Mathematics of paper folding

The art of origami or paper folding has received a considerable amount of mathematical study. Fields of interest include a given paper model's flat-foldability (whether the model can be flattened without damaging it) and the use of paper folds to solve mathematical equations.

History

In 1893, Indian mathematician T. Sundara Rao published "Geometric Exercises in Paper Folding" which used paper folding to demonstrate proofs of geometrical constructions.[1] This work was inspired by the use of origami in the kindergarten system. This book had an approximate trisection of angles and implied construction of a cube root was impossible. In 1936 Margharita P. Beloch showed that use of the 'Beloch fold', later used in the sixth of the Huzita–Hatori axioms, allowed the general cubic equation to be solved using origami.[2] In 1949, R C Yeates' book "Geometric Methods" described three allowed constructions corresponding to the first, second, and fifth of the Huzita–Hatori axioms.[3][4] The axioms were discovered by Jacques Justin in 1989.[5] but were overlooked until the first six were rediscovered by Humiaki Huzita in 1991. The first International Meeting of Origami Science and Technology (now known as the International Conference on Origami in Science, Math, and Education) was held in 1989 in Ferrara, Italy.

Pure origami

Flat folding

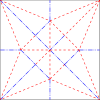

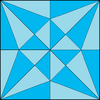

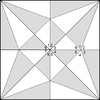

The construction of origami models is sometimes shown as crease patterns. The major question about such crease patterns is whether a given crease pattern can be folded to a flat model, and if so, how to fold them; this is an NP-complete problem.[6] Related problems when the creases are orthogonal are called map folding problems. There are three mathematical rules for producing flat-foldable origami crease patterns:[7]

- Maekawa's theorem: at any vertex the number of valley and mountain folds always differ by two.

- It follows from this that every vertex has an even number of creases, and therefore also the regions between the creases can be colored with two colors.

- Kawasaki's theorem: at any vertex, the sum of all the odd angles adds up to 180 degrees, as do the even.

- A sheet can never penetrate a fold.

Paper exhibits zero Gaussian curvature at all points on its surface, and only folds naturally along lines of zero curvature. Curved surfaces that can't be flattened can be produced using a non-folded crease in the paper, as is easily done with wet paper or a fingernail.

Assigning a crease pattern mountain and valley folds in order to produce a flat model has been proven by Marshall Bern and Barry Hayes to be NP-complete.[8] Further references and technical results are discussed in Part II of Geometric Folding Algorithms.[9]

Huzita–Hatori axioms

Some classical construction problems of geometry — namely trisecting an arbitrary angle or doubling the cube — are proven to be unsolvable using compass and straightedge, but can be solved using only a few paper folds.[10] Paper fold strips can be constructed to solve equations up to degree 4. The Huzita–Hatori axioms are an important contribution to this field of study. These describe what can be constructed using a sequence of creases with at most two point or line alignments at once. Complete methods for solving all equations up to degree 4 by applying methods satisfying these axioms are discussed in detail in Geometric Origami.[11]

Constructions

As a result of origami study through the application of geometric principles, methods such as Haga's theorem have allowed paperfolders to accurately fold the side of a square into thirds, fifths, sevenths, and ninths. Other theorems and methods have allowed paperfolders to get other shapes from a square, such as equilateral triangles, pentagons, hexagons, and special rectangles such as the golden rectangle and the silver rectangle. Methods for folding most regular polygons up to and including the regular 19-gon have been developed.[11]

Haga's theorems

The side of a square can be divided at an arbitrary rational fraction in a variety of ways. Haga's theorems say that a particular set of constructions can be used for such divisions.[12] Surprisingly few folds are necessary to generate large odd fractions. For instance 1⁄5 can be generated with three folds; first halve a side, then use Haga's theorem twice to produce first 2⁄3 and then 1⁄5.

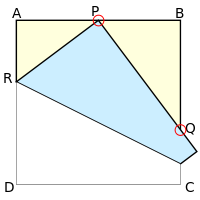

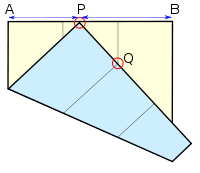

The accompanying diagram shows Haga's first theorem:

The function changing the length AP to QC is self inverse. Let x be AP then a number of other lengths are also rational functions of x. For example:

| AP | BQ | QC | AR | PQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1⁄2 | 2⁄3 | 1⁄3 | 3⁄8 | 5⁄6 |

| 1⁄3 | 1⁄2 | 1⁄2 | 4⁄9 | 5⁄6 |

| 2⁄3 | 4⁄5 | 1⁄5 | 5⁄18 | 13⁄15 |

| 1⁄5 | 1⁄3 | 2⁄3 | 12⁄25 | 13⁄15 |

Doubling the cube

The classical problem of doubling the cube can be solved using origami. This construction is due to Peter Messer:[13] A square of paper is first creased into three equal strips as shown in the diagram. Then the bottom edge is positioned so the corner point P is on the top edge and the crease mark on the edge meets the other crease mark Q. The length PB will then be the cube root of 2 times the length of AP.[14]

The edge with the crease mark is considered a marked straightedge, something which is not allowed in compass and straightedge constructions. Using a marked straightedge in this way is called a neusis construction in geometry.

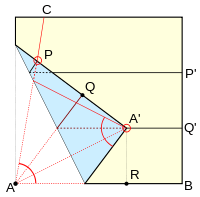

Trisecting an angle

Angle trisection is another of the classical problems that cannot be solved using a compass and unmarked ruler but can be solved using origami. This construction is due to Hisashi Abe.[13] The angle CAB is trisected by making folds PP' and QQ' parallel to the base with QQ' halfway in between. Then point P is folded over to lie on line AC and at the same time point A is made to lie on line QQ' at A'. The angle A'AB is one third of the original angle CAB. This is because PAQ, A'AQ and A'AR are three congruent triangles. Aligning the two points on the two lines is another neusis construction as in the solution to doubling the cube.[15]

Related problems

The problem of rigid origami, treating the folds as hinges joining two flat, rigid surfaces, such as sheet metal, has great practical importance. For example, the Miura map fold is a rigid fold that has been used to deploy large solar panel arrays for space satellites.

The napkin folding problem is the problem of whether a square or rectangle of paper can be folded so the perimeter of the flat figure is greater than that of the original square.

Curved origami also poses a (very different) set of mathematical challenges.[16] Curved origami allows the paper to form developable surfaces that are not flat.

Wet-folding origami allows an even greater range of shapes.

The maximum number of times an incompressible material can be folded has been derived. With each fold a certain amount of paper is lost to potential folding. The loss function for folding paper in half in a single direction was given to be , where L is the minimum length of the paper (or other material), t is the material's thickness, and n is the number of folds possible.[17] The distances L and t must be expressed in the same units, such as inches. This result was derived by Gallivan in 2001, who also folded a sheet of paper in half 12 times, contrary to the popular belief that paper of any size could be folded at most eight times. She also derived the equation for folding in alternate directions.[18]

The fold-and-cut problem asks what shapes can be obtained by folding a piece of paper flat, and making a single straight complete cut. The solution, known as the fold-and-cut theorem, states that any shape with straight sides can be obtained.

A practical problem is how to fold a map so that it may be manipulated with minimal effort or movements. The Miura fold is a solution to the problem, and several others have been proposed.[19]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Origami mathematics. |

- Flexagon

- Lill's method

- Napkin folding problem

- Map folding

- Regular paperfolding sequence (for example, the dragon curve)

Notes and references

- ↑ T. Sundara Rao (1893). Geometric Exercises in Paper Folding. Addison.

- ↑ Hull, Thomas C. (2011). "Solving cubics with creases: the work of Beloch and Lill" (PDF). American Mathematical Monthly. 118 (4): 307–315. MR 2800341. doi:10.4169/amer.math.monthly.118.04.307.

- ↑ George Edward Martin (1997). Geometric constructions. Springer. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-387-98276-2.

- ↑ Robert Carl Yeates (1949). Geometric Tools. Louisiana State University.

- ↑ Justin, Jacques, "Resolution par le pliage de l'equation du troisieme degre et applications geometriques", reprinted in Proceedings of the First International Meeting of Origami Science and Technology, H. Huzita ed. (1989), pp. 251–261.

- ↑ Thomas C. Hull (2002). "The Combinatorics of Flat Folds: a Survey" (PDF). The Proceedings of the Third International Meeting of Origami Science, Mathematics, and Education. AK Peters. ISBN 978-1-56881-181-9.

- ↑ "Robert Lang folds way-new origami".

- ↑ Bern, Marshall; Hayes, Barry (1996). "The complexity of flat origami". Proceedings of the Seventh Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (Atlanta, GA, 1996). ACM, New York. pp. 175–183. MR 1381938.

- ↑ Demaine, Erik D.; O'Rourke, Joseph (2007). Geometric folding algorithms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85757-4. MR 2354878. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511735172.

- ↑ Tom Hull. "Origami and Geometric Constructions".

- 1 2 Geretschläger, Robert (2008). Geometric Origami. UK: Arbelos. ISBN 978-0-9555477-1-3.

- ↑ Koshiro. "How to Divide the Side of Square Paper". Japan Origami Academic Society.

- 1 2 Lang, Robert J (2008). "From Flapping Birds to Space Telescopes: The Modern Science of Origami" (PDF). Usenix Conference, Boston, MA.

- ↑ Peter Messer (1986). "Problem 1054". Crux Mathematicorum. 12 (10): 284–285.

- ↑ Michael J Winckler; Kathrin D Wold; Hans Georg Bock (2011). "Hands-On Geometry with Origami". Origami 5. CRC Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-56881-714-9.

- ↑ Siggraph: "Curved Origami"

- ↑ Korpal, Gaurish (25 November 2015). "Folding Paper in Half". At Right Angles. 4 (3): 20–23.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Folding". MathWorld.

- ↑ Hull, Thomas (2002). "In search of a practical map fold". Math Horizons. 3 (3): 22–24. JSTOR 25678354.

Further reading

- Demaine, Erik D., "Folding and Unfolding", PhD thesis, Department of Computer Science, University of Waterloo, 2001.

- Haga, Kazuo (2008). Fonacier, Josefina C; Isoda, Masami, eds. Origamics: Mathematical Explorations Through Paper Folding. University of Tsukuba, Japan: World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 978-981-283-490-4.

- Lang, Robert J. (2003). Origami Design Secrets: Mathematical Methods for an Ancient Art. A K Peters. ISBN 1-56881-194-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Origami mathematics. |

- Dr. Tom Hull. "Origami Mathematics Page".

- Paper Folding Geometry at cut-the-knot

- Dividing a Segment into Equal Parts by Paper Folding at cut-the-knot

- Britney Gallivan has solved the Paper Folding Problem

- Overview of Origami Axioms