Angle

| Basic angle types |

| Types of angles

2D angles 2D angle pairs 3D angles |

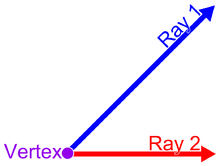

In planar geometry, an angle is the figure formed by two rays, called the sides of the angle, sharing a common endpoint, called the vertex of the angle.[1] Angles formed by two rays lie in a plane, but this plane does not have to be a Euclidean plane. Angles are also formed by the intersection of two planes in Euclidean and other spaces. These are called dihedral angles. Angles formed by the intersection of two curves in a plane are defined as the angle determined by the tangent rays at the point of intersection. Similar statements hold in space, for example, the spherical angle formed by two great circles on a sphere is the dihedral angle between the planes determined by the great circles.

Angle is also used to designate the measure of an angle or of a rotation. This measure is the ratio of the length of a circular arc to its radius. In the case of a geometric angle, the arc is centered at the vertex and delimited by the sides. In the case of a rotation, the arc is centered at the center of the rotation and delimited by any other point and its image by the rotation.

The word angle comes from the Latin word angulus, meaning "corner"; cognate words are the Greek ἀγκύλος (ankylοs), meaning "crooked, curved," and the English word "ankle". Both are connected with the Proto-Indo-European root *ank-, meaning "to bend" or "bow".[2]

Euclid defines a plane angle as the inclination to each other, in a plane, of two lines which meet each other, and do not lie straight with respect to each other. According to Proclus an angle must be either a quality or a quantity, or a relationship. The first concept was used by Eudemus, who regarded an angle as a deviation from a straight line; the second by Carpus of Antioch, who regarded it as the interval or space between the intersecting lines; Euclid adopted the third concept, although his definitions of right, acute, and obtuse angles are certainly quantitative.[3]

Identifying angles

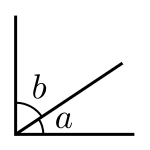

In mathematical expressions, it is common to use Greek letters (α, β, γ, θ, φ, . . . ) to serve as variables standing for the size of some angle. (To avoid confusion with its other meaning, the symbol π is typically not used for this purpose.) Lower case Roman letters (a, b, c, . . . ) are also used, as are upper case Roman letters in the context of polygons. See the figures in this article for examples.

In geometric figures, angles may also be identified by the labels attached to the three points that define them. For example, the angle at vertex A enclosed by the rays AB and AC (i.e. the lines from point A to point B and point A to point C) is denoted ∠BAC or Sometimes, where there is no risk of confusion, the angle may be referred to simply by its vertex ("angle A").

Potentially, an angle denoted, say, ∠BAC might refer to any of four angles: the clockwise angle from B to C, the anticlockwise angle from B to C, the clockwise angle from C to B, or the anticlockwise angle from C to B, where the direction in which the angle is measured determines its sign (see Positive and negative angles). However, in many geometrical situations it is obvious from context that the positive angle less than or equal to 180 degrees is meant, and no ambiguity arises. Otherwise, a convention may be adopted so that ∠BAC always refers to the anticlockwise (positive) angle from B to C, and ∠CAB to the anticlockwise (positive) angle from C to B.

Types of angles

Individual angles

- Angles smaller than a right angle (less than 90°) are called acute angles ("acute" meaning "sharp").

- An angle equal to 1/4 turn (90° or π/2 radians) is called a right angle. Two lines that form a right angle are said to be normal, orthogonal, or perpendicular.

- Angles larger than a right angle and smaller than a straight angle (between 90° and 180°) are called obtuse angles ("obtuse" meaning "blunt").

- An angle equal to 1/2 turn (180° or π radians) is called a straight angle.

- Angles larger than a straight angle but less than 1 turn (between 180° and 360°) are called reflex angles.

- An angle equal to 1 turn (360° or 2π radians) is called a full angle, complete angle, or a perigon.

- Angles that are not right angles or a multiple of a right angle are called oblique angles.

The names, intervals, and measured units are shown in a table below:

| Name | acute | right angle | obtuse | straight | reflex | perigon | ||||

| Units | Interval | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turns | (0, 1/4) | 1/4 | (1/4, 1/2) | 1/2 | (1/2, 1) | 1 | ||||

| Radians | (0, 1/2π) | 1/2π | (1/2π, π) | π | (π, 2π) | 2π | ||||

| Degrees | (0, 90)° | 90° | (90, 180)° | 180° | (180, 360)° | 360° | ||||

| Gons | (0, 100)g | 100g | (100, 200)g | 200g | (200, 400)g | 400g | ||||

Equivalence angle pairs

- Angles that have the same measure (i.e. the same magnitude) are said to be equal or congruent. An angle is defined by its measure and is not dependent upon the lengths of the sides of the angle (e.g. all right angles are equal in measure).

- Two angles which share terminal sides, but differ in size by an integer multiple of a turn, are called coterminal angles.

- A reference angle is the acute version of any angle determined by repeatedly subtracting or adding straight angle (1/2 turn, 180°, or π radians), to the results as necessary, until the magnitude of result is an acute angle, a value between 0 and 1/4 turn, 90°, or π/2 radians. For example, an angle of 30 degrees has a reference angle of 30 degrees, and an angle of 150 degrees also has a reference angle of 30 degrees (180 – 150). An angle of 750 degrees has a reference angle of 30 degrees (750 – 720).[4]

Vertical and adjacent angle pairs

When two straight lines intersect at a point, four angles are formed. Pairwise these angles are named according to their location relative to each other.

- A pair of angles opposite each other, formed by two intersecting straight lines that form an "X"-like shape, are called vertical angles or opposite angles or vertically opposite angles. They are abbreviated as vert. opp. ∠s.[5]

- The equality of vertically opposite angles is called the vertical angle theorem. Eudemus of Rhodes attributed the proof to Thales of Miletus.[6][7] The proposition showed that since both of a pair of vertical angles are supplementary to both of the adjacent angles, the vertical angles are equal in measure. According to a historical Note,[7] when Thales visited Egypt, he observed that whenever the Egyptians drew two intersecting lines, they would measure the vertical angles to make sure that they were equal. Thales concluded that one could prove that all vertical angles are equal if one accepted some general notions such as: all straight angles are equal, equals added to equals are equal, and equals subtracted from equals are equal.

- In the figure, assume the measure of Angle A = x. When two adjacent angles form a straight line, they are supplementary. Therefore, the measure of Angle C = 180 − x. Similarly, the measure of Angle D = 180 − x. Both Angle C and Angle D have measures equal to 180 − x and are congruent. Since Angle B is supplementary to both Angles C and D, either of these angle measures may be used to determine the measure of Angle B. Using the measure of either Angle C or Angle D we find the measure of Angle B = 180 − (180 − x) = 180 − 180 + x = x. Therefore, both Angle A and Angle B have measures equal to x and are equal in measure.

- Adjacent angles, often abbreviated as adj. ∠s, are angles that share a common vertex and edge but do not share any interior points. In other words, they are angles that are side by side, or adjacent, sharing an "arm". Adjacent angles which sum to a right angle, straight angle or full angle are special and are respectively called complementary, supplementary and explementary angles (see "Combine angle pairs" below).

A transversal is a line that intersects a pair of (often parallel) lines and is associated with alternate interior angles, corresponding angles, interior angles, and exterior angles.[8]

Combining angle pairs

There are three special angle pairs which involve the summation of angles:

- Complementary angles are angle pairs whose measures sum to one right angle (1/4 turn, 90°, or π/2 radians). If the two complementary angles are adjacent their non-shared sides form a right angle. In Euclidean geometry, the two acute angles in a right triangle are complementary, because the sum of internal angles of a triangle is 180 degrees, and the right angle itself accounts for ninety degrees.

- The adjective complementary is from Latin complementum, associated with the verb complere, "to fill up". An acute angle is "filled up" by its complement to form a right angle.

- The difference between an angle and a right angle is termed the complement of the angle.[9]

- If angles A and B are complementary, the following relationships hold:

- (The tangent of an angle equals the cotangent of its complement and its secant equals the cosecant of its complement.)

- The prefix "co-" in the names of some trigonometric ratios refers to the word "complementary".

- Two angles that sum to a straight angle (1/2 turn, 180°, or π radians) are called supplementary angles.

- If the two supplementary angles are adjacent (i.e. have a common vertex and share just one side), their non-shared sides form a straight line. Such angles are called a linear pair of angles.[10] However, supplementary angles do not have to be on the same line, and can be separated in space. For example, adjacent angles of a parallelogram are supplementary, and opposite angles of a cyclic quadrilateral (one whose vertices all fall on a single circle) are supplementary.

- If a point P is exterior to a circle with center O, and if the tangent lines from P touch the circle at points T and Q, then ∠TPQ and ∠TOQ are supplementary.

- The sines of supplementary angles are equal. Their cosines and tangents (unless undefined) are equal in magnitude but have opposite signs.

- In Euclidean geometry, any sum of two angles in a triangle is supplementary to the third, because the sum of internal angles of a triangle is a straight angle.

- Two angles that sum to a complete angle (1 turn, 360°, or 2π radians) are called explementary angles or conjugate angles.

- The difference between an angle and a complete angle is termed the explement of the angle or conjugate of an angle.

Polygon related angles

- An angle that is part of a simple polygon is called an interior angle if it lies on the inside of that simple polygon. A simple concave polygon has at least one interior angle that is a reflex angle.

- In Euclidean geometry, the measures of the interior angles of a triangle add up to π radians, 180°, or 1/2 turn; the measures of the interior angles of a simple convex quadrilateral add up to 2π radians, 360°, or 1 turn. In general, the measures of the interior angles of a simple convex polygon with n sides add up to (n − 2)π radians, or 180(n − 2) degrees, (2n − 4) right angles, or (n/2 − 1) turn.

- The supplement of an interior angle is called an exterior angle, that is, an interior angle and an exterior angle form a linear pair of angles. There are two exterior angles at each vertex of the polygon, each determined by extending one of the two sides of the polygon that meet at the vertex; these two angles are vertical angles and hence are equal. An exterior angle measures the amount of rotation one has to make at a vertex to trace out the polygon.[11] If the corresponding interior angle is a reflex angle, the exterior angle should be considered negative. Even in a non-simple polygon it may be possible to define the exterior angle, but one will have to pick an orientation of the plane (or surface) to decide the sign of the exterior angle measure.

- In Euclidean geometry, the sum of the exterior angles of a simple convex polygon will be one full turn (360°). The exterior angle here could be called a supplementary exterior angle. Exterior angles are commonly used in Logo Turtle Geometry when drawing regular polygons.

- In a triangle, the bisectors of two exterior angles and the bisector of the other interior angle are concurrent (meet at a single point).[12]:p.149

- In a triangle, three intersection points, each of an external angle bisector with the opposite extended side, are collinear.[12]:p. 149

- In a triangle, three intersection points, two of them between an interior angle bisector and the opposite side, and the third between the other exterior angle bisector and the opposite side extended, are collinear.[12]:p. 149

- Some authors use the name exterior angle of a simple polygon to simply mean the explement exterior angle (not supplement!) of the interior angle.[13] This conflicts with the above usage.

Plane related angles

- The angle between two planes (such as two adjacent faces of a polyhedron) is called a dihedral angle.[14] It may be defined as the acute angle between two lines normal to the planes.

- The angle between a plane and an intersecting straight line is equal to ninety degrees minus the angle between the intersecting line and the line that goes through the point of intersection and is normal to the plane.

Measuring angles

The size of a geometric angle is usually characterized by the magnitude of the smallest rotation that maps one of the rays into the other. Angles that have the same size are said to be equal or congruent or equal in measure.

In some contexts, such as identifying a point on a circle or describing the orientation of an object in two dimensions relative to a reference orientation, angles that differ by an exact multiple of a full turn are effectively equivalent. In other contexts, such as identifying a point on a spiral curve or describing the cumulative rotation of an object in two dimensions relative to a reference orientation, angles that differ by a non-zero multiple of a full turn are not equivalent.

In order to measure an angle θ, a circular arc centered at the vertex of the angle is drawn, e.g. with a pair of compasses. The ratio of the length s of the arc by the radius r of the circle is the measure of the angle in radians.

The measure of the angle in another angular unit is then obtained by multiplying its measure in radians by the scaling factor k/2π, where k is the measure of a complete turn in the chosen unit (for example 360 for degrees or 400 for gradians):

The value of θ thus defined is independent of the size of the circle: if the length of the radius is changed then the arc length changes in the same proportion, so the ratio s/r is unaltered. (Proof. The formula above can be rewritten as k = θr/s. One turn, for which θ = n units, corresponds to an arc equal in length to the circle's circumference, which is 2πr, so s = 2πr. Substituting n for θ and 2πr for s in the formula, results in k = nr/2πr = n/2π.) [Note 1]

Angle addition postulate

The angle addition postulate states that if B is in the interior of angle AOC, then

The measure of the angle AOC is the sum of the measure of angle AOB and the measure of angle BOC. In this postulate it does not matter in which unit the angle is measured as long as each angle is measured in the same unit.

Units

Units used to represent angles are listed below in descending magnitude order. Of these units, the degree and the radian are by far the most commonly used. Angles expressed in radians are dimensionless for the purposes of dimensional analysis.

Most units of angular measurement are defined such that one turn (i.e. one full circle) is equal to n units, for some whole number n. The two exceptions are the radian and the diameter part.

- Turn (n = 1)

- The turn, also cycle, full circle, revolution, and rotation, is complete circular movement or measure (as to return to the same point) with circle or ellipse. A turn is abbreviated τ, cyc, rev, or rot depending on the application, but in the acronym rpm (revolutions per minute), just r is used. A turn of n units is obtained by setting k = 1/2π in the formula above. The equivalence of 1 turn is 360°, 2π rad, 400 grad, and 4 right angles. The symbol τ can also be used as a mathematical constant to represent 2π radians. Used in this way (k = τ/2π) allows for radians to be expressed as a fraction of a turn. For example, half a turn is τ/2 = π.

- Quadrant (n = 4)

- The quadrant is 1/4 of a turn, i.e. a right angle. It is the unit used in Euclid's Elements. 1 quad. = 90° = π/2 rad = 1/4 turn = 100 grad. In German the symbol ∟ has been used to denote a quadrant.

- Sextant (n = 6)

- The sextant (angle of the equilateral triangle) is 1/6 of a turn. It was the unit used by the Babylonians,[16] and is especially easy to construct with ruler and compasses. The degree, minute of arc and second of arc are sexagesimal subunits of the Babylonian unit. 1 Babylonian unit = 60° = π/3 rad ≈ 1.047197551 rad.

- Radian (n = 2π = 6.283 . . . )

- The radian is the angle subtended by an arc of a circle that has the same length as the circle's radius. The case of radian for the formula given earlier, a radian of n = 2π units is obtained by setting k = 2π/2π = 1. One turn is 2π radians, and one radian is 180/π degrees, or about 57.2958 degrees. The radian is abbreviated rad, though this symbol is often omitted in mathematical texts, where radians are assumed unless specified otherwise. When radians are used angles are considered as dimensionless. The radian is used in virtually all mathematical work beyond simple practical geometry, due, for example, to the pleasing and "natural" properties that the trigonometric functions display when their arguments are in radians. The radian is the (derived) unit of angular measurement in the SI system.

- Clock position (n = 12)

- A clock position is the relative direction of an object described using the analogy of a 12-hour clock. One imagines a clock face lying either upright or flat in front of oneself, and identifies the twelve hour markings with the directions in which they point.

- Hour angle (n = 24)

- The astronomical hour angle is 1/24 of a turn. Since this system is amenable to measuring objects that cycle once per day (such as the relative position of stars), the sexagesimal subunits are called minute of time and second of time. Note that these are distinct from, and 15 times larger than, minutes and seconds of arc. 1 hour = 15° = π/12 rad = 1/6 quad. = 1/24 turn = 16 2/3 grad.

- (Compass) point or wind (n = 32)

- The point, used in navigation, is 1/32 of a turn. 1 point = 1/8 of a right angle = 11.25° = 12.5 grad. Each point is subdivided in four quarter-points so that 1 turn equals 128 quarter-points.

- Hexacontade (n = 60)

- The hexacontade is a unit of 6° that Eratosthenes used, so that a whole turn was divided into 60 units.

- Pechus (n = 144–180)

- –The pechus was a Babylonian unit equal to about 2° or 2 1/2°.

- Binary degree (n = 256)

- The binary degree, also known as the binary radian (or brad), is 1/256 of a turn.[17] The binary degree is used in computing so that an angle can be efficiently represented in a single byte (albeit to limited precision). Other measures of angle used in computing may be based on dividing one whole turn into 2n equal parts for other values of n.[18]

- Degree (n = 360)

- The degree, denoted by a small superscript circle (°), is 1/360 of a turn, so one turn is 360°. The case of degrees for the formula given earlier, a degree of n = 360° units is obtained by setting k = 360°/2π. One advantage of this old sexagesimal subunit is that many angles common in simple geometry are measured as a whole number of degrees. Fractions of a degree may be written in normal decimal notation (e.g. 3.5° for three and a half degrees), but the "minute" and "second" sexagesimal subunits of the "degree-minute-second" system are also in use, especially for geographical coordinates and in astronomy and ballistics:

- Diameter part (n = 376.99 . . . )

- The diameter part (occasionally used in Islamic mathematics) is 1/60 radian. One "diameter part" is approximately 0.95493°. There are about 376.991 diameter parts per turn.

- Grad (n = 400)

- The grad, also called grade, gradian, or gon, is 1/400 of a turn, so a right angle is 100 grads. It is a decimal subunit of the quadrant. A kilometre was historically defined as a centi-grad of arc along a great circle of the Earth, so the kilometer is the decimal analog to the sexagesimal nautical mile. The grad is used mostly in triangulation.

- Mil (n = 6000–6400)

- The mil is any of several units that are approximately equal to a milliradian. There are several definitions ranging from 0.05625 to 0.06 degrees (3.375 to 3.6 minutes), with the milliradian being approximately 0.05729578 degrees (3.43775 minutes). In NATO countries, it is defined as 1/6400 of a circle. Its value is approximately equal to the angle subtended by a width of 1 metre as seen from 1 km away (2π/6400 = 0.0009817 . . . ≈ 1/1000).

- Minute of arc (n = 21,600)

- The minute of arc (or MOA, arcminute, or just minute) is 1/60 of a degree = 1/21,600 turn. It is denoted by a single prime ( ′ ). For example, 3° 30′ is equal to 3 × 60 + 30 = 210 minutes or 3 + 30/60 = 3.5 degrees. A mixed format with decimal fractions is also sometimes used, e.g. 3° 5.72′ = 3 + 5.72/60 degrees. A nautical mile was historically defined as a minute of arc along a great circle of the Earth.

- Second of arc (n = 1,296,000)

- The second of arc (or arcsecond, or just second) is 1/60 of a minute of arc and 1/3600 of a degree. It is denoted by a double prime ( ″ ). For example, 3° 7′ 30″ is equal to 3 + 7/60 + 30/3600 degrees, or 3.125 degrees.

Positive and negative angles

Although the definition of the measurement of an angle does not support the concept of a negative angle, it is frequently useful to impose a convention that allows positive and negative angular values to represent orientations and/or rotations in opposite directions relative to some reference.

In a two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system, an angle is typically defined by its two sides, with its vertex at the origin. The initial side is on the positive x-axis, while the other side or terminal side is defined by the measure from the initial side in radians, degrees, or turns. With positive angles representing rotations toward the positive y-axis and negative angles representing rotations toward the negative y-axis. When Cartesian coordinates are represented by standard position, defined by the x-axis rightward and the y-axis upward, positive rotations are anticlockwise and negative rotations are clockwise.

In many contexts, an angle of −θ is effectively equivalent to an angle of "one full turn minus θ". For example, an orientation represented as −45° is effectively equivalent to an orientation represented as 360° − 45° or 315°. Although the final position is the same, a physical rotation (movement) of −45° is not the same as a rotation of 315° (for example, the rotation of a person holding a broom resting on a dusty floor would leave visually different traces of swept regions on the floor).

In three-dimensional geometry, "clockwise" and "anticlockwise" have no absolute meaning, so the direction of positive and negative angles must be defined relative to some reference, which is typically a vector passing through the angle's vertex and perpendicular to the plane in which the rays of the angle lie.

In navigation, bearings are measured relative to north. By convention, viewed from above, bearing angles are positive clockwise, so a bearing of 45° corresponds to a north-east orientation. Negative bearings are not used in navigation, so a north-west orientation corresponds to a bearing of 315°.

Alternative ways of measuring the size of an angle

There are several alternatives to measuring the size of an angle by the angle of rotation. The grade of a slope, or gradient is equal to the tangent of the angle, or sometimes (rarely) the sine. A gradient is often expressed as a percentage. For very small values (less than 5%), the grade of a slope is approximately the measure of the angle in radians.

In rational geometry the spread between two lines is defined at the square of the sine of the angle between the lines. Since the sine of an angle and the sine of its supplementary angle are the same, any angle of rotation that maps one of the lines into the other leads to the same value for the spread between the lines.

Astronomical approximations

Astronomers measure angular separation of objects in degrees from their point of observation.

- 0.5° is approximately the width of the sun or moon.

- 1° is approximately the width of a little finger at arm's length.

- 10° is approximately the width of a closed fist at arm's length.

- 20° is approximately the width of a handspan at arm's length.

These measurements clearly depend on the individual subject, and the above should be treated as rough rule of thumb approximations only.

Angles between curves

The angle between a line and a curve (mixed angle) or between two intersecting curves (curvilinear angle) is defined to be the angle between the tangents at the point of intersection. Various names (now rarely, if ever, used) have been given to particular cases:—amphicyrtic (Gr. ἀμφί, on both sides, κυρτός, convex) or cissoidal (Gr. κισσός, ivy), biconvex; xystroidal or sistroidal (Gr. ξυστρίς, a tool for scraping), concavo-convex; amphicoelic (Gr. κοίλη, a hollow) or angulus lunularis, biconcave.[19]

Bisecting and trisecting angles

The ancient Greek mathematicians knew how to bisect an angle (divide it into two angles of equal measure) using only a compass and straightedge, but could only trisect certain angles. In 1837 Pierre Wantzel showed that for most angles this construction cannot be performed.

Dot product and generalisations

In the Euclidean space, the angle θ between two Euclidean vectors u and v is related to their dot product and their lengths by the formula

This formula supplies an easy method to find the angle between two planes (or curved surfaces) from their normal vectors and between skew lines from their vector equations.

Inner product

To define angles in an abstract real inner product space, we replace the Euclidean dot product ( · ) by the inner product , i.e.

In a complex inner product space, the expression for the cosine above may give non-real values, so it is replaced with

or, more commonly, using the absolute value, with

The latter definition ignores the direction of the vectors and thus describes the angle between one-dimensional subspaces and spanned by the vectors and correspondingly.

Angles between subspaces

The definition of the angle between one-dimensional subspaces and given by

in a Hilbert space can be extended to subspaces of any finite dimensions. Given two subspaces , with , this leads to a definition of angles called canonical or principal angles between subspaces.

Angles in Riemannian geometry

In Riemannian geometry, the metric tensor is used to define the angle between two tangents. Where U and V are tangent vectors and gij are the components of the metric tensor G,

Hyperbolic angle

A hyperbolic angle is an argument of a hyperbolic function just as the circular angle is the argument of a circular function. The comparison can be visualized as the size of the openings of a hyperbolic sector and a circular sector since the areas of these sectors correspond to the angle magnitudes in each case. Unlike the circular angle, the hyperbolic angle is unbounded. When the circular and hyperbolic functions are viewed as infinite series in their angle argument, the circular ones are just alternating series forms of the hyperbolic functions. This weaving of the two types of angle and function was explained by Leonhard Euler in Introduction to the Analysis of the Infinite.

Angles in geography and astronomy

In geography, the location of any point on the Earth can be identified using a geographic coordinate system. This system specifies the latitude and longitude of any location in terms of angles subtended at the centre of the Earth, using the equator and (usually) the Greenwich meridian as references.

In astronomy, a given point on the celestial sphere (that is, the apparent position of an astronomical object) can be identified using any of several astronomical coordinate systems, where the references vary according to the particular system. Astronomers measure the angular separation of two stars by imagining two lines through the centre of the Earth, each intersecting one of the stars. The angle between those lines can be measured, and is the angular separation between the two stars.

In both geography and astronomy, a sighting direction can be specified in terms of a vertical angle such as altitude /elevation with respect to the horizon as well as the azimuth with respect to north.

Astronomers also measure the apparent size of objects as an angular diameter. For example, the full moon has an angular diameter of approximately 0.5°, when viewed from Earth. One could say, "The Moon's diameter subtends an angle of half a degree." The small-angle formula can be used to convert such an angular measurement into a distance/size ratio.

See also

- Angle bisector

- Angular velocity

- Argument (complex analysis)

- Astrological aspect

- Central angle

- Clock angle problem

- Dihedral angle

- Exterior angle theorem

- Great circle distance

- Inscribed angle

- Irrational angle

- Phase angle

- Protractor

- Solid angle for a concept of angle in three dimensions.

- Spherical angle

- Transcendent angle

- Trisection

- Zenith angle

Notes

- ↑ This approach requires however an additional proof that the measure of the angle does not change with changing radius r, in addition to the issue of "measurement units chosen." A smoother approach is to measure the angle by the length of the corresponding unit circle arc. Here "unit" can be chosen to be dimensionless in the sense that it is the real number 1 associated with the unit segment on the real line. See R. Dimitric for instance.[15]

- ↑ Sidorov 2001

- ↑ Slocum 2007

- ↑ Chisholm 1911; Heiberg 1908, pp. 177–178

- ↑ http://www.mathwords.com/r/reference_angle.htm

- ↑ Wong & Wong 2009, pp. 161–163

- ↑ Euclid (c. 300 BC). The Elements. Check date values in:

|date=(help) Proposition I:13. - 1 2 Shute, Shirk & Porter 1960, pp. 25-27.

- ↑ Jacobs 1974, p. 255.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911

- ↑ Jacobs 1974, p. 97.

- ↑ Henderson & Taimina 2005, p. 104.

- 1 2 3 Johnson, Roger A. Advanced Euclidean Geometry, Dover Publications, 2007.

- ↑ D. Zwillinger, ed. (1995), CRC Standard Mathematical Tables and Formulae, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, p. 270 as cited in Weisstein, Eric W. "Exterior Angle". MathWorld.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911

- ↑ R. Dimitric: On angles and angle measurements

- ↑ J.H. Jeans (1947), The Growth of Physical Science, p.7; Francis Dominic Murnaghan (1946), Analytic Geometry, p.2

- ↑ ooPIC Programmer's Guide (archived) www.oopic.com

- ↑ Angles, integers, and modulo arithmetic Shawn Hargreaves blogs.msdn.com

- ↑ Chisholm 1911; Heiberg 1908, p. 178

References

- Henderson, David W.; Taimina, Daina (2005), Experiencing Geometry / Euclidean and Non-Euclidean with History (3rd ed.), Pearson Prentice Hall, p. 104, ISBN 9780131437487

- Heiberg, Johan Ludvig (1908), Heath, T. L., ed., Euclid, The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements, 1, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sidorov, L.A. (2001) [1994], "Angle", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Jacobs, Harold R. (1974), Geometry, W.H. Freeman, pp. 97, 255, ISBN 0-7167-0456-0

- Slocum, Jonathan (2007), Preliminary Indo-European lexicon — Pokorny PIE data, University of Texas research department: linguistics research center, retrieved 2 Feb 2010

- Shute, William G.; Shirk, William W.; Porter, George F. (1960), Plane and Solid Geometry, American Book Company, pp. 25–27

- Wong, Tak-wah; Wong, Ming-sim (2009), "Angles in Intersecting and Parallel Lines", New Century Mathematics, 1B (1 ed.), Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, pp. 161–163, ISBN 978-0-19-800177-5

Attribution

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), "Angle", Encyclopædia Britannica, 2 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 14

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), "Angle", Encyclopædia Britannica, 2 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 14

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Angles (geometry). |

-

"Angle", Encyclopædia Britannica, 2 (9th ed.), 1878, p. 29–30

"Angle", Encyclopædia Britannica, 2 (9th ed.), 1878, p. 29–30 - Proximity construction of an angle in decimal degrees with the third intercept theorem

- Angle Bisectors in a Quadrilateral at cut-the-knot

- Constructing a triangle from its angle bisectors at cut-the-knot

- Various angle constructions with compass and straightedge

- Complementary Angles animated demonstration. With interactive applet

- Supplementary Angles animated demonstration. With interactive applet

- Angle definition pages with interactive applets that are also useful in a classroom setting. Math Open Reference

- Construction of an angle Site geometry