M1911 pistol

| United States Pistol, Caliber .45, M1911 | |

|---|---|

|

A Remington Rand Model 1911A1 of the U.S. Army | |

| Type | Semi-automatic pistol |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1911–present |

| Used by | 28 nations, see Users below for details |

| Wars |

As standard U.S. service pistol: World War I World War II Korean War Vietnam War In non-standard use: Irish war of independence Indonesian National Revolution Persian Gulf War War in Afghanistan Iraq War Syrian Civil War |

| Production history | |

| Designer | John Browning |

| Designed | 1911[1] and 1924 (A1) |

| Manufacturer | Colt Manufacturing Company |

| Produced | 1911–present |

| No. built | Over 2.7 million |

| Variants |

M1911A1[1] M1911A2[2] RIA Officers |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 2.44 lb (1.105 kg) empty, w/magazine[1][3] |

| Length | 8.25 in (210 mm)[1] |

| Barrel length |

Government model: 5.03 in (127 mm)[1] Commander model: 4.25 in (108 mm) Officer's ACP model: 3.5 in (89 mm) |

|

| |

| Cartridge | .45 ACP |

| Action | Short recoil operation[1] |

| Muzzle velocity | 825 ft/s (251 m/s) |

| Feed system | 7 round standard detachable box magazine[1] |

The M1911 is a single-action, semi-automatic, magazine-fed, recoil-operated pistol chambered for the .45 ACP cartridge.[1] It served as the standard-issue sidearm for the United States Armed Forces from 1911 to 1986. It was first used in later stages of the Philippine–American War, and was widely used in World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. The pistol's formal designation as of 1940 was Automatic Pistol, Caliber .45, M1911 for the original model of 1911 or Automatic Pistol, Caliber .45, M1911A1 for the M1911A1, adopted in 1924. The designation changed to Pistol, Caliber .45, Automatic, M1911A1 in the Vietnam War era.[1]

The U.S. procured around 2.7 million M1911 and M1911A1 pistols in military contracts during its service life. The M1911 was replaced by the 9mm Beretta M9 pistol as the standard U.S. sidearm in October 1986, but due to its popularity among users, it has not been completely phased out. Modernized derivative variants of the M1911 are still in use by some units of the U.S. Army Special Forces, the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps.[4]

Designed by John Browning, the M1911 is the best-known of his designs to use the short recoil principle in its basic design. The pistol was widely copied, and this operating system rose to become the preeminent type of the 20th century and of nearly all modern centerfire pistols. It is popular with civilian shooters in competitive events such as USPSA, IDPA, International Practical Shooting Confederation, and Bullseye shooting. Compact variants are popular civilian concealed carry weapons in the U.S. because of the design's relatively slim width and stopping power[5] of the .45 ACP cartridge.[6]

History

Early history and adaptations

The M1911 pistol originated in the late 1890s as the result of a search for a suitable self-loading (or semi-automatic) pistol to replace the variety of revolvers then in service.[7] The United States was adopting new firearms at a phenomenal rate; several new pistols and two all-new service rifles (the M1892/96/98 Krag and M1895 Navy Lee), as well as a series of revolvers by Colt and Smith & Wesson for the Army and Navy, were adopted just in that decade. The next decade would see a similar pace, including the adoption of several more revolvers and an intensive search for a self-loading pistol that would culminate in official adoption of the M1911 after the turn of the decade.

Hiram S. Maxim had designed a self-loading rifle in the 1880s, but was preoccupied with machine guns. Nevertheless, the application of his principle of using cartridge energy to reload led to several self-loading pistols in 1896. The designs caught the attention of various militaries, each of which began programs to find a suitable one for their forces. In the U.S., such a program would lead to a formal test at the turn of the 20th century.[8]

During the end of 1899 and start of 1900, a test of self-loading pistols was conducted, which included entries from Mauser (the C96 "Broomhandle"), Mannlicher (the Mannlicher M1894), and Colt (the Colt M1900).[7]

This led to a purchase of 1,000 DWM Luger pistols, chambered in 7.65mm Luger, a bottlenecked cartridge. During field trials these ran into some problems, especially with stopping power. Other governments had made similar complaints. Consequently, DWM produced an enlarged version of the round, the 9×19mm Parabellum (known in current military parlance as the 9×19mm NATO), a necked-up version of the 7.65 mm round. Fifty of these were tested as well by the U.S. Army in 1903.[9]

American units fighting Moro guerrillas during the Philippine–American War using the then-standard Colt M1892 revolver, .38 Long Colt, found it to be unsuitable for the rigors of jungle warfare, particularly in terms of stopping power, as the Moros had high battle morale and often used drugs to inhibit the sensation of pain.[10] The U.S. Army briefly reverted to using the M1873 single-action revolver in .45 Colt caliber, which had been standard during the late 19th century; the heavier bullet was found to be more effective against charging tribesmen.[11] The problems prompted the then–Chief of Ordnance, General William Crozier, to authorize further testing for a new service pistol.[11]

Following the 1904 Thompson-LaGarde pistol round effectiveness tests, Colonel John T. Thompson stated that the new pistol "should not be of less than .45 caliber" and would preferably be semi-automatic in operation.[11] This led to the 1906 trials of pistols from six firearms manufacturing companies (namely, Colt, Bergmann, Deutsche Waffen und Munitionsfabriken (DWM), Savage Arms Company, Knoble, Webley, and White-Merrill).[11]

Of the six designs submitted, three were eliminated early on, leaving only the Savage, Colt, and DWM designs chambered in the new .45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) cartridge.[11] These three still had issues that needed correction, but only Colt and Savage resubmitted their designs. There is some debate over the reasons for DWM's withdrawal—some say they felt there was bias and that the DWM design was being used primarily as a "whipping boy" for the Savage and Colt pistols,[12] though this does not fit well with the earlier 1900 purchase of the DWM design over the Colt and Steyr entries. In any case, a series of field tests from 1907 to 1911 were held to decide between the Savage and Colt designs.[11] Both designs were improved between each testing over their initial entries, leading up to the final test before adoption.[11]

Among the areas of success for the Colt was a test at the end of 1910 attended by its designer, John Browning. Six thousand rounds were fired from a single pistol over the course of two days. When the gun began to grow hot, it was simply immersed in water to cool it. The Colt gun passed with no reported malfunctions, while the Savage designs had 37.[11]

Service history

Following its success in trials, the Colt pistol was formally adopted by the Army on March 29, 1911, when it was designated Model of 1911, later changed to Model 1911, in 1917, and then M1911, in the mid-1920s. The Director of Civilian Marksmanship began manufacture of M1911 pistols for members of the National Rifle Association in August 1912. Approximately 100 pistols stamped "N.R.A." below the serial number were manufactured at Springfield Armory and by Colt.[13] The M1911 was formally adopted by the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps in 1913.

World War I

By the beginning of 1917, a total of 68,533 M1911 pistols had been delivered to U.S. armed forces by Colt Firearms Company and the U.S. government's Springfield Armory. However, the need to greatly expand U.S. military forces and the resultant surge in demand for the firearm in World War I saw the expansion of manufacture to other contractors besides Colt and Springfield Armory, including Remington-UMC, North American Arms Co. of Quebec.[14] Several other manufacturers were awarded contracts to produce the M1911, including the National Cash Register Company, the Savage Arms Company, the Caron Bros. of Montreal, the Burroughs Adding Machine Co., Winchester Repeating Arms Company, and the Lanston Monotype Company, but the signing of the Armistice resulted in the cancellation of the contracts before any pistols had been produced.

Interwar changes

Battlefield experience in World War I led to some more small external changes, completed in 1924. The new version received a modified type classification, M1911A1, in 1926 with a stipulation that M1911A1s should have serial numbers higher than 700,000 with lower serial numbers designated M1911.[15] The M1911A1 changes to the original design consisted of a shorter trigger, cutouts in the frame behind the trigger, an arched mainspring housing, a longer grip safety spur (to prevent hammer bite), a wider front sight, a shortened hammer spur, and simplified grip checkering (eliminating the "Double Diamond" reliefs).[11] These changes were subtle and largely intended to make the pistol easier to shoot for those with smaller hands. Many persons unfamiliar with the design are often unable to tell the difference between the two versions at a glance. No significant internal changes were made, and parts remained interchangeable between the M1911 and the M1911A1.[11]

Working for the U.S. Ordnance Office, David Marshall Williams developed a .22 training version of the M1911 using a floating chamber to give the .22 long rifle rimfire recoil similar to the .45 version.[11] As the Colt Service Ace, this was available both as a pistol and as a conversion kit for .45 M1911 pistols.[11]

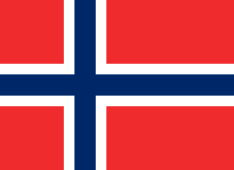

Before World War II, a small number of modified M1911-pattern pistols in .45 caliber were produced under license by the Norwegian arms factory Kongsberg Vaapenfabrikk, designated "Pistol M/1914" and unofficially known as "Kongsberg Colt". Production continued after the German occupation of Norway in 1940. The Pistol M/1914 is noted for its unusual extended slide stop which was specified by Norwegian ordnance authorities. Throughout the M/1914's use in Norwegian military service, Norway continued to build the M/1914 pistol as originally specified. These pistols are highly regarded by modern collectors, with the 920 examples stamped with German Army inspectors proof (Waffenamt) codes and the unknown number of unmarked examples assembled by the Norwegian resistance movement (the "Matpakke-Colt" or "Lunch Box Colt") being the most sought after. German forces also used captured M1911A1 pistols, using the designation "Pistole 660(a)".[16]

The M1911 and M1911A1 pistols were also ordered from Colt or produced domestically in modified form by several other nations, including Argentina (Modello 1916 and Modello 1927 contract pistols), and the Ballester–Molina), Brazil (M1937 contract pistol), Mexico (M1911 Mexican contract pistol and the Obregón pistol), and Spain (private manufacturers Star and Llama).

World War II

World War II and the years leading up to it created a great demand. During the war, about 1.9 million units were procured by the U.S. Government for all forces, production being undertaken by several manufacturers, including Remington Rand (900,000 produced), Colt (400,000), Ithaca Gun Company (400,000), Union Switch & Signal (50,000), and Singer (500). New M1911A1 pistols were given a parkerized metal finish instead of blueing, and the wood grip panels were replaced with panels made of brown plastic. The M1911A1 was a favored small arm of both US and allied military personnel during the war, in particular, the pistol was prized by some British commando units and the SOE as well as Commonwealth South African forces.[17][18][19]

So many 1911A1 pistols were produced during the war that the government cancelled all postwar contracts for new production, instead choosing to rebuild existing pistols with new parts, which were then refinished and tested for functioning. From the mid-1920s to the mid-1950s thousands of 1911s and 1911A1s were refurbished at U.S. Arsenals and Service depots. These arsenal rebuilds consisted of anything from minor inspections to major overhauls of pistols returned from service use. Pistols that were refurbished at Government arsenals will usually be marked on the frame/receiver with the arsenal's initials, such as RIA (Rock Island Armory) or SA (Springfield Armory).

Among collectors today, the Singer-produced pistols in particular are highly prized, commanding high prices even in poor condition.[20]

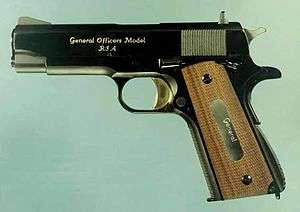

General Officer's Model

From 1943 to 1945 a fine-grade russet-leather M1916 pistol belt set was issued to some generals in the US Army. It was composed of a leather belt, leather enclosed flap-holster with braided leather tie-down leg strap, leather two-pocket magazine pouch, and a rope neck lanyard. The metal buckle and fittings were in gilded brass. The buckle had the seal of the U.S. on the center (or "male") piece and a laurel wreath on the circular (or "female") piece. The pistol was a standard-issue M1911A1 that came with a cleaning kit and three magazines.

From 1972 to 1981 a modified M1911A1 called the RIA M15 General Officer's Model was issued to General Officers in the US Army and US Air Force. From 1982 to 1986 the regular M1911A1 was issued. Both came with a black leather belt, open holster with retaining strap, and a two-pocket magazine pouch. The metal buckle and fittings were similar to the M1916 General Officer's Model except it came in gold metal for the Army and in silver metal for the Air Force. The M15 and M1911A1 were replaced with the M9 pistol in 1986.

Replacement for most uses

After World War II, the M1911 continued to be a mainstay of the U.S. Armed Forces in the Korean War and the Vietnam War. It was used during Desert Storm in specialized U.S. Army units and U.S. Navy Mobile Construction Battalions (Seabees), and has seen service in both Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom, with U.S. Army Special Forces Groups and Marine Corps Force Reconnaissance Companies.[21]

However, by the late 1970s, the M1911A1 was acknowledged to be showing its age. Under political pressure from Congress to standardize on a single modern pistol design, the U.S. Air Force ran a Joint Service Small Arms Program to select a new semi-automatic pistol using the NATO-standard 9 mm Parabellum pistol cartridge. After trials, the Beretta 92S-1 was chosen. The Army contested this result and subsequently ran its own competition in 1981, the XM9 trials, eventually leading to the official adoption of the Beretta 92F on January 14, 1985.[22][23][24] By the late 1980s production was ramping up despite a controversial XM9 retrial and a separate XM10 reconfirmation that was boycotted by some entrants of the original trials, cracks in the frames of some pre-M9 Beretta-produced pistols, and despite a problem with slide separation using higher-than-specified-pressure rounds that resulted in injuries to some U.S. Navy special operations operatives. This last issue resulted in an updated model that includes additional protection for the user, the 92FS, and updates to the ammunition used.[25]

By the early 1990s, most M1911A1s had been replaced by the Beretta M9, though a limited number remain in use by special units. The U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) in particular were noted for continuing the use of M1911 pistols for selected personnel in MEU(SOC) and reconnaissance units (though the USMC also purchased over 50,000 M9 pistols.) For its part, the United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) issued a requirement for a .45 ACP pistol in the Offensive Handgun Weapon System (OHWS) trials. This resulted in the Heckler & Koch OHWS becoming the MK23 Mod 0 Offensive Handgun Weapon System (itself being heavily based on the 1911's basic field strip), beating the Colt OHWS, a much modified M1911. Dissatisfaction with the stopping power of the 9 mm Parabellum cartridge used in the Beretta M9 has actually promoted re-adoption of pistols based on the .45 ACP cartridge such as the M1911 design, along with other pistols, among USSOCOM units in recent years, though the M9 remains predominant both within SOCOM and in the U.S. military in general.[21]

Current users in the U.S.

Many military and law enforcement organizations in the U.S. and other countries continue to use (often modified) M1911A1 pistols including Marine Corps Special Operations Command, Los Angeles Police Department SWAT and S.I.S., the FBI Hostage Rescue Team, FBI regional SWAT teams, and 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment—Delta (Delta Force).

The M1911A1 is popular among the general public in the U.S. for practical and recreational purposes. The pistol is commonly used for concealed carry thanks in part to a single-stack magazine (which makes for a thinner pistol that is, therefore, easier to conceal), personal defense, target shooting, and competition. Numerous aftermarket accessories allow users to customize the pistol to their liking. There are a growing number of manufacturers of M1911-type pistols and the model continues to be quite popular for its reliability, simplicity, and patriotic appeal. Various tactical, target and compact models are available. Price ranges from a low end of around $400 for basic pistols imported from the Philippines or Turkey (Armscor, Tisas, Rock Island Armory, Girsan, STI Spartan, Seraphim Armoury) to more than $4,000 for the best competition or tactical versions (Wilson Combat, Ed Brown, Les Baer, Nighthawk Custom, and STI International).[26]

Due to an increased demand for M1911 pistols among Army Special Operations units, who are known to field a variety of M1911 pistols, the U.S. Army Marksmanship Unit began looking to develop a new generation of M1911s and launched the M1911-A2 project in late 2004.[2] The goal was to produce a minimum of seven variants with various sights, internal and external extractors, flat and arched mainspring housings, integral and add-on magazine wells, a variety of finishes and other options, with the idea of providing the end-user a selection from which to select the features that best fit their missions.[2] The AMU performed a well-received demonstration of the first group of pistols to the Marine Corps at Quantico and various Special Operations units at Ft. Bragg and other locations.[2] The project provided a feasibility study with insight into future projects.[2] Models were loaned to various Special Operations units, the results of which are classified. An RFP was issued for a Joint Combat Pistol but it was ultimately canceled.[2] Currently units are experimenting with an M1911 pistol in .40 which will incorporate lessons learned from the A2 project. Ultimately, the M1911A2 project provided a test bed for improving existing M1911s. An improved M1911 variant becoming available in the future is a possibility.[2]

The Springfield Custom Professional Model 1911A1 pistol is produced under contract by Springfield Armory for the FBI regional SWAT teams and the Hostage Rescue Team.[27] This pistol is made in batches on a regular basis by the Springfield Custom Shop, and a few examples from most runs are made available for sale to the general public at a selling price of approximately US$2,700 each.

MEU(SOC) pistol

Marine Expeditionary Units formerly issued M1911s to Force Recon units.[28] Hand-selected Colt M1911A1 frames were gutted, deburred, and prepared for additional use by the USMC Precision Weapon Section (PWS) at Marine Corps Base Quantico.[28] They were then assembled with after-market grip safeties, ambidextrous thumb safeties, triggers, improved high-visibility sights, accurized barrels, grips, and improved Wilson magazines.[29] These hand-made pistols were tuned to specifications and preferences of end users.[30]

In the late 1980s, the Marines laid out a series of specifications and improvements to make Browning's design ready for 21st century combat, many of which have been included in MEU (SOC) pistol designs, but design and supply time was limited.[30] Discovering that the Los Angeles Police Department was pleased with their special Kimber M1911 pistols, a single source request was issued to Kimber for just such a pistol despite the imminent release of their TLE/RLII models.[31] Kimber shortly began producing a limited number of what would be later termed the Interim Close Quarters Battle pistol (ICQB). Maintaining the simple recoil assembly, 5-inch barrel (though using a stainless steel match grade barrel), and internal extractor, the ICQB is not much different from Browning's original design.[31]

In late July 2012, the U.S. Marines placed a $22.5 million order for 12,000 M1911 pistols for MEU(SOC) forces.[4] The new 1911 was designated M45A1 or "Close Quarters Battle Pistol" CQBP. The M45A1 features a dual recoil spring assembly, Picatinny rails and is cerakoted tan in color.

International users

- Bangladesh still uses USGI M1911s supplied as military aid during the Vietnam War era while Rapid Action Battalion (RAB Forces), an anti-terrorist police tactical team in Bangladesh uses this weapon.[32]

- The Brazilian company IMBEL (Indústria de Material Bélico do Brasil) still produces the pistol in several variants for military and law enforcement uses in .45 ACP, .40 S&W and 9 mm calibres. The two former are also available to Army-registered collectors and shooters. For the civilian market, the pistols are chambered in .380 ACP since there are strong calibre restrictions in place. Also, produces for US civilian market as the supplier to Springfield Armory.

- The Canadian company Seraphim Armoury brands Filipino manufactured pistols in several models for domestic and export use. Pistols are available in .45 ACP and 9 mm calibres for civilian, military and law enforcement use.

- A Chinese Arms manufacturer, Norinco, exports a clone of the M1911A1 for civilian purchase as the M1911A1 and the high-capacity NP-30, as well 9mm variants the NP-28 and NP-29. Norinco also manufactured conversion kits to chamber the 7.62×25mm Tokarev round after the Korean War.[33]

- As of 2013, the pistol is made under license instead of copying with Colt manufacturing machinery, due to an agreement between Norinco and Colt in order to stop Norinco from producing the Norinco CQ rifle. Importation into the United States was blocked by trade rules in 1993 but Norinco still manages to import the weapon into Canada and successfully adopted by IPSC shooters, gunsmiths and firearms enthusiasts there because of the cheaper price of the pistol than the other M1911s.

- The German Volkssturm used captured M1911s at the end of World War II under the weapon code P.660(a), in which the alphabet means "Amerika", the weapons' origin country.[34][35]

- The Greek Hellenic Army issues the World War II production American M1911 as sidearm. These pistols are supplied as military aid in 1946 and afterward as the U.S. aided Greece against Communist expansion.[36]

- Norway used the Kongsberg Colt which was a license produced variant and is recognized by the unique slide catch. Many Spanish firearms manufacturers produced pistols derived from 1911, such as the STAR Model B, the ASTRA 1911PL, and the Llama Model IX, just to name a few.[37] Argentina produced a licensed copy, the Model 1927 Sistema Colt, which eventually led to production of the cheaper Ballester–Molina, which resembles the 1911, but is not actually based on it.

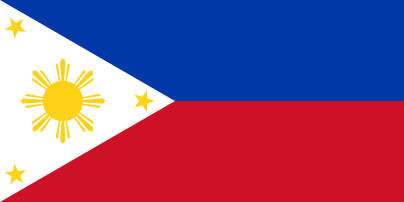

- The Armed Forces of the Philippines issues Mil-spec M1911A1 pistols as a sidearm to the special forces, military police, and officers. These pistols are mostly produced by Colt, though some of them are produced locally by Armscor, a Philippine company specialized in making 1911-style pistols. The Indonesian Army issued a locally produced version of the Springfield M1911, chambered in .45 ACP along with the Pindad P1, the locally manufactured Browning Hi-Power pistol as the standard issue sidearm.

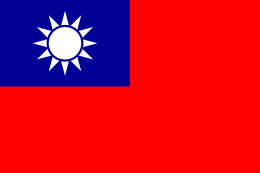

- In the 1950s, the Republic of China Army (Taiwan) used original M1911A1s, and the batches are now still used by some forces. In 1962, Taiwan copied the M1911A1 as the T51 pistol, and it saw limited use in the Army. After that, the T51 was improved and introduced for export as the T51K1. Now the pistols in service are replaced by locally-made Beretta 92 pistols- the T75 pistol.

- The Royal Thai Army and Royal Thai Police uses the Type 86, the Thai copy of the M1911 chambered in the .45 ACP round,[33]

- The Turkish Land Forces uses "MC 1911" Girsan made copy of M1911.[38]

- Numbers of Colt M1911s were used by the Royal Navy as sidearms during World War I in .455 Webley Automatic caliber.[11] The pistols were then transferred to the Royal Air Force where they saw use in limited numbers up until the end of World War II as sidearms for air crew in event of bailing out in enemy territory.[11] Some units of the South Korean Air Force still use these original batches as officers' sidearms.

Civilian models

- Colt Government Mk. IV Series 70 (1970–1983): Introduced the accurized Split Barrel Bushing. The first 1000 prototypes in the serial number range 35800NM – 37025NM were marked BB on the barrel and the slide. Commander sized pistols retained the solid bushing.

- Colt Government Mk. IV Series 80 (1983–present): Introduced an internal firing pin safety and a new half-cock notch on the sear; pulling the trigger on these models while at half-cock will cause the hammer to drop. Models after 1988 returned to the solid barrel bushing due to concerns about breakages.

- Colt 1991 Series (1991–2001 ORM; 2001–present NRM): A hybrid of the M1911A1 military model redesigned to use the slide of the Mk. IV Model 80; these models aimed at providing a more "mil-spec" pistol to be sold at a lower price point than Colt's other 1911 models in order to compete with imported pistols from manufacturers such as Springfield Armory and Norinco. The 1991–2001 model used a large "M1991A1" rollmark engraved on the slide. The 2001 model introduced a new "Colt's Government Model" rollmark engraving. The 1991 series incorporates full-sized blued and stainless models in either .45 ACP or .38 Super, as well as blued and stainless Commander models in .45 ACP.

Custom models

Since its inception, the M1911 has lent itself to easy customization. Replacement sights, grips, and other aftermarket accessories are the most commonly offered parts. Since the 1950s and the rise of competitive pistol shooting, many companies have been offering the M1911 as a base model for major customization. These modifications can range from changing the external finish, checkering the frame, and hand fitting custom hammers, triggers, and sears. Some modifications include installing compensators and the addition of accessories such as tactical lights and even scopes.[39] A common modification of John Browning's design is to use a full-length guide rod that runs the full length of the recoil spring. This adds weight to the front of the pistol, but does not increase accuracy, and does make the pistol slightly more difficult to disassemble.[40] Custom guns can cost over $5000 and are built from the ground up or on existing base models.[41] The main companies offering custom M1911s are: Springfield Custom Shop, Ed Brown, STI International, Nighthawk Custom, Wilson Combat, and Les Baer. IPSC models are offered by both Strayer Voigt Inc (Infinity Firearms) and STI International.

Design

Browning's basic M1911 design has seen very little change throughout its production life.[1] The basic principle of the pistol is recoil operation.[1] As the expanding combustion gases force the bullet down the barrel, they give reverse momentum to the slide and barrel which are locked together during this portion of the firing cycle. After the bullet has left the barrel, the slide and barrel continue rearward a short distance.[1]

At this point, a link pivots the rear of the barrel down, out of locking recesses in the slide, and the barrel is stopped by making contact with the lower barrel lugs against the frame's vertical impact surface. As the slide continues rearward, a claw extractor pulls the spent casing from the firing chamber and an ejector strikes the rear of the case, pivoting it out and away from the pistol. The slide stops and is then propelled forward by a spring to strip a fresh cartridge from the magazine and feed it into the firing chamber. At the forward end of its travel, the slide locks into the barrel and is ready to fire again.[1]

There are no fasteners of any type in the 1911 design, excepting the grip screws. The main components of 1911 are held in place by the force of the recoil spring. The pistol can be "field stripped" by partially retracting the slide, removing the slide stop, and subsequently removing the barrel bushing. Full disassembly (and subsequent reassembly) of the pistol to its component parts can be accomplished using several manually removed components as tools to complete the disassembly.

The military mandated a grip safety and a manual safety.[1] A grip safety, sear disconnect, slide stop, half cock position, and manual safety (located on the left rear of the frame) are on all standard M1911A1s.[1] Several companies have developed a firing pin block safety. Colt's 80 series uses a trigger operated one and several other manufacturers, including Kimber and Smith & Wesson, use a Swartz firing-pin safety, which is operated by the grip safety.[42][43] Language cautioning against pulling the trigger with the second finger was included in the initial M1911 manual, and later manuals up to the 1940s.[44]

The same basic design has been offered commercially and has been used by other militaries. In addition to the .45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol), models chambered for .38 Super, 9×19mm Parabellum, 7.65mm Parabellum, 9mm Steyr,[45] .400 Corbon, and other cartridges were offered. The M1911 was developed from earlier Colt designs firing rounds such as .38 ACP. The design beat out many other contenders during the government's selection period, during the late 1890s and early 1900s, up to the pistol's adoption. The M1911 officially replaced a range of revolvers and pistols across branches of the U.S. armed forces, though a number of other designs have seen use in certain niches.[46]

Despite being challenged by newer and lighter weight pistol designs in .45 caliber, such as the Glock 21, the SIG Sauer P220, the Springfield XD and the Heckler & Koch USP, the M1911 shows no signs of decreasing popularity and continues to be widely present in various competitive matches such as those of USPSA, IDPA, IPSC, and Bullseye.[2]

Users

-

Argentina[11]

Argentina[11] -

Bangladesh: Rapid Action Battalion[47]

Bangladesh: Rapid Action Battalion[47] -

Brazil: The Brazilian Army uses a version of the M1911 developed by IMBEL chambered in 9×19mm Parabellum and designated M973.[48][49]

Brazil: The Brazilian Army uses a version of the M1911 developed by IMBEL chambered in 9×19mm Parabellum and designated M973.[48][49] -

Bolivia[50][51]

Bolivia[50][51] -

Canada: In both World Wars, Canadian officers had the option of privately purchasing their own sidearm and the M1911/M1911A1 was a popular choice. The joint Canadian-US First Special Service Force (aka "The Devil's Brigade") also used American infantry weapons, including the M1911A1.[52]

Canada: In both World Wars, Canadian officers had the option of privately purchasing their own sidearm and the M1911/M1911A1 was a popular choice. The joint Canadian-US First Special Service Force (aka "The Devil's Brigade") also used American infantry weapons, including the M1911A1.[52] -

People's Republic of China: Norinco exports a clone of the M1911A1 for civilian purchase. The Chinese arms company also manufactured conversion kits to chamber the 7.62×25mm Tokarev round after the Korean War.[33][50][51]

People's Republic of China: Norinco exports a clone of the M1911A1 for civilian purchase. The Chinese arms company also manufactured conversion kits to chamber the 7.62×25mm Tokarev round after the Korean War.[33][50][51] -

Colombia[50][51]

Colombia[50][51] -

Costa Rica[50][51]

Costa Rica[50][51] -

Dominican Republic[50][51]

Dominican Republic[50][51] -

East Timor[53]

East Timor[53] -

Egypt[51] used by Unit 777

Egypt[51] used by Unit 777 -

Ecuador[51]

Ecuador[51] -

Fiji[50]

Fiji[50] -

Finland Used captured guns

Finland Used captured guns -

France[54]

France[54] -

Greece[36]

Greece[36] -

Guatemala[51][55]

Guatemala[51][55] -

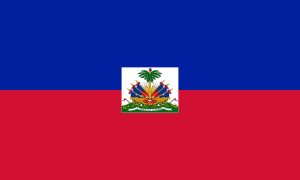

Haiti[50][51]

Haiti[50][51] -

Indonesia[55]

Indonesia[55] -

Iran[50][55]

Iran[50][55] -

Japan: After World War II Japan Self-Defense Forces and Police were provided the M1911A1 from US and were used until 1980s.[56]

Japan: After World War II Japan Self-Defense Forces and Police were provided the M1911A1 from US and were used until 1980s.[56] -

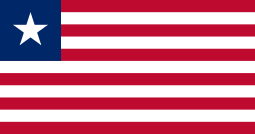

Liberia[50]

Liberia[50] -

Lithuania: Lithuanian Armed Forces[57]

Lithuania: Lithuanian Armed Forces[57] -

Luxembourg: In service with 1st Artillery Battalion 1963–1967.[58]

Luxembourg: In service with 1st Artillery Battalion 1963–1967.[58] -

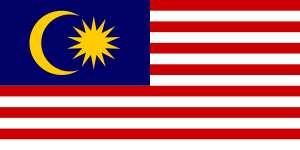

Malaysia: In service with Grup Gerak Khas special forces of the Malaysian Army[59]

Malaysia: In service with Grup Gerak Khas special forces of the Malaysian Army[59] -

Mexico[50][51][55]

Mexico[50][51][55] -

.svg.png) Nazi Germany: Used captured pistols during World War II.[11]

Nazi Germany: Used captured pistols during World War II.[11] -

Nicaragua[50][51]

Nicaragua[50][51] -

Norway[11]

Norway[11] -

North Korea: Used by North Korean Special forces and Presidential Guard.[60]

North Korea: Used by North Korean Special forces and Presidential Guard.[60] -

Philippines[50]

Philippines[50] -

Papua New Guinea[61]

Papua New Guinea[61] -

Poland: Polish Armed Forces in the West used pistols during World War II.[62]

Poland: Polish Armed Forces in the West used pistols during World War II.[62] -

Spain[63]

Spain[63] -

South Korea: Made under license by S&T Daewoo and used by Republic of Korea Air Force as officers' sidearms.[11]

South Korea: Made under license by S&T Daewoo and used by Republic of Korea Air Force as officers' sidearms.[11] -

South Vietnam[11]

South Vietnam[11] -

Soviet Union: Used by communist revolutionaries to murder the Russian imperial family in July 1918.[64] Thousands of pistols were received as military assistance during World War II.[63]

Soviet Union: Used by communist revolutionaries to murder the Russian imperial family in July 1918.[64] Thousands of pistols were received as military assistance during World War II.[63] -

Republic of China (Taiwan)[50]

Republic of China (Taiwan)[50] -

Thailand[33]

Thailand[33] -

Turkey[65]

Turkey[65] -

United Kingdom[11]

United Kingdom[11] -

United States: Former standard-issue service pistol of the U.S. Armed forces. The pistol remains in service with various law enforcement agencies across the U.S, such as the FBI, along with some US Special Operations soldiers.[63] The U.S. Marine Corps ordered 12,000 M1911 pistols for its Special Operations Capable Forces in July 2012.[4][66]

United States: Former standard-issue service pistol of the U.S. Armed forces. The pistol remains in service with various law enforcement agencies across the U.S, such as the FBI, along with some US Special Operations soldiers.[63] The U.S. Marine Corps ordered 12,000 M1911 pistols for its Special Operations Capable Forces in July 2012.[4][66] -

Zimbabwe[50]

Zimbabwe[50]

Specifications

- Cartridge: .45 ACP

- Other commercial and military derivatives: Other versions offered include .22, .38 Super, 9×19mm Parabellum, .40 S&W, 10mm Auto, .400 Corbon, .460 Rowland, .22 LR, .50 GI, .455 Webley, 9×23mm Winchester, and others. The most popular alternative versions are 9×19mm Parabellum, .38 Super and 10mm Auto.

- Barrel: 5 in (127 mm) Government, 4.25 in (108 mm) Commander, and the 3.5 in (89 mm) Officer's ACP. Some modern "carry" guns have significantly shorter barrels and frames, while others use standard frames and extended slides with 6 in (152 mm) barrels

- Rate of twist: 16 in (406 mm) per turn, or 1:35.5 calibers (.45 ACP)

- Operation: Recoil-operated, closed breech, single action, semi-automatic

- Weight (unloaded): 2 lb 7 oz (1.1 kg) (government model)

- Height: 5.25 in (133 mm)

- Length: 8.25 in (210 mm)

- Capacity: 7+1 rounds (7 in standard-capacity magazine +1 in firing chamber); 8+1 in aftermarket standard-size magazine; 10+1 in extended and high capacity magazines.[67] Guns chambered in .38 Super and 9 mm have a 9+1 capacity. Some manufacturers, such as Armscor, Para Ordnance, Strayer Voigt Inc and STI International Inc, offer 1911-style pistols using double-stacked magazines with significantly larger capacities (typically 14 rounds). Colt makes their own 8 round magazines which they include with their Series 80 XSE models.

- Safeties: A grip safety, sear disconnect, slide stop, a half cock position, and manual safety (located on the left rear of the frame) are on all standard M1911A1s. Several companies have developed a firing pin block. Colt's 80 series uses a trigger operated one and several other manufacturers (such as Smith & Wesson) use one operated by the grip safety.

State firearm

On March 18, 2011, the U.S. state of Utah—as a way of honoring M1911 designer John Browning, who was born and raised in the state—adopted the Browning M1911 as the "official firearm of Utah".[68]

Similar pistols

See also

- List of U.S. Army weapons by supply catalog designation (SNL B-6)

- Solid Concepts 1911DMLS

- Table of handgun and rifle cartridges

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Pistol, Caliber .45, Automatic, M1911 Technical Manual TM 9-1005-211-34 1964 edition. Pentagon Publishing. 1964. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-60170-013-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Garrett, Rob. "Army Marksmanship Unit: The Pipeline for Spec Ops Weapons". Tactical Weapons Magazine. 1 (1). Harris Publications, Inc.

- ↑ FM 23-35, 1940

- 1 2 3 Vasquez, Maegan (28 July 2012). "Sticking to their guns: Marines place $22.5M order for the Colt .45 M1911". Fox News. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ↑ durysguns.com (2006-01-14). "Which Handgun Round Has the Best Stopping Power?". Retrieved 2006-01-14.

- ↑ Ayoob, Massad (2007). The Gun Digest Book of Combat Handgunnery. Gun Digest Books. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-89689-525-6.

- 1 2 Taylor, Chuck (1981). Complete Book Of Combat Handgunning. Boulder, CO: Paladin Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-87364-327-6.

- ↑ Hogg, Ian V.; John Walter (2004). Pistols of the World (4 ed.). David & Charles. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-87349-460-1.

- ↑ Hogg (2004) p. 98

- ↑ Linn, Brian McAllister. The Philippine War, 1899–1902 (Modern War Studies (Paperback)). University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1225-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Poyer, Joseph; Craig Riesch; Karl Karash (2008). The Model 1911 and Model 1911A1 Military and Commercial Pistols. North Cape Publications. p. 544. ISBN 978-1-882391-46-2.

- ↑ Hallock, Kenneth R. (1980), Hallock's .45 Auto Handbook.

- ↑ Ness, Mark American Rifleman June 1983 p. 58

- ↑ Hogg (2004) p. 83

- ↑ Canfield, Bruce N. American Rifleman June 2005, p. 26

- ↑ axishistory.com (2008-03-28). "Axis History Factbook: Handguns". Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Bishop, Chris (1998). The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II. New York: Orbis Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7607-1022-8.

- ↑ Dunlap, Roy, Ordnance Went Up Front, Samworth Press (1948), p. 160

- ↑ Thompson, Leroy, The Colt 1911 Pistol, Osprey Press, ISBN 1849084335, 978-1849084338 (2011), p. 48

- ↑ "Singer Manufacturing Co. 1941 1911A1". Retrieved 2012-05-13.

- 1 2 Campbell, Robert K. (2011). The Shooter's Guide to the 1911: A Guide to the Greatest Pistol of All Time. Gun Digest Books. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-4402-1434-9.

- ↑ "AROUND THE NATION; Italian 9-mm. Chosen To Replace Army's .45". The New York Times. January 15, 1985.

- ↑ Biddle, Wayne (January 20, 1985). "COLT .45 GOES TO THE TROPHY ROOM". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Army Signs Pact For Beretta Guns". The New York Times. April 11, 1985.

- ↑ Malloy, John (2011). "The Colt 1911: The First Century". In Dan Shiedler. Gun Digest 2011. Krause. pp. 108–117. ISBN 978-1-4402-1337-3.

- ↑ Sweeney, Patrick (2010). 1911: The First 100 Years. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4402-1115-7.

- ↑ Us FBI Academy Handbook. International Business Publications. 2002. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7397-3185-7.

- 1 2 Clancy, Tom (1996). Marine: A Guided Tour of a Marine Expeditionary Unit. Berkeley, California: Berkeley Trade. pp. 64, 79–80. ISBN 978-0-425-15454-0.

- ↑ Hopkins, Cameron (March 1, 2002). "Semper FI 1911 – Industry Insider". American Handgunner (March–April, 2002).

- 1 2 Johnston, Gary Paul.(2004)"One Good Pistol", Soldier of Fortune Magazine, December 2004, 62–67

- 1 2 Rogers, Patrick A.(2003)"Marines New SOCOM Pistol", SWAT Magazine, December 2003, 52–57

- ↑ "Bangladesh Military Forces M1911". bdmilitary.com. 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- 1 2 3 4 Small Arms Illustrated, 2010.

- ↑ Scarlata, Paul (February 20, 2011). "Small Arms of the Deutscher Volkssturm". Shotgun News. p. 24.

- ↑ "Handguns". Axis History Factbook. Retrieved 2011-05-27.

- 1 2 "Greek Military". Greek Military. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ↑ "Firearm Review, June 2000". Cruffler.com. Retrieved 2008-09-08.

- ↑

- ↑ Thompson, Leroy; Rene Smeets (October 1, 1993). Great Combat Handguns: A Guide to Using, Collecting and Training With Handguns. London: Arms & Armour Publication. p. 256. ISBN 978-1-85409-168-0.

- ↑ Charles E. Petty. "Full length guide rods – myth or magic?". American Handgunner (September–October 2003 ed.).

- ↑ Rauch, Walt (2002). Practically Speaking: An Illustrated Guide; the Game, Guns and Gear of the International Defensive Pistol Association. Rauch & Company, Ltd. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-9663260-1-7.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 2,169,084 (1939)

- ↑ Davis and Raynor(1976), Safe Pistols Made Even Safer, American Rifleman, Jan. 1976

- ↑ 1912 Military Manual on the 1911, p. 16, at Google Books (published in 1912)

- ↑ Wiley Clapp. "The 1911: Not Just a .45". American Rifleman. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

- ↑ Hogg, Ian V.; John S. Weeks (2000). Military Small Arms of the 20th Century. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publication. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-87341-824-9.

- ↑ "M1911 Pistol | Bangladesh Military". Bdmilitary.com. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- ↑ ": Exército Brasileiro – Braço Forte, Mão Amiga :". Exercito.gov.br. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ↑ "Indústria de Material Bélico do Brasil – Pistola 9 M973". IMBEL. Archived from the original on January 24, 2006. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Hogg, Ian (1989). Jane's Infantry Weapons 1989–90, 15th Edition. Jane's Information Group. pp. 826–836. ISBN 0-7106-0889-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Latin American Light Weapons National Inventories". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved November 30, 2012. Citing Gander, Terry J.; Hogg, Ian V., eds. (1995). Jane's Infantry Weapons, 1995–1996 (21st ed.). Jane's Information Group. ISBN 9780710612410. OCLC 32569399.

- ↑ http://www.canadiansoldiers.com/weapons/pistols.htm

- ↑ https://sites.google.com/site/worldinventory/wiw_as_easttimor

- ↑ Thompson, Leroy (2011). The Colt 1911 Pistol. Osprey Publishings. p. 27. ISBN 9781849084338.

- 1 2 3 4 Jones, Richard (2009). Jane's Infantry Weapons 2009–2010. Jane's Information Group. pp. 896, 897, 899. ISBN 0-7106-2869-2.

- ↑ エリートフォーセス 陸上自衛隊編[Part2]. Hobby Japan. 2006. p. 62. ISBN 4-89425-485-9.

- ↑ "Pistoletas COLT M1911A1". Lietuvos kariuomenė [Lithuanian Armed Forces official Web site] (in Lithuanian). LR Krašto apsaugos ministerija [Ministry of National Defence Republic of Lithuania]. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

- ↑ GRAND-DUCHY OF LUXEMBOURG

- ↑ IBP USA (2007). Malaysia Army Weapon Systems Handbook. Int'l Business Publication. pp. 71–73. ISBN 978-1-4330-6180-6.

- ↑ http://bemil.chosun.com/nbrd/gallery/view.html?b_bbs_id=10044&pn=1&num=177361

- ↑ Alpers, Philip (2010). Karp, Aaron, ed. The Politics of Destroying Surplus Small Arms: Inconspicuous Disarmament. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge Books. pp. 168–169. ISBN 978-0-415-49461-8.

- ↑ Current site about uniforms and guns of Polish Army in II world war

- 1 2 3 Diez, Octavio (2000). Armament and Technology: Handguns. Lema Publications, S.L. ISBN 84-8463-013-7.

- ↑ Rappaport, The Last Days of the Romanovs: Tragedy at Ekaterinburg (2009), p. 181

- ↑ Standard Catalog of Military Firearms: The Collector's Price and Reference Guide, p. 323, at Google Books

- ↑ Sanborn, James K. "Elite Marine Corps units to field new pistols". Marine Corps Times, 19 July 2012.

- ↑ John Connor. "The $4.95 .45". American Handgunner (January–February 2007 ed.).

- ↑ Martinez, Michael (2011-03-19). "Add this to Utah's list of state symbols: an official firearm". CNN.

Further reading

- Meadows, Edward S. U.S. Military Automatic Pistols: 1894–1920. Richard Ellis Publications, 1993.

- The Bluejackets' Manual, 12th edition. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute, 1944.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to M1911. |

- Sam Lisker's Colt Automatic Pistols Home Page

- The M1911 Magazine FAQ

- The Thompson-LaGarde Cadaver Tests of 1904

- M1911 Pistols Organization main page, Detailed animated drawing of all operational parts and Syd's 1911 Notebook on M1911.org

- Exploded-View Diagram of an M1911 from American Rifleman

- Black Army Colt 1911

- Colt Model 1911A1 pistol (infographic tech. drawing)

- Colt Model 1911 pistol (infographic tech. drawing)