Congress of the Confederation

| Congress of the Confederation | |

|---|---|

| United States of America | |

|

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

Term limits | 3 out of 6 years |

| History | |

| Established | March 1, 1781 |

| Disbanded | March 4, 1789 |

| Preceded by | Second Continental Congress |

| Succeeded by | 1st United States Congress |

| Leadership | |

Secretary | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | Variable; ~50 |

| Committees | Committee of the States |

| Committees | Committee of the Whole |

Length of term | 3-6 years |

| Authority | President of Congress |

| Salary | None |

| Elections | |

Last election | 1788 |

| Meeting place | |

| Variable, see below | |

| Constitution | |

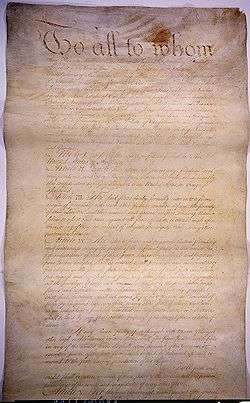

| Articles of Confederation | |

| Footnotes | |

| Though there were about 50 members of the Congress at a given time, it was the states that cast the votes, so there were effectively only 13 voting members or blocs. | |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| United States Continental Congress |

|---|

|

| Predecessors |

|

| 1st Continental Congress |

| 2nd Continental Congress |

| Congress of the Confederation |

| Members |

|

|

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States of America that existed from March 1, 1781, to March 4, 1789. A unicameral body with legislative and executive function, it comprised delegates appointed by the legislatures of the several states. Each state delegation had one vote. It was preceded by the Second Continental Congress (1775–1781) and governed under the newly adopted Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, which were proposed 1776–1777, adopted by the Continental Congress in July 1778 and finally agreed to by a unanimous vote of all thirteen states by 1781, held up by a long dispute over the cession of western territories beyond the Appalachian Mountains to the central government led by Maryland and a coalition of smaller states without western claims. The newly reorganized Congress at the time continued to refer itself as the Continental Congress throughout its eight-year history, although modern historians separate it from the earlier bodies, which operated under slightly different rules and procedures until the later part of American Revolutionary War.[1] The membership of the Second Continental Congress automatically carried over to the Congress of the Confederation when the latter was created by the ratification of the Articles of Confederation. It had the same secretary as the Second Continental Congress, namely Charles Thomson. The Congress of the Confederation was succeeded by the Congress of the United States as provided for in the Constitution of the United States, proposed September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia and ratified by the states through 1787 to 1788 and even into 1789 and 1790.[2]

Events

The Congress of the Confederation opened in the last stages of the American Revolution. Combat ended in October 1781, with the surrender of the British after the Siege and Battle of Yorktown. The British, however, continued to occupy New York City, while the American delegates in Paris, named by the Congress, negotiated the terms of peace with Great Britain.[3] Based on preliminary articles with the British negotiators made on November 30, 1782, and approved by the "Congress of the Confederation" on April 15, 1783, the Treaty of Paris was further signed on September 3, 1783, and ratified by Confederation Congress then sitting at the Maryland State House in Annapolis on January 14, 1784. This formally ended the American Revolutionary War between Great Britain and the thirteen former colonies, which on July 4, 1776, had declared independence. In December 1783, General George Washington, commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, journeyed to Annapolis after saying farewell to his officers (at Fraunces Tavern) and men who had just reoccupied New York City after the departing British Army. At the Maryland State House, where the Congress met in the Old Senate Chamber, he addressed the civilian leaders and delegates of Congress and returned to them the signed commission they had voted him back in June 1775, at the beginning of the conflict. With that simple gesture of acknowledging the first civilian power over the military, he took his leave and returned by horseback the next day to his home and family at Mount Vernon near the colonial river port city on the Potomac River at Alexandria in Virginia.

On March 1, 1781, the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union were signed by delegates of Maryland at a meeting of the Second Continental Congress, which then declared the Articles ratified. As historian Edmund Burnett wrote, "There was no new organization of any kind, not even the election of a new President." The Congress still called itself the Continental Congress. Nevertheless, despite its being generally the same exact governing body, with some changes in membership over the years as delegates came and went individually according to their own personal reasons and upon instructions of their state governments. Some modern historians would later refer to the Continental Congress after the ratification of the Articles as the Congress of the Confederation or the Confederation Congress. (The Congress itself continued to refer to itself at the time as the Continental Congress.)

The Congress had little power and without the external threat of a war against the British, it became more difficult to get enough delegates to meet to form a quorum. Nonetheless the Congress still managed to pass important laws, most notably the Northwest Ordinance of 1787.

The War of Independence saddled the country with an enormous debt. In 1784, the total Confederation debt was nearly $40 million. Of that sum, $8 million was owed to the French and Dutch. Of the domestic debt, government bonds, known as loan-office certificates, composed $11.5 million, certificates on interest indebtedness $3.1 million, and continental certificates $16.7 million.

The certificates were non-interest bearing notes issued for supplies purchased or impressed, and to pay soldiers and officers. To pay the interest and principal of the debt, Congress had twice proposed an amendment to the Articles granting them the power to lay a 5% duty on imports, but amendments to the Articles required the consent of all thirteen states. Rhode Island and Virginia rejected the 1781 impost plan while New York rejected the 1783 revised plan.

Without revenue, except for meager voluntary state requisitions, Congress could not even pay the interest on its outstanding debt. Meanwhile, the states regularly failed, or refused, to meet the requisitions requested of them by Congress.[4]

To that end, in September 1786, after resolving a series of disputes regarding their common border along the Potomac River, delegates of Maryland and Virginia called for a larger assembly to discuss various situations and governing problems to meet at the Maryland state capital on the Chesapeake Bay. The later Annapolis Convention with some additional state representatives joining in the sessions first attempted to look into improving the earlier original Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union. There were enough problems to bear further discussion and deliberation that the Convention called for a wider meeting to recommend changes and meet the next year in the late Spring of 1787 in Philadelphia. The Confederation Congress itself endorsed the Call and issued one on its own further inviting the states to send delegates. After meeting in secret all summer in the Old Pennsylvania State House now having acquired the nickname and new title of Independence Hall, from the famous action here eleven years earlier. The Philadelphia Convention, under the presidency of former General George Washington instead of a series of amendments, or altering the old charter, issued a proposed new Constitution for the United States to replace the 1776–1778 Articles. The Confederation Congress received and submitted the new Constitution document to the states, and the Constitution was later ratified by enough states (nine were required) to become operative in June 1788. On September 12, 1788, the Confederation Congress set the date for choosing the new Electors in the Electoral College that was set up for choosing a President as January 7, 1789, the date for the Electors to vote for the President as on February 4, 1789, and the date for the Constitution to become operative as March 4, 1789, when the new Congress of the United States should convene, and that they at a later date set the time and place for the Inauguration of the new first President of the United States.

The Congress of the Confederation continued to conduct business for another month after setting the various dates. On October 10, 1788, the Congress formed a quorum for the last time; afterwards, although delegates would occasionally appear, there were never enough to officially conduct business, and so the Congress of Confederation passed into history. The last meeting of the Continental Congress was held March 2, 1789, two days before the new Constitutional government took over; only one member was present at said meeting, Philip Pell, an ardent Anti-Federalist and opponent of the Constitution, who was accompanied by the Congressional secretary. Pell oversaw the meeting and adjourned the Congress sine die.

Meeting sites

Rather than having a fixed capital, the Congress of the Confederation met in numerous locations which may be considered United States capitals.[5] The Congress of the Confederation initially met at the Old Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall), in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (March 1, 1781 to June 21, 1783). – It then met at Nassau Hall, in Princeton, New Jersey (June 30, 1783 to November 4, 1783), – at the Maryland State House, in Annapolis, Maryland (November 26, 1783 to August 19, 1784), – at the French Arms Tavern, in Trenton, New Jersey (November 1, 1784 to December 24, 1784), – and the City Hall of New York (later known as Federal Hall), and in New York City, New York (January 11, 1785 to Autumn 1788).

Sessions

- First Confederation Congress

- March 1, 1781 – November 3, 1781, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Second Confederation Congress

- November 5, 1781 – November 2, 1782, Philadelphia

- Third Confederation Congress

- November 4, 1782 – June 21, 1783, Philadelphia

- June 30, 1783 – November 1, 1783, Princeton, New Jersey

- Fourth Confederation Congress

- November 3, 1783 – November 4, 1783, Princeton

- Fifth Confederation Congress

- November 26, 1783 – June 3, 1784, Annapolis, Maryland

- Sixth Confederation Congress

- November 1, 1784 – December 24, 1784, Trenton, New Jersey

- January 11, 1785 – November 4, 1785, New York, New York

- Seventh Confederation Congress

- November 7, 1785 – November 3, 1786, New York

- Eighth Confederation Congress

- November 6, 1786 – October 30, 1787, New York

- Ninth Confederation Congress

- November 5, 1787 – October 21, 1788, New York

- Tenth Confederation Congress

- November 3, 1788 – March 2, 1789, New York

See also

- America's Critical Period

- Committee of the States

- History of the United States (1776–1789)

- List of delegates to the Continental Congress

- President of the Continental Congress

References

- ↑ "Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789", Edited by Worthington C. Ford et al. 34 vols. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904–37.

- ↑ "Confederation Congress". Ohio Historical Society. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ↑ See: Peace of Paris (1783)#Treaty with the United States of America.

- ↑ Proposed Amendments to the Articles of Confederation Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789. Edited by Worthington C. Ford et al. 34 vols. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904–37. 31:494–98

- ↑ The Nine Capitals of the United States. United States Senate Historical Office. Accessed June 9, 2005. Based on Fortenbaugh, Robert, "The Nine Capitals of the United States", York, Pa.: Maple Press, 1948. See: List of capitals in the United States#Former national capitals.

Bibliography

- Burnett, Edmund C. "The Continental Congress". Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 0-8371-8386-3.

- Henderson, H. James. "Party Politics in the Continental Congress". Boston: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8191-6525-5.

- Jensen, Merrill (1950). "New Nation: A History of the United States During the Confederation, 1781–1789". New York: Knopf.

- McLaughlin, Andrew C. (1935). "A Constitutional History of the United States". ISBN 978-1-931313-31-5.

- Montross, Lynn. "The Reluctant Rebels; the Story of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789". New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 0-389-03973-X.

- Morris, Richard B. (1987). "The Forging of the Union, 1781–1789". New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-091424-6.

- Morris, Richard B. (1956). "The Confederation Period and the American Historian". William and Mary Quarterly. 13 (2): 139–156. JSTOR 1920529. doi:10.2307/1920529.

- Rakove, Jack N. (1979). "The Beginnings of National Politics: An Interpretive History of the Continental Congress". New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-394-42370-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Continental Congress. |

| Preceded by Second Continental Congress |

Legislature of the United States March 1, 1781 – March 4, 1789 |

Succeeded by United States Congress |