Company A, 6th Florida Infantry Regiment

| Company A, 6th Florida Infantry Regiment | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Regimental Colors (from ca. March/April 1864 to December 16th, 1864) | |

| Active | March 12, 1862 – April 26, 1865 |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type | Company |

| Role | Infantry |

| Size | 109 aggregate (April, 1862) |

| Part of |

Department of East Tennessee Confederate Army of Kentucky Army of Tennessee |

| Nickname(s) | Davidson's Company; Florida Guards |

| Equipment |

.577 Pattern 1853 Enfield .69 Springfield Model 1842 |

| Engagements |

|

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Captain R. H. M. Davidson: March 12, 1862 - November 16, 1863 |

Company A, 6th Florida Infantry Regiment was a military company of the Confederate States of America during the US Civil War.

On February 2, 1862, the Confederate War Department issued a call for troops. Florida, under this newly imposed quota, would furnish two regiments and a battalion to fight for the duration of the war. The troops would rendezvous at preselected locations and there "be clothed, supplied, and armed at the expense of the Confederate States." Each enlistee would also receive a $50 bounty for volunteering.[1]

Organization

Robert Hamilton McWhorta Davidson of Gadsden County, Florida, was a state senator in 1862. He retired from this position early in 1862 to raise a company of infantry from his home county. A number of men that would serve in Company A had already obligated for 12 months of state service with either Captain R. M. Scarborough’s Company (the “Dixie Blues”) or Captain Wilk Call’s Company (the “Concordia Infantry”). The “Dixie Blues” were taken into state service in 1861. There is no record of how long or where they served; its existence is believed to have been short-lived. The “Concordia Infantry” was mustered into the service of the State by Francis L. Dancy Adjutant and Inspector General, for the term of twelve months, from the 4th day of September 1861, unless sooner discharged. As was the case with the “Dixie Blues”, its service was brief. All told, 7 men from each company would re-enlist for “3 years or the war” with R. H. M. Davidson’s Company in March 1862. Davidson’s recruiting efforts began the first week of March, 1862 at Quincy in Gadsden County, Florida, with the majority of enlistments being accomplished by the 3rd week of March.[2][3][4]

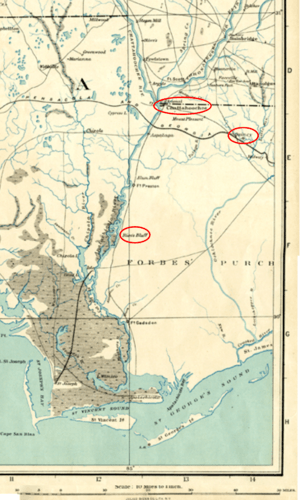

Concurrently, the coastal artillery batteries located at Apalachicola were being moved farther inland in response to exchanges between Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin, General Robert E. Lee, Governor John Milton, and Brigadier General J. H. Trapier, commanding the Department of East and Middle Florida. On March 19, 1862, General Trapier reported that the original plan to establish a battery at Fort Gadsden had been overcome by events, and been landed further up the Apalachicola River at Rico’s Bluff, some 40 miles south of Chattahoochee on the east bank of the Apalachicola River. By order of Brigadier General Trapier, Davidson’s Company along with the company of Captain S. B. Love (later Company B, 6th Florida Infantry) arrived at Rico’s Bluff about March 20 to reinforce and support the newly erected batteries; these two companies would remain at Rico’s Bluff until the regiment left the state.[1][5]

On April 10, 1862, Governor Milton informed Secretary of War George W. Randolph that the requisition for "two regiments and a half of infantry…would by the 15th instant be fully organized and subject to your orders, and companies enough have volunteered for service for three years or the war to compose three full regiments of infantry. ... to serve during the war and wherever their services may be necessary…the Sixth Regiment, at the Mount Vernon Arsenal on the Chattahoochie, will be organized on the 14th instant."[1]

About April 15, elections of field and staff officers for the 6th Florida Regiment were held, with Captain Jesse J. Finley of Company D elected to Colonel, Captain Alexander D. McLean of Company H elected to Lieutenant Colonel, and 1st Sergeant Daniel Lafayette Kenan of Company A elected to Major. The commissions became official on April 18; with the election of field officers concluded, the 8 companies at Mount Vernon Arsenal at Chattahoochee and the 2 companies at Rico's Bluff would be formally organized as the 6th Regiment of Florida Infantry.[5][6] "Davidson’s Company" would be officially designated as Company A; the men of Company A would bestow upon themselves the unofficial sobriquet of "Florida Guards".[7]

On April 23, 1862, Florida Adjutant and Inspector General Wm. H. Milton would inform Governor Milton that, "The following companies compose the Sixth Regiment, eight companies of which are at the Mount Vernon Arsenal and two at Rico’s Bluff; Magnolia State Guards, Capt. L. M. Attaway; Campbellton Greys, Capt. H. B. Grace; Jackson County Volunteers, Lieut. John B. Hayes; Jackson County Company, Capt. H. O. Bassset; Union Rebels, Capt. A. D. McLean; Choctawhatchie Volunteers, H. K. Hagan; Florida Guards, R. H. M. Davidson; Gadsden Greys, Capt. Samuel B. Love; Gulf State Infantry, Capt. James C. Evans; Washington County Company, Capt. A. McMillan, of which regiment J. J. Finley is colonel A. D. McLean lieutenant-colonel, and D. L. Kenan major."[1]

Colonel Finley was somewhat less enthusiastic concerning the organization of the 6th Florida than were Governor Milton and his Inspector General; he noted in his Regimental Return for April that, “…the names of absent officers for that month, the no. and date of order, the reasons for and commencement of absence and period assigned for the same were not reported by the companies of the Regiment. It was not until about the 20th April when or about that time the field officers were commissioned that any company report were made note. Captain Love’s and Captain Davdison’s Companies were stationed at Ricoe’s Bluff on the Apalachicola River about the 20th of March last by order of General Napier the commanding the Military Department of East and Middle Florida with the consent of the Governor… I have been compelled to make up the monthly regimental report from the morning report of companies on the 30th day of April.” His accountability issue with personnel would continue into May; he noted on his Regimental Return for that month, “Owing to the amt of sickness at this Post and the number of men on sick furlough the names of the absentees cannot be given in this Return. The Returns of Captains Evans, Love, and Davidson’s companies have been erroneously included in the Monthly Return of the 6th Florida Battalion commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Chas. [Charles] F. Hopkins.”[5]

Active Service

The 6th Florida Infantry Regiment departed the Mount Vernon Arsenal at Chattahoochee, Florida on June 13, 1862. It would serve from June through August 1862 in the Army of East Tennessee commanded by Major General Edmund Kirby Smith. The Army of East Tennessee was redesignated as the Confederate Army of Kentucky on August 25, 1862, when General Smith led it into eastern Kentucky during the Confederate Heartland Offensive. On November 20, 1862, the Army of Mississippi, General Braxton Bragg commanding, and the Army of Kentucky, General E. Kirby Smith commanding, became the Army of Tennessee. General Bragg assumed command, and General Smith was reassigned to the Department of East Tennessee. The 6th Florida would remain assigned to the Army of Tennessee for the remainder of the war (under General Braxton Bragg through December 27, 1863; under General Joseph E. Johnston from December 27, 1863 to July 18, 1864; under General John B. Hood from July 18, 1864 through January 23, 1865; under Major General Richard Taylor from January 23 to February 23, 1865: and again under General Joseph E. Johnston from February 23 to April 26, 1865.[1][6][8]

Surrender

From April 8 to the 10th, General Johnston reorganized the army, consolidating dozens of shrunken regiments and brigades. Containing fewer soldiers than an understrength battalion, the remnants of the Florida Brigade were united to form the 1st Florida Infantry Regiment, Consolidated - 1st Florida Infantry & 3rd Florida Infantry (consolidated)(Capt. A. B. McLeod); 1st Florida Cavalry (dismounted) and 4th Florida Infantry (consolidated) (Capt George B. Langford); 6th Florida Infantry (Lieut. Malcolm Nicholson); 7th Florida Infantry (Capt. Robert B. Smith). Company A of the original 6th Florida Infantry, along with companies B, C, and D, would be consolidated to form Company D of the 1st Consolidated Regiment of Florida Infantry.[1][5][9] On April 18, General Joseph E. Johnston signed an armistice with General William T. Sherman at Bennett’s Place near Durham, and on April 26, formally surrendered his army. Of the 100-plus men[3] who mustered into Confederate service with "Davidson's Company", only 17 were present. On May 1, 1865, five days after General Johnston surrendered the force under his command, the troops of the 1st Florida Infantry, Consolidated, were paroled.[6][10][11]

Roster

Officers

- Captain Robert Hamilton McWhorta Davidson was born September 23, 1832 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He attended the common schools and the Quincy Academy at Quincy, Florida; then studied law at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville, Virginia. He was admitted to the bar in 1853 and commenced to practice law in Quincy, Florida. He was a member of the Florida House of Representatives from 1856–57 and again from 1858-59. In 1860, he was living at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was a lawyer by profession, owning real estate in the value of $700, and a personal worth of $6,000. He married Leila A. Callis from Virginia on January 9, 1860 at Gadsden County, Florida. Davidson was elected to the Florida State Senate and served from 1860–62, retiring in the latter year to raise a company of infantry. He was enlisted into Confederate service on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida and appointed to the rank of Captain. He was assigned to support a battery of artillery overlooking the Apalachicola River at Rico’s Bluff, Liberty County, Florida; his recruiting efforts caused him to travel numerous times between Rico’s Bluff and Quincy. His company would be absent on duty at Rico’s Bluff when the 6th Regiment was mustered into Confederate service at Chattahoochee in mid-April. Captain Davidson was present with his company when it left the state, and remained with them until February 9, 1863, when he was detached for service to Knoxville, Tennessee as a member of an Examining Board.[12][13] He returned to the company about July 9, 1863. All Florida infantry regiments were brigaded together by General Braxton Bragg on November 12, 1863; Colonel Jesse J. Finley commanding the 6th Regiment would be elevated to command the Florida Brigade with the rank of Brigadier General, Lieutenant Colonel Angus D. McLean would be promoted to Colonel and succeed him in command of the 6th Florida. Major Daniel L. Kenan would be elevated to Lieutenant Colonel, and Captain Davidson would be elevated to Major on November 16, 1863 and serve on the Field and Staff of the 6th Florida Regiment. Davidson’s relief for command of Company A would be 1st Lieutenant Charles Edward Living Allison who was promoted to Captain. Davidson took ill shortly after the Battle of Missionary Ridge and was absent from his new assignment from November 23, 1863 until about January, 1864. He was present with the regiment from his return in January 1864 until the Battle of Dallas, Georgia on May 28, 1864. Just prior to an assault against prepared works occupied by the 37th and 53rd Ohio Infantry, a Federal skirmisher killed Colonel Angus McLean; Lieutenant Colonel Kenan would lead the 6th in the assault, with Major Davidson assuming Colonel Kenan’s position. During the assault, Davidson was wounded. The wound "mangled" a foot, and was so severe that he was furloughed the same day. Due to his injury he was unable to return to the front but was appointed to Lieutenant Colonel and was stationed in Quincy, Florida until the end of the war. He was paroled May 16, 1865 at Tallahassee, Leon County, Florida. After the war, he resumed his law practice. He was a member of the Florida State Constitutional Convention in 1865; a presidential elector on the Greeley and Brown ticket in 1872; and in 1876 had the distinction of being the first democratic congressman elected in Florida after the war, representing 1st district of Florida to the Forty-fifth Congress and to the next six succeeding Congresses (March 4, 1877 – March 3, 1891); chairman, Committee on Railways and Canals (Forty-eighth through Fiftieth Congresses); unsuccessful candidate for re-nomination in 1890 to the Fifty-second Congress. After his term, he was member of the Florida State Railroad Commission, (1897–98) and continued to practice law. For years he was an Elder in the Presbyterian Church. Lieutenant Colonel Davidson, age 75, died January 18, 1908 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He is interred at Western Cemetery, Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida.[3][4][5][14][15]

- 1st Lieutenant Charles Edward Livingston Allison was born March 12, 1837 at Apalachicola, Franklin County Florida. He was the son of Abraham Kyrkyndal Allison (1810-1893), the sixth Governor of Florida (served 1 Apr. 1865-19 May 1865), and his first wife, Mary Jane Nathans (1820-1850). He was a freshman enrolled in South Carolina College in 1855, and then attended the University of Virginia in session 33 (1856-1857). In 1860, he was living at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was a lawyer and newspaper editor by profession, with a personal worth of $4,000. He was enlisted into Confederate service on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida and appointed to 1st Lieutenant. He was present with the company until February 9, 1863, when he was detached for recruiting service in Florida. He also was on detached service as the Officer of City Police at Knoxville, Tennessee, beginning on April 11, 1863. He returned to the company on April 30 and remained with it until he was wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga on September 19, 1863. In that battle, he suffered a gunshot wound to the right arm, which was subsequently amputated at a hospital at Marietta, Georgia. He was promoted to Captain on November 16, 1863 while still in the hospital. He is last recorded as still absent at the hospital as of February 1864; he was paroled May 10, 1865 at Tallahassee, Leon County, Florida. After the war, he established and edited a newspaper in his hometown of Quincy, FL, which he called the "Quincy Commonwealth", and developed his practice as an attorney. By 1870, the U.S. Census lists him as a “lawyer & editor.” In 1885, the Florida State Census gives his profession as “Supt. of Schools.” Allison was also instrumental in the development of the Ladies’ Confederate Memorial Association in Quincy, and was described by one lady as “always interested and one of the foremost in every work and celebration.” Captain Allison applied for and was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. He died on May 7, 1916 at Sevier County, Arkansas.[3][4][5][14][15][16][17]

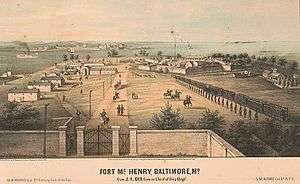

- 2nd Lieutenant Anderson Mills Harris was born June 14, 1827 at Yorkville, South Carolina. In 1860, he was living at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was a clerk by profession, owning real estate in the value of $400, and a personal worth of $10,000. He was enlisted into Confederate service on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida and appointed as 2nd Lieutenant. He was stationed at Rico’s Bluff, and was detailed to remain with the sick when the regiment left the state, and to rejoin the regiment when they were well enough to travel. He rejoined the regiment about June 30, 1862, but became ill and was left behind at Frankfort, Kentucky, in early October. He was captured by Federal forces at Frankfort on October 15, 1862 and transported to the military prison at Fort McHenry, Baltimore, Maryland and paroled from there in November 1862. He arrived in Richmond, Virginia about December 5, 1862, and was given a medical furlough of 30 days by a Doctor Peebles. He returned to the company about February 9, 1863 and remained with it until April 20, 1863 when he was detached for service as Acting Assistant Inspector General to Colonel Robert C. Trigg’s brigade. He would serve in this role until November 15, 1863 when he was appointed AAIG with the rank of 1st Lieutenant by Brigadier General Finley, who was in command of the newly formed Florida Brigade. He remained with the brigade until granted a furlough of 30 days while at Tupelo, Mississippi on January 23, 1865. On March 10, he was documented as a Captain and AAG, and sent to Richmond. He was with what remained of the Florida Brigade when it surrendered at Durham Station, North Carolina on April 26, 1865. He was paroled at Catawba Bridge, South Carolina on May 5, 1865. After the war, he was employed as a lumber inspector. Lieutenant Harris died on November 26, 1881 at Apalachicola, Florida and is interred at Chestnut Cemetery, Apalachicola, Franklin County, Florida.[3][4][5][14][15][18]

- 3rd Lieutenant Hugh Black was born in Gadsden County, Florida on June 28, 1835 as the son of James Black. He served in the Everglades in the third Seminole War (1855–58) as a Sergeant with Captain Parkhill’s Company of Florida Mounted Volunteers from 29 July 1857 to 29 January 1858. He was then described as being 6’ tall, dark complexion, blue eyes, dark hair, and by occupation a farmer. Hugh married Mary Ann Harvey of Leon County in 1860. They moved to Liberty County and he became the tax assessor there. He is also identified as a farmer, owning real estate in the value of $1,000, and a personal worth of $675. Hugh enlisted for state service on September 4, 1861 with Captain Wilk Call’s Concordia Infantry, and appointed 1st Lieutenant. He reenlisted into Confederate service on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida and appointed as 3rd Lieutenant. He was stationed at Rico’s Bluff and was with the company from its departure from Florida until July 8, 1863 when he served as a member of a Regimental Court Martial. He returned to the company at the conclusion of that duty, and was present with it until he was wounded in the right elbow and hand at Chickamauga, Georgia on September 19, 1863. He was hospitalized at Columbus, Georgia shortly thereafter. Despite his wounding and hospitalization, he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant on November 5, 1863. He received a furlough to Florida on December 25, 1863 for 30 days. He returned to the company sometime after February 1864. He became ill in August, 1864. He retired October 19, 1864, and was assigned to Reserve Forces Florida by S.O. 250 dated October 21, 1864. He surrendered at Tallahassee, Leon County, Florida on May 10, 1865. After the war, he lived at Fort Braden and was Clerk of the State Legislature, a Leon County Commissioner, and a Leon County School teacher. Lieutenant Black applied for and was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. He died on May 18, 1916 and is interred at Fort Braden Cemetery, Tallahassee, Leon County, Florida.[3][4][5][6][14][15][19]

Non-commissioned Officers

_Kenan%2C_ca._1851.png)

_ca._1874.png)

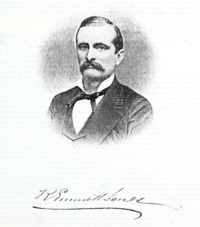

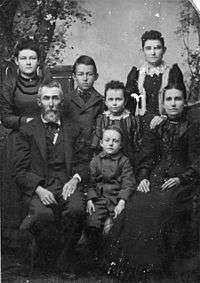

- 1st Sergeant[20] Daniel Lafayette Kenan was born at Kenansville, Duplin County, North Carolina on March 25, 1825. His family moved from there to Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida in 1831. His father died in 1840 when he was still a minor. He married Martha Ann Gregory of Quincy, Florida on February 26, 1851 at Quincy. He was a carriage maker; he also became wealthy by an inheritance of 75 acres of land and 30 slaves from his Aunt, Jane Hall, in 1858. He served in the Florida House of the State Legislature from 1850 until 1859. In 1860 he, along with wife Martha and 6 children, was living at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was a mechanic by profession, owning real estate in the value of $3,000, and a personal worth of $25,000. Kenan was enlisted into Confederate service on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida and appointed as 1st Sergeant. He was stationed at Rico’s Bluff and was with the company until about April 15, when elections of field and staff officers for the 6th Florida Infantry Regiment were held. 1st Sergeant Kenan was elected to Major of the regiment. With his commission becoming official on April 18; Major Kenan would be replaced by 2nd Sergeant Edward B. White as the company’s 1st Sergeant.

ca. January, 1863 - Strawberry Plains, Tennessee - "Our Major is a fine man, the rest are not fit to tote guts to a bear…The first and seventh regiment is in the same fix that the sixth regiment is, their field officers are of no account." - 1st Lieutenant James Hays, Company D, 6th Florida Infantry Regiment.[6]

On November 12, 1863 General Braxton Bragg ordered all Florida infantry regiments into a single brigade. Colonel Jesse J. Finley, commanding the 6th Regiment, would be elevated to command the Florida Brigade with the rank of Brigadier General. Lieutenant Colonel Angus D. McLean would be promoted to Colonel and succeeded him in command of the 6th Florida. Major Kenan was elevated to Lieutenant Colonel on November 16, 1863. When Colonel McLean was killed at Dallas, Georgia on May 28, 1864, Lieutenant Colonel Kenan immediately assumed command of the 6th Florida, and would twice command the Florida Brigade temporarily in General Finley’s stead. The second instance occurred at the Battle of Jonesboro, Georgia on August 31, 1864, where he stepped up after General Finley was wounded in the thick of battle, only to be wounded himself with the loss of two fingers of his left hand to a minié ball. He would suffer a serious wound to his right leg at the Battle of Bentonville, North Carolina on March 19, 1865. He was admitted to C.S.A. General Hospital No. 3 at Greensboro, North Carolina in early April, then transferred to C.S.A. General Hospital No. 11 at Charlotte, North Carolina. His right leg was amputated on April 28, 1865; after recovering, he was paroled on May 7, 1865. Martha Ann died on June 1st, 1871; he remarried to Virginia Douglas Nathans at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida on October 10, 1872. Colonel Kenan was impoverished as a result of the war; the majority of his antebellum wealth was in slaves. Although crippled by his wounds, he served as Gadsden County tax assessor until his death at age 58 on February 12, 1884. He was interred with Masonic honors in an unmarked grave at Western Cemetery, Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida.[3][4][5][6][14][15][21]

- 3rd Sergeant[22] Henry F. Horne was born in Georgia on December 23, 1835. In 1860 he resided near Jasper, Hamilton County, Florida with his parents and two younger brothers. He was a blacksmith, owning real estate in the value of $120. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 13, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida and appointed as 3rd Sergeant. Sergeant Horne was present with his company until June 12, 1862, when he was transferred to the regimental band just prior to the regiment leaving the state. On July 1, he was reassigned to serve as a quartermaster clerk, in which capacity he served until September 6, 1862. He was left sick at Lexington, Kentucky in October, and barely escaped capture. He returned to and remained with the company until January 11, 1863 when he was detached for service at Knoxville, Tennessee as Clerk to the Examining Board. He continued as a Clerk in service to both the Examining Board at Knoxville and to a Colonel Blake until about August 22, 1863 when he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant and assigned to Company G of the 1st Florida Cavalry.

"How he (Horne) manages to do nothing when everyone else is hard at work is a mystery to me." - Lieutenant Colonel William T. Stockton, 1st Florida Cavalry[4]

He was wounded near Atlanta, Georgia on August 8, 1864 and again at Jonesboro on September 18, 1864. He retired to the Invalid Corps on December 2, 1864 and was paroled at Tallahassee, Leon County, Florida on May 15, 1865. Lieutenant Horne died on December 1, 1883 and is interred at Campbellton Baptist Church Cemetery, Campbellton, Jackson County, Florida.[3][4][5][14][15]

- 4th Sergeant John Poole Jordan was born in Virginia in 1837. In 1860 he, along with wife Sarah Frances (née Gunn) and 3 children, was living near Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was a farmer by profession, owning real estate in the value of $1,000, and a personal worth of $8,000. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida and appointed as 4th Sergeant. On April 20, 1862 he was detailed to the regiment’s Headquarters as Commissary Sergeant. He was reported present from that time until October 22, 1863 when he received a furlough of 20 days due to illness. Sometime between November and December 1863, he was documented as serving as the Regimental Quartermaster for the Florida Brigade. He was with what remained of the Florida Brigade when it surrendered at Durham Station, North Carolina on April 26, 1865 and was paroled at Greensboro, North Carolina on May 1, 1865. He died on June 24th, 1892 and is interred at Eastern Cemetery, Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida.[3][4][5][14][15]

- 5th Sergeant Byardam Garden Pringle was born at Charleston, South Carolina 1823. He is listed among the graduates of the College of Charleston, class of 1834.[23] In 1848, he and a W. Y. Paxton purchased the Charleston newspaper “The Evening News”; Pringle was an acknowledged writer and assumed the paper's editorial responsibilities.[24] In 1849, he was appointed as a Magistrate[25][26] of St. Philips and St. Michaels Parishes. In July 1850, Pringle terminated his short editorial career. His record disappears until January 3, 1861 when the sixty-nine members of Florida's secession convention assembled at the state capital at Tallahassee, where a motion was made for John C Pelot from Alachua County was called to the Chair and B. Garden Pringle of Gadsden County was requested to act as Secretary.[27] He again drops from the record until he enlisted in Davidson’s Company on April 14, 1862 at Chattahoochee, Gadsden County, Florida and appointed as 5th Sergeant. His description was given as 5’ 7” tall, hazel eyes, black hair, and dark skin. On May 1, 1862 he was detailed as Clerk and private secretary to Colonel Jesse J. Finley, commanding the 6th Florida Regiment. He was present until November 15, 1862 when he was awarded a furlough of 40 days; he did not return until about March 9, 1863. On April 6, 1863 he was detailed as a clerk to the Headquarters of the Department of East Tennessee at which he served until June 13, 1863. On that date, he was granted furlough of 30 days, and from which he never returned.[3][4][5]

- 2nd Sergeant Edward Booth White was born on November 23, 1834. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida and was appointed as 2nd Sergeant. He was promoted to 1st Sergeant on April 18, 1862, relieving Daniel Lafayette Kenan as the company’s 1st Sergeant when he was elected to Major during the regiment’s organization. He was present with the company until October 16, 1862 when he was accidental wounded by the discharge of a gun (artillery) at Big Hill, Kentucky. He was left behind to recover from his wounds, and captured on October 29. He was transferred to Lexington, Kentucky on November 15 and subsequently transferred to Louisville, Kentucky on November 17, where he would be place on the steamboat Mary Crane with other confederate prisoners. The trip would take them to Vicksburg, Mississippi via Cairo, Illinois for exchange. He was at that time described as 27 years old, 5’ 7-1/2” tall, with gray eyes, dark hair, and light complexion. The date of his return to the company is unknown, but he was awarded a furlough of 40 days effective from January 14, 1863. He returned to about March 9 of 1863. He suffered a pay stoppage for “ordnance stores lost” between November 1 and December 31, 1863 in the amount of $13.30; this likely due to the Confederate defeat at Missionary Ridge on November 25. He was reported present with the company from this point until it surrendered at Durham Station, North Carolina on April 26, 1865. He was listed with the rank of 2nd Lieutenant, and paroled at Greensboro, North Carolina on May 1, 1865. Lieutenant White died on October 17, 1877 and is interred at City Greenwood Cemetery, Weatherford, Parker County, Texas.[3][4][5][14]

- 3rd Corporal[28]Henry A. Crosby was born in 1839 near Appling, Columbia County, Georgia.[29] He relocated to Gadsden County, Florida sometime after 1850 but before the Federal census of 1860. He was shown living at the dwelling of Todd Hardy, a farmer, and listed as a laborer. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 14, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida and was appointed as 3rd Corporal. He was present with the company until his death from disease while a patient in hospital at Knoxville, Tennessee on July 12, 1862. He was recorded as being interred at the Bethel Confederate Cemetery, Knoxville, Knox County, Tennessee.[3][4][5][14][15]

- 1st Corporal Robert Emmett Jones was born at Baltimore, Baltimore County, Maryland on November 9, 1842. When he was an infant, his parents removed with him to Florida, where he there remained until he attained the age of seventeen years, attending the best schools of Quincy, and becoming thoroughly prepared for a collegiate course. He then entered Wolford College, South Carolina, and graduated with honor. He returned to Quincy, where he began the study of law in the office of Honorable Charles H. Dupont Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of that State. After three years, he was admitted to practice in the various courts of the State, and was actively and successfully engaged when the American civil war began. In 1860 he was living near Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida in the home of his mother, Lucretia, along with five younger brothers and a younger sister. He was listed as being a law student. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 14, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida and was appointed as 1st Corporal. He tendered his resignation from this position May 1, 1862 and was transferred to Company B of the 1st Florida Special Battalion on June 14 in direct exchange for Private C. Peter Muller of that command.[3][4][5][14][15][30]

- 4th Corporal John W. Poindexter was born in Florida ca. 1845. In 1860, he was living in the residence of Harriet L. Poindexter (relationship unknown) and an 8 years old orphan named Lilla Goldwire near Mount Pleasant, Gadsden County, Florida. Harriet was quite well off, owning real estate in the value of $5,000 and a personal wealth of some $14,000. Both John and Lilla attended school within the 12 months preceding the census. John enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 15, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida and was appointed as 4th Corporal. He was present with the company from his enlistment until June 4, 1863; he was promoted to 4th Sergeant on July 14, 1862. He was discharged from service almost a year later on June 4, 1863 by substitution of James Sweeney.[3][4][5][14][15]

- 2nd Corporal John C. Saunders was born ca. 1830 in Georgia. In 1860 he was living near Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida, along with his wife Mary and 4 children. He was by occupation a laborer, with a personal worth of $400. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 15, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida and was appointed as 2nd Corporal. He was detailed to service as a nurse to remain in Florida with the company’s sick when the company left the state. He was promoted to 3rd Sergeant on May 1, 1862, and rejoined the company between June 30 and November 12, 1862. He was present on all rolls until between July 9 and October 31, 1863 when he was reported sick in a hospital at Newnan, Georgia. He was given a furlough of 35 days on November 12, 1863, presumably to return to Florida to convalesce. He died of disease in Florida on January 24, 1864.[3][4][5][14][15]

Enlisted Men

- Musician Alexander Elick McPherson was born at Barbour County, Alabama on March 19, 1847. Sometime prior to 1860, his family moved to Marianna in Jackson County, Florida. In the census of that year, he is shown living at his father Archibald’s residence along with his step-mother Debora Ann (nee Edinfield), an older sister and brother and two younger brothers and two younger sisters. Alexander, older brother James, and father Archibald all enlisted on March 20, 1862 at Chattahoochee, Gadsden County, Florida; Alexander was 15 years old and James was 16 years old. Both were assigned as musicians.[31][32] Archibald, being some 51 years old, was taken into service as a Private. Alexander was present with the company from the date of his enlistment until October 10, 1863 when he was ordered to the hospital by a Surgeon for unspecified reason. He is documented present at the S. P. Moore Hospital at Griffin, Georgia during the period September 30 to December 1, 1863.[33][34] Alexander returned to the company on December 1, 1863 and was reported present from this point until it surrendered at Durham Station, North Carolina on April 26, 1865. He was listed with the rank of Private, and paroled at Greensboro, North Carolina on May 1, 1865. He was twice married; first to Annie Ellen (née Gainer), and subsequently in 1872 to Sarah Elizabeth (née Gregory) with whom he fathered 7 children. Private McPherson applied for and was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. He died on June 16, 1930 at Gretna, Gadsden County, Florida.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Musician James “Jim” McPherson, older brother of Alexander McPherson, was born at Barbour County, Alabama on December 6, 1839. Sometime prior to 1860, his family moved to Marianna in Jackson County, Florida. In the census of that year, he is shown living at his father Archibald’s residence along with his step-mother Debora Ann (nee Edinfield), an older sister, three younger brothers and two younger sisters. James, younger brother Alexander, and father Archibald all enlisted on March 20, 1862 at Chattahoochee, Gadsden County, Florida; James was 16 years old and Alexander was 15 years old. Both were assigned as musicians. In November and December 1863, “Jim” pulled guard duty[35][36] at the city jail at Knoxville, Tennessee on November 17–18; in the same period, he was also detailed as a company cook.[37][38] He suffered a pay stoppage for “ordnance stores lost” between November 1 and December 31, 1863 in the amount of $13.30; this likely due to the Confederate defeat at Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863. Jim was present on all rolls until November 15, 1864; he is documented as an in-patient at the Madison House Hospital at Montgomery, Alabama on November 5, 1864 for unknown ailment. He was reported present with the company from this point until it surrendered at Durham Station, North Carolina on April 26, 1865. He was listed with the rank of Private, and paroled at Greensboro, North Carolina on May 1, 1865. James married Ellen Browning sometime after 1862. He applied for and was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. Private “Jim” McPherson died on June 16, 1930 at Greensboro, Gadsden County, Florida and is interred at the Sunny Dell Cemetery, Gretna, Gadsden County, Florida.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private J. S. Barker died in Kentucky, and was buried in Lexington Cemetery.[3]

- Private Thomas F. Barr was born on June 19, 1844 at Jefferson County, Florida. In 1860 he was living near Jasper, Gadsden County, Florida, at his father John’s residence along with his mother Mary, an older sister, and an infant brother; his occupation was laborer. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on May 5, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was transferred on June 12, 1862 to Captain Gregory’s Company (Company H, 5th Florida Infantry) in direct exchange for Private J. W. Tolen (John R. Tolar) of that command.[4][5][14][15]

- Private Neil Graeme Black, the younger brother of 1st Lieutenant Hugh Black, was born on May 31, 1840 at Gadsden County, Florida. In 1860 he was living near Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida, at his father Neil’s residence along with his mother Sarah, an older brother, two younger sisters and brother. Neil had attended school during the preceding 12 months, along with his younger sisters and brother. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12h, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was present with the company from his enlistment until October 28, 1862 when he was reported sick in the hospital at Knoxville, Tennessee. He was given a furlough of sixty days beginning in November; he was recorded as being absent without leave between the expiration of his furlough and February 9, 1863, when he returned to the company. He was present with the company from that date until November 29, 1863 when he was admitted to the Floyd House and Ocmulgee Hospitals at Macon, Georgia with chronic diarrhea. He returned to the company before January 1, 1864 and was present with what remained of the Florida Brigade when it surrendered at Durham Station, North Carolina on April 26, 1865. He was paroled at Greensboro, North Carolina on May 1, 1865. He married Ann Lott on November 12, 1867. He applied for and was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. Private Black died on April 30, 1911 and is interred at Black Moseley Cemetery, Gadsden County, Florida.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private James Cornelius Boykin was March 9, 1843 at Gadsden County, Florida. In 1860 he was living near Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida, at his father John’s residence along with two older brothers and sisters, and two younger sisters. James had attended school during the preceding 12 months, along an older brother and sister, and his two younger sisters. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12h, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was present with the company from his enlistment until June 20, 1862 when he was reported sick at Atlanta, Georgia. He was reported absent without leave in Florida in muster reports beginning on November 12, 1862 and continuing through March 2, 1863. He apparently returned to the company prior to April 11, 1863; he was assigned to police duty at Knoxville, Tennessee on that date. He was wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga on September 19, 1863, and sent to a hospital at Atlanta Georgia where he remained until October 10, at which time he received a furlough of 30 days. He married Jane Carolina McKeown in 1863; it is not unlikely that the marriage occurred between his return to Quincy and December 31, 1863. He is last recorded as still absent at Quincy, Florida as of February 1864; he surrendered at Tallahassee, Leon County, Florida on May 10, 1865 and was paroled at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida on was paroled May 21, 1865. After the war, he engaged in farming then became a merchant at Chattahoochee, Gadsden County, Florida. He moved to Washington County, Florida in 1876, where he continued his trades and served as Sheriff. Afterward, he moved to Jackson County, Florida, where he worked as a clerk until he passed away on November 26, 1885 at Sneads, Jackson County, Florida. He was a Mason, and is interred at Pope Cemetery, Sneads, Jackson County, Florida.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private Josephus Bracewell was born January 27, 1830 at Houston County, Georgia. Moved to Florida in winter of 1854, and married Amanda Walden on January 28, 1856 at Gadsden County, Florida. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 9, 1862 at Rico’s Bluff, Liberty County, Florida. He was recorded as absent sick at Calhoun County, Florida until June 30, 1862; he returned to the company about June 30 and was present with it until July 7, 1863 when he was detached for service as a teamster to Major J. Glover, Chief Quartermaster of the Department of East Tennessee. Private Bracewell was severely wounded on July 22, 1864 during the Battle of Atlanta, sustaining gunshot wounds to his right shoulder, left arm, and jaw. He returned to Florida to convalesce and was still in Florida at the war’s end; he was paroled at Tallahassee, Leon County, Florida on May 16, 1865. He was at that time described as 5’ 8” tall, light hair and skin, and blue eyes. After the war, he lived at Bristol in Liberty County, Florida. Private Bracewell applied for and was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. He died on January 26, 1916 at Bristol, Liberty County, Florida and is interred at Meacham Cemetery, Bristol, Liberty County, Florida.[3][4][14]

- Private James M. Bryant was born at Gadsden County, Florida ca. 1831. In 1860 he was living in the Tologee District of Gadsden County, Florida with his wife Elizabeth, whom he married within the 12 months preceding the census, and three sons. He was by occupation a carpenter, with a personal worth of $100. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on June 22, 1862 at Chattahoochee, Gadsden County, Florida as a substitute for James H. Gee, also of Gadsden County, Florida. He was present with the company from his enlistment through December 20, 1863, and was promoted to 2nd Corporal between April 30 and July 9, 1863. He was sent to the Atlanta Medical College Hospital at Atlanta, Georgia on December 20, 1863 and died of unspecified illness the following day. He is interred at Oakland Cemetery, Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private Jesse R. Butler was born ca. 1838. He enlisted for state service on September 14, 1861 with Captain Wilk Call’s Concordia Infantry. He reenlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was absent sick at Liberty County, Florida prior to June 30, 1862, but was present with the company after that date until his death from disease on September 30, 1862 in a hospital at Lexington, Kentucky. He is interred at Lexington National Cemetery, Lexington, Fayette County, Kentucky.[3][4][5][14]

- Private John Butler was born on July 6, 1837 at Gadsden County, Florida. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on May 9, 1862 at Liberty County, Florida. He was absent sick at Atlanta, Georgia prior to June 30, 1862, but was present with the company from July 30 until December 22, 1862 when he was detached for service as a teamster at Knoxville, Tennessee. He returned to the company prior to February 9, 1863. He suffered a pay stoppage for “ordnance stores lost” between November 1 and December 31, 1863 in the amount of $55.85; this likely due to the Confederate defeat at Missionary Ridge on November 25. He was reported present with the company from this point until it surrendered at Durham Station, North Carolina on April 26, 1865. He was paroled at Greensboro, North Carolina on May 1, 1865. He married Martha Mobley on February 21, 1867 at Wakulla County, Florida. John was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. He died on April 20, 1910 and is interred at Mount Tabor Cemetery, Lakeland, Polk County, Florida.[3][4][5][14]

- Private John Calvin Campbell was born ca. 1833. In 1860 he was living near Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida, at his father Alex’s residence along with his mother, seven younger brothers and one younger sister. His occupation was as a laborer. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 15, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was appointed 1st Corporal on August 1, 1862. John was with the company from his enlistment until October 16, 1862, when he was mortally wounded by the accidental discharge of a gun at Big Hill, Kentucky. He was left behind at Richmond, Kentucky and died from his wounds on January 1, 1863.[3][4][5][14]

- Private David Cannon was born ca. 1831 in North Carolina. In 1860 he was living near Blue Creek, Liberty County, Florida with wife Mary and four children. He owned real estate valued at $400, and a personal worth of $196. David enlisted in Davidson’s Company on May 4, 1862 at Rico’s Bluff, Liberty County, Florida. He was listed at sick at Liberty County prior to June 30 of 1862, but rejoined the company after that date and was with it until October 28, 1862 when he again took ill and was admitted to the hospital at Knoxville, Tennessee. He returned to the company prior to November 12, and was with it until he was mortally wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga, Georgia about the 19th of September. He was hospitalized at La Grange, Georgia where he died on September 22, 1863. Private Cannon is identified on the Chickamauga Roll of Honor[39] for “conspicuous gallantry and good conduct in battle."[1][3][4][5][14][15]

- Private Jacob C. Cannon was born ca. 1837 in North Carolina. In 1860 he was living near Blue Creek, Liberty County, Florida, at his father Ira’s residence along with his mother, four younger brothers and four younger sisters. He married Mary A. Boykin on January 23, 1862 at Gadsden County, Florida. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on May 8, 1862 at Rico’s Bluff, Liberty County, Florida. His younger brother, Thomas, enlisted in the same company in March. John was listed at sick at Liberty County prior to June 30 of 1862, but rejoined the company after that date and was with it until October 24, 1862 when he again took ill and was admitted to the hospital at Knoxville, Tennessee. He returned to duty prior to November 12, 1862 and was with the company until August 30, 1863 when he was again admitted to a hospital for illness, this time at London, Tennessee. He appears to have returned to the company prior to November 25, 1863, because he suffered a pay stoppage for “ordnance stores lost” between November 1 and December 31, 1863 in the amount of $55.85; this likely due to the Confederate defeat at Missionary Ridge on November 25. He suffered a gunshot wound to the left groin at Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia on June 15, 1864. The wound was of such severity that he would not return to service; he surrendered at Quincy, Gadsden County Florida on May 11, 1865 and was paroled from there eleven days later. Jacob was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. He died on March 29, 1893 and is interred at Providence Baptist Church Cemetery, Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private Thomas H. Cannon was born ca. 1848 in North Carolina. In 1860 he was living near Blue Creek, Liberty County, Florida, at his father Ira’s residence along with his mother; he was the sixth of nine children. He enlisted for state service on September 7, 1861 with Captain Wilk Call’s Concordia Infantry with the rank of private, and reenlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden, Florida. His oldest brother, Jacob, would enlist in the same company in May. Thomas stated his age as 18 at the time of enlistment; the U.S. Census of 1860 put his age at enlistment at 14 years. He was present with the company from enlistment until July 12, 1862 when he was detailed as a wagon guard. We would be detached for service as a wagoneer at Knoxville, Tennessee on December 22, 1862. He returned to the company by February 9, 1863 and was present with it until September 19, 1863 when he was mortally wounded at Chickamauga, Georgia. He died in a field hospital on September 22, 1863.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private William Carroll was born ca. 1841. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden, Florida. He was rejected for service by an inspecting officer on April 19, 1862.[3][4][5][14]

- Private John J. Cowan was born at Pike County, Georgia on March 19, 1821. He came to Florida in October, 1842. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on May 14, 1862 at Rico’s Bluff, Liberty County, Florida. He was present with the company from his enlistment until October 28, 1862 when he was reported sick in the hospital at Knoxville, Tennessee. He returned to the company prior November 12, 1862. He was reported to been on guard duty at Knoxville, Tennessee on August 16–17, and again on August 22nd-23rd, 1863. He was wounded in the left leg at the Battle of Chickamauga, Georgia on September 22, 1863. On October 15, 1863 he was granted a furlough of 60 days at Forsythe, Georgia. He was absent sick in a hospital at Tallahassee, Florida from December 19, 1863 until sometime after February 23, 1864. He did rejoin the company; he was with what remained of the Florida Brigade when it surrendered at Durham Station, North Carolina on April 26, 1865 and was paroled at Greensboro, North Carolina on May 1, 1865. He married Sarah Colvin on October 9, 1878 at Gadsden County, Florida. Private Cowan applied for and was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. He died on February 22, 1912 at Manatee County, Florida. He was interred at the expense of Manatee County; his interment location is unknown.[3][4][5][14]

.jpg)

- Private George W. Crawford was born ca. 1844.[41] He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on April 18, 1862 at Rico’s Bluff, Liberty County, Florida as a substitute for a William King, who had enlisted on March 12. He was present with the company from his enlistment date until October 10, 1862 when he was left sick at Harrodsburg, Kentucky. He was reported as absent without leave in Florida from that time until his return to the company about March 12, 1863. (He was in fact captured at Harrodsburg after Confederate forces withdrew, he is documented as awaiting exchange onboard the steamer “Maria Denning” near Vicksburg, Mississippi on November 15, 1862.) He was present with the company from March 12 through July 9, 1862; sometime between July 9 and October 31, he was reported sick at Atlanta, Georgia and reported absent without leave. He was with the company at the Battle of Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863 and reported as missing in action. He was admitted to [Federal] General Field Hospital at Bridgeport, Alabama on December 10, 1863 due to a gunshot wound in his right arm. He was transferred to [Federal] General Hospital No. 3 at Nashville, Tennessee on December 11, arriving there on the evening of December 12, and sent to the rest home on December 20. He remained there until March 20, 1864 when he was released from the hospital and transferred to the [Federal] Military Prison at Louisville, Kentucky. He was transferred from there to Camp Chase, Ohio on March 24, 1864 arriving there two days later. He was paroled from Camp Chase on February 25, 1865 and transferred to City Point, Virginia for exchange. He arrived at 3rd Division General Hospital Camp Winder, Richmond, Virginia On March 3, 1865. He was transferred to Jackson Hospital, Richmond, Virginia on March 7, 1865 and received a furlough of 30 days.[3][4][5][14]

- Private James T. Crawford was born ca. 1827 in Georgia. In 1860 he was living in the Tologee District of Gadsden County, Florida with his wife Sarah and one daughter. He was by occupation a laborer, with a personal worth of $100. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was reported absent sick at his home, and died there on July 9, 1862.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private Isham J. Crosby was born ca. 1840 in South Carolina. In 1860 he was living near Starke in Alachua County, Florida at the residence of Jackson Reddish and family, who was a farmer of some means. Isham’s occupation was shown as a laborer. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 25, 1862 at Rico’s Bluff, Liberty County, Florida. He was present with the company until being detailed in November, 1862 as an orderly to Colonel Jesse J. Finley, commanding the 6th Florida Infantry Regiment. He was sent for unknown cause, under Surgeon’s orders, to the hospital on October 29, 1863. He returned prior to January 1, 1864. He died of unspecified cause on October 11, 1864, and is interred at Rose Hill Confederate Cemetery, Macon, Bibb County, Georgia.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private William Barnett Davis was born on January 18, 1834 in Alabama. He married Mary Gornto on April 4, 1861. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was present with the company until October 25, 1862 when he was sick in a hospital at Knoxville, Tennessee. After returning to the company, his was detailed as a wagoneer at Knoxville from December 22, 1862 until February 9, 1863. He was with the company from that point until it was surrendered with what remained of the Florida Brigade at Durham Station, North Carolina on April 26, 1865. He was paroled at Greensboro, North Carolina on May 1, 1865. Mary died on July 4th, 1865. He remarried on January 10, 1866 to Cornelia Fletcher. There is no record of Cornelia’s death or divorce; William remarried for the final time to Margaret McDonald. In 1884, William moved to Taylor County, having purchased 340 acres 8 miles southeast of Perry. Two years later, he was operating a small mercantile business in Perry. He died on March 3, 1901 and is interred at Woodlawn Cemetery, Perry, Taylor County, Florida.[3][4][5][14]

- Private Simeon S. Dugger, Sr. was born on September 29, 1829 at Thomas County, Georgia. He married Mary A. Pitman on October 2, 1857 at Gadsden County, Florida. In 1860 he was living in Leon County, Florida with Mary and two daughters. He was by occupation a farmer, with a personal worth of $95. He enlisted April 1, 1864 at Whitfield County, Georgia in Captain Davidson’s Company; however, there is no official record of his service until he was captured near Marietta, Georgia on July 3, 1864 immediately following the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain.[43] He was sent to the Federal Military Prison at Nashville, Tennessee, and immediately sent from there to Louisville Kentucky. On July 13, 1864, he was transferred to Camp Morton, Indianapolis, Indiana arriving there on July 14. While imprisoned at Camp Morton, Private Duggan contracted a severe respiratory infection, resulting in the loss of sight in his right eye. He was paroled on March 15, 1865 and sent via the Baltimore and Ohio railroad to Point Lookout, Maryland to await exchange. Simeon was admitted General Hospital No. 9 at Richmond, Virginia, on March 24, 1865. He surrendered at Tallahassee on May 10, 1865, and was paroled on May 18, 1865. After the war, Private Dugger and his family moved to Liberty County, Florida near Hosford. He applied for and was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. He died on September 18, 1904 at Hosford, and is interred at Blue Creek Cemetery, Liberty County, Florida.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private Elias Joshua Edenfield was born ca. 1842 in Georgia. In 1860, he was living at the residence of James Rowan and family in the Tologee District of Gadsden County, Florida. His profession is given as laborer. In 1861, he enlisted in Captain Rabon Scarborough’s Florida State Militia Company, the “Dixie Blues”. He reenlisted into Confederate service on April 17, 1862 at Chattahoochee, Gadsden County, Florida in Captain Davidson’s Company by Captain Davidson for a period of 3 years. He was present with the company from his enlistment until February 10, 1864 when he was hospitalized under Surgeon’s order at Walker Hospital at Columbus, Georgia. He remained there until rejoining his company on March 30. He was wounded by a shell fragment in left leg at Atlanta on July 22, 1864, and hospitalized on July 27 at the Marshall Hospital at Columbus, Georgia; then transferred to the 1st Mississippi C.S.A. Hospital at Jackson, Mississippi, where he was admitted for “haemorrhagia” (heavy bleeding) on August 20. He returned to the company on September 18, 1864. He surrendered at Tallahassee on May 10, 1865, and was paroled there on May 18, 1865. He returned to Grady County, Georgia and married Anna Kirkland[44] on November 4, 1866. He is recorded to have lived in Mitchell County, Georgia in 1870, but returned to Grady County prior to 1906. He applied for and was awarded a Georgia Confederate Pension. He died after 1907; the actual date of death and place of interment is unknown.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private Darley Eubanks was born ca. 1833 in Georgia. He married Nancy Todd on July 28, 1856 at Gadsden County, Florida. In 1860, he was living near Bristol Creek, Liberty County, Florida with Nancy and an infant daughter. He had a personal worth of $100. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 17, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was listed as sick at Gadsden County from the date of his enlistment, and was there when the company left the state in June. He returned to the company November 12, 1862, and was present with it until late November/early December, 1863. He died of unspecified disease while in a hospital at Griffin, Georgia on December 6, 1863. He is interred at Stonewall Cemetery, Griffin, Spalding County, Georgia.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private William A. Fair was born ca. 1841 in Georgia. In 1860 he was living near Milledgeville, Baldwin County, Georgia, at his father Peter’s residence along with his mother; he was the fourth of seven children, all boys. His profession was harness maker, and he had a personal worth of $25. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. On August 8, 1863 he was transferred to Company A, 3rd Regiment Engineer Troops (CSA), and served as an “Artificer”,[45] attached to General Simon Bolivar Buckner’s Corps.[3][4][5][14][15][46]

.jpg)

- Private William J. Ferrell was born October 7, 1833 at Washington County, Georgia. He married Margaret S. Floyd on January 15, 1857. In 1860 he was living near Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida, along with Margaret and 2 sons. He was by occupation an overseer. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on April 28, 1862 at Rico’s Bluff, Liberty County, Florida. William was promoted to 4th Corporal on June 5, 1863. He was captured near Nashville, Tennessee on December 16, 1864 and sent to the military prison at Camp Douglas, Illinois. He was released on June 19, 1865. Private Ferrell applied for and was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. He died on April 27, 1917 and is interred at Hosford Cemetery, Hosford, Liberty County, Florida.[3][4][14][15]

- Private John J. Fillingin

- Private Joseph C. Fletcher was born in Georgia ca. 1844. In 1860, he was living near Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida, at his father Joseph’s residence along with his mother and eight other children. He was the second of seven Fletcher children; Frances and James Tomberlin, both 11 years of age, also resided at the Fletcher residence. Young Joseph listed his profession as farm laboring; he had attended school with 12 months of the census. In 1861, he enlisted in Captain Rabon Scarborough’s Florida State Militia Company, the “Dixie Blues”. He reenlisted into Confederate service with Davidson’s Company on March 13, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was recorded as absent sick at Calhoun County, Florida until June 30, 1862; he returned to the company about June 30 and was present with it until December 22, 1862. After completion of his detached service, he returned to the company and was present with it until he was again detached for duty, this time to the City Police at Knoxville, Tennessee on April 25, 1863. He was documented on a clothing issue receipt dated September 10, 1864; whether he survived the war, his date of death and place of interment are unknown.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private Henry A. Flowers was born ca. 1842 in Florida. In 1860, he was living in Madison County, Florida, at his father Joseph’s residence. He was the sixth of eight children, and gave his profession as a day laborer. He enlisted for state service on September 4, 1861 with Captain Wilk Call’s Concordia Infantry with the rank of private. He reenlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was recorded as absent sick at Calhoun County, Florida until June 30, 1862; he returned to the company about June 30 and was present with it until December 20, 1862 when he was detached for service as a pork house guard at Knoxville, Tennessee. He was hospitalized while at Knoxville, and succumbed to disease on March 18, 1863. His place of interment is unknown.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private L. Fowler was born ca. 1836 in Alabama. In 1860, he was living near Apalachicola, Franklin County, Florida with his older brother, two younger brothers and a younger sister. He appears on an undated List of Prisoners transferred from Louisville, Kentucky to Vicksburg, Mississippi for exchange, being captured on November 1, 1862.[5][14][15]

- Private Richard Freeman was born ca. 1837. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was present with the company until September 3, 1862 when he was detached for service as a wagoneer. After this assignment, he returned to the company and was present with it until April 11, 1863 when he was assigned to service with the city police at Knoxville, Tennessee. He was again detailed as a wagoneer on June 25, this time in service to the 6th Florida Regiment. He was reported absent sick between June 25 an October 31, 1863, but returned to the company to be assigned extra duty near Chickamauga, Georgia from November 1 through 28th 30th, 1863. He obtained a furlough of 30 days beginning on November 28, but was reported absent without leave before the end of December. He did return to the company in January, but was ordered hospitalized by Surgeon’s Certificate on February 21, 1864. He was again hospitalized on May 23, 1864 at the Ocmulgee Hospital at Macon, Georgia, being afflicted with fistula-in-ano.[47] Private Freeman was transferred to a hospital at Columbus, Georgia on May 28, 1864; he apparently succumbed to his affliction, and was reported interred in a local cemetery.[3][4][5]

- Private Richard C. Gatlin was born January 9, 1845 at Geneva County, Alabama. His family relocated to Gadsden County, Florida ca. 1848. In 1860, Richard was living at the residence of his father, Richard, along with his mother and 10 brothers and sisters. His profession was given as a laborer. He, along with older brothers Thomas and William, enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. Richard was with the company from the time of his enlistment until August 12, 1862 when he was discharged from service for physical disability. He reenlisted in Company L, 1st Florida (Reserves) Regiment at Quincy on April 15, 1864. He was serving as a cooper at Tallahassee, Florida at the close of the war; he surrendered there on May 10, 1865 and took the Oath of Allegiance on May 12. He was described at the time as 5'6" tall, with black hair & eyes, and fair skin. He married Sarah Haygood at Gadsden County on January 20, 1869. Private Gatlin applied for and was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. He died on May 24, 1915 and is interred at Antioch Baptist Church Cemetery at Wetumpka, Gadsden County, Florida.[4][5][14][15]

- Private Thomas Gatlin was born ca. 1844 in Alabama. His family relocated to Gadsden County, Florida ca. 1848. In 1860, William was living at the residence of his father, Richard, along with his mother and 10 brothers and sisters. His profession was given as a laborer. He, along with younger brothers Richard and William, enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. Thomas was present with the company until September 3, 1862 when he was detached for service as a wagoneer. He returned to the company prior to November 12, and was again detached for service on December 20, this time as a pork house guard Knoxville, Tennessee. He continued in this service until about March 12, 1863; he returned to the company and was again detailed for detached service, this time to the city police at Knoxville, Tennessee on April 11. He returned to the company about April 30, was present with it from that time until September 19, 1863 when he was killed in action at the Battle of Chickamauga. His place of interment is unknown.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private William Gatlin was born ca. 1844 in Alabama. His family relocated to Gadsden County, Florida ca. 1848. In 1860, William was living at the residence of his father, Richard, along with his mother and 10 brothers and sisters. His profession was given as a laborer. He, along with older brother Thomas and younger brother Richard, enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. Shortly after his enlistment he was detailed to make barrels, he became attached to “Captain Archibald C. Smith’s Cavalry of Colonel George W. Scott’s Battalion (or regiment) of Florida Troops” [5th Battalion, Florida Cavalry]. He enlisted with this organization on July 27, 1863, and continued with that organization until the end of the war. He surrendered at Tallahassee, Florida on May 10, 1865 and took the Oath of Allegiance on May 12. He was described as 5” tall, with light hair, black eyes, and light complexion. Married Lilla Bassett at Gadsden County, Florida on May 25, 1898. Private Gatlin applied for and was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. He died on October 23, 1913 at Gretna, Gadsden County, Florida. His place of interment is unknown.[3][5][14][15]

- Private George W. Giddings was born ca. 1817 in Georgia. In 1860 he was living near Rico’s Bluff, Liberty County, Florida, along with Sarah and a daughter. He was by occupation a wood chopper. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was left sick at Gadsden County, Florida when his company left the state. He rejoined the company shortly after June 30, 1862, but was again absent sick at Knoxville, Tennessee on October 28, 1862. He was granted a furlough of 5 days, beginning on November 20; he was reported as absent without leave in Florida from November 25, 1862 through March 21, 1863. He was listed as sick in a hospital at Columbus Georgia from March 21, 1863 through July 9, 1863; he apparently returned to the company prior to August 22, as he was detailed on guard duty at the jail iat Knoxville, Tennessee from August 22 until August 23, 1863. He was ordered into the hospital under Surgeon’s order on October 26, 1863. He is believed to have returned to the company, but was again ordered by the Surgeon into the hospital near Dalton, Georgia on February 4, 1864. He was diagnosed with scrofula[48] and general debility,[49] and discharged from service at Dalton, Georgia on March 4, 1864. He married Emiline Miley at Thonotosassa, Hillsborough County, Florida on April 3, 1870. He died while away from his home on January 28, 1876 at Pasco County, Florida. His place of interment is unknown. Emeline applied for and was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension for George’s service.[4][5][14][15]

- Private Robert L. Goldwire was born in September 1843 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He , along with two brothers and two sisters, was orphaned in 1853; they were taken in by their maternal grandmother, Sarah A. Lines. Madame Lines was a woman of some means; in 1860, she and the children were living near Quincy, Gadsden County Florida. Madame Lines reported a real estate worth of $40,000 and a personal worth of $80,000. All of the children in her care were enrolled in school within 12 months of the 1860 census. Robert enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was left sick at Gadsden County, Florida when his company left the state. He managed to rejoin the company on or about June 30, 1862 and was present with them until November 13 when he was transferred to the regimental band at Cumberland Gap, Tennessee. He returned from that assignment on May 13, 1863, and was assigned to guard duty with the city police at Knoxville, Tennessee from August 17–18, 1863. He was sent to a hospital at LaFayette, Georgia on September 13, 1863 for unknown reason. After his release from the hospital, he served on the Provost Guard[50] at La Grange, Georgia until January 1, 1864. He surrendered at Tallahassee, Florida on May 10, 1865 and took the Oath of Allegiance on May 15. His description is given as 5’ 9” height, dark hair, blue eyes, and dark complexion. The date and place of his death are unknown, as is the place of interment.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private H. A. Gore was born ca. 1842 in Georgia. In 1860 he was living near Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida at the residence of his father, Ellis, along with his mother and 6 brothers. He had attended school within 12 months of the census; his occupation was given as a laborer. “H.A.”, along with younger brother Jasper, enlisted in Davidson’s Company on May 2, 1862 at Rico’s Bluff, Liberty County, Florida. He was left sick at Gadsden County, Florida when his company left the state. He returned to the company prior to November 12, 1862. He was sent to a hospital at Knoxville, Tennessee on January 5, 1863, and was absent from the company from that date until about March 12, 1863. He was present with the company until July 1, when he was captured near Cowan, Tennessee during Bragg’s withdrawal from Tullahoma.[51] He was sent to the Military Prison at Louisville, Kentucky on July 15; he was reported as an inpatient at the Nashville Prison Hospital on August 8. He was reported to have died as a result of an accident at the hospital on October 1, 1863, and was interred in a local cemetery.[4][5][14][15]

- Private Jasper Gore was born ca. 1846 in Georgia. In 1860 he was living near Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida at the residence of his father, Ellis, along with his mother and 6 brothers. He had attended school within 12 months of the census; his occupation was given as a laborer. Jasper, along with older brother “H.A.”, enlisted in Davidson’s Company on May 2, 1862 at Rico’s Bluff, Liberty County, Florida. He was present with the company from the date of enlistment until January 27, 1863, when he died while in the Asylum Hospital at Knoxville, Tennessee. He is interred at Bethel Confederate Cemetery, Knoxville, Knox County, Tennessee.[4][5][14][15]

- Private John Allison Grubb was born on April 1, 1843 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. In 1860 he was living near Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida at the residence of his father, Nicholas, along with his mother, 2 brothers and 2 sisters. Enlisted September 21, 1861 at Pensacola, Escambia County, Florida in Captain Gee’s Company (Company G, 1st Florida Infantry) for a period of 12 months. He reenlisted in Captain Davidson’s Company on April 24, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was with the company from the date of enlistment until October 28, 1862 when he was reported sick at Knoxville, Tennessee. He remained at Knoxville, and was assigned as a hospital attendant on January 15, 1863; a week later, he was assigned as a ward master.[52] Between November and December, 1863 he was transferred from the Army of Tennessee by Secretary of War Special Order 264/25 dated November 6, 1863for service as a Clerk in the Department of Medicine, and assigned to the General Hospital at Quincy, Florida. He was paroled at Quincy on June 15, 1865. After the war, John moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he joined the Typographical Union, Local 3 ca. 1870. He relocated to Evansville, Indiana ca. 1874. He was employed by the Savannah Press for some 28 years. Private Gatlin applied for and was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. He was a confirmed bachelor. He died ca. 1915; his places of death and interment are unknown.[4][5][14][15]

- Private Thomas L. Grubb was born on December 29, 1830, at Quincey, Gadsden County, Florida. Married Julia Floria Tonis within 12 months of the 1860 census. In 1860 he and Julia were living near Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was by trade a carpenter. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was with the company when it departed the state, and was promoted to 5th Sergeant on August 1, 1862, most likely as a replacement for Byardim Garden Pringle, who had been detailed as Clerk and private secretary to Colonel Jesse J. Finley on May 1, 1862. He was detached from the company on December 20, 1862 for temporary service as a pork house guard at Knoxville, Tennessee until about April 27, 1863. On that date, he was granted a furlough of 30 days, which he took in Florida. His furlough was extended to July 23, 1863; he was reassigned from 5th Sergeant to 4th Sergeant on June 5. He did not return to duty until after February 1864; he had been reported as being sick at Quincy, Florida since the extension of his furlough. He was admitted to the Ocmulgee Hospital at Macon, Georgia on August 13, 1864 as a result of a gunshot wound that fractured the ring-finger knuckle of his right hand (likely during the Battle of Utoy Creek). He was released on August 17, with a medical furlough of 30 days at Gadsden County, Florida. He returned to the company and was present with it until he was captured at Egypt Station, Mississippi on December 28, 1864. He was transferred to the Military Prison, Alton, Illinois on January 17, 1865 and remained there until he was transferred to Point Lookout, Maryland for exchange on February 21, 1865. He is last documented as being a patient of General Hospital at Howard’s Grove, Richmond, Virginia where he died of continued fever on March 23, 1865. Private Grubb is interred at Oakwood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private Colin Campbell Gunn (older brother of William Campbell Gunn of the same company) was born June 28, 1842 at Walton County, Florida. In 1860 he was living near Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida at the residence of his father, Daniel, along with his mother, 2 brothers and 3 sisters, and was employed as a clerk. He enlisted April 5, 1861 at Pensacola, Escambia County, Florida in Captain Gee’s Company (Company G, 1st Florida Infantry) for a period of 12 months. He reenlisted in Captain Davidson’s Company on May 2, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was listed as absent sick at Gadsden County for the period from his enlistment until June 30; he was promoted to 2nd Sergeant on May 3, likely as the replacement for 2nd Sergeant Edward White who was promoted to 1st Sergeant on April 18. Colin was elected to 2nd Lieutenant on November 16, 1863, replacing Lieutenant Hugh Black who had been promoted to 1st Lieutenant on November 5, 1863. Lieutenant Campbell was present with the company until July 21, 1864 when he became ill near Atlanta, Georgia. He returned to duty sometime after September 18, 1864. He was wounded severely in the left thigh on March 19, 1865 at Bentonville, North Carolina and was admitted to C.S.A. General Hospital at Charlotte, North Carolina on April 6, 1865. He was transferred to a hospital at Columbus, Georgia on April 14, and remained there until his parole and discharge on May 12, 1865. He returned to Florida and settled near Marianna, Jackson County, Florida on February 6, 1869. He married Annie E. Rawls at Marianna on June 3, 1891. Lieutenant Gunn applied for and was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension. He died on May 25, 1916 at Marianna; his remains were transported and interred near his family at Euchee Valley Cemetery, Eucheeanna, Walton County, Florida.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private William Campbell Gunn (younger brother of Colin Campbell Gunn of the same company) was born on June 30, 1844 at Walton County, Florida. In 1860 he was living near Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida at the residence of his father, Daniel, along with his mother, 2 brothers and 3 sisters, and was employed as a clerk. He enlisted in Captain Davidson’s Company on March 17, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was absent sick for a period after his enlistment, but was present with the company when it departed the state. He was detailed for detached service on August 5, 1862 at Knoxville, Tennessee where he served as a clerk in the Medical Director’s office. He returned from that assignment prior to November 12, 1862 and was present with the company until April 12, 1863 when he was again detailed for detached service, this time as a clerk at Post Headquarters at Knoxville. He returned to the company on or about April 30, and was present with the company before again being detached for service by order of Major General Simon Bolivar Buckner on July 16, 1863. This assignment was to serve as a clerk to a Captain Somerville, A.C.S.[53] William would serve in this capacity until December 1863. He was reported present with the company from that time until July 22, 1864 when he was captured near Atlanta. He was sent to the Military Prison at Louisville, Kentucky and transferred from there on August 2 to Camp Chase, Ohio. He applied to take the oath of allegiance in November 1864, and was transferred to City Point, Virginia in March 1865. He married Martha Beneta Callaway on December 22, 1869 at Cuthbert, Georgia. William died on September 24, 1893, and is interred at Rosedale Cemetery, Cuthburt, Randolph County, Georgia.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private John James Hair was born ca. 1825 in Georgia. He resided in Baker County, Georgia until after 1845, the relocated to Gadsden County, Florida. In 1855, the part of Gadsden County in which he resided was separated from Gadsden County to become Liberty County. John married Eliza E. Butler of Gadsden County at Quincey on September 21, 1850. In 1860 he and Eliza were living near Bristol, Liberty County, Florida. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was rejected by an Inspecting Officer when the company was mustered into Confederate service on April 18, 1862.[36][54] Private Hair died ca. 1919, and is interred at Dead River Cemetery, Bruce, Walton County, Florida.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private James T. Harden was born ca. 1832 in Georgia. He married Elouisa Adaline Holstein at Midway, Gadsden County, Florida on January 7, 1858. In 1860 he and Elouisa were living near Midway, Gadsden County, Florida. He was by occupation a farmer, owned real estate valued at $500, and reported a personal worth of $200. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 12, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was left sick at Gadsden County, Florida when his company left the state. He was reported as absent without leave since June 11. According to Elouisa’s Florida Confederate pension application, James was on his way home on a sick furlough, and died at the home of his aunt, Mary Johnson, at Houston County, Georgia on November 25, 1862. Elouisa was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension for James’ service. His place of interment is unknown.[3][4][5][14][15]

- Private William Herrington was born ca. 1824 at Alexander, North Carolina. He married Rebecca Sikes prior to 1860 at Apalachicola, Gadsden County, Florida. He enlisted in Davidson’s Company on March 3, 1862 at Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida. He was left sick in Florida when the company left the state, and caught up with it after June 30, 1862. He was left sick in a hospital at Lexington, Kentucky on October 11, 1862. There is no further record of military service; however, Private William J. Ferrall attested in 1899 that he was with Private Herrington when he was mortally wounded in action at Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863. Rebecca applied for and, based on Ferrall’s statement, was awarded a Florida Confederate Pension for her husband’s service. His place of interment is unknown.[3][4][5][14]