Copenhagen criteria

| European Union |

This article is part of a series on the |

Policies and issues

|

The Copenhagen criteria are the rules that define whether a country is eligible to join the European Union. The criteria require that a state has the institutions to preserve democratic governance and human rights, has a functioning market economy, and accepts the obligations and intent of the EU.

These membership criteria were laid down at the June 1993 European Council in Copenhagen, Denmark, from which they take their name. Excerpt from the Copenhagen Presidency conclusions:[2]

Membership requires that candidate country has achieved stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights, respect for and protection of minorities, the existence of a functioning market economy as well as the capacity to cope with competitive pressure and market forces within the Union. Membership presupposes the candidate's ability to take on the obligations of membership including adherence to the aims of political, economic and monetary union.

Most of these elements have been clarified over the last decade by legislation of the European Council, the European Commission and the European Parliament, as well as by the case law of the European Court of Justice and the European Court of Human Rights. However, there are sometimes slightly conflicting interpretations in current member states—some examples of this are given below.

European Union membership criteria

During the negotiations with each candidate country, progress towards meeting the Copenhagen criteria is regularly monitored. On the basis of this, decisions are made as to whether and when a particular country should join, or what actions need to be taken before joining is possible.

The European Union Membership criteria are defined by the three documents:

- The 1992 Treaty of Maastricht (Article 49)

- The declaration of the June 1993 European Council in Copenhagen, i.e., Copenhagen criteria—describing the general policy in more details

- political

- economic

- legislative

- Framework for negotiations with a particular candidate state

- specific and detailed conditions

- statement stressing that the new member cannot take its place in the Union until it is considered that the EU itself has enough "absorption capacity" for this to happen.

When agreed in 1993, there was no mechanism for ensuring that any country which was already an EU member state was in compliance with these criteria. However, arrangements have now been put in place to police compliance with these criteria, following the "sanctions" imposed against the Austrian government of Wolfgang Schüssel in early 2000 by the other 14 Member States' governments. These arrangements came into effect on 1 February 2003 under the provisions of the Treaty of Nice.

Geographic criteria

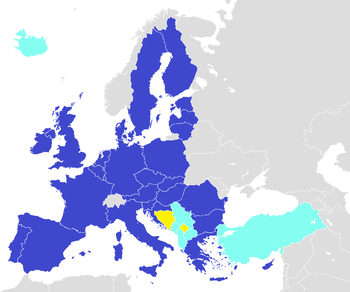

Article 49 (formerly Article O) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU)[3] or Maastricht Treaty states that any European country that respects the principles of the EU may apply to join. Countries' classification as European is "subject to political assessment"[4] by the Commission and more importantly—the European Council.

Although non-European states are not considered eligible to be members, they may enjoy varying degrees of integration with the EU, set out by international agreements. The general capacity of the community and the member states to conclude association agreements with third countries is being developed. Moreover, specific frameworks for integration with third countries are emerging—including most prominently the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP). This notably replaces the Barcelona process which previously provided the framework for the EU's relations with its Mediterranean neighbours in North Africa and West Asia.

The ENP should not be confused with the Stabilisation and Association Process in the Western Balkans or the European Economic Area. Russia does not fall within the scope of the ENP, but is subject to a separate framework. The European Neighbourhood Policy can be interpreted as the drawing up of the Union's borders for the foreseeable future. Another way the EU is integrating with neighbouring countries is through the Mediterranean Union, made up of EU countries and others bordering the Mediterranean sea.

Political criteria

Democracy

Functional democratic governance requires that all citizens of the country should be able to participate, on an equal basis, in the political decision making at every single governing level, from local municipalities up to the highest, national, level. This also requires free elections with a secret ballot, the right to establish political parties without any hindrance from the state, fair and equal access to a free press, free trade union organisations, freedom of personal opinion, and executive powers restricted by laws and allowing free access to judges independent of the executive.

Rule of law

The rule of law implies that government authority may only be exercised in accordance with documented laws, which were adopted through an established procedure. The principle is intended to be a safeguard against arbitrary rulings in individual cases.

Human rights

Human rights are those rights which every person holds because of their quality as a human being; human rights are "inalienable" and belonging to all humans. If a right is inalienable, that means it cannot be bestowed, granted, limited, bartered away, or sold away (e.g. one cannot sell oneself into slavery). These include the right to life, the right to be prosecuted only according to the laws that are in existence at the time of the offence, the right to be free from slavery, and the right to be free from torture.

The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights is considered the most authoritative formulation of human rights, although it lacks the more effective enforcement mechanism of the European Convention on Human Rights. The requirement to fall in line with this formulation forced several nations that recently joined the EU to implement major changes in their legislation, public services and judiciary. Many of the changes involved the treatment of ethnic and religious minorities, or removal of disparities of treatment between different political factions.

Respect for and protection of minorities

Members of such national minorities should be able to maintain their distinctive culture and practices, including their language (as far as not contrary to the human rights of other people, nor to democratic procedures and rule of law), without suffering any discrimination. A Council of Europe convention, the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (treaty No. 157) reflected this principle. But the Convention did not include a clear definition of what constituted a national minority. As a result, some signatory states added official declarations on the matter:[5]

- Austria: "The Republic of Austria declares that, for itself, the term 'national minorities' within the meaning of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities is understood to designate those groups which come within the scope of application of the Law on Ethnic Groups (Volksgruppengesetz, Federal Law Gazette No. 396/1976) and which live and traditionally have had their home in parts of the territory of the Republic of Austria and which are composed of Austrian citizens with non-German mother tongues and with their own ethnic cultures."

- Azerbaijan: "The Republic of Azerbaijan, confirming its adherence to the universal values and respecting human rights and fundamental freedoms, declares that the ratification of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities and implementation of its provisions do not imply any right to engage in any activity violating the territorial integrity and sovereignty, or internal and international security of the Republic of Azerbaijan."

- Belgium: "The Kingdom of Belgium declares that the Framework Convention applies without prejudice to the constitutional provisions, guarantees or principles, and without prejudice to the legislative rules which currently govern the use of languages. The Kingdom of Belgium declares that the notion of national minority will be defined by the inter-ministerial conference of foreign policy."

- Bulgaria: "Confirming its adherence to the values of the Council of Europe and the desire for the integration of Bulgaria into the European structures, committed to the policy of protection of human rights and tolerance to persons belonging to minorities, and their full integration into Bulgarian society, the National Assembly of the Republic of Bulgaria declares that the ratification and implementation of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities do not imply any right to engage in any activity violating the territorial integrity and sovereignty of the unitary Bulgarian State, its internal and international security."

- Denmark: "In connection with the deposit of the instrument of ratification by Denmark of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, it is hereby declared that the Framework Convention shall apply to the German minority in South Jutland of the Kingdom of Denmark."

- Estonia: "The Republic of Estonia understands the term national minorities, which is not defined in the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, as follows: are considered as national minority those citizens of Estonia who - reside on the territory of Estonia; - maintain longstanding, firm and lasting ties with Estonia; - are distinct from Estonians on the basis of their ethnic, cultural, religious or linguistic characteristics; - are motivated by a concern to preserve together their cultural traditions, their religion or their language, which constitute the basis of their common identity."

- Germany: "The Framework Convention contains no definition of the notion of national minorities. It is therefore up to the individual Contracting Parties to determine the groups to which it shall apply after ratification. National Minorities in the Federal Republic of Germany are the Danes of German citizenship and the members of the Sorbian people with German citizenship. The Framework Convention will also be applied to members of the ethnic groups traditionally resident in Germany, the Frisians of German citizenship and the Sinti and Roma of German citizenship."

- Latvia: "The Republic of Latvia – Recognizing the diversity of cultures, religions and languages in Europe, which constitutes one of the features of the common European identity and a particular value, – Taking into account the experience of the Council of Europe member States and the wish to foster the preservation and development of national minority cultures and languages, while respecting the sovereignty and national-cultural identity of every State, – Affirming the positive role of an integrated society, including the command of the State language, to the life of a democratic State, – Taking into account the specific historical experience and traditions of Latvia, declares that the notion 'national minorities' which has not been defined in the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, shall, in the meaning of the Framework Convention, apply to citizens of Latvia who differ from Latvians in terms of their culture, religion or language, who have traditionally lived in Latvia for generations and consider themselves to belong to the State and society of Latvia, who wish to preserve and develop their culture, religion or language. Persons who are not citizens of Latvia or another State but who permanently and legally reside in the Republic of Latvia, who do not belong to a national minority within the meaning of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities as defined in this declaration, but who identify themselves with a national minority that meets the definition contained in this declaration, shall enjoy the rights prescribed in the Framework Convention, unless specific exceptions are prescribed by law. The Republic of Latvia declares that it will apply the provisions of Article 10, paragraph 2, of the Framework Convention without prejudice to the Satversme (Constitution) of the Republic of Latvia and the legislative acts governing the use of the State language that are currently into force. The Republic of Latvia declares that it will apply the provisions of Article 11, paragraph 3, of the Framework Convention without prejudice to the Satversme (Constitution) of the Republic of Latvia and the legislative acts governing the use of the State language that are currently into force."

- Liechtenstein: "The Principality of Liechtenstein declares that Articles 24 and 25, in particular, of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities of 1 February 1995 are to be understood having regard to the fact that no national minorities in the sense of the Framework Convention exist in the territory of the Principality of Liechtenstein. The Principality of Liechtenstein considers its ratification of the Framework Convention as an act of solidarity in the view of the objectives of the Convention."

- Luxembourg: "The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg understands by 'national minority' in the meaning of the Framework Convention, a group of people settled for numerous generations on its territory, having the Luxembourg nationality and having kept distinctive characteristics in an ethnic and linguistic way. On the basis of this definition, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg is induced to establish that there is no "national minority" on its territory."

- Malta: "The Government of Malta reserves the right not to be bound by the provisions of Article 15 insofar as these entail the right to vote or to stand for election either for the House of Representatives or for Local Councils. The Government of Malta declares that Articles 24 and 25, in particular, of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities of 1 February 1995 are to be understood having regard to the fact that no national minorities in the sense of the Framework Convention exist in the territory of the Government of Malta. The Government of Malta considers its ratification of the Framework Convention as an act of solidarity in the view of the objectives of the Convention."

- Netherlands: "The Kingdom of the Netherlands will apply the Framework Convention to the Frisians. The Government of the Netherlands assumes that the protection afforded by Article 10, paragraph 3, does not differ, despite the variations in wording, from that afforded by Article 5, paragraph 2, and Article 6, paragraph 3 (a) and (e), of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. The Kingdom of the Netherlands accepts the Framework Convention for the Kingdom in Europe."

- Poland: "Taking into consideration the fact, that the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities contains no definition of the national minorities notion, the Republic of Poland declares, that it understands this term as national minorities residing within the territory of the Republic of Poland at the same time whose members are Polish citizens. The Republic of Poland shall also implement the Framework Convention under Article 18 of the Convention by conclusion of international agreements mentioned in this Article, the aim of which is to protect national minorities in Poland and minorities or groups of Poles in other States."

- Russia: "The Russian Federation considers that none is entitled to include unilaterally in reservations or declarations, made while signing or ratifying the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, a definition of the term 'national minority', which is not contained in the Framework Convention.

- Slovenia: "Considering that the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities does not contain a definition of the notion of national minorities and it is therefore up to the individual Contracting Party to determine the groups which it shall consider as national minorities, the Government of the Republic of Slovenia, in accordance with the Constitution and internal legislation of the Republic of Slovenia, declares that these are the autochthonous Italian and Hungarian National Minorities. In accordance with the Constitution and internal legislation of the Republic of Slovenia, the provisions of the Framework Convention shall apply also to the members of the Roma community, who live in the Republic of Slovenia."

- Sweden: "The national minorities in Sweden are Sami, Swedish Finns, Tornedalers, Roma and Jews."

- Switzerland: "Switzerland declares that in Switzerland national minorities in the sense of the framework Convention are groups of individuals numerically inferior to the rest of the population of the country or of a canton, whose members are Swiss nationals, have long-standing, firm and lasting ties with Switzerland and are guided by the will to safeguard together what constitutes their common identity, in particular their culture, their traditions, their religion or their language. Switzerland declares that the provisions of the framework Convention governing the use of the language in relations between individuals and administrative authorities are applicable without prejudice to the principles observed by the Confederation and the cantons in the determination of official languages."

- Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia: "Referring to the Framework Convention, and taking into account the latest amendments to the Constitution of the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia submits the revised declaration to replace the previous two declarations on the aforesaid Convention: The term 'national minorities' used in the Framework Convention and the provisions of the same Convention shall be applied to the citizens of the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia who live within its borders and who are part of the Albanian people, Turkish people, Vlach people, Serbian people, Roma people and Bosniac people."

A consensus was reached (among other legal experts, the so-called groups of Venice) that this convention refers to any ethnic, linguistic or religious people that defines itself as a distinctive group, that forms the historic population or a significant historic and current minority in a well-defined area, and that maintains stable and friendly relations with the state in which it lives. Some experts and countries wanted to go further. Nevertheless, recent minorities, such as immigrant populations, have nowhere been listed by signatory countries as minorities concerned by this convention.

After the entrance of Romania and Bulgaria, there has been criticism on the fact that they have been admitted even if they do not give enough welfare to their Romani minorities to be able to sustain, which made this minority travel to richer EU countries to beg.

Economic criteria

The economic criteria, broadly speaking, require that candidate countries have a functioning market economy and that their producers have the capability to cope with competitive pressure and market forces within the Union. The Euro convergence criteria and European Exchange Rate Mechanism has been used to prepare countries for joining the Eurozone, both founding and later members.

Legislative alignment

Finally, and technically outside the Copenhagen criteria, comes the further requirement that all prospective members must enact legislation to bring their laws into line with the body of European law built up over the history of the Union, known as the acquis communautaire. In preparing for each admission, the acquis is divided into separate chapters, each dealing with different policy areas. For the process of the fifth enlargement that concluded with the admission of Bulgaria and Romania in 2007, there were 31 chapters. For the talks with Croatia, Turkey and Iceland the acquis has been split further into 35 chapters.

References

- 1 2 "European Commission—Enlargement—Potential Candidates". Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ↑ Presidency Conclusions, Copenhagen European Council 1993, 7.A.iii http://www.europarl.europa.eu/enlargement/ec/pdf/cop_en.pdf

- ↑ The head of states of the EU member states (7 February 1992). "The Maastricht Treaty" (PDF). Treaty on the European Union. eurotreaties.com. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ Members of the European Parliament (19 May 1998). "Legal questions of enlargement". Enlargement of the European Union. The European Parliament. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑