Sea serpent

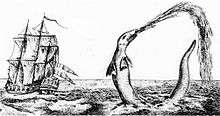

A sea serpent from Olaus Magnus's book History of the Northern Peoples (1555). | |

| Grouping | Legendary Creature |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Sea monster |

| Other name(s) | sea worm, worm, wyrm, cetus |

| Country | Various |

| Habitat | Sea |

A sea serpent, dragon or sea dragon is a dragon described in various mythologies (most notably Greek {Cetus, Echidna, Hydra, Scylla}, Mesopotamian {Tiamat}, Hebrew {Leviathan} and Norse {Jormungard}), in modern times some people believe that the creature is a cryptid.

Sightings of sea serpents have been reported for hundreds of years, and continue to be claimed today. Cryptozoologist Bruce Champagne identified more than 1,200 purported sea serpent sightings.[1] It is currently believed that the sightings can be best explained as known animals such as lungfish, oarfish, whales, or sharks (in particular, the frilled shark).[2] Some cryptozoologists have suggested that sea serpents are relict plesiosaurs, mosasaurs or other Mesozoic marine reptiles, an idea often associated with lake monsters such as the Loch Ness Monster.

In mythology

The "Drachenkampf" mytheme, the chief god in the role of the hero slaying a sea serpent, is widespread both in the Ancient Near East and in Indo-European mythology, e.g. Lotan and Hadad, Leviathan and Yahweh, Tiamat and Marduk (see also Labbu, Bašmu, Mušḫuššu), Illuyanka and Tarhunt, etc. The Hebrew Bible also has less mythological descriptions of large sea creatures as part of creation under God's command, such as the Tannin mentioned in Book of Genesis 1:21 and the "great serpent" of Amos 9:3. In the Aeneid, a pair of sea serpents killed Laocoön and his sons when Laocoön argued against bringing the Trojan Horse into Troy.

In antiquity and in the bible, dragons were imagined as huge serpentine monsters, which means that the image of a fire-breathing dragon with four/two legs and wings came much later—in the late Middle Ages; Most of stories say that they live in the sea, the Babylonian myths of Tiamat, the myth of the Hydra, Scylla, Cetus and Echidna in the Greek mythology and maybe even the Leviathan, confirm that.

In Norse mythology, Jörmungandr, or "Midgarðsormr" was a sea serpent so long that it encircled the entire world, Midgard. Some stories report of sailors mistaking its back for a chain of islands. Sea serpents also appear frequently in later Scandinavian folklore, particularly in that of Norway.[3][4]

In 1028 AD, Saint Olaf is said to have killed a sea serpent in Valldal, Norway, throwing its body onto the mountain Syltefjellet. Marks on the mountain are associated with the legend.[5][6] In Swedish ecclesiastic and writer Olaus Magnus's Carta marina, many marine monsters of varied form, including an immense sea serpent, appear. In his 1555 work History of the Northern Peoples, Magnus gives the following description of a Norwegian sea serpent:

Those who sail up along the coast of Norway to trade or to fish, all tell the remarkable story of how a serpent of fearsome size, 200 feet long and 20 feet wide, resides in rifts and caves outside Bergen. On bright summer nights this serpent leaves the caves to eat calves, lambs and pigs, or it fares out to the sea and feeds on sea nettles, crabs and similar marine animals. It has ell-long hair hanging from its neck, sharp black scales and flaming red eyes. It attacks vessels, grabs and swallows people, as it lifts itself up like a column from the water.[7][8]

Notable cases

An apparent eye-witness account is found in Aristotle's Historia Animalium. Strabo makes reference to an eye witness account of a dead sea creature sighted by Poseidonius on the coast of the northern Levant. He reports the following: "As for the plains, the first, beginning at the sea, is called Macras, or Macra-Plain. Here, as reported by Poseidonius, was seen the fallen dragon, the corpse of which was about a plethrum [100 feet] in length, and so bulky that horsemen standing by it on either side could not see one another; and its jaws were large enough to admit a man on horseback, and each flake of its horny scales exceeded an oblong shield in length."(Geography, book 16, chapter two, paragraph 17) The creature was seen by Poseidonius, a Philosopher, sometime between 130 and 51 BC.

Hans Egede, the national saint of Greenland, gives an 18th-century description of a sea serpent. On July 6, 1734 his ship sailed past the coast of Greenland when suddenly those on board "saw a most terrible creature, resembling nothing they saw before. The monster lifted its head so high that it seemed to be higher than the crow's nest on the mainmast. The head was small and the body short and wrinkled. The unknown creature was using giant fins which propelled it through the water. Later the sailors saw its tail as well. The monster was longer than our whole ship", wrote Egede. (Mareš, 1997)

Reported sea serpent sightings on the coast of New England have been documented from 1638 onwards. An incident in August 1817 led a committee of the Linnaean Society of New England to give a deformed terrestrial snake the name Scoliophis atlanticus, believing it was the juvenile form of a sea serpent that had recently been reported in Gloucester Harbor.[9] Sworn statements made before a local Justice of the Peace and first published in 1818 were never recanted.[10] After the Linnaean Society's misidentification was discovered, it was frequently cited by debunkers as evidence that the creature did not exist.

A particularly famous sea serpent sighting was made by the officers and men of HMS Daedalus in August 1848 during a voyage to Saint Helena in the South Atlantic; the creature they saw, some 60 feet (18 m) long, held a snakelike head above the water, and Captain Peter M'Quahe's report said "something like the mane of a horse, or rather a bunch of seaweed washed about its back." The sighting caused quite a stir in the London papers, and Sir Richard Owen, the famous English biologist, proclaimed the beast an elephant seal. Other explanations for the sighting proposed that it was an upside-down canoe, or a giant squid.[11]

A sea "monster" was repeatedly sighted in 19th-century County Clare, Ireland, including one in 1850 when it was seen, "sunning itself near the Clare coast off Kilkee". In September 1871, the "large and frightening sea monster" was seen by several people near Kilkee, who "all had their nerves considerably upset by the dreadful appearance of this extraordinary creature." [12]

Another sighting took place in 1905 off the coast of Brazil. The crew of the Valhalla and two naturalists, Michael J. Nicoll and E. G. B. Meade-Waldo, saw a long-necked, turtle-headed creature, with a large squarish or ribbon-like dorsal fin. Based on its dorsal fin and the shape of its head, some (such as Bernard Heuvelmans) have suggested that the animal was some sort of marine mammal. A skeptical suggestion is that the sighting was of a giant squid swimming with one arm and fin visible, but this is problematical, as there are no reports of squid swimming in such a manner, and no apparent reason why one would.

On April 25, 1977, the Japanese trawler Zuiyo Maru, sailing east of Christchurch, New Zealand, caught a strange, apparently unknown creature in the trawl. Photographs and tissue specimens were taken. While initial speculation suggested it might be a prehistoric plesiosaur, analysis later indicated that the body was the carcass of a basking shark.

On October 31, 1983, about 2:00 p.m., five members of a construction crew saw a 100-foot-long sea serpent off Stinson Beach, which is just north of San Francisco, California. A flagman named Gary saw it first swimming towards the cliffside road which the work crew was repairing. He radioed another member of the work crew, Matt Ratto, and told him to grab the binoculars. Ratto began looking at the sea serpent when it was 100 yards offshore and less than a quarter of a mile away. Ratto said, "The body came out of the water first." He added, "It was black with three humps." He continued, "There were three bends. like humps and they rose straight up." He further described it as a "humpy, flat-backed thing". He also made a sketch of the animal which appeared to be a round headed, blunt nosed, snake-like creature followed by 3 vertical arches or coils sticking out of the water. Another eyewitness, Steve Bjora, said "The sucker was going 45 to 50 miles an hour." He also described the animal saying, "It was clipping. It was boogying. It looked like a long eel." Marlene Martin, the Caltran safety engineer who was over seeing the work crew also saw the animal. She said, "It shocked the hell out of me" adding, "That thing's so big he deserves front page coverage." She went on to say, "It was hard to describe how big it was. I have no creative imagination. It was a snake-like thing that arched itself up and was so long it made humps above the water." Martin first saw it near Bolinas and saw it swim the whole way to Stinson beach then watched it turn around and head towards the Farallone Islands. Martin said, "It had a wake as big as a power boat's and it was going about 65 miles an hour. It looked like a great big rubber hose as it moved. If someone had gotten in its way it would have plowed right though them." Before it went underwater Martin saw it lift its head and a portion of its body directly behind its head out of the water then open its mouth. Martin said, "It was like it was playing." She described the animal as a "giant snake or a dragon, with a mouth like an alligator's." She continued, "It was at least 15 or 20 feet in circumference, but it was hard to tell how long it was. I mean, how long is a snake? Marlin Martin concluded by saying, "He should have the whole damn ocean. It's his territory. He's the King of the Sea![13][14][15]

On February 5, 1985, twin brothers Bill and Bob Clark sighted a 60+ foot long sea serpent in San Francisco Bay that crashed onto a submerged rocky ledge only 20 yards away from where they were sitting in their car. It was around 7:45 a.m. and the water was calm. The Clark brothers were sitting in their car drinking coffee when they noticed a group of seals in the water. Then they noticed what they thought was another seal approach the group. The group of seals began to swim away and one of them headed for the seawall where the Clarks were parked. The seals were followed by the creature and according to Bob, "Bill started saying it was moving strange. He said it was not a seal, it's a snake." Bob continued, "We watched it coming in, undulating in a vertical manner. Where most snakes undulate side to side, this was up and down, creating humps in the water. Bob said, "The seals were leaping through the water in front of it. I think it was going to eat them. It was behind the seals arched above the water line and I could tell it was a large animal when the arch appeared to stay in one spot. I could see the body moving through the arch." The Clarks said the water was so clear that morning they could easily see the creature as it undulated at amazing speed like an uncoiling whip. They both estimated the length of the creature to be at least 60 feet. As it swam over the submerged rocky ledge it stopped dead in its tracks then it appeared to slide a few feet across the water creating a light spray. It apparently got stuck on the rocks. Bob said the animal turned clockwise and exposed its midsection. "It turned over like a corkscrew in midsection. We could see the belly of the animal. It reminded me of an alligator stomach, creamy white, soft leathery looking, but with a tint of yellow in it." He continued saying, "After it twisted over and showed the underbelly, another section behind the underbelly came up about three feet out of the water. I got an excellent view of a fin-type appendage, which opened up like an accordion fan. It stayed up about five seconds, long enough for me to tell my brother, 'Bill, I'm going to look at it as long as I can so I can remember it.' " After it twisted the midsection off of the submerged rocky ledge, Bill said they watched the creature sit "motionless in the water for five or ten seconds". Then it began to swim away, using a "violent, downward thrust of its upper neck which sent a pack of coils backwards towards the midsection. After a few seconds of undulations, the creature moved rapidly, just below the surface of the water northward toward deeper water in the middle of the Bay." Bill concluded his account by saying, "I don't care if anyone believes me. I know what I saw. It was too mind-blowing and close to me not to say something about it."[16][17]

Misidentifications

Skeptics have questioned the interpretation of sea serpent sightings, suggesting that reports of serpents are misidentifications of animals such as cetaceans (whales and dolphins), sea snakes, eels, basking sharks, frilled sharks, baleen whales, oarfish, large pinnipeds, seaweed, driftwood, flocks of birds, and giant squid.[18]

While most cryptozoologists recognize that at least some reports are simple misidentifications, they claim that many of the creatures described by those who have seen them look nothing like the known species put forward by skeptics and claim that certain reports stick out. For their part, the skeptics remain unconvinced, pointing out that even in the absence of outright hoaxes, imagination has a way of twisting and inflating the slightly out-of-the-ordinary until it becomes extraordinary.

A recent posting on the Centre of Fortean Zoology blog by Cryptozoologist Dale Drinnon notes his check of the categories in Heuvelmans' In The Wake of the Sea-Serpents, in which he extracted the mistaken observation categories as a control to check the Sea-serpent categories by using the reports he created identikits for the mistaken observations and enlarged them to possibly 126 of Heuvelmans' sightings, making the mistaken observations the largest section of Heuvelmans' reports. His identikits include oarfish, basking sharks, toothed whales, baleen whales, lines of large whales for the largest sea serpent "hump" sightings and trains of smaller cetaceans for the "Many-finned, elephant seals and manta rays. Each of these categories was given a percentage of the whole body of reports, ranging between 1% and 5% with the whales at an average 2.5%, figures which he considers comparable to the regular Sea-serpent categories of Super-eel and Marine Saurian, each of which he breaks into a larger and a smaller sized series following Heuvelmans' suggestion in In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents. [19] Drinnon offered further analysis the 2010 CFZ yearbook.[20] In this article he modified Coleman's categories (below), adding a possible Giant otter category to the Giant Beavers and modifying several others, bringing the total to 17 categories to broaden the coverage. The broadened coverage allows more instances of outsized versions of conventional fishes such as sturgeons and catfishes, left off Coleman's list. In a separate and earlier CFZ blog, Drinnon reviewed Bruce Champagne's sea-serpent categories and argued that several referred to known animals, the whales in particular.[21] Drinnon basically recognises the Longneck, Marine Saurian and Super-eel categories in this blog as well, with the modification that the Marine Saurian as spoken of by Champagne is more likely a large crocodile akin to the saltwater crocodile and that there has been a suggestion that an eel-like animal is involved in certain "Many-finned" observations. The whale categories he identifies are: BC 2A-Possible Odobenocetops, BC2B, Atlantic gray whale or Scrag Whale, BC 4B, as being similar to an unidentified large-finned beaked whale otherwise reported in the Pacific, and BC 5, the large Father-of-All-the-Turtles, as a humpback whale turned turtle.

Classification systems

Cryptozoologists have argued for the existence of sea serpents by claiming that people report seeing similar things, and further arguing that it is possible to classify sightings into different "types". There have been different classification attempts with different results, although they share some common characteristics. Note that although many of these have been given taxonomic Latin names, none have been scientifically identified or examined.

Anthonie Cornelis Oudemans

- Megophias megophias : A large sea lion-like creature with a long neck and long tail. Over 200 feet (61 m) long. Only the male has a mane. It is cosmopolitan.

Bernard Heuvelmans

- Long Necked or Megalotaria longicollis: A 60-foot (18 m), long-necked, short-tailed sea lion. Hair and whiskers reported. Cosmopolitan.

- Merhorse or Halshippus olai-magni: A 60-foot (18 m), medium-necked, large-eyed, horse-headed pinniped. Often has whiskers. It is also cosmopolitan.

- Many-Humped or Plurigibbosus novae-angliae: A 60–100-foot (18–30 m), medium-necked, long-bodied archaeocete. It has a series of humps or a crest on the spine like a sperm whale's or grey whale's. It only lives in the North Atlantic.

- Super Otter or Hyperhydra egedei: A 65–100-foot (20–30 m), medium-necked, long-bodied archaeocete that resembles an otter. It moves in numerous vertical undulations (6-7). Lived near Norway and Greenland, and presumed to be extinct by Heuvelmans.

- Many Finned or Cetioscolopendra aeliani: A 60–70-foot (18–21 m), short necked archeocete. It has a number of lateral projections that look like dorsal fins, but turned the incorrect way. Compare to the armor on Desmatosuchus, but much more prominent.

- Super Eels: A group of large and possibly unrelated eels. Partially based on the Leptocephalus giganteus larvae, later shown to be normal sized. [This is a controversial identification of a larval specimen made without benefit of examining the specimen. This "identification" was done by the paperwork and the specimen was missing by then.] Heuvelmans theorized eel, synbranchid, and elasmobranch identities as being possible. Cosmopolitan.

- Marine Saurian: A 50–60-foot (15–18 m) crocodile, or crocodile-like animal (Mosasaur, Pliosaur, etc.)

- Yellow Belly: A very large, 100–200-foot (30–61 m) yellow-and-black-striped, tadpole-shaped creature. Dropped.

- Father-of-all-the-turtles: A giant turtle. Dropped.

- Giant Invertebrates: Giant Venus's girdle and salp colonies. Added. It is not clear if Heuvelmans intended them to be unknown species or extreme forms of known species.

Loren Coleman and Patrick Huyghe

- Classic Sea Serpent: A quadrupedal, elongated animal with the appearance of many humps when swimming. Essentially a composite of the many humped, super otter, and super eels types. The authors suggest Basilosaurus as a candidate, or possibly Remingtoncetids.

- Waterhorse: A large pinniped, similar to the long necked and merhorse. Only the males are maned, but females appear to have snorkels. Both of their eyes are rather small. They are noteworthy for being behind both salt and fresh water sightings.

- Mystery Cetacean: A category of unknown whale species including double finned whales and dolphins, dorsal finned sperm whales, unknown beaked whales, an unknown orca, and others.

- Giant Shark: A surviving megalodon.

- Mystery Manta: A small manta ray with dorsal markings.

- Great Sea Centipede: Same as the many finned. The authors suggest the flippers may either be retractile, and the "scaly" appearance could be caused by parasites.

- Mystery Saurian: Same as the marine saurian.

- Cryptic Chelonian: A resurrection of the father-of-all-turtles.

- Mystery Sirenian: Late surviving Steller's Sea Cow.

- Giant Octopus, Octopus giganteus or Otoctopus giganteus: A large cephalopod living in the tropical Atlantic.

Bruce Champagne

- 1A Long Necked: A 30-foot (9.1 m) sea lion with a long neck and long tail. The neck is the same thickness or smaller than the head. Hair reported. It is capable of travel on land. Cosmopolitan.

- 1B Long Necked: Similar to the above type but over 55 feet (17 m) long and far more robust. The neck is of lesser thickness than the head. Only inhabits water near Great Britain and Denmark.

- 2A Eel-Like: A 20–30-foot-long (6.1–9.1 m) heavily scaled or armored reptile. It is distinguished by a small square head with prominent tusks. "Motorboating" behavior on surface. Inhabits only the North Atlantic.

- 2B Eel-Like: A 25–30-foot (7.6–9.1 m) beaked whale. It is distinguished by a tapering head and a dorsal crest. "Motorboating" behavior engaged in. Inhabits the Atlantic and Pacific. Possibly extinct.

- 2C Eel-Like: A 60–70-foot (18–21 m), elongated reptile with no appendages. The head is very large and cow-like or reptilian with teeth similar to a crabeater seal's. Also shares the "motorboating" behavior. Inhabits the Atlantic, Pacific, and South China Sea. Possibly extinct.

- 3 Multi-Humped: 30–60 feet (9.1–18.3 m) long. A possible reptile with a dorsal crest and the ability to move in several undulations. The head has a distinctive "cameloid" appearance. Identical with Cadborosaurus willsi.

- 4A Sailfin: A 30–70-foot (9.1–21.3 m) beaked whale. It is distinguished by a very small head and a very large dorsal fin. Only found in the North West Atlantic. Possibly extinct.

- 4B Sailfin: An elongated animal of possible mammalian or reptilian identity reported to be 12–85 feet (3.7–25.9 m) long. It has a long neck with a turtle-like head and a long continuous dorsal fin. Cosmopolitan.

- 5 Carapaced: A large turtle or turtle-like creature (mammal?) reported to be 10–45 feet (3.0–13.7 m) long. Carapace is described as jointed, segmented, and plated. May exhibit a dorsal crest of "quills" and a type of oily hair. Cosmopolitan.

- 6 Saurian: A large and occasionally spotted crocodile or crocodile-like creature up to 65 feet (20 m) long. Found in the Northern Atlantic and Mediterranean.

- 7 Segmented/Multi limbed: An elongated mammalian creature up to 65 feet (20 m) long with the appearance of segmentation and many fins. Found in the Western Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific.

See also

References

- ↑ Bruce Champagne. Craig Heinselman, ed. "A Preliminary Evaluation of a Study of the Morphology, Behavior, Autoecology, and Habitat of Large, Unidentified Marine Animals, Based on Recorded Field Observations" (PDF). Crypto. Dracontology (1): 99–118. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ↑ Sue Hamilton, Monsters, page 24 (ABDO Publishing Company, 2007). ISBN 978-1-59928-771-3

- ↑ "Sea Serpent?". By Ask.com. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ↑ "The Unexplained Mystery of the Sea Serpent". By Crypted Chronicles (March 18, 2012). Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ↑ "Ormen i Syltefjellet". Archived from the original on 2011-07-24.

- ↑ "Galleri NOR". Nb.no. Retrieved 2014-07-10.

- ↑ "Norse Mythology - Jormungandr". By Oracle Thinkquest. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ↑ Water Monsters. Gail B. Stewart (author of the book) of Google Books. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ↑ Linnaean Society of New England (1817). Report of a Committee of the Linnaean Society of New England, relative to a large marine animal, supposed to be a serpent, seen near Cape Ann, Massachusetts, in August 1817. Boston: Cummings and Hilliard.

- ↑ Soini, Wayne. Gloucester's Sea Serpent. Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-59629-461-5.

- ↑ Eyers, Jonathan (2011). Don't Shoot the Albatross!: Nautical Myths and Superstitions. A&C Black, London, UK. ISBN 978-1-4081-3131-2.

- ↑ Parsons, Michael. "Possible Ireland’s Loch Ness monster resurfaces after 144 years". Irish Times. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Sea Serpent Caught on Paper", "San Francisco Chronicle" (3 November 1983) P. ?.

- ↑ "Coastal Post, Vol. 8, NO. 45" (7 November 1983) p. ?.

- ↑ "Stinson Sea Serpent Spurs Skepticism", "Point Reyes Light" (14 November 1983) P. ?.

- ↑ "Twins Sight Sea Serpent '60 Feet Long' off Marina". "San Francisco Examiner" (20 February 1985) P. 3.

- ↑ "Is Bay Snake The Coastal Sea Serpent?", "Coastal Post" (Vol. 10, Number 8, 25 February - 4 March 1985) P. ?.

- ↑ "The UnMuseum - Sea Monsters that Weren't". unmuseum.org.

- ↑ "CRYPTOZOOLOGY ONLINE: Still on the Track: DALE DRINNON: Extractions from Heuvelmans, In The Wake of the Sea-Serpents, "Mistaken Observations" Category". Forteanzoology.blogspot.com. 2010-06-10. Retrieved 2014-07-10.

- ↑ Drinnon, Dale A, "A preliminary Cryptozoological Checklist, p 85-126. CFZ Press, Myrtle Cottage, Devon, UK 2010

- ↑ http://forteanzoology.blogspot.com/search?q=Dale+Drinnon, DALE DRINNON: Possible Identifications for some of Bruce Champagne's Independent Sea-Serpent Classification Categories, blog of May 25, 2010

Further reading

- Coleman, Loren; Huyghe, Patrick (2003). The Field Guide to Lake Monsters, Sea Serpents, and Other Mystery Denizens of the Deep. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher. ISBN 1-58542-252-5.

- Lyons, Sherrie Lynne (2010). Species, Serpents, Spirits, and Skulls: Science at the Margins in the Victorian Age. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-2802-4.

- O'Neill, J.P. (2003). The great New England sea serpent : an account of unknown creatures sighted by many respectable persons between 1638 and the present day. New York: Paraview. ISBN 978-1931044677.

- Oudemans, A. C. (1892). The Great Sea Serpent (PDF). Luzac & Co.

- Mareš, J. (1997). Svět tajemných zvířat (in Czech). Prague. ISBN 80-85916-16-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sea serpent. |

- Video of the oarfish, a creature that inspired the sea serpent mythology.

- A sea serpent in Iceland

- Clark brothers blog about sightings of sea serpents in and near SF Bay