferred to neighbouring counties.[10] Since 1965 various areas called Middlesex have been used for cricket and other sports. Middlesex was the former postal county of 25 post towns.

History

Toponymy

The name means territory of the middle Saxons and refers to the tribal origin of its inhabitants. The word is formed from the Anglo-Saxon, i.e. Old English, 'middel' and 'Seaxe'[11] (cf. Essex, Sussex and Wessex). In an 8th-century charter the region is recorded as Middleseaxon[12][12][13] and in 704 it is recorded as Middleseaxan.[14]

Etymology

The Saxons derived their name from seax, a kind of knife for which they were known. The seax has a lasting symbolic impact in the English counties of Essex and Middlesex, both of which feature three seaxes in their ceremonial emblem. Their names, along with those of Sussex and Wessex, contain a remnant of the word "Saxon".

Early settlement

There were settlements in the area of Middlesex that can be traced back thousands of years before the creation of a county.[15] Middlesex was formerly part of the Kingdom of Essex[16][17] It was recorded in the Domesday Book as being divided into the six hundreds of Edmonton, Elthorne, Gore, Hounslow (Isleworth in all later records),[18] Ossulstone and Spelthorne. The City of London has been self-governing since the thirteenth century and became a county in its own right, a county corporate.[notes 3] Middlesex also included Westminster, which also had a high degree of autonomy. Of the six hundreds, Ossulstone contained the districts closest to the City of London. During the 17th century it was divided into four divisions, which, along with the Liberty of Westminster, largely took over the administrative functions of the hundred. The divisions were named Finsbury, Holborn, Kensington and Tower.[19] The county had parliamentary representation from the 13th century. The title Earl of Middlesex was created twice, in 1622 and 1677, but became extinct in 1843.[20]

Economic development

The economy of the county was dependent on the City of London from early times and was primarily agricultural.[4] A variety of goods were provided for the City, including crops such as grain and hay, livestock and building materials. Recreation at day trip destinations such as Hackney, Islington, Highgate and Twickenham, as well as coaching, inn-keeping and sale of goods and services at daily shops and stalls to the considerable passing trade provided much local employment[21] and also formed part of the early economy. However, during the 18th century the inner parishes of Middlesex became suburbs of the City and were increasingly urbanised.[4] The Middlesex volume of John Norden's Speculum Britanniae (a chorography) of 1593 summarises:

This is plentifully stored, as it seemeth beautiful, with many fair and comely buildings, especially of the merchants of London, who have planted their houses of recreation not in the meanest places, which also they have cunningly contrived, curiously beautified with divers[e] devices, neatly decked with rare inventions, environed with orchards of sundry, delicate fruits, gardens with delectable walks, arbours, alleys and a great variety of pleasing dainties: all of which seem to be beautiful ornaments unto this country.[22]

Similarly Thomas Cox wrote in 1794:

We may call it almost all London, being chiefly inhabited by the citizens, who fill the towns in it with their country houses, to which they often resort that they may breathe a little sweet air, free from the fogs and smoke of the City.[23]

In 1803 Sir John Sinclair, president of the Board of Agriculture, spoke of the need to cultivate the substantial Finchley Common and Hounslow Heath (perhaps prophetic of the Dig for Victory campaign of World War II) and fellow Board member Middleton estimated that one tenth of the county, 17,000 acres (6,900 ha), was uncultivated common, capable of improvement.[24] However William Cobbett, in casual travel writing in 1822, said that "A more ugly country between Egham (Surrey) and Kensington would with great difficulty be found in England. Flat as a pancake, and until you come to Hammersmith, the soil is a nasty, stony dirt upon a bed of gravel. Hounslow Heath which is only a little worse than the general run, is a sample of all that is bad in soil and villainous in look. Yet this is now enclosed, and what they call 'cultivated'. Here is a fresh robbery of villages, hamlets, and farm and labourers' buildings and abodes."[25] Thomas Babington wrote in 1843, "An acre in Middlesex is worth a principality in Utopia"[26] which contrasts neatly with its agricultural description.

The building of radial railway lines from 1839 caused a fundamental shift away from agricultural supply for London towards large scale house building.[27] Tottenham, Edmonton and Enfield in the north developed first as working-class residential suburbs with easy access to central London. The line to Windsor through Middlesex was completed in 1848, and the railway to Potters Bar in 1850; and the Metropolitan and District Railways started a series of extensions into the county in 1878. Closer to London, the districts of Acton, Willesden, Ealing and Hornsey came within reach of the tram and bus networks, providing cheap transport to central London.[27]

After World War I, the availability of labour and proximity to London made areas such as Hayes and Park Royal ideal locations for the developing new industries.[27] New jobs attracted more people to the county and the population continued to rise, reaching a peak in 1951.

Governance

The Metropolis

By the 19th century, the East End of London had expanded to the eastern boundary with Essex, and the Tower division had reached a population of over a million.[1] When the railways were built, the north western suburbs of London steadily spread over large parts of the county.[7] The areas closest to London were served by the Metropolitan Police from 1829, and from 1840 the entire county was included in the Metropolitan Police District.[28] Local government in the county was unaffected by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, and civic works continued to be the responsibility of the individual parish vestries or ad hoc improvement commissioners.[29][30] In 1855, the parishes of the densely populated area in the south east, but excluding the City of London, came within the responsibility of the Metropolitan Board of Works.[5] Despite this innovation, the system was described by commentators at the time as one "in chaos".[6] In 1889, under the Local Government Act 1888, the metropolitan area of approximately 30,000 acres (120 km2) became part of the County of London.[20] The Act also provided that the part of Middlesex in the administrative county of London should be "severed from [Middlesex], and form a separate county for all non-administrative purposes".

The part of the County of London that had been transferred from Middlesex was divided in 1900 into 18 metropolitan boroughs,[31] which were merged in 1965 to form seven of the present-day inner London boroughs:

- Camden was formed from the metropolitan boroughs of Hampstead, Holborn and St Pancras

- Hackney was formed from the metropolitan boroughs of Hackney, Shoreditch and Stoke Newington

- Hammersmith (known as Hammersmith and Fulham from 1979) was formed from the metropolitan boroughs of Hammersmith and Fulham

- Islington was formed from the metropolitan boroughs of Finsbury and Islington

- Kensington and Chelsea was formed from the metropolitan boroughs of Chelsea and Kensington

- Tower Hamlets was formed from the metropolitan boroughs of Bethnal Green, Poplar and Stepney

- The City of Westminster was formed from the metropolitan boroughs of Paddington and St Marylebone and the City of Westminster.[5]

Extra-metropolitan area

Middlesex outside the metropolitan area remained largely rural until the middle of the 19th century and so the special boards of local government for various metropolitan areas were late in developing. Other than the Cities of London and Westminster, there were no ancient boroughs.[32] The importance of the hundred courts declined, and such local administration as there was divided between "county business" conducted by the justices of the peace meeting in quarter sessions, and the local matters dealt with by parish vestries. As the suburbs of London spread into the area, unplanned development and outbreaks of cholera forced the creation of local boards and poor law unions to help govern most areas; in a few cases parishes appointed improvement commissioners.[33] In rural areas, parishes began to be grouped for different administrative purposes. From 1875 these local bodies were designated as urban or rural sanitary districts.[34]

Following the Local Government Act 1888, the remaining county came under the control of Middlesex County Council except for the parish of Monken Hadley, which became part of Hertfordshire.[35] The area of responsibility of the Lord Lieutenant of Middlesex was reduced accordingly. Middlesex did not contain any county boroughs, so the county and administrative county (the area of county council control) were identical.

The Local Government Act 1894 divided the administrative county into four rural districts and thirty-one urban districts, based on existing sanitary districts. One urban district, South Hornsey, was an exclave of Middlesex within the County of London until 1900, when it was transferred to the latter county.[36] The rural districts were Hendon, South Mimms, Staines and Uxbridge. Because of increasing urbanisation these had all been abolished by 1934.[10] Urban districts had been created, merged, and many had gained the status of municipal borough by 1965. The districts as at the 1961 census were:[9]

|

After 1889 the growth of London continued, and the county became almost entirely filled by suburbs of London, with a big rise in population density. This process was accelerated by the Metro-land developments, which covered a large part of the county.[37] The expanding urbanisation had, however, been foretold in 1771 by Tobias Smollett in The Expedition of Humphry Clinker, in which it is said:

Pimlico and Knightsbridge are almost joined to Chelsea and Kensington, and, if this infatuation continues for half a century, then, I suppose, the whole county of Middlesex will be covered in brick.[38]

Public transport in the county, including the extensive network of trams,[39] buses and the London Underground came under control of the London Passenger Transport Board in 1933[40] and a New Works Programme was developed to further enhance services during the 1930s.[7] Partly because of its proximity to the capital, the county had a major role during the Second World War. The county was subject to aerial bombardment and contained various military establishments, such as RAF Uxbridge and RAF Heston, which were involved in the Battle of Britain.[41]

County town

Middlesex arguably never, and certainly not since 1789, had a single, established county town. London could be regarded as its county town for most purposes[27] and provided different locations for the various, mostly judicial, county purposes. The County Assizes for Middlesex were held at the Old Bailey in the City of London.[4] Until 1889, the High Sheriff of Middlesex was chosen by the City of London Corporation. The sessions house for the Middlesex Quarter Sessions was at Clerkenwell Green from the early 18th century. The quarter sessions at the former Middlesex Sessions House performed most of the limited administration on a county level until the creation of the Middlesex County Council in 1889. New Brentford was first promulgated as the county town in 1789, on the basis that it was where elections of Knights of the Shire (or Members of Parliament) were held from 1701.[20][42] Thus a traveller's and historian's London regional summary of 1795 states that (New) Brentford was "considered as the county-town; but there is no town-hall or other public building".[43] Middlesex County Council took over at the Guildhall in Westminster, which became the Middlesex Guildhall. In the same year, this location was placed into the new County of London, and was thus outside the council's area of jurisdiction.

Arms of Middlesex County Council

Coats of arms were attributed by the mediaeval heralds to the Kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. That assigned to the Kingdom of the Middle and East Saxons depicted three "seaxes" or short notched swords on a red background. The seaxe was a weapon carried by Anglo-Saxon warriors, and the term "Saxon" may be derived from the word.[44][45] These arms became associated with the two counties that approximated to the kingdom: Middlesex and Essex. County authorities, militia and volunteer regiments associated with both counties used the attributed arms.

In 1910, it was noted that the county councils of Essex and Middlesex and the Sheriff's Office of the County of London were all using the same arms. Middlesex County Council decided to apply for a formal grant of arms from the College of Arms, with the addition of an heraldic "difference" to the attributed arms. Colonel Otley Parry, a Justice of the Peace for Middlesex and author of a book on military badges, was asked to devise an addition to the shield. The chosen addition was a "Saxon Crown", derived from the portrait of King Athelstan on a silver penny of his reign, stated to be the earliest form of crown associated with any English sovereign. The grant of arms was made by letters patent dated 7 November 1910.[46][47][48]

|

The arms of the Middlesex County Council were blazoned: Gules, three seaxes fessewise points to the sinister proper, pomels and hilts and in the centre chief point a Saxon crown or. |

The undifferenced arms of the Kingdom were eventually granted to Essex County Council in 1932.[49] Seaxes were also used in the insignia of many of the boroughs and urban districts in the county, while the Saxon crown came to be a common heraldic charge in English civic arms.[50][51] On the creation of the Greater London Council in 1965 a Saxon crown was introduced in its coat of arms.[52] Seaxes appear in the arms of several London borough councils and of Spelthorne Borough Council, whose area was in Middlesex.[53][54]

Creation of Greater London

The population of inner London (then the County of London) had been in decline as more residents moved into the outer suburbs since its creation in 1889, and this continued after the Second World War.[8] In contrast, the population of Middlesex had increased steadily during that period.[55] From 1951 to 1961 the population of the inner districts of the county started to fall, and the population grew only in eight of the suburban outer districts.[9] According to the 1961 census, Ealing, Enfield, Harrow, Hendon, Heston & Isleworth, Tottenham, Wembley, Willesden and Twickenham had each reached a population greater than 100,000, which would normally have entitled each of them to seek county borough status. If this status were to be granted to all those boroughs it would mean that the population of the administrative county of Middlesex would be reduced by over half, to just under one million.

Evidence submitted to the Royal Commission on Local Government in Greater London included a recommendation to divide Middlesex into two counties of North Middlesex and West Middlesex.[27] However, the commission instead proposed abolition of the county and merging of the boroughs and districts. This was enacted by Parliament as the London Government Act 1963, which came into force on 1 April 1965.

The Act abolished the administrative counties of Middlesex and London.[56] The Administration of Justice Act 1964 abolished the Middlesex magistracy and lieutenancy, and altered the jurisdiction of the Central Criminal Court. In April 1965, nearly all of Middlesex became part of Greater London, under the control of the Greater London Council, and formed the new outer London boroughs of Barnet (part only), Brent, Ealing, Enfield, Haringey, Harrow, Hillingdon, Hounslow and Richmond upon Thames (part only).[57] The remaining areas were Potters Bar Urban District, which became part of Hertfordshire, and Sunbury-on-Thames Urban District and Staines Urban District, which became part of Surrey.[10] Following the changes, local acts of Parliament relating to Middlesex were henceforth to apply to the entirety of the nine "North West London Boroughs".[58] In 1974, the three urban districts that had been transferred to Hertfordshire and Surrey were abolished and became the districts of Hertsmere (part only) and Spelthorne respectively.[59] In 1995 the village of Poyle was transferred from Spelthorne to the Berkshire borough of Slough.[60] Additionally, since 1965 the Greater London boundary to the west and north has been subject to several small changes.[61][62]

Geography

The county lay within the London Basin[63] and the most significant feature was the River Thames, which formed the southern boundary. The River Lea and the River Colne formed natural boundaries to the east and west. The entire south west boundary of Middlesex followed a gently descending meander of the Thames without hills. In many places "Middlesex bank" is more accurate than "north bank" — for instance at Teddington the river flows north-westward, so the left (Middlesex) bank is the south-west bank.[notes 4] In the north, the boundary ran along a WSW/ENE aligned ridge of hills broken by Barnet or 'Dollis' valleys. (South of the boundary, these feed into the Welsh Harp Lake or Brent Reservoir which becomes the River Brent).[notes 5] This formed a long protrusion of Hertfordshire into the county.[64] The county was thickly wooded,[63] with much of it covered by the ancient Forest of Middlesex. The highest point was the High Road by Bushey Heath at 502 feet (153 m),[65] which is now one of the highest points in London.[66]

Legacy

"Middlesex" is used in the names of organisations based in the area such as Middlesex County Cricket Club,[67] the Middlesex Cricket Board and Middlesex University.[68] (The last two of these were formed some time after Middlesex was abolished as an administrative county.) There is a Middlesex County Football Association, and two teams that are now within Surrey, Staines Town and Ashford Town (Middlesex) as well as Potters Bar Town in Hertfordshire,[69] compete in the Middlesex County Cup.[70] Sir John Betjeman, a native of North London and Poet Laureate, published several poems about Middlesex and the suburban experience. Many were featured in the televised readings Metroland.[71]

| “ | Dear Middlesex, dear vanished country friend,

Your neighbour, London, killed you in the end. |

” |

| — Contrasts: Marble Arch to Edgware – A Lament, John Betjeman (1968)[72] | ||

As part of a 2002 marketing campaign, the plant conservation charity Plantlife chose the wood anemone as the county flower. In 2003, an early day motion with two signatures noted that 16 May is the anniversary of the Battle of Albuera and in recent years has been celebrated as "Middlesex Day", commemorating the valiant efforts of the Middlesex Regiment (the "Die-hards") in that battle. The idea is to recognise and celebrate the historic county.[73] On its creation in 1965, Greater London was divided into five commission areas for the administration of justice. One was named "Middlesex" and consisted of the boroughs of Barnet, Brent, Ealing, Enfield, Haringey, Harrow, Hillingdon and Hounslow.[74] This was abolished on 1 July 2003.[75] For genealogical research it was assigned Chapman code MDX, except for the City of London which was assigned code LND. The Royal Mail continues to designate the Surrey towns of Staines-upon-Thames, Sunbury-on-Thames and Ashford as Middlesex.

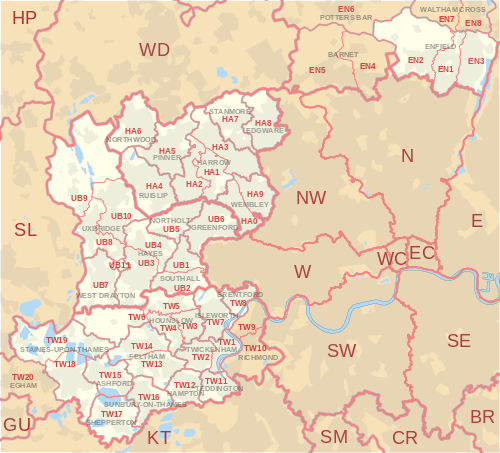

Former postal county

Middlesex (abbreviated Middx) was a former postal county.[76] This was an element of postal addressing in routine use until 1996, intended to avoid confusion between post towns, and no longer required for the routing of the mail.[77] The postal county did not match the boundaries of Middlesex because of the presence of the London postal district, which stretched into the county to include Tottenham, Willesden, Hornsey and Chiswick.[78] Addresses in this area included "LONDON" but did not include a county. In 1965 Royal Mail retained the postal county because it would have been too costly to amend addresses throughout Greater London.[79] Exceptionally, the Potters Bar post town was transferred to Hertfordshire. Geographically the postal county consisted of two unconnected areas, 6 miles (10 km) apart. These were the smaller area around Enfield and the larger area to the west.[80] It comprised 25 post towns:

| Postcode area | Post towns |

|---|---|

| EN (part) | ENFIELD; POTTERS BAR (until 1965) |

| HA | EDGWARE, HARROW, NORTHWOOD, PINNER, RUISLIP, STANMORE, WEMBLEY |

| TW (part) | ASHFORD, BRENTFORD, FELTHAM, HAMPTON, HOUNSLOW†, ISLEWORTH, SHEPPERTON, STAINES, SUNBURY-ON-THAMES, TEDDINGTON, TWICKENHAM† |

| UB | GREENFORD, HAYES, NORTHOLT, SOUTHALL, UXBRIDGE, WEST DRAYTON |

† = postal county was not required

The postal county had many border inconsistencies where its constituent post towns encroached on neighbouring counties, such as the villages of Denham in Buckinghamshire, Wraysbury in Berkshire and Eastbury in Hertfordshire which were respectively in the post towns of Uxbridge, Staines and Northwood and therefore in the postal county of Middlesex. Egham Hythe, Surrey also had postal addresses of Staines, Middlesex. Conversely, Hampton Wick was conveniently placed in Kingston, Surrey with its sorting offices just across the river.[81] Nearby Hampton Court Palace has a postal address of East Molesey, therefore associating it with Surrey.[82]

The Enfield post town in the EN postcode area was in the former postal county. All post towns in the HA postcode area and UB postcode area were in the former postal county. Most of the TW postcode area was in the former postal county.

See also

- List of Lord Lieutenants of Middlesex

- Custos Rotulorum of Middlesex - List of Keepers of the Rolls

- List of High Sheriffs of Middlesex

- Middlesex (UK Parliament constituency) - Historical list of MPs for the Middlesex constituency

Notes and references

- Notes

- ↑ Historic boundaries excluding the City of London, which is code LND

- ↑ The Middlesex Quarter Sessions had jurisdiction in Westminster, but not the Tower Liberty

- ↑ The City of London continues to be a county distinct from Greater London.

- ↑ County descriptions are standard in boat racess, and the historic county descriptions of the respective sides of the river are still used during the famous University Boat Race and the professional and amateur Head of the River Race.

- ↑ The Dollis Valley greenwalk follows this steep upper valley of the Dollis Brook

- References

- 1 2 3 4 "Table of population, 1801-1901". A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 22. 1911. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Great Britain Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, Middlesex population (area and density). Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Great Britain Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, 1831 Census population. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 The Proceedings of the Old Bailey - Rural Middlesex. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- 1 2 3 Saint, A., Politics and the people of London: the London County Council (1889-1965), (1989)

- 1 2 Barlow, I., Metropolitan Government, (1991)

- 1 2 3 Wolmar, C., The Subterranean Railway, (2004)

- 1 2 Great Britain Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, County of London population. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- 1 2 3 Great Britain Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, Census 1961: Middlesex population. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- 1 2 3 Great Britain Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, Middlesex. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Mills 2001, p. 151

- 1 2 Middlesex - The jubilee of the County Council, C W Radcliffe, Evans Brothers, 1939

- ↑ Tuican Hom, http://www.twickenham-museum.org.uk/detail.asp?ContentID=12, retrieved 30 March 2012

- ↑ Stevenson, Bruce (1972). Middlesex. p. 13.

- ↑ Twickenham Museum, http://www.twickenham-museum.org.uk/detail.asp?ContentID=364, retrieved 30 March 2012

- ↑ Keightley, A., The History of England, (1840)

- ↑ "County of Middlesex Trust, Historical Facts". County of Middlesex Trust. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ↑ "The hundred of Isleworth". A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 3. 1962. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Great Britain Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, Ossulstone hundred. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- 1 2 3 Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911 Edition

- ↑ Robbins, Michael (2003) [1953]. Middlesex. Chichester: Phillimore. p. 189. ISBN 9781860772696.

- ↑ S.G. Mendyk, Speculum Britanniae: regional study, antiquarianism, and science in Britain to 1700, 1989.

- ↑ Magna Britannia et Hibernia Antiqua et Nova Thomas Cox, E. Nutt (publisher) (1720) Vol iii. p.1

- ↑ Robbins, Michael (2003) [1953]. Middlesex. Chichester: Phillimore. p. 38. ISBN 9781860772696.

- ↑ Rural Rides Volume i. THROUGH HAMPSHIRE, BERKSHIRE, SURREY, AND SUSSEX, BETWEEN 7 October AND 1 December 1822 (ed. Everyman) William Cobbett, p 124

- ↑ Robbins, Michael (2003) [1953]. Middlesex. Chichester: Phillimore. p. xiii and 28. ISBN 9781860772696.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Greater London Group (July 1959). Memorandum of Evidence to The Royal Commission on Local Government in Greater London. London School of Economics.

- ↑ Order in Council enlarging the Metropolitan Police District (SI 1840 5001)

- ↑ Local Government Areas 1834 -1945, V D Lipman, Oxford, 1949

- ↑ Joseph Fletcher, The Metropolis; its Boundaries, Extent, and Divisions for Local Government in Journal of the Statistical Society of London, Vol. 7, No. 2. (June 1844), pp. 103-143.

- ↑ http://www.middlesex-heraldry.org.uk/publications/seaxe/SeaxeOS06-198501.pdf The Seaxe, Sixth Issue, January 1985, page 4

- ↑ London Metropolitan Archives - A Brief Guide to the Middlesex Sessions Records, (2009). Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- ↑ Robbins, Michael (2003) [1953]. Middlesex. Chichester: Phillimore. pp. 199–205. ISBN 9781860772696.

- ↑ Royston Lambert, Central and Local Relations in Mid-Victorian England: The Local Government Act Office, 1858-71, Victorian Studies, Vol. 6, No. 2. (Dec. 1962), pp. 121-150.

- ↑ Great Britain Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, Monken Hadley. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Frederic Youngs, Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England, Vol.I : Southern England, London, 1979

- ↑ Royston, J., Revisiting the Metro-Land Route, Harrow Times. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ "The Miscellaneous Works Of Tobias Smollett". Google Books. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ↑ Reed, J., London Tramways, (1997)

- ↑ Office of Public Sector Information - London Passenger Transport Act 1933 (as amended). Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Royal Air Force - Battle of Britain Campaign Diary. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ "Ealing and Brentford: Growth of Brentford". A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 7. 1982. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ "Brentford". The Environs of London: volume 2: County of Middlesex. 1795. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Doherty, F., The Anglo Saxon Broken Back Seax. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Online Etymology Dictionary - Saxon. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ "Armorial bearings of Middlesex", The Times. London. 7 November 1910.

- ↑ The Book of Public Arms, A.C. Fox-Davies, 2nd edition, London, 1915

- ↑ Civic Heraldry of England and Wales, W.C. Scott-Giles, 2nd edition, London, 1953

- ↑ Civic Heraldry of England and Wales - Essex County Council. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Civic Heraldry of England and Wales - Middlesex (obsolete). Retrieved 20 February 2008

- ↑ C W Scott-Giles, Royal and Kindred Emblems, Civic Heraldry of England and Wales, 2nd edition, London, 1953, p.11

- ↑ Civic Heraldry of England and Wales - Greater London Council. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Civic Heraldry of England and Wales - Spelthorne Borough Council. Retrieved 20 February 2008

- ↑ Civic Heraldry of England and Wales - Greater London. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Great Britain Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, Middlesex population. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ London Government Act 1963, Section 3: (1) As from 1 April 1965—

(a) no part of Greater London shall form part of any administrative county, county district or parish;

(b) the following administrative areas and their councils (and, in the case of a borough, the municipal corporation thereof) shall cease to exist, that is to say, the counties of London and Middlesex, the metropolitan boroughs, and any existing county borough, county district or parish the area of which falls wholly within Greater London;

The new enlarged administration became known as the Greater London Council or its acronym, the GLC. The former separate (joint) fire and ambulance service of Middlesex, the second largest in Britain after London was largely absorbed into enlarged London organisations under the newly formed GLC, the exception being those areas moving into Surrey and Hertfordshire. (c) the urban district of Potters Bar shall become part of the county of Hertfordshire;

(d) the urban districts of Staines and Sunbury-on-Thames shall become part of the county of Surrey.

Section 89: (1) In this Act, except where the context otherwise requires, the following expressions have the following meanings respectively, that is to say—

'county' means an administrative county; - ↑ Office of Public Sector Information - London Government Act 1963 (as amended) Archived 19 May 2011 at WebCite. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ The Local Law (North West London Boroughs) Order 1965 (S.I. 1965 No. 533)

- ↑ The English Non-metropolitan Districts (Definition) Order 1972 (SI 1972/2038)

- ↑ Office of Public Sector Information - Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Surrey (County Boundaries) Order 1994 Archived 2 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Office of Public Sector Information - The Heathrow Airport (County and London Borough Boundaries) Order 1993. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- ↑ Office of Public Sector Information - The Greater London and Surrey (County and London Borough Boundaries) (No. 4) Order 1993. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- 1 2 Natural England - London Basin Natural Area. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- ↑ "The Physique of Middlesex". A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 1. 1969. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ The Mountains of England and Wales - Historic County Tops. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ The Mountains of England and Wales - London Borough Tops. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ↑ Middlesex County Cricket Club. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Middlesex University - About Us: Our History. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Potters Bar Town F.C. - Fixtures. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Mitoo - 2006–2007 Season: Middlesex County Football Association. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Wilson, A., Betjeman, (2006)

- ↑ John Betjeman; Stephen Games (2010). Betjeman's England. Hachette UK. ISBN 9781848543805.

- ↑ Randall, J., Early Day Motion 13 May 2003. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Administration of Justice Act 1964 (1964 C. 42)

- ↑ Office of Public Sector Information - The Commission Areas (Greater London) Order 2003 (Statutory Instrument 2003 No. 640). Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Royal Mail - PAF Digest Issue 6.0. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ Royal Mail 2004, p. 9

- ↑ HMSO, Names of Street and Places in the London Postal area, (1930). Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ "G.P.O. To Keep Old Names. London Changes Too Costly.". The Times. London. 12 April 1966.

- ↑ Geographers' A-Z Map Company 2008, p. 1

- ↑ Paul Waugh (29 May 2003). "Property boom fuels calls to reform 'postcode lottery'". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- ↑ "Hampton Court: How to find us". Historic Royal Palaces. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- Bibliography

- Geographers' A-Z Map Company (2008), London Postcode and Administrative Boundaries (6 ed.), Geographers' A-Z Map Company, ISBN 978-1-84348-592-6

- Mills, A.D. (2001), Dictionary of London Place Names, Oxford, ISBN 0-19-280106-6

- Page, William (Edr.) (1911), A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 2, Victoria County History, British History Online

- Royal Mail (2004), Address Management Guide (4 ed.), Royal Mail Group

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Middlesex. |

- Victoria County History of Middlesex

- Map of Middlesex on Wikishire

- Historic boundary as layer for Google Earth

- Article on Middlesex from Encyclopædia Britannica

- Maps of Middlesex subdivisions: Edmonton, Elthorne, Gore, Isleworth and Spelthorne

- Middlesex and West London Photo Galleries

| Neighbouring counties (1889-1965) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Buckinghamshire | Hertfordshire | Herts/Essex |  |

| Berkshire | |

Essex | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Surrey | Surrey | London | ||

Coordinates: 51°30′N 0°25′W / 51.500°N 0.417°W