Presidency of Calvin Coolidge

The presidency of Calvin Coolidge began on August 2, 1923, when Calvin Coolidge became President of the United States upon the sudden death of Warren G. Harding, and ended on March 4, 1929. A member of the Republican Party, Coolidge had been Vice President of the United States for 2 years, 151 days when he succeeded to the presidency. Elected to a full four–year term in 1924, he gained a reputation as a small-government conservative.

Coolidge, the 30th United States president, restored public confidence in the presidency after the scandals of his predecessor's administration, and left office with considerable popularity.[1] He supported policies of high tariffs, tax reduction, and federal support to industry during a period of sustained economic prosperity for the nation. He resisted efforts to involve the federal government in the persistent farm crisis that affected many rural communities. In foreign policy, Coolidge continued to keep the United States out of the League of Nations, but he engaged with foreign leaders and sponsored the Kellogg–Briand Pact of 1928.

While Coolidge was greatly admired during his time in office, public opinion soured as the nation plunged into the Great Depression after he left office. Many linked the nation's economic collapse to Coolidge's policy decisions, which did nothing to discourage the wild speculation that was going on and rendered so many vulnerable to economic ruin. Though his reputation underwent a renaissance during the Ronald Reagan administration, modern assessments of Coolidge's presidency are divided. He is adulated among advocates of smaller government and laissez-faire; supporters of an active central government generally view him less favorably, while both sides praise his stalwart support of racial equality.[2] Coolidge was succeeded by fellow Republican Herbert Hoover, who served as Secretary of Commerce throughout both the Coolidge and Harding administrations.

Accession

On August 2, 1923, President Harding died unexpectedly in San Francisco while on a speaking tour of the western United States. Vice President Coolidge was in Vermont visiting his family home, which had neither electricity nor a telephone, when he received word by messenger of Harding's death.[3] He dressed, said a prayer, and came downstairs to greet the reporters who had assembled.[3] His father, a notary public, administered the oath of office in the family's parlor by the light of a kerosene lamp at 2:47 a.m. on August 3, 1923; President Coolidge then went back to bed. He returned to Washington the next day, and was sworn in again by Justice Adolph A. Hoehling Jr. of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, to forestall any questions about the authority of a notary public to administer the presidential oath.[4]

The nation initially did not know what to make of Coolidge, who had maintained a low profile in the Harding administration; many had even expected him to be replaced on the ballot in 1924.[5] The 1923 United Mine Workers coal strike presented an immediate challenge to Coolidge, who avoided attempting to personally end the strike but convened the United States Coal Commission under the advice of Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover. Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot, a progressive Republican and potential rival for the 1924 presidential nomination, quickly settled the strike with little input from the federal government. Pinchot's settlement of the strike backfired, as he took the blame for rising coal prices, and Coolidge quickly consolidated his power among Republican elites.[6]

Coolidge addressed Congress when it reconvened on December 6, 1923, giving a speech that supported many of Harding's policies, including Harding's formal budgeting process and the enforcement of immigration restrictions.[7] Coolidge's speech was the first presidential speech to be broadcast over the radio.[8] The Washington Naval Treaty was proclaimed just one month into Coolidge's term, and was generally well received in the country.[9]

Administration

Cabinet

| The Coolidge Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Calvin Coolidge | 1923–1929 |

| Vice President | none | 1923–1925 |

| Charles G. Dawes | 1925–1929 | |

| Secretary of State | Charles Evans Hughes | 1923–1925 |

| Frank B. Kellogg | 1925–1929 | |

| Secretary of Treasury | Andrew Mellon | 1923–1929 |

| Secretary of War | John W. Weeks | 1923–1925 |

| Dwight F. Davis | 1925–1929 | |

| Attorney General | Harry M. Daugherty | 1923–1924 |

| Harlan F. Stone | 1924–1925 | |

| John G. Sargent | 1925–1929 | |

| Postmaster General | Harry S. New | 1923–1929 |

| Secretary of the Navy | Edwin Denby | 1923–1924 |

| Curtis D. Wilbur | 1924–1929 | |

| Secretary of the Interior | Hubert Work | 1923–1928 |

| Roy O. West | 1928–1929 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Henry C. Wallace | 1923–1924 |

| Howard M. Gore | 1924–1925 | |

| William M. Jardine | 1925–1929 | |

| Secretary of Commerce | Herbert Hoover | 1923–1928 |

| William F. Whiting | 1928–1929 | |

| Secretary of Labor | James J. Davis | 1923–1929 |

Although a few of Harding's cabinet appointees were scandal-tarred, Coolidge initially retained all of them, out of an ardent conviction that as successor to a deceased elected president he was obligated to retain Harding's counselors and policies until the next election. He kept Harding's able speechwriter Judson T. Welliver; Stuart Crawford replaced Welliver in November 1925.[10] Coolidge appointed C. Bascom Slemp, a Virginia Congressman and experienced federal politician, to work jointly with Edward T. Clark, a Massachusetts Republican organizer whom he retained from his vice-presidential staff, as Secretaries to the President (a position equivalent to the modern White House Chief of Staff).[9] Perhaps the most powerful person in Coolidge's Cabinet was Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon, who controlled the administration's financial policies and was regarded by many, including House Minority Leader John Nance Garner, as more powerful than Coolidge himself.[11] Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover also held a prominent place in Coolidge's Cabinet, in part because Coolidge found value in Hoover's ability to win positive publicity with his pro-business proposals.[12] Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes directed Coolidge's foreign policy until he resigned in 1925 following Coolidge's re-election. He was replaced by Frank B. Kellogg, who had previously served as a Senator and as the ambassador to Great Britain. Coolidge made two other appointments following his re-election, with William M. Jardine taking the position of Secretary of Agriculture and John G. Sargent becoming Attorney General.[13] Coolidge did not have a vice president during his first term, but Charles Dawes became vice president during Coolidge's second term, and Dawes and Coolidge clashed over farm policy and other issues.[14]

Judicial appointments

Coolidge appointed one justice to the Supreme Court of the United States, Harlan Fiske Stone in 1925. Stone was Coolidge's fellow Amherst alumnus, a Wall Street lawyer and conservative Republican. Stone was serving as dean of Columbia Law School when Coolidge appointed him to be attorney general in 1924 to restore the reputation tarnished by Harding's Attorney General, Harry M. Daugherty.[15] Stone proved to be a firm believer in judicial restraint and was regarded as one of the court's three liberal justices who would often vote to uphold New Deal legislation.[16] President Franklin D. Roosevelt later appointed Stone to be chief justice, a position Stone held until his death in 1946.[17]

Coolidge nominated 17 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 61 judges to the United States district courts. He appointed judges to various specialty courts as well, including Genevieve R. Cline, who became the first woman named to the federal judiciary when Coolidge placed her on the United States Customs Court in 1928.[18] Coolidge also signed the Judiciary Act of 1925 into law, allowing the Supreme Court more discretion over its workload.

Harding administration scandals

In the waning days of Harding's administration, several scandals had begun to emerge into public view. Though Coolidge was not implicated in any corrupt dealings, he dealt with the fallout of the scandals in the early days of his presidency. The Teapot Dome Scandal tainted the careers of former Secretary of the Interior Albert B. Fall (who had resigned in March 1923) and Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby, and additional scandals implicated Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty and Charles R. Forbes, the former Director of the Veterans Bureau. A bipartisan Senate investigation led by Thomas J. Walsh and Robert LaFolette began just weeks into Coolidge's presidency. As the investigation uncovered further misconduct, Coolidge appointed Atlee Pomerene and Owen Roberts as special prosecutors, but he remained personally unconvinced as to the guilt of Harding's appointees. Despite congressional pressure, he refused to dismiss Denby, who instead resigned of his own accord in March 1924. That same month, after Daugherty refused to resign, Coolidge fired him. Coolidge also replaced the Director of the Bureau of Investigation, William J. Burns, with J. Edgar Hoover. The investigation by Pomerene and Roberts, combined with the departure of the scandal-tarred Harding appointees, served to disassociate Coolidge from the Harding administration's misdeeds.[19]

Economy and regulation

| it is probable that a press which maintains an intimate touch with the business currents of the nation is likely to be more reliable than it would be if it were a stranger to these influences. After all, the chief business of the American people is business. They are profoundly concerned with buying, selling, investing and prospering in the world. (emphasis added) |

| President Calvin Coolidge's address to the American Society of Newspaper Editors, Washington D.C., January 25, 1925.[20] |

During Coolidge's presidency, the United States experienced a period of rapid economic growth known as the "Roaring Twenties." The number of automobiles in the United States increased from 7 million in 1919 to 23 million in 1929, while the percentage of households with electricity rose from 16 percent in 1912 to 60 percent in the mid-1920s.[21] The regulatory state under Coolidge was, as one biographer described it, "thin to the point of invisibility."[22] Coolidge demonstrated his disdain for regulation by appointing commissioners to the Federal Trade Commission and the Interstate Commerce Commission who did little to restrict the activities of businesses under their jurisdiction.[23] He also avoided interfering with the workings of the Federal Reserve, which kept interest rates low and allowed for the expansion of margin trading in the stock market.[24]

Coolidge believed that promoting the interests of manufacturers was good for society as a whole, and he sought to reduce taxes and regulations on businesses while imposing tariffs to protect those interests against foreign competition.[25] The 1922 Fordney–McCumber Tariff allowed the president some leeway in determining tariff rates, and Coolidge used his power to raise the already-high rates set by Fordney–McCumber.[26]

Coolidge left the administration's industrial policy in the hands of Secretary of Commerce Hoover, who energetically used government auspices to promote business efficiency and develop airlines and radio.[27] The Radio Act of 1927 established the Federal Radio Commission under the auspices of the Commerce Department, and the commission granted numerous licenses to large, commercial radio stations.[28] Hoover was a strong proponent of cooperation between government and business, and he organized numerous conferences of intellectuals and businessmen which made various recommendations. Relatively few reforms were passed, but the proposals created the image of an active administration.[29]

Some have labeled Coolidge as an adherent of the laissez-faire ideology, which some critics claim led to the Great Depression.[30] Historian Robert Sobel argues instead that Coolidge's belief in federalism guided his economic policy, writing, "as Governor of Massachusetts, Coolidge supported wages and hours legislation, opposed child labor, imposed economic controls during World War I, favored safety measures in factories, and even worker representation on corporate boards...such matters were considered the responsibilities of state and local governments."[31][32] Historian David Greenberg argues that Coolidge's economic policies, designed primarily to bolster American industry, are best described as Hamiltonian rather than laissez-faire.[25]

Taxation and government spending

Coolidge took office in the aftermath of World War I, during which the United States had raised taxes to unprecedented rates.[33] Coolidge's taxation policy was that of Treasury Secretary Mellon, the ideal that "scientific taxation"—lower taxes—actually increase rather than decrease government receipts.[34] Mellon believed that the benefits of lower taxes on the rich would "trickle down" to the benefit of society as whole by encouraging increased investment. The Revenue Act of 1921, which had been proposed by Mellon, had reduced the top marginal tax rate from 71% to 58%, and Mellon sought to further reduce rates and abolish other taxes during Coolidge's presidency.[35]

Though Coolidge sought to lower spending, he spent early 1924 opposing the World War Adjusted Compensation Act or "Bonus Bill."[36] With a budget surplus, many legislators wanted to reward the veterans of World War I with extra compensation, arguing that the soldiers had been paid poorly during the war. Coolidge and Mellon preferred to use the budget surplus to cut taxes, and they did not believe that the country could pass both bills and maintain a balanced budget. However, the bill gained wide support and was endorsed by several prominent Republicans, including Henry Cabot Lodge and Charles Curtis. Coolidge vetoed the Bonus Bill, but Congress overrode his veto, handing Coolidge a defeat in his first major legislative battle.[37]

With his legislative priorities now in jeopardy, Coolidge backed off on his goal of lowering the top tax rate down to 25%.[38] After much legislative haggling, Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1924, which reduced income tax rates and eliminated all income taxation for some two million people.[39] The act reduced the top marginal tax rate from 58% to 46%, but increased the estate tax and bolstered it with a new gift tax.[40] After his re-election in 1924, Coolidge sought further tax reductions,[41] and Congress cut taxes with the Revenue Acts of 1926 and 1928, all the while continuing to keep spending down so as to reduce the overall federal debt.[42] By 1927, only the wealthiest 2% of taxpayers paid any federal income tax.[42] Federal spending remained flat during Coolidge's administration, allowing one-fourth of the federal debt to be retired in total. Coolidge would be the last president to significantly reduce federal debt until Bill Clinton's tenure in the 1990s, although intervening presidents presided over a reduction of debt in proportion to the country's gross domestic product.[43] During Coolidge's presidency, state and local governments saw considerable growth, surpassing the federal budget in 1927.[44]

Opposition to farm subsidies

Perhaps the most contentious issue of Coolidge's presidency was relief for farmers. During the 1920s, the United States faced a farm crisis that proved devastating to many rural areas.[45] Some in Congress proposed a bill designed to fight falling agricultural prices by allowing the federal government to purchase crops to sell abroad at lower prices.[46] Agriculture Secretary Henry C. Wallace and other administration officials favored the bill when it was introduced in 1924, but rising prices convinced many in Congress that the bill was unnecessary, and it was defeated just before the elections that year.[47] Wallace died in 1924, and was replaced by William Marion Jardine, an outspoken opponent of the McNary–Haugen Farm Relief Bill and government interventionism in agriculture.[48] McNary-Haugen proposed a federal farm board that would purchase surplus production in high-yield years and hold it (when feasible) for later sale or sell it abroad.[49] Coolidge opposed McNary-Haugen, declaring that agriculture must stand "on an independent business basis," and said that "government control cannot be divorced from political control."[49] Instead of manipulating prices, he favored instead Herbert Hoover's proposal to create profits by modernizing agriculture. Secretary Mellon wrote a letter denouncing the McNary-Haugen measure as unsound and likely to cause inflation, and it was defeated.[50]

After McNary-Haugen's defeat, Coolidge supported a less radical measure, the Curtis-Crisp Act, which would have created a federal board to lend money to farm co-operatives in times of surplus; the bill did not pass.[50] In February 1927, Congress took up the McNary-Haugen bill again, this time narrowly passing it, and Coolidge vetoed it.[51] The bill, which bore the name of Republicans members of Congress, had passed the Senate with the help of Coolidge's own vice president.[14] In his veto message, Coolidge expressed the belief that the bill would do nothing to help farmers, benefiting only exporters and expanding the federal bureaucracy.[52] Congress did not override the veto, but it passed the bill again in May 1928 by an increased majority; again, Coolidge vetoed it.[51] "Farmers never have made much money," said Coolidge, the Vermont farmer's son. "I do not believe we can do much about it."[53] Secretary Jardine developed his own plan to address the farm crisis that established a Federal Farm Board, and his plan eventually would form the basis of the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1929.[54]

Flood control

Coolidge has often been criticized for his actions during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the worst natural disaster to hit the Gulf Coast until Hurricane Katrina in 2005.[55] Although he did eventually name Secretary Hoover to a commission in charge of flood relief, scholars argue that Coolidge overall showed a lack of interest in federal flood control.[55] Coolidge did not believe that personally visiting the region after the floods would accomplish anything, and that it would be seen as mere political grandstanding. He also did not want to incur the federal spending that flood control would require; he believed property owners should bear much of the cost.[56] On the other hand, Congress wanted a bill that would place the federal government completely in charge of flood mitigation.[57] When Congress passed a compromise measure in 1928, Coolidge declined to take credit for it and signed the Flood Control Act of 1928 in private on May 15.[58]

Civil rights

Coolidge spoke in favor of the civil rights of African-Americans, saying in his first State of the Union address that their rights were "just as sacred as those of any other citizen" under the U.S. Constitution and that it was a "public and a private duty to protect those rights."[59][60] He appointed no known members of the Ku Klux Klan to office; indeed, the Klan lost most of its influence during his term.[61] His administration commissioned studies to improve programs for Native Americans.

Coolidge repeatedly called for laws to prohibit lynching, saying in his 1923 State of the Union address that it was a "hideous crime" of which African-Americans were "by no means the sole sufferers" but made up the "majority of the victims."[60] However, most Congressional attempts to pass this legislation were filibustered by Southern Democrats.[62] Coolidge appointed some African-Americans to federal office; he retained Harding's choice of Walter L. Cohen of New Orleans, Louisiana, as the comptroller of customs and offered Cohen the post of minister to Liberia, which the businessman declined.

On June 2, 1924, Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act, which granted U.S. citizenship to all American Indians, while permitting them to retain tribal land and cultural rights. By that time, two-thirds of the people were already citizens, having gained it through marriage, military service (veterans of World War I were granted citizenship in 1919), or the land allotments that had earlier taken place.[63][64][65] The act was unclear on whether the federal government or the tribal leaders retained tribal sovereignty.[66] His administration appointed the Committee of One Hundred, a reform panel to examine federal institutions and programs dealing with Indian nations. This committee recommended that the government conduct an in-depth investigation into reservation life (health, education, economics, justice, civil rights, etc.). This was commissioned through the Department of Interior and conducted by the Brookings Institution, resulting in the groundbreaking Meriam Report of 1928.

Immigration

In reaction to immigration from Eastern Europe and other regions, a strong nativism movement had arisen in the years prior to Coolidge's presidency. Prior to Coolidge's presidency, Congress had passed the Immigration Act of 1917, which imposed a literacy test on immigrants, as well as the Emergency Quota Act of 1921. The latter act had put a temporary cap on the number of immigrants accepted into the country. Coolidge endorsed an extension of the cap on immigration in his 1923 State of the Union, but his administration was less supportive of the continuation of the National Origins Formula, which effectively restricted immigration from countries outside of Northwestern Europe. Secretary of State Hughes strongly opposed the quotas, particularly the total ban on Japanese immigration, which violated the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907 with Japan. However, when Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, Coolidge signed the bill despite his reservations. As the Immigration Act of 1924 remained in force until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, it greatly affected the demographics of immigration for several decades.[67]

Foreign policy

Although not an isolationist, Coolidge was reluctant to enter into foreign alliances.[68] He considered the 1920 Republican victory as a rejection of the Wilsonian position that the United States should join the League of Nations.[69] While not completely opposed to the idea, Coolidge believed the League, as then constituted, did not serve American interests, and he did not advocate membership.[69] He spoke in favor of the United States joining the Permanent Court of International Justice (World Court), provided that the nation would not be bound by advisory decisions.[70] In 1926, the Senate eventually approved joining the Court (with reservations).[71] The League of Nations accepted the reservations, but it suggested some modifications of its own.[72] As the Senate failed to act, the United States never joined the World Court.[72]

In the aftermath of World War I, several European nations struggled with debt, including billions of dollars owed to the United States. These European nations were owed an enormous sum from Germany in the form of World War I reparations, and the German economy buckled under the weight of these reparations. Coolidge rejected calls to forgive Europe's debt or lower tariffs on European goods, but the Occupation of the Ruhr in 1923 stirred him to action. On Secretary of State Hughes's initiative, Coolidge appointed Charles Dawes to lead an international commission to reach an agreement on Germany's reparations. The resulting Dawes Plan provided for a withdrawal restructuring of the German debt, and the United States loaned money to Germany to help it repay its debt other countries. The Dawes Plan led to a boom in the German economy and a sentiment of international cooperation. In 1925, Germany and several other European states signed the Locarno Treaties, which settled several territorial disputes.[73]

Coolidge's primary foreign policy initiative was the Kellogg–Briand Pact of 1928, named for Secretary of State Kellogg and French foreign minister Aristide Briand. The treaty, ratified in 1929, committed signatories—the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan—to "renounce war, as an instrument of national policy in their relations with one another."[74] The treaty did not achieve its intended result—the outlawry of war—but it did provide the founding principle for international law after World War II.[75] Coolidge's policy of international disarmament allowed the administration to decrease military spending, a part of Coolidge's broader policy of decreasing government spending.[76]

After the Mexican Revolution, the U.S. had refused to recognize the government of Álvaro Obregón, one of the revolution's leaders. Secretary of State Hughes had worked with Mexico to normalize relations during the Harding administration, and President Coolidge recognized the Mexican government in 1923. To help Obregón defeat a rebellion, Coolidge also lifted an embargo on Mexico and encouraged U.S. banks to loan to the Mexican government. In 1924, Plutarco Elías Calles took office as President of Mexico, and Calles sought to limit American property claims and take control of the holdings of the Catholic church. However, Ambassador Dwight Morrow convinced Calles to allow Americans to retain their rights to property purchased before 1917, and Mexico and the United States enjoyed good relations for the remainder of Coolidge's presidency.[77]

The United States' occupation of Nicaragua and Haiti continued under his administration, but Coolidge withdrew American troops from the Dominican Republic in 1924.[78] Coolidge led the U.S. delegation to the Sixth International Conference of American States, January 15–17, 1928, in Havana, Cuba. This was the only international trip Coolidge made during his presidency.[79] There, he extended an olive branch to Latin American leaders embittered over America's interventionist policies in Central America and the Caribbean.[80] For 88 years he was the only sitting president to have visited Cuba, until Barack Obama did so in 2016.[81]

Constitutional amendments

After the Supreme Court twice—in Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918) and Bailey v. Drexel Furniture (1922)—ruled that federal laws regulating and taxing goods produced by employees under the ages of 14 and 16 were unconstitutional, Congress, on June 2, 1924, approved an amendment to the United States Constitution that would that would specifically authorize Congress to regulate "labor of persons under eighteen years of age", and submitted it to the state legislatures for ratification.[82] Coolidge expressed support for the amendment in his first State of the Union.[83] The amendment, commonly known as the Child Labor Amendment, was never ratified by the requisite number of states, and, as there was no time limit set for its ratification, is still pending before the states.[84] However, the Supreme Court overturned Hammer v. Dagenhart in the 1941 case of United States v. Darby Lumber Co., making the Child Labor Amendment a moot issue.[85]

Elections

Election of 1924

The Republican Convention was held on June 10–12, 1924, in Cleveland, Ohio; Coolidge was nominated on the first ballot.[86] Coolidge's nomination made him the second unelected president to win his party's nomination for another term, after Theodore Roosevelt. Coolidge had been largely unknown when he took office, but he quickly shored up the support of most factions in his party, with the exception of the progressives.[87] The convention nominated Frank Lowden of Illinois for vice president on the second ballot, but he declined; former Brigadier General Charles G. Dawes was nominated on the third ballot and accepted.[86]

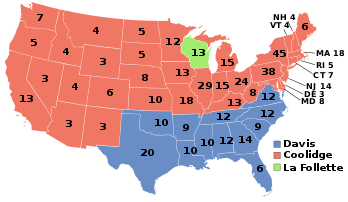

The Democrats held their convention the next month in New York City. The convention soon deadlocked, and after 103 ballots, the delegates finally agreed on a compromise candidate, John W. Davis, with Charles W. Bryan nominated for vice president. The Democrats' hopes were buoyed when Robert LaFolette, a Republican senator from Wisconsin, split from the GOP to form a new Progressive Party. La Follette's Progressives were motivated by the conservatism of both major party candidates, as well as an ongoing farm crisis that united many frustrated farmers.[88] They hoped to throw the election to the House by denying the Republican ticket an electoral vote majority, and some Progressives hoped to permanently disrupt the two-party system.[89] On the other hand, many believed that the split in the Republican party, like the one in 1912, would allow a Democrat to win the presidency.[90]

After the conventions and the death of his younger son Calvin, Coolidge became withdrawn; he later said that "when he [the son] died, the power and glory of the Presidency went with him."[91] It was the most subdued campaign since 1896, partly because of Coolidge's grief, but also because of his naturally non-confrontational style.[92] Coolidge relied on advertising executive Bruce Barton to lead his messaging campaign, and Barton's ads depicted Coolidge as a symbol of solidity in an era of speculation.[93] Although the Harding administration had been tarred by several scandals, by 1924 several Democrats had also been implicated and the partisan responsibility of the issue had been muddled.[94] Coolidge and Dawes won every state outside the South except Wisconsin, La Follette's home state. Coolidge won 54% of the popular vote, while Davis took just 28.8% and La Follette won 16.6%, one of the strongest third party presidential showings in U.S. history. In the concurrent Congressional elections, Republicans increased their majorities in the House and Senate.[95]

1926 midterm elections

Republicans lost seats in both the House and Senate in the 1926 midterm elections, but retained a majority in both houses. The reduced number of seats deprived Coolidge's conservative allies of a working majority in Congress.[96]

Election of 1928

While on vacation in the summer of 1927, Coolidge surprisingly issued a terse statement that he would not seek a second full term as president.[97] In his memoirs, Coolidge explained his decision not to run: "The Presidential office takes a heavy toll of those who occupy it and those who are dear to them. While we should not refuse to spend and be spent in the service of our country, it is hazardous to attempt what we feel is beyond our strength to accomplish."[98] Despite significant opposition from within the party, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover won the presidential nomination at the 1928 Republican National Convention.[99] Coolidge was reluctant to endorse Hoover as his successor; on one occasion he remarked that "for six years that man has given me unsolicited advice—all of it bad."[100] Even so, Coolidge had no desire to split the party by publicly opposing the nomination of the popular commerce secretary.[101] Hoover won the 1928 presidential election in a third consecutive Republican landslide, taking 58.2% of the popular vote and 444 electoral votes over Democratic Governor Al Smith of New York. The 1928 Congressional elections also saw Republicans increase their majorities in the House and Senate.

References

- ↑ McCoy, pp. 420–21; Greenberg, pp. 49–53.

- ↑ Sobel, pp. 12–13; Greenberg, pp. 1–7.

- 1 2 Fuess, pp. 308–09.

- ↑ Fuess, pp. 310–15.

- ↑ Sobel, pp. 226–28; Fuess, pp. 303–05; Ferrell, pp. 43–51.

- ↑ Zieger, pp. 566-581.

- ↑ Fuess, pp. 328–29; Sobel, pp. 248–49.

- ↑ Shlaes, p. 271.

- 1 2 Fuess, pp. 320–22.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Rusnak, pp. 270-271.

- ↑ Polsky, pp. 224-27.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 111–112.

- 1 2 "Charles G. Dawes, 30th Vice President (1925-1929)". US Senate. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ↑ Fuess, p. 364.

- ↑ Galston, passim.

- ↑ Greenberg, p. 110.

- ↑ Freeman, p. 216.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 49–53.

- ↑ Shlaes, p. 324.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 68-69.

- ↑ Ferrell, p. 72.

- ↑ Ferrell, pp. 66–72; Sobel, p. 318.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 146–148.

- 1 2 Greenberg, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Ferrell, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 131–132.

- ↑ Polsky, pp. 226-27.

- ↑ Ferrell, p. 207.

- ↑ Sobel, Robert. "Coolidge and American Business". John F. Kennedy Library and Museum. Archived from the original on March 8, 2006.

- ↑ Greenberg, p. 47; Ferrell, p. 62.

- ↑ Keller, p. 780.

- ↑ Sobel, pp. 310–11; Greenberg, pp. 127–29.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 71-72.

- ↑ Fuess, p. 341.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 77–79.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Sobel, pp. 310–11; Fuess, pp. 382–83.

- ↑ Sobel, pp. 278–79.

- ↑ Greenberg, p. 128.

- 1 2 Ferrell, p. 170.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 3.

- ↑ Ferrell, p. 174.

- ↑ Williams, pp. 216-218.

- ↑ Ferrell, p. 84; McCoy, pp. 234–35.

- ↑ McCoy, p. 235.

- ↑ Williams, pp. 225-226.

- 1 2 Fuess, pp. 383–84.

- 1 2 Sobel, p. 327.

- 1 2 Fuess, p. 388; Ferrell, p. 93.

- ↑ Sobel, p. 331.

- ↑ Ferrell, p. 86.

- ↑ Williams, pp. 230-231.

- 1 2 Sobel, p. 315; Barry, pp. 286–87; Greenberg, pp. 132–35.

- ↑ McCoy, pp. 330–31.

- ↑ Barry, pp. 372–74.

- ↑ Greenberg, p. 135.

- ↑ Sobel, p. 250; McCoy, pp. 328–29.

- 1 2 Wikisource:Calvin Coolidge's First State of the Union Address

- ↑ Felzenberg, pp. 83–96.

- ↑ Sobel, pp. 249–50.

- ↑ Madsen, Deborah L., ed. (2015). The Routledge Companion to Native American Literature. Routledge. p. 168. ISBN 1317693191.

- ↑ Charles Kappler (1929). "Indian affairs: laws and treaties Vol. IV, Treaties". Government Printing Office. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

- ↑ Alysa Landry, "Calvin Coolidge: First Sitting Prez Adopted by Tribe Starts Desecration of Mount Rushmore", Indian Country Today, 26 July 2016; accessed same day

- ↑ Deloria, p. 91.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 82-84.

- ↑ Sobel, p. 342.

- 1 2 McCoy, pp. 184–85.

- ↑ McCoy, p. 360.

- ↑ McCoy, p. 363.

- 1 2 Greenberg, pp. 114–16.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 88–90.

- ↑ Fuess, pp. 421–23.

- ↑ McCoy, pp. 380–81; Greenberg, pp. 123–24.

- ↑ Keller, p. 778.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 117–119.

- ↑ Fuess, pp. 414–17; Ferrell, pp. 122–23.

- ↑ "Travels of President Calvin Coolidge". U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian.

- ↑ "Calvin Coolidge: Foreign Affairs". millercenter.org. Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ↑ Kim, Susanna (December 18, 2014). "Here's What Happened the Last Time a US President Visited Cuba". ABC News. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ↑ Huckabee, David C. (September 30, 1997). "Ratification of Amendments to the U.S. Constitution" (PDF). Congressional Research Service reports. Washington D.C.: Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress.

- ↑ Greenberg, p. 76.

- ↑ "Four amendments that almost made it into the constitution". Constitution Daily. Philadelphia: The National Constitution Center. March 23, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ↑ Vile, John R. (2003). Encyclopedia of Constitutional Amendments, Proposed Amendments, and Amending Issues, 1789-2002. ABC-CLIO. p. 63. ISBN 9781851094288.

- 1 2 Fuess, pp. 345–46.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 91–94.

- ↑ Shideler, pp. 448-449.

- ↑ Shideler, pp. 449-450.

- ↑ Sobel, p. 300.

- ↑ Coolidge 1929, p. 190.

- ↑ Sobel, pp. 302–03.

- ↑ Buckley, pp. 616–17.

- ↑ Bates, pp. 319-323.

- ↑ Greenberg, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Busch, Andrew (1999). Horses in Midstream. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 157.

- ↑ Sobel, p. 370.

- ↑ Coolidge 1929, p. 239.

- ↑ Rusnak, pp. 275-276.

- ↑ Ferrell, p. 195.

- ↑ McCoy, pp. 390–91; Wilson, pp. 122–23.

Further reading

Scholarly sources

- Barry, John M. (1997). Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-84002-4.

- Deloria, Vincent (1992). American Indian Policy in the Twentieth Century. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2424-7.

- Ferrell, Robert H. (1998). The Presidency of Calvin Coolidge. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0892-8.

- Freeman, Jo (2002). A Room at a Time: How Women Entered Party Politics. Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-9805-9.

- Fuess, Claude M. (1940). Calvin Coolidge: The Man from Vermont. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4067-5673-9.

- Greenberg, David (2006). Calvin Coolidge. The American Presidents Series. Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-6957-0.

- McCoy, Donald R. (1967). Calvin Coolidge: The Quiet President. Macmillan. ISBN 1468017772.

- Shlaes, Amity (2013). Coolidge. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-196755-9.

- Sobel, Robert (1998). Coolidge: An American Enigma. Regnery Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89526-410-7.

- White, William Allen (1938). A Puritan in Babylon: The Story of Calvin Coolidge. Macmillan.

- Wilson, Joan Hoff (1975). Herbert Hoover, Forgotten Progressive. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-94416-8.

Articles

- Bates, J. Leonard (January 1955). "The Teapot Dome Scandal and the Election of 1924". The American Historical Review. 60 (2): 303–322.

- Buckley, Kerry W. (December 2003). "'A President for the "Great Silent Majority': Bruce Barton's Construction of Calvin Coolidge". The New England Quarterly. 76 (4): 593–626. JSTOR 1559844. doi:10.2307/1559844.

- Felzenberg, Alvin S. (Fall 1998). "Calvin Coolidge and Race: His Record in Dealing with the Racial Tensions of the 1920s". New England Journal of History. 55 (1): 83–96.

- Galston, Miriam (November 1995). "Activism and Restraint: The Evolution of Harlan Fiske Stone's Judicial Philosophy". 70 Tul. L. Rev. 137.

- Keller, Robert R. (3 September 1982). "Supply-Side Economic Policies during the Coolidge-Mellon Era". Journal of Economic Issues. 16 (3): 773–790.

- Polsky, Andrew J.; Tkacheva, Olesya (Winter 2002). "Legacies versus Politics: Herbert Hoover, Partisan Conflict, and the Symbolic Appeal of Associationalism in the 1920s". International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society. 16 (2): 207–235.

- Rusnak, Robert J. (Spring 1983). "Andrew W. Mellon: Reluctant Kingmaker". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 13 (2): 269–278.

- Shideler, James H. (June 1950). "The La Follette Progressive Party Campaign of 1924". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. 33 (4): 444–457.

- Williams, C. Fred (Spring 1996). "William M. Jardine and the Foundations for Republican Farm Policy, 1925-1929". Agricultural History. 70 (2): 216–232.

- Zieger, Robert H. (December 1965). "Pinchot and Coolidge: The Politics of the 1923 Anthracite Crisis". The Journal of American History. 52 (3): 566–581.

Primary sources

- Coolidge, Calvin (1919). Have Faith in Massachusetts: A Collection of Speeches and Messages (2nd ed.). Houghton Mifflin.

- Coolidge, Calvin (2004) [1926]. Foundations of the Republic: Speeches and Addresses. University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 1-4102-1598-9.

- Coolidge, Calvin (1929). The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge. Cosmopolitan Book Corp. ISBN 0-944951-03-1.

- Coolidge, Calvin (2001). Peter Hannaford, ed. The Quotable Calvin Coolidge: Sensible Words for a New Century. Images From The Past, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-884592-33-1.

- Coolidge, Calvin (1964). Howard H. Quint and Robert H. Ferrell, ed. The Talkative President: The Off-the Record Press Conferences of Calvin Coolidge. University of Massachusetts Press.

External links

| Library resources about Presidency of Calvin Coolidge |

| By Presidency of Calvin Coolidge |

|---|

- Calvin Coolidge Presidential Library & Museum

- Calvin Coolidge Presidential Foundation

- Official White House biography

- Text of a number of Coolidge speeches, Miller Center of Public Affairs

- "Presidency of Calvin Coolidge collected news and commentary". The New York Times.

- Calvin Coolidge: A Resource Guide, Library of Congress

- Works by or about Presidency of Calvin Coolidge at Internet Archive

- President Coolidge, Taken on the White House Ground, the first presidential film with sound recording

- Presidency of Calvin Coolidge at DMOZ

- "Life Portrait of Calvin Coolidge", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, September 27, 1999

- Calvin Coolidge Personal Manuscripts

- Calvin Coolidge on IMDb

| U.S. Presidential Administrations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Harding |

Coolidge Presidency 1923–1929 |

Succeeded by Hoover |