Carrion crow

| Carrion crow | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scavenging on a beach in Dorset, England | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Corvidae |

| Genus: | Corvus |

| Species: | C. corone |

| Binomial name | |

| Corvus corone Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| |

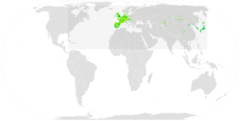

| Carrion crow range Year-Round Range Summer Range Winter Range | |

The carrion crow (Corvus corone) is a passerine bird of the family Corvidae and the genus Corvus which is native to western Europe and eastern Asia.

Taxonomy and systematics

The carrion crow was one of the many species originally described by Linnaeus in his 18th century work Systema Naturae and it still bears its original name of Corvus corone.[2] The binomial name is derived from the Latin Corvus, "Raven",[3] and Greek korone/κορωνη, "crow".[4]

The hooded crow, formerly regarded as a subspecies, has been split off as a separate species, and there is some discussion whether the Eastern carrion crow (C. c. orientalis) is distinct enough to warrant specific status; the two taxa are well separated, and it has been proposed they could have evolved independently in the wetter, maritime regions at the opposite ends of the Eurasian landmass.[5]

Description

The plumage of carrion crow is black with a green or purple sheen, much greener than the gloss of the rook. The bill, legs and feet are also black. It can be distinguished from the common raven by its size (48–52 cm or 19 to 20 inches in length as compared to an average of 63 centimetres (25 inches) for ravens) and from the hooded crow by its black plumage. The carrion crow has a wingspan of 84–100 cm or 33 to 39 inches and weighs 400-600 grams.

There is frequent confusion between the carrion crow and the rook, another black corvid found within its range. The beak of the crow is stouter and in consequence looks shorter, and whereas in the adult rook the nostrils are bare, those of the crow are covered at all ages with bristle-like feathers. As well as this, the wings of a carrion crow are proportionally shorter and broader than those of the rook when seen in flight.[6]

Distribution and genetic relationship to hooded crows

The carrion crow (Corvus corone) and hooded crow (Corvus cornix, including its slightly larger allied form or race C. c. orientalis) are two very closely related species[7] whose geographic distributions across Europe are illustrated in the accompanying diagram. It is believed that this distribution might have resulted from the glaciation cycles during the Pleistocene, which caused the parent population to split into isolates which subsequently re-expanded their ranges when the climate warmed causing secondary contact.[8][9]

Poelstra and coworkers sequenced almost the entire genomes of both species in populations at varying distances from the contact zone to find that the two species were genetically identical, both in their DNA and in its expression (in the form of mRNA), except for the lack of expression of a small portion (<0.28%) of the genome (situated on avian chromosome 18) in the hooded crow, which imparts the lighter plumage colouration on its torso.[8] Thus the two species can viably hybridize, and occasionally do so at the contact zone, but the all-black carrion crows on the one side of the contact zone mate almost exclusively with other all-black carrion crows, while the same occurs among the hooded crows on the other side of the contact zone.

It is therefore clear that it is only the outward appearance of the two species that inhibits hybridization.[8][9] The authors attribute this to assortative mating (rather than to ecological selection), the advantage of which is not clear, and it would lead to the rapid appearance of streams of new lineages, and possibly even species, through mutual attraction between mutants. Unnikrishnan and Akhila propose, instead, that koinophilia is a more parsimonious explanation for the resistance to hybridization across the contact zone, despite the absence of physiological, anatomical or genetic barriers to such hybridization.[8] The carrion crow is also found in the mountains and forests of Japan and also in the cities of Japan.[10]

Behaviour and ecology

The rook is generally gregarious and the crow solitary, but rooks occasionally nest in isolated trees, and crows may feed with rooks; moreover, crows are often sociable in winter roosts. The most distinctive feature is the voice. The rook has a high-pitched kaaa, but the crow's guttural, slightly vibrant, deeper croaked kraa is distinct from any note of the rook.

The carrion crow is noisy, perching on the top of a tree and calling three or four times in quick succession, with a slight pause between each series of croaks. The wing-beats are slower, more deliberate than those of the rook.

Carrion crows can become tame near humans, and can often be found near areas of human activity or habitation including cities, moors, woodland, sea cliffs and farmland[11] where they compete with other social birds such as gulls and ducks for food in parks and gardens.

Like all corvids, carrion crows are highly intelligent, and are among the most intelligent of all animals.[12]

Diet

Though an eater of carrion of all kinds, the carrion crow will eat insects, earthworms, grain, fruits, seeds, small mammals, amphibians, scraps and will also steal eggs. Crows are scavengers by nature, which is why they tend to frequent sites inhabited by humans in order to feed on their household waste. Crows will also harass birds of prey or even foxes for their kills. Crows actively hunt and occasionally co-operate with other crows to make kills.

Crows have become highly skilled at adapting to urban environments. In a Japanese city, carrion crows have discovered how to eat nuts that they usually find too hard to tackle. One method is to drop the nuts from height on to a hard road in the hope of cracking it. Some nuts are particularly tough, so the crows drop the nuts among the traffic. That leaves the problem of eating the bits without getting run over, so some birds wait by pedestrian crossings and collect the cracked nuts when the lights turn red.[13]

Nesting

The bulky stick nest is usually placed in a tall tree, but cliff ledges, old buildings and pylons may be used as well. Nests are also occasionally placed on or near the ground. The nest resembles that of the common raven, but is less bulky. The 3 to 4 brown-speckled blue or greenish eggs are incubated for 18–20 days by the female alone, who is fed by the male. The young fledge after 29–30 days.[14]

It is not uncommon for an offspring from the previous years to stay around and help rear the new hatchlings. Instead of seeking out a mate, it looks for food and assists the parents in feeding the young.[15]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Corvus corone". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ (in Latin) Linnaeus, C (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 105. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015.

C. atro-caerulescens, cauda rotundata: rectricibus acutis.

- ↑ "Corvus". Merriam-Webster online. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- ↑ Liddell & Scott (1980). Greek-English Lexicon, Abridged Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ↑ Madge, Steve & Burn, Hilary (1994): Crows and jays: a guide to the crows, jays and magpies of the world. A&C Black, London. ISBN 0-7136-3999-7

- ↑ Holden, Peter (2012). RSPB Handbook Of British Birds. p. 274. ISBN 978 1 4081 2735 3.

- ↑ Parkin, David T. (2003). "Birding and DNA: species for the new millennium". Bird Study. 50 (3): 223–242. doi:10.1080/00063650309461316.

- 1 2 3 4 Poelstra, Jelmer W.; Vijay, Nagarjun; Bossu, Christen M.; et al. (2014). "The genomic landscape underlying phenotypic integrity in the face of gene flow in crows". Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 344 (6190): 1410–1414. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 24948738. doi:10.1126/science.1253226.

- 1 2 de Knijf, Peter (2014). "How carrion and hooded crows defeat Linnaeus's curse". Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 344 (6190): 1345–1346. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 24948724. doi:10.1126/science.1255744. Further reading:

- ↑ Attenborough. D. 1998. The Life of Birds. pp.295 BBC ISBN 0563-38792-0

- ↑ Holden, Peter (2012). RSPB Handbook Of British Birds. p. 274. ISBN 978 1 4081 2735 3.

- ↑ Prior H.; et al. (2008). De Waal, Frans, ed. "Mirror-Induced Behavior in the Magpie (Pica pica): Evidence of Self-Recognition" (PDF). PLoS Biology. Public Library of Science. 6 (8): e202. PMC 2517622

. PMID 18715117. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060202. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

. PMID 18715117. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060202. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-21. - ↑ "Red Light Runners". BBC. 2007.

- ↑ British Trust for Ornithology (2005) Nest Record Scheme data.

- ↑ Baglione, V.; Marcos, J. M.; Canestrari, D.; Ekman, J. (2002). "Direct fitness benefits of group living in a complex cooperative society of carrion crows, Corvus corone corone". Animal Behaviour. 64 (6): 887–893. doi:10.1006/anbe.2002.2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Corvus corone. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Corvus corone |

- Carrion crow call.

- Carrion crow videos, photos & sounds on the Internet Bird Collection.

- Photo of profile.

- Image of the skull.

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 3.4 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze.

- HOME of the corvus corone corone.