Bearing (navigation)

In navigation bearing may refer, depending on the context, to any of: (A) the direction or course of motion itself; (B) the direction of a distant object relative to the current course (or the "change" in course that would be needed to get to that distant object); or (C), the angle away from North of a distant point as observed at the current point.

Absolute bearing refers to the angle between the magnetic North (magnetic bearing) or true North (true bearing) and an object. For example, an object to the East would have an absolute bearing of 90 degrees. Relative bearing refers to the angle between the craft's forward direction, and the location of another object. For example, an object relative bearing of 0 degrees would be dead ahead; an object relative bearing 180 degrees would be behind.[1] Bearings can be measured in mils or degrees.

Some specific usages

US Army definition

The US Army defines the bearing from Point A to Point B as the angle between a ray in the direction of north or south, whose origin is Point A, and Ray AB, the ray whose origin is Point A and which contains Point B. The bearing consists of 2 characters and 1 number: first, the character is either N or S. Next is the angle value. Third, the character representing the direction of the angle away from the reference ray - thus, either E, or W. The angle value will always be less than 90 degrees.[2] For example, if Point B is located exactly southeast of Point A, the bearing from Point A to Point B is S 45° E.[3]

The US Army defines the azimuth between Point A and Point B as the angle, measured in the clockwise direction, between the north reference ray and Ray AB. For example, if the bearing between Point A and Point B is S 45° E, the azimuth between Point A and Point B is 135°.[2][3] The angle value in a bearing can be specified in the units of degrees, mils, or grad. An azimuth is specified in the same angle units.[2]

General examples

Piloting

A bearing can be taken on another vessel to aid piloting. If the two vessels are traveling toward each other and the relative bearing remains the same over time, there is likelihood of collision and action needs to be taken by one or both vessels to prevent this from happening.

Warfare

A bearing can be taken to a fixed or moving object in order to target it with gunfire or missiles. This is mainly used by ground troops when using an air-strike on the target.

Search and rescue

A bearing can be taken to a person or vessel in distress in order to go to their aid or, when that is not possible, to report the person or vessel to authorities or someone who can go to their aid.

Other terminology sometimes used

Types of bearings include:

- compass bearings

- grid bearings

- magnetic bearings

- relative bearings

- true bearings

A true bearing is measured in relation to the fixed horizontal reference plane of true north, that is, using the direction toward the geographic north pole as a reference point, while a magnetic bearing is measured in relation to magnetic north, that is in relation to the north direction of the Earth's magnetic field lines at the given location. The latter is not the same as the direction toward the magnetic north pole due to magnetic anomalies.

A grid bearing is measured in relation to the fixed horizontal reference plane of grid north, that is, using the direction northwards along the grid lines of the map projection as a reference point, while a compass bearing, as in vehicle or marine navigation, is measured in relation to the magnetic compass of the navigator's vehicle or vessel (if aboard ship). It should be very close to the magnetic bearing. The difference between a magnetic bearing and a compass bearing is the deviation caused to the compass by ferrous metals and local magnetic fields generated by any variety of vehicle or shipboard sources (steel vehicle bodies/frames or vessel hulls, ignition systems, etc.)

A relative bearing is one in which the reference direction is straight ahead, where the bearing is measured relative to the direction the navigator is facing (on land) or in relation to the vessel's bow (aboard ship).

Bearing measurement

There are several methods used to measure navigation bearings:

- In land navigation, a bearing is ordinarily calculated in a clockwise direction starting from a reference direction of 0° and increasing to 359.9 degrees.[4] Measured in this way, a bearing is referred to as an azimuth by the US Army but not by armies in other English speaking nations, which use the term bearing.[5] If the reference direction is north (either true north, magnetic north, or grid north), the bearing is termed an absolute bearing. In a contemporary land navigation context, true, magnetic, and grid bearings are always measured in this way, with true north, magnetic north, or grid north being 0° in a 360-degree system.[4]

- In aircraft navigation, an angle is normally measured from the aircraft's track or heading, in a clockwise direction. If the aircraft encounters a target that is not ahead of the aircraft and not on an identical track, then the angular bearing to that target is called a relative bearing.

- In marine navigation, starboard bearings are 'green' and port bearings are 'red'. Thus, in ship navigation, a target directly off the starboard side would be 'Green090' or 'G090'.[6] This method is only used for a relative bearing. A navigator on watch does not always have a corrected compass available with which to give an accurate bearing. If available, the bearing might not be numerate. Therefore, every forty-five degrees of direction from north on the compass was divided into four 'points'. Thus, 32 points of 11.25° each makes a circle of 360°. An object at 022.5° relative would be 'two points off the starboard bow', an object at 101.25° relative would be 'one point abaft the starboard beam' and an object at 213.75° relative would be 'three points on the port quarter'. This method is only used for a relative bearing.

- An informal method of measuring a relative bearing is by using the 'clock method'. In this method, the direction a vessel, aircraft or object is measured as if a clock face is laid over the vessel or aircraft, with the number twelve pointing forward. Something straight ahead is at 'twelve o'clock', while something directly off to the right is at 'three o'clock'. This method is only used for a relative bearing.

- In land surveying, a bearing is the clockwise or counterclockwise angle between north or south and a direction. For example, bearings are recorded as N57°E, S51°E, S21°W, N87°W, or N15°W. In surveying, bearings can be referenced to true north, magnetic north, grid north (the Y axis of a map projection), or a previous map, which is often a historical magnetic north.

Usage

If navigating by gyrocompass, the reference direction is true north, in which case the terms true bearing and geodetic bearing are used. In stellar navigation, the reference direction is that of the North Star, Polaris. Generalizing this to two angular dimensions, a bearing is the combination of antenna azimuth and elevation required to point (aim) an antenna in a given direction. The bearing for geostationary satellites is constant. The bearing for polar-orbiting satellites varies continuously.

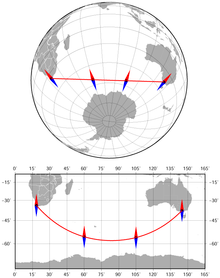

Moving from A to B along a great circle can be considered as always going in the same direction (the direction of B), but not in the sense of keeping the same bearing, which applies when following a rhumb line. Accordingly, the direction at A of B, expressed as a bearing, is not in general the opposite of the direction at B of A (when traveling on the great circle formed by A and B). For example, assume A and B in the northern hemisphere have the same latitude, and at A the direction to B is eastnortheast. Then going from A to B, one arrives at B with the direction eastsoutheast, and conversely, the direction at B of A is westnorthwest.

Bearings can also be transmitted in to NNE-North North East NNNE-North North North east and ENNE-East North North East.

See also

- Absolute bearing

- Relative bearing

- Cardinal direction

- Course (navigation)

- Flight dynamics (fixed-wing aircraft)

- Ground track

- Hand compass

Notes

- ↑ Rutstrum, Carl, The Wilderness Route Finder, University of Minnesota Press (2000), ISBN 0-8166-3661-3, p. 194

- 1 2 3 U.S. Army, Advanced Map and Aerial Photograph Reading, Headquarters, War Department, Washington, D.C. (17 September 1941), pp. 24-25

- 1 2 U.S. Army, Map Reading and Land Navigation, FM 21-26, Headquarters, Dept. of the Army, Washington, D.C. (28 March 1956), ch. 3, pp. 69-70

- 1 2 Keay, pp. 133-134

- ↑ U.S. Army, Map Reading and Land Navigation, FM 21-26, Headquarters, Dept. of the Army, Washington, D.C. (7 May 1993), ch. 6, p. 2

- ↑ This method is used by the Royal Navy and the Royal Australian Navy in accordance with the Admiralty Manual of Navigation, BR45.

References

- Keay, Waly, Land Navigation: Routefinding with Map & Compass, Coventry, UK: Clifford Press Ltd. (1995), ISBN 0-319-00845-2, ISBN 978-0-319-00845-4

- Rutstrum, Carl, The Wilderness Route Finder, University of Minnesota Press (2000), ISBN 0-8166-3661-3

- U.S. Army, Advanced Map and Aerial Photograph Reading, Headquarters, War Department, Washington, D.C. (17 September 1941)

- U.S. Army, Map Reading and Land Navigation, FM 21-26, Headquarters, Dept. of the Army, Washington, D.C. (28 March 1956)

- U.S. Army, Map Reading and Land Navigation, FM 21-26, Headquarters, Dept. of the Army, Washington, D.C. (7 May 1993)

External links

- Webpage with program to calculate Distance & Bearing

- Calculate distance and bearing between two Latitude/Longitude points and much more

- See the end point on a map when you specify a start point, a bearing and a distance.

- More understandable definitions from an online classroom