Queensland Police Service

| Queensland Police Service | |

|---|---|

|

Logo of the Queensland Police Service | |

| Motto | With Honour We Serve |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 1 January 1864 |

| Legal personality | Governmental: Government agency |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction* | State of Queensland, Australia |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters |

200 Roma Street, Brisbane, QLD 4000 27°27′59″S 153°01′06″E / 27.4664°S 153.0182°ECoordinates: 27°27′59″S 153°01′06″E / 27.4664°S 153.0182°E |

| Police Officers | 11,971 (June 30 2016) |

| General Employees | 2794 (30 June 2016) |

| Police Commissioner responsible | Ian Stewart |

| Units |

List

|

| Website | |

| www.police.qld.gov.au/ | |

| Footnotes | |

| * Divisional agency: Division of the country, over which the agency has usual operational jurisdiction. | |

The Queensland Police Service (QPS) is the law enforcement agency responsible for policing the Australian state of Queensland. In 1990, the Queensland Police Force was officially renamed the Queensland Police Service and the old motto of "Firmness with Courtesy" was changed to "With Honour We Serve". The headquarters of the Queensland Police Service is located at 200 Roma Street, Brisbane.

Commissioner Ian Stewart is the present Commissioner of the Queensland Police Service. The Queensland Police marked 150 years of service to the state of Queensland on 1 January 2014.

History

Queensland as a state did not exist until 6 June 1859.[1] The area now called Queensland was known as North Eastern New South Wales. The colony would have been under the jurisdiction of the New South Wales Police Force up until Queensland established its own police force.

The Queensland Police were established on 1 January 1864 and started operations with approximately 143 employees, including the first Commissioner of Police D.T. Seymour. The service had four divisions: Metropolitan Police, Rural Police, Water Police, and Native Police. Police often worked a seven-day week, although they were entitled to every second Sunday free.[2] Bicycles were introduced in 1895. At the turn of the century there were 845 men and 135 Aboriginal trackers at 256 stations in Queensland.

1900s

In 1904 the Queensland Police started to use fingerprinting in investigations. In the 1912 Brisbane general strike the Queensland Police were used to suppress striking workers. The first female police officers were inducted in 1931 to assist in inquiries involving female suspects and prisoners. Following World War II a number of technological innovations were adopted including radio for communication within Queensland and between state departments. By 1950 the Service was staffed by 2,030 police officers, 10 women police and 30 trackers. In February 1951, a central communication room was established at the Criminal Investigation Branch in Brisbane.[3]

1960s and 1970s

On 14 May 1963, the Juvenile Aid Bureau was established.[3] In 1965 female officers were given the same powers as male officers. The Queensland Police Academy at Oxley, Brisbane, was completed in 1972. Bicycles were phased out in 1975 and more cars and motorcycles were put into service. The Air Wing also became operational in 1975 following the purchase of two single-engine aircraft.

1980s

The decade was a turbulent period in Queensland's political history. Allegations of high-level corruption in both the Queensland Police and State Government led to a judicial inquiry presided by Tony Fitzgerald. The Fitzgerald Inquiry which ran from July 1987 to July 1989 led to charges being laid against many long serving police, including Jack Herbert, Licensing Branch Sergeant Harry Burgess, Assistant Commissioner Graeme Parker[4] and Commissioner Terry Lewis. Lewis was jailed and served ten and a half years.

The Fitzgerald Inquiry also led to a perjury trial against former Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, which ended with a hung jury. The Director of Public Prosecutions elected not to pursue a retrial due to Bjelke-Petersen's age and health. It was later revealed that the jury foreman for the trial was a member of the Young Nationals and identified with the "friends of Joh" movement.

The Criminal Justice Commission was established in 1989 by the Queensland Criminal Justice Act 1989, following widespread corruption amongst high-level Queensland politicians and police officers being uncovered in the Fitzgerald Inquiry. It has since merged in 2002 with the Queensland Crime Commission to form the Crime and Misconduct Commission. The Criminal Justice Commission was responsible for significant research into the Queensland Police Service.

A new computerised message switching system was put into use throughout Queensland in 1980. At the time it was one of the most effective police communication systems in Australia.

1990s

The Police Powers and Procedures Act 1997 was passed by the Queensland Government on 1 July 1997 and took effect 6 April 1998. Law enforcement equipment introduced in the 1990s include oleoresin capsicum (OC) spray, the Smith & Wesson revolver firearm and later the Glock semi-automatic pistol, the long 26" baton to the 21" extendable baton, and linked to hinged handcuffs in 1998, and Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) laser-based detection devices and an Integrated Traffic Camera System in 1999 to enforce traffic speed limits.

2000s

The Police Powers and Responsibilities Act 2000[5] came into force in July 2000 which consolidated the majority of police powers into one Act. The Queensland Police contributed to the national CrimTrac system and the National Automated Fingerprint Identification System (NAFIS), established in 2000. The Crime and Misconduct Act 2001 commenced 1 January 2002 and redefined the responsibilities of the Service and the Crime and Misconduct Commission (CMC) with respect to the management of complaints. The CMC also has a witness protection function.[6] The CMC has investigative powers, not ordinarily available to the Queensland Police, for the purposes of enabling the commission to effectively investigate particular cases of major crime.[7] The CMC also has the power to investigate cases of misconduct in the Queensland public sector, particularly the more serious cases of misconduct.[7] In 2013, the CMC became the Crime and Corruption Commission.

In 2002 there were 8,367 police officers (20.2% female) and 2,925 staff members at 321 stations, 40 Police Beat shopfronts and 21 Neighbourhood Police Beats throughout the state. By 2004 the service grown to 9,003 police officers (21.8% female) and 2,994 other staff members. As at 30 June 2016 there were 11,971 police officers (26.3% female) and 2,794 other staff members.[8]

The Taser conducted electrical weapon (CEW) was trialled by some officers in 2006 and was eventually issued in 2009. In mid-2007, approximately 5,000 officers participated in the Pride in Policing march through Brisbane.

Criticisms

The Queensland Police Special Bureau was formed on 30 July 1940 and renamed Special Branch on 7 April 1948. It was criticised for being used for political purposes by the Bjelke-Petersen government in the 1970s and 1980s, such as enforcing laws against protests (sometimes outnumbering the protesters or using provocateurs to incite violence so the protesters could be arrested[9]) and investigating and harassing political opponents.[10] It was disbanded in 1989 following a recommendation by the Fitzgerald Inquiry into police corruption.[10] Special Branch destroyed its records before Fitzgerald could subpoena them.[10]

In 1994 six police officers, becoming known as the "Pinkenba Six", took three Aboriginal boys from Fortitude Valley and left them at Pinkenba as an unofficial way to punish the boys for suspected offences. The police officers were charged with abduction but were subsequently acquitted in court; the police service put them on twelve months probation for their errors of judgement.[11]

The Service has been accused of institutional racism after its fierce support of Senior Sergeant Chris Hurley who stood trial for the 2004 assault and manslaughter of Mulrunji Doomadgee. Senior Sergeant Hurley was initially subject of a Coronial Inquest by Coroner Christine Clements where he was found to have a case to answer despite conflicting medical evidence. The Director of Public Prosecutions Leanne Clare refused to place Senior Sergeant Hurley on trial for lack of evidence. After reviewing the evidence the Crime and Misconduct Commission (CMC) also found that there was insufficient evidence to prosecute for wrongdoing.[12] The Queensland Attorney General Kerry Shine ordered a review despite advice from the State Solicitor-General Walter Sofronoff QC highlighting the lack of evidence. A review by New South Wales Former Chief Justice Sir Laurence Street found there was a case to answer. Senior Sergeant Hurley was found not guilty by a jury in the Townsville Supreme Court and the findings of the Coronial Inquest were subsequently overturned by the Queensland District Court. The District Court ruled that Coroner's finding "..was against the weight of the evidence.."[13]

Also in 2006 and 2008 footage was caught of police beating homeless men after they were pinned to the ground.[14][15] It came a year after a report by organisations including the Queensland Council of Social Service (QCOSS) and community groups such as the Red Cross, which detailed widespread harassment by police of the socially vulnerable. Approximately 75% of interviewees made such claims, but the report was ignored by the government. Police Minister Judy Spence said of the report "At a cursory glance, it looks like a compendium of views from nameless, homeless people,".[16]

In 2008, the CMC investigated an officer after he used a Taser on a teenage girl at South Bank,[17] but recommended the officer only receive "managerial guidance". The incident was also against police policy to use tasers on minors. Police later charged the girl with breaching a move on order, but the case was thrown out with the magistrate criticising police's over-reaction.[18] A subsequent inquiry by the CMC into the use of the TASER by the Queensland Police Service found there was no systemic abuse of the device by officers, despite the chairman saying the incident "showed a concerning pattern within QPS towards the handling of policing incidents". CCTV video footage was released, delayed by possible civil action, showing the girl lashing out and kicking the officer, knocking the Taser out of his holster before he used it as she was held on the ground by two security guards.[19]

In June 2009 a man died after allegedly being tasered by Queensland police 28 times. The policeman in question claimed the deceased was tasered a much lower number of times, suggesting the device was making erroneous readings.[20] The coronial inquest later found this not to be the case, and that the officer tasered the man 28 times for up to five seconds at a time.[21]

In early 2010, raids were made by the CMC (Crime and Misconduct Commission) on police stations in Queensland.[22] The results of the raids and interrogations of police officers are being kept confidential, but come less than a year after a CMC report claiming

"the evidence revealed an attitude on the part of a not insignificant number of police officers, and their supervisors, that it was acceptable to act in ways that ignored legislative and QPS policy requirements, that were improper, and in some cases were dishonest and unlawful. Based on past experiences, the CMC had no confidence that the attitudes of those police officers would change without the pressure of public exposure."

The CMC report focused on police corruption, and not police brutality that accounted for ten times as many complaints in Surfers Paradise - 130 reports to 13 in the 18 months to March 2010.[23]

Positive contributions

Innovation

The innovation of the QPS has not gone unnoticed by other police jurisdictions. The field DNA sampling method and resources developed by QPS have since been introduced interstate. The QPS and QHFSS were awarded a Prime Minister’s Award for Excellence in Public Administration as a result of their successful collaboration to achieve this result. Four other police agencies have adopted the Forensic Register as their forensic case management system. The spread of this innovation is now improving the effectiveness of forensic science across Australia.[24]

Queensland Police, through their Twitter account (@QldPolice, formerly @QPSmedia), Facebook page (Queensland Police), Instagram (QldPolice) and YouTube channel (QueenslandPolice), have demonstrated world's best-practice emergency communications management through social media for their efforts through the 2011 Queensland floods and Cyclone Yasi.[25]

The Society For The Policing Of Cyberspace (POLCYB), based in Canada, announced the winners of the 2011 International Law Enforcement Cybercrime Award was the Queensland Police. Operation Achilles, the Taskforce Argos operation that led to the infiltration and dismantling of an international child sex offender network has been recognised for its significant contributions to reducing and preventing crimes against children.[26]

Brian Hay from the QPS Fraud and Corporate Crime Group, State Crime Operations Command won AusCERT Director’s Award for Individual Excellence in Information Security. The award is presented to the individual who in the past year most contributed to information security in the areas of community service, innovation, education, liaison, law enforcement, governance or leadership.[27]

In 2010 Queensland Police has been awarded the BMC Innovation award at this year’s IT Service Management (ITSM) industry awards for its implementation of a service design, namely Queensland Police Records Management Exchange (QPRIME) which amalgamated over 200 legacy systems.[28]

Queensland Police Party Safe Initiative recognised as a finalist in the National Drug And Alcohol Awards. The Queensland Police Service (QPS) Party Safe initiative has received recognition as a finalist in the 2008 National Drug and Alcohol Awards for Excellence in the Law Enforcement Category.[29]

Charity work

The Queensland Police Pipes and Drums band performed a benefit concert to raise money in conjunction with The Japan Foundation. All proceeds that were raised went to the Consulate of Japan for earthquake and tsunami victims.[30]

Doomadgee Police Bike Squad took on the challenge of a 100 km charity bike ride from Doomadgee to Burketown in October to show their support for the community. Bicycle patrols in the Doomadgee community were introduced in June this year to increase police interaction with community members. The Doomadgee community has come to embrace the police bike-squad, which is one of the first bicycle squads to be implemented in an indigenous township. The charity ride was proudly supported by community businesses who donated about $300 worth of sporting equipment for local youth initiatives and a further $300 was raised.[31]

Public relations

The Queensland Police are regarded as leaders in social media use, using Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Pinterest in addition to blogs and other websites. Their effective use of social media using the 2011 Queensland floods attracted a wide local following. By 2015, their Facebook page had attracted over 850,000 "likes" and it is believed 10% of the Queensland population follow their social media postings. Individual postings have achieved up to 60,000 "likes". The social media feeds contain a mix of content: reports of crimes, public safety notices, road and traffic conditions, human interest stories and humour, which often include running jokes such as Nickelback and One Direction being "wanted for crimes against music".[32]

A popular public relations program operated by the Queensland Police is "What the ? Friday", a weekly social media posting showing the most strange or foolish situation encountered by the police that week. The posting typically involves a photo and some amusing but informative commentary. These attract a great deal of public interest and comment both on social media and beyond. The police leave the missing word in the title to the public's imagination but it is likely that "what the fuck?" is implied as this is a common but vulgar Australian expression of surprise.[33][34]

Another popular public relations program involves the Queensland Police dogs and particularly their puppy training program taking advantage of the often viral success of postings of puppies on social media sites. The public get to suggest names for the puppies and follow their upbringing and training.[35] The program has been so successful that the Queensland Police publish calendars illustrated with police dog photos which are sold to the public to raise funds for charities.[36]

The police take advantage of their social media following to seek information from the public about offences, often with positive results. For example, in 2012, a Facebook post about a murder attracted responses from seven eyewitnesses in less than 24 hours.[33]

Regions

Between 1991 and 2013 there were eight geographic regions (Far Northern, Northern, Central, North Coast, Metropolitan North, Metropolitan South, Southern, and South Eastern), three commands (State Crime Operations, Operations Support, and Ethical Standards), and four divisions (Human Resources, Finance, Administration, and Information Management).

As of 2017, there are five police regions and eight commands in the State of Queensland, each under command of an Assistant Commissioner:

- Regional Operations

- Northern Region

- Central Region

- Brisbane Region

- Southern Region

- South Eastern Region

- Specialist Operations

- Community Contact Command

- Intelligence, Counter-Terrorism and Major Events Command

- Operations Support Command

- State Crime Command

- Road Policing Command

- Commonwealth Games Group

- Strategy, Policy and Performance

- Crime and Corruption Commission Police Group

- Ethical Standards Command

- Legal Division

- Organisational Capability Command

- People Capability Command

These regions are further divided into districts and further still into divisions. Separately, a new government department, Public Safety Business Agency took over the portfolios of human resources, finance, administration, education and training, and information technology).

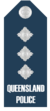

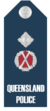

Ranks and structure

The Queensland Police Service has two classes of uniformed personnel: police officers ('sworn' and 'unsworn'),[lower-alpha 1] and staff members (public servants or 'civilian': police liaison officers, watchhouse officers, and pipes and drums musicians). Both classes wear the same blue uniform with shoulder patches, however:

- 'Recruits' are required to replace the chequered band on their wide-brimmed hats with a plain blue piece;

- pipes and drums musicians have hard board epaulettes and with pipes and drums wording;

- police liaison officers (PLOs) are distinguished by a yellow chequered band and a 'Police Liaison Officer' badge; and

- watchhouse officer have grey epaulettes stating 'watchhouse officer'.

As of 2015 all rank insignia is now on "ink dark" background with insignia embroidered in white. There has been the addition of a "recognition of service" horizontal bar between rank insignia and the words "Queensland Police" for officers who have been on rank for a period of five years. This "recognition of service" is only for the ranks Senior Constable, Sergeant and Senior Sergeant.

Ranks of the Queensland Police Service are as follows:

Staff members

- Torres Strait Island Police Support Officer (green/white/blue epaulette with embroidered 'TORRES STRAIT ISLAND POLICE SUPPORT OFFICER' and rank)

- Police Liaison Officer (yellow or blue/green (Torres Strait) epaulette with embroidered 'POLICE LIAISON OFFICER')

- Recruit (light blue epaulette with embroidered 'POLICE RECRUIT')

Constable ranks

- Constable (one embroidered chevron)

- Senior Constable (two embroidered chevrons)

Non-commissioned ranks

- Sergeant (three embroidered chevrons)

- Senior Sergeant (embroidered crown with laurels)

Commissioned ranks

- Inspector (three pips)

- Superintendent (one crown and one pip)

- Chief Superintendent (one crown and two pips)

- Assistant Commissioner (crossed tipstaves with laurels)

- Deputy Commissioner (one pip and crossed tipstaves with laurels)

- Commissioner (one crown and crossed tipstaves with laurels)

| Constable | Senior Constable | Sergeant | Senior Sergeant | Inspector | Superintendent | Chief Superintendent | Assistant Commissioner | Deputy Commissioner | Commissioner |

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

Rank insignia is worn only by uniformed officers. Prior to mid-2009, only officers at the rank of inspector and above (commissioned officers) had the words 'Queensland Police' embroidered on their epaulettes, however new uniform mandates saw the introduction of the words 'Queensland Police' on all epaulettes issued to police officers after this date. The epaulettes of commissioned officers are significantly larger than the epaulettes of lesser ranks. Different paypoints apply within the same rank relative to years of service.

Specialist areas

Officers must serve a minimum of three years in general duties before being permitted to serve in specialist areas such as:

- Child Protection and Investigation Unit (CPIU), formerly the Juvenile Aid Bureau (JAB)

- Criminal Investigation Branch (CIB)

- Dog Squad

- Forensic Crash Unit, formerly the Accident Investigation Squad (AIS), and before that, the Traffic Accident Investigation Squad (TAIS)

- Forensic Services Branch

- Mounted

Mounted Police patrolling campgrounds

Mounted Police patrolling campgrounds - Prosecutions

- Railway Squad

- Scenes of Crime

- Special Emergency Response Team (SERT)

- Stock and Regional Crime Investigation Squad (SARCIS), formerly the Stock Squad

- Road Policing Units (RPU), formerly Traffic Branch

- Intelligence Analyst

- Water Police

- Public Safety Response Team (PSRT)

- District Education and Training Office (DETO)

- Radio & Electronics Section (RES)

- Police Citizens Youth Club (PCYC)

- Tactical Crime Squad

Commissioners

The following list chronologically records those who have held the post of Commissioner of the Queensland Police Service.

| Name | Post-nominals | Term began | Term ended | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| David Thompson Seymour | 1864 | 1895 | ||

| William Parry-Okeden | 1895 | 1905 | ||

| William Geoffrey Cahill | 1905 | 1916 | ||

| Frederic Charles Urquhart | 1917 | 1921 | ||

| Patrick Short | 1921 | 1925 | ||

| William Harold Ryan | 1925 | 1934 | ||

| Cecil James Carroll | MC, MVO | 1934 | 1949 | |

| John Smith | LVO | 1949 | 1954 | |

| Patrick Glynn | 1955 | 1957 | ||

| Thomas William Harrold | 1957 | 1957 | ||

| Frank Bischof | LVO, QPM | 1958 | 1969 | |

| Norm Bauer | LVO, QPM | 1969 | 1970 | |

| Ray Whitrod | CVO, QPM | 1970 | 1976 | |

| Sir Terence Murray Lewis | OBE, GM, QPM | 1976 | 1987 | Lewis was subsequently stripped of his knighthood, OBE and QPM in 1993. |

| Ron Redmond | APM, QPM | 1987 | 1989 | Acting |

| Noel Newnham | APM | 1989 | 1992 | |

| Jim O'Sullivan | APM | 1992 | 2002 | |

| Bob Atkinson | APM | 2000 | 2012 | |

| Ian Stewart | APM | 2012 | Incumbent | [37] |

Equipment

Standard equipment issued and worn on duty belt by a uniformed police officer:

- Glock 22 pistol .40-calibre

- 2 x magazines plus ammunition

- ASP extendable baton (21") concealed within pouch

- Saflok Mk5 hinged handcuffs

- Motorola radio and radio pouch

- OC (oleoresin capsicum) spray within pouch

Supplier of belt and pouches is TripleB Leathercraft.

Other equipment provided to officers include:

- Maglite

- light weight medic gloves and voice recording devices

As of 2011 officers around the state may also carry a Taser (X26) with spare air cartridge, which are both contained within a specially designed holster. In late 2013, officers started trialling Apple iPads and iPhones to access the operational computer QPRIME, given the name 'QLiTE'.

Officers around the state now have an option of an equipment vest which is designed to transfer the weight from the hips to the torso. The vest holds the radio, handcuffs and OC spray.

Vehicles

Vehicles currently in use with the Queensland Police Service:

- Ford Falcon (sedan, station wagon and ute XR6 Turbo variant used by Highway patrol)

- Ford Territory

- Ford Mondeo (unmarked)

- FPV F6 sedan

- Holden Captiva (unmarked)

- Holden Commodore (sedan, current station wagon and ute, also unmarked post-2006 model wagons)

- Holden Commodore SS (Highway Patrol)

- Holden Crewman (with prisoner compartment)

- Holden Rodeo (discontinued) with prisoner compartment

- Holden HSV R8 SVR (Highway Patrol, 'Fatal 4' markings) [38]

- Honda Accord Euro (unmarked)

- Honda ST1300 motorcycle

- Hyundai i20 (unmarked)

- Hyundai i30 (unmarked)

- Hyundai i40

- Hyundai iLoad van

- Hyundai ix35

- Hyundai Santa Fe

- Isuzu D-Max (also used by forensic officers)

- Iveco Daily (dual cab, unmarked, mounted division)

- Mazda 6 (unmarked)

- Mercedes-Benz Sprinter van

- Mercedes-Benz Vito van

- Mitsubishi Lancer (unmarked)

- Mitsubishi Pajero

- Mitsubishi Triton (with prisoner compartment)

- Nissan Patrol

- Nissan X-Trail

- Subaru Liberty (unmarked)

- Toyota Aurion

- Toyota Camry Hybrid

- Toyota Hilux (with prisoner compartment, also unmarked)

- Toyota Kluger

- Toyota Land Cruiser 200 series

- Toyota Land Cruiser Prado

- Toyota RAV4

- Volkswagen Golf (unmarked)

- Volkswagen Jetta (unmarked)

- BMW R1200RS motorcycle (unmarked)

- Yamaha FJR1300 motorcycle

The SERT (Special Emergency Response Team) unit also has two specialised armoured vehicles, Lenco BearCats, at its disposal for use in riot control and other potentially dangerous situations throughout the Brisbane/South Eastern and Northern police regions, with one vehicle stationed in Brisbane and Cairns each.

From 1996 to 2015, nominated vehicles were fitted with other 200 in-car computers supplied by the state transport department, the Mobile Integrated Network Data Access (MINDA) units. From April 2012, automatic number plate recognition technology was fitted to road policing unit vehicles, follow earlier trials.[39][40][41]

Queensland Police has received its first police helicopter, based on the Gold Coast in 2012. The helicopter was used for a six-month trial period. The highly anticipated $1.6 million Bell 206 Long Ranger has already been hailed a success, assisting police in 24 different dispatches in its first three days of operation, and will be used extensively during major events such as Schoolies Week and the Gold Coast 600. The helicopter is fitted out with state-of-the-art equipment such as infrared and thermal imaging cameras, and other equipment based on the NSW Police Force helicopters. A second helicopter a BO 105 was introduced by July 2014 in time for the G20 summit in November, responsible for patrolling Brisbane and the Sunshine Coast.[42]

In a first for an Australian police department, Queensland Police have purchased numerous unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs; i.e. drones) which have already been used for surveillance purposes in numerous situations where sending in officers is deemed too risky such as during sieges or hostage rescue operations.

Queensland Water Police operate three purpose-designed 23m patrol vessels and numerous smaller rigid-hulled inflatable boats.

Queensland police killed in the line of duty

- 29 May 2017: Senior Constable Brett Forte was shot and killed at Adare, north of Gatton, after attempting to apprehend a suspected offender. The gunman, Rick Maddison, was shot and killed the next day by police while trying to escape after a siege in a farmhouse at Ringwood, north-west of Gatton[43]

- 29 May 2011: Detective Senior Constable Damien Leeding (CIB) was shot when he confronted an armed offender at the Pacific Pines Tavern on the Gold Coast. Leeding died in hospital on 1 June three days after being shot.[44]

- 19 July 2007: Constable Brett Irwin, 33, was shot while executing an arrest warrant for breach of bail at Keperra, in northwest Brisbane.[44]

- 22 August 2003: Senior Sergeant Perry Irwin, 42, was shot while investigating reports of gunfire in bushland at Caboolture, north of Brisbane.[44]

- 21 July 2000: Senior Constable Norman Watt, 33, was shot during an armed stand-off near Rockhampton, central Queensland.[44]

- 21 May 1996: Constable Shayne Gill, Struck by a motor vehicle while on radar duty on the Bruce Highway near Glasshouse Mountains.[45]

- 29 June 1989: Constable Brett Handran was shot attending a domestic dispute in Wynnum, in east Brisbane.[44]

- 29 July 1987: Senior Constable Peter Kidd was shot in a raid at Virginia, in north Brisbane.[46]

- 29 February 1984: Constable Michael Low was shot attending a domestic dispute at North Rockhampton, central Queensland.[46]

- 2 November 1975: Senior Constable Lyle Hoey was deliberately run down by a car near Mount Molloy in North Queensland.[46]

- 9 April 1969: Senior Constable Colin Brown was shot while investigating the behaviour of a farm employee on a property near Dayboro, north of [46]Brisbane.

- 27 March 1968: Constable Douglas Gordon was shot attending a domestic disturbance at Inala, in south Brisbane.[46]

- 26 October 1964: Senior Constable Desmond Trannore was shot attending a domestic disturbance near Gordonvale, North Queensland.[46]

- 14 February 1963: Senior Constable Cecil Bagley was electrocuted when he tried to rescue a neighbour being electrocuted in his car.[47]

- 16 August 1962: Constable Douglas Wrembeck stopped to question a motorist in South Brisbane and was killed when he was struck by a car driven by a hit-and-run driver.[47]

- 19 February 1962: Constable Gregory Olive was shot in the chest at close range when he knocked on a front door to make inquiries at Kelvin Grove.[47]

- 1 April 1956: Constable First Class Roy Doyle died in hospital at Mackay from head injuries sustained when he hit a submerged block of concrete while attempting a rescue in the flooded Pioneer River at Mackay on 29 March 1956.[47]

- 27 September 1906: Sergeant Thomas Heaney died at South Brisbane from head fractures sustained when he was hit multiple times over the head with a metal bar during an arrest on 7 June 1905 at Woolloongabba.[47]

- 23 December 1905: Constable Albert Price was stabbed while making an arrest at Mackay.[47]

- 16 September 1904: Constable First Class Charles O'Kearney was knocked down by a horse being deliberately ridden towards him in retaliation for an arrest in Laidley.[47]

- 29 March 1903: Acting Sergeant David Johnston was killed by being hit on the head with an axe by a prisoner in the watchhouse at Mackay.[48]

- 30 March 1902: Constable George Doyle was shot while attempting to capture the Kenniff brothers, who had a long history of stealing cattle and horses, in Upper Warrego.[48]

- 2 July 1895: Senior Constable William Conroy was stabbed several times trying to prevent a man from stabbing the man's wife onThursday Island.[48]

- 6 September 1894: Constable Edward Lanigan was shot in the chest while trying to prevent another policeman from being shot during an arrest at Montalbion (a mining town near Irvinebank).[48]

- 10 May 1894: Constable Benjamin Ebbitt died at South Brisbane having never recovered from an assault during an arrest on 9 November 1890 at Croydon.[48]

- 4 February 1893: Constable James Sangster drowned attempting a rescue of two people during a flood of the Bremer River at North Ipswich.[48]

- 27 October 1889: Senior Constable Alfred Wavell was shot at Corinda (southwest of Burketown) by a man who had escaped from the Normanton lock-up.[48]

- 26 January 1883: Constable William Dwyer was struck on the head by a tomahawk by an Aboriginal near Juandah Station via Taroom.[49]

- 24 January 1883: Cadet Sub-Inspector Mark Beresford was speared in the thigh and hit on the head by Aboriginals in the Selwyn Ranges to the south of Cloncurry.[49]

- 24 September 1881: Sub-Inspector Henry Kaye was speared through the chest by Aboriginals at Woolgar gold fields (100km north of Richmond).[49]

- 24 January 1881: Sub-Inspector George Dyas was found buried after being speared in the back by Aboriginals while he camped near the 40 Mile Waterhole near Normanton.[49]

- 6 November 1867: Constable Patrick Cahill and Constable John Power were poisoned and shot in the head at the MacKenzie River Crossing while escorting a consignment of bank notes and bullion from Rockhampton to Clermont.[49]

Former members

- Terry Lewis

- Francis Bischof

- Wayne Bennett (rugby league)

- Mal Meninga

- Dan Crowley

- Michael Featherstone

- Domenico Cacciola

See also

Notes

- ↑ Each state legislation defines the organisational structure and terms. In Queensland, employees are either police officers, staff members, or police recruits, collectively referred to as 'members of the Service'. The Police Service Administration Regulation 1990 provides an oath of office ('sworn') and affirmation of office ('unsworn'). The latter caters for a variety of police officers including those who have atheist religious beliefs.

References

- ↑ "Documenting Democracy". Letters Patent erecting Colony of Queensland 6 June 1859 (UK). National Archives of Australia. 1859. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- ↑ [http://www.police.qld.gov.au>about us]

- 1 2 http://www.police.qld.gov.au>about us

- ↑ Whitton, Evan (12 May 2007). "When the Sunshine State set up a scoundrel trap". The Australian. Archived from the original on 17 May 2007. Retrieved 14 May 2007.

- ↑ "Police Powers and Responsibilities Act 2000" (PDF). Queensland State Government. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ↑ Crime And Misconduct Act 2001 - Section 56. Queensland Consolidated Acts. Retrieved on 4 July 2011.

- 1 2 Crime And Misconduct Act 2001 - Section 5. Queensland Consolidated Acts. Retrieved on 4 July 2011.

- ↑ "QPS 2007-2008 Annual Report" (PDf). Queensland Police Service. 30 June 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- ↑ "The making of civil liberties". Courier-Mail. 13 October 2007.

- 1 2 3 "Inside Queensland's spy unit". Brisbane Times. 7 April 2010.

- ↑ Chang, Charis (26 April 2017). "One Nation candidate Mark Ellis receives death threats over controversial past". news.com.au. News Limited. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ↑ "Beattie defends Palm Island role". Brisbane Times. 21 June 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ "Judge overturns Mulrunji Doomadgee death finding". ABC. 19 December 2008. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ "Queensland police caught on camera". ABC. 21 July 2008. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ↑ "Caught on camera: Qld Police punching homeless man". ABC. 22 July 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ↑ "Qld police 'persecute poor, indigenous'". Ninemsn. 14 June 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ↑ "Officer 'quietly' subdued girl before she was tasered". Brisbane Times. 7 March 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ↑ "CMC critical of officer over Taser incident". Brisbane Times. 4 March 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ↑ "16 year old girl tasered in South Bank". Youtube. 6 March 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ↑ "Taser death: stun gun fired 28 times". ABC. 18 June 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ↑ "Qld man not killed by Taser: coroner". ABC. 14 November 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ↑ "Police corruption fit for Hollywood". ABC News. 9 February 2010. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ↑ "Gold Coast police are the most complained about". The Courier-Mail. 15 March 2010. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ↑ "QPS forensic innovation". QPS. 29 June 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ↑ "Queensland Police demonstrate best practice emergency communications management via social media". Craig Thomler's professional blog. 24 January 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ↑ "2011 International Law Enforcement Cybercrime Award". The Society For The Policing Of Cyberspace. 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ↑ "Winners and Finalists 2010". AusSERT. 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ↑ "Queensland Police Takes BMC Innovation Award". CIO. 14 September 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ "Queensland Police Party Safe Initiative recognised as a finalist in the National Drug And Alcohol Awards". National Drug & Alcohol. 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ "Queensland Police Pipes and Drums raises money for Japan" (PDF). The Japan Foundation. May 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ↑ "Police ride for their community, Doomadgee". QPS Media. 4 November 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ↑ "How Queensland Police Service gets 60,000 likes on Facebook posts - Marketing Magazine". Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- 1 2 "Cops are funny on social media. But should they ever be seen as "one of us"? | Courtney Robinson". the Guardian. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ↑ "Queensland Police pins crims on Pinterest - mUmBRELLA". Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ↑ "Name the police puppy - QPS News". Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ↑ "Queensland paw enforcement calendar to raise money for charity". Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ↑ "Stewart named as new Qld Police Commissioner". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 3 September 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ↑ Stevens, Mike (6 December 2011). "HSV ClubSport R8 SV-R Rolled Out For Queensland Police Patrols". The Motor Report. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ↑ Queensland Government (September 2008). "Inquiry into Automatic Number Plate Recognition technology". Queensland parliamentary committees. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ Queensland Government (15 April 2011). "Automatic number plate recognition technology to be rolled out on Qld roads". Ministerial statements. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ Queensland Government (7 August 2013). "Police target crime with new technology". Ministerial statements. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ Queensland Government (1 July 2014). "Queensland’s second police helicopter launched". Ministerial statements. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ Kate Kyriacou; Thomas Chamberlin; Chris Clarke; David Sigston (30 May 2017). "Cop killer shot dead by police". The Courier Mail. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "ROLL OF HONOUR 1989 - 2011". Queensland Police. Archived from the original on 1 June 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ↑ "In Remembrance: 1986-1996". Queensland Police. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "ROLL OF HONOUR 1964 - 1987". Queensland Police. Archived from the original on 1 June 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "ROLL OF HONOUR 1904 - 1963". Queensland Police. Archived from the original on 1 June 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "ROLL OF HONOUR 1889 - 1903". Queensland Police. Archived from the original on 1 June 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "ROLL OF HONOUR 1867 - 1883". Queensland Police. Archived from the original on 1 June 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

External links

- Queensland Police Service

- Public Safety Business Agency

- Dangerous Liaisons - CMC investigation, July 2009

- G.E. Fitzgerald (1989) "Report of a Commission of Inquiry Pursuant to Orders in Council" Commission of Inquiry into Possible Illegal Activities and Associated Police Misconduct Queensland Government Printer.

- Two books about crime and corruption in the Queensland police—Gold Coast Writers Association, 2014.

- Queensland Police Service: Disaster management and social media: a case study

- "Queensland Police Commissioners". Queensland Police. Retrieved 23 February 2016.