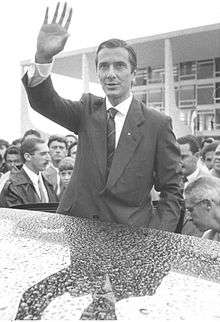

Fernando Collor de Mello

| His Excellency Fernando Collor de Mello | |

|---|---|

Collor's official photo as senator | |

| 32nd President of Brazil | |

|

In office March 15, 1990 – December 29, 1992 Suspended: October 2, 1992 – December 29, 1992 | |

| Vice President | Itamar Franco |

| Preceded by | José Sarney |

| Succeeded by | Itamar Franco |

| Member of the Federal Senate from Alagoas | |

|

Assumed office February 1, 2007 | |

| Preceded by | Heloísa Helena |

| 55th Governor of Alagoas | |

|

In office March 15, 1987 – May 14, 1989 | |

| Vice Governor | Moacir de Andrade |

| Preceded by | José Tavares |

| Succeeded by | Moacir de Andrade |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

|

In office February 1, 1983 – February 1, 1987 | |

| Constituency | Alagoas |

| 57th Mayor of Maceió | |

|

In office January 1, 1979 – January 1, 1983 | |

| Preceded by | Dílton Simões |

| Succeeded by | Corinto Campelo |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Fernando Affonso Collor de Mello August 12, 1949 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Political party |

Christian Labour Party (2016–present) |

| Other political affiliations |

Democratic Social Party (1979–1986) Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (1986–1989) National Reconstruction Party (1989–1993) Brazilian Labour Renewal Party (2000–2007) Brazilian Labour Party (2007–2016) |

| Spouse(s) |

Celi Elisabete Júlia Monteiro de Carvalho (1975–1981) Rosane Brandão Malta (1981–2005) Caroline Serejo Medeiros (2006–present) |

| Residence | Maceió, Alagoas |

| Alma mater | University of Brasília[1] |

| Profession | Entrepreneur, economist |

| Signature |

|

Fernando Affonso Collor de Mello (Portuguese pronunciation: [feʁˈnɐ̃du aˈfõsu ˈkɔloʁ dʒi ˈmɛlu]; born August 12, 1949) is a Brazilian politician who served as the 32nd President of Brazil from 1990 to 1992, when he resigned in a failed attempt to stop his trial of impeachment by the Brazilian Senate. Collor was the first President directly elected by the people after the end of the Brazilian military government. He became the youngest President in Brazilian history, taking office at the age of 40.

After his resignation from the presidency, the impeachment trial on charges of corruption continued, and Collor was found guilty by the Senate and sentenced to disqualification from holding elected office for eight years (1992–2000). He was later acquitted of ordinary criminal charges in his judicial trial before Brazil's Supreme Federal Court, for lack of valid evidence.

Fernando Collor was born into a political family. He is the son of the former Senator Arnon Affonso de Farias Mello and Leda Collor (daughter of former Labour Minister Lindolfo Collor), led by his father, former governor of Alagoas and proprietor of the Arnon de Mello Organization, the branch of Rede Globo in the state. "Collor" is a Portuguese adaptation of the German surname Koehler, from his maternal grandfather Lindolfo Leopoldo Boeckel Collor.

Collor has served as Senator for Alagoas since February 2007, having been first elected in 2006 and reelected in 2014.

Early career

Collor became the president of Brazilian football club Centro Sportivo Alagoano (CSA) in 1976. After entering politics, he was successively named mayor of Alagoas' capital Maceió in 1979 (National Renewal Alliance Party), elected a federal deputy (Democratic Social Party) in 1982, and eventually elected governor of the small Northeastern state of Alagoas (Brazilian Democratic Movement Party) in 1986.

During his term as governor, he attracted a lot of publicity by allegedly fighting the payment of super-salaries to public servants, whom he labeled marajás (maharajas)[2] (likening them to the former princes of India who received a stipend from the government as compensation for relinquishing their lands). The efficacy of his policies in reducing public expense is disputed, but it certainly made him popular over the country.[3] This helped boost his political career, with the help of television appearances in nationwide broadcasts (quite unusual for a governor from such a small state).

Presidency

In 1989 Collor defeated Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in a controversial two-round presidential race and 35 million votes. In December 1989, days prior to the second round, businessman Abílio Diniz was the victim of a sensational political kidnapping. The act is recognized as an attempt to sabotage Lula's chances of victory.[4] by associating the kidnapping with the left wing. At the time, Brazilian law barred any party from addressing the media on the days prior to election day. Lula's party thus had no opportunity to clarify the accusations that the party (PT) was involved in the kidnapping. Collor won in the state of São Paulo against many prominent political figures.[5] The first popularly elected President of Brazil in 29 years, Collor spent the early years of his government allegedly battling inflation, which at times reached rates of 25% per month.

The very day he took office, Collor launched the Plano Collor (Collor Plan), implemented by his finance minister Zélia Cardoso de Mello (not related to Collor). The Plan attempted to reduce the money supply by forcibly converting large portions of consumer bank accounts into non-cashable government bonds, while at the same time increasing the printing of money bills, a contradictory measure to combat hyper-inflation.[6]

Free trade, privatization and state reforms

Under Zélia's tenure, Brazil had a period of major changes, featuring what ISTOÉ magazine called an "unprecedented" "revolution"[7] in many levels of public administration: "privatization, opening its market to free trade, encouraging industrial modernization, temporary control of the hyper-inflation and public debt reduction."[8]

In the month before Collor took power, hyperinflation was 25 percent per month and growing. All accounts over 50,000 Cruzeiros (about US$500 at that time), were frozen for several weeks. He also proposed freezes in wages and prices, as well as major cuts in government spending. The measures were received unenthusiastically by the people, though many felt that radical measures were necessary to kill the hyperinflation. Within a few months, however, inflation resumed, eventually reaching rates of 10 percent per month.

During the course of his government, Collor was accused of condoning an influence peddling scheme. The accusations weighed on the government and they led Collor and his team to an institutional crisis leading to a loss of credibility that reached the finance minister, Zélia.[7]

This political crisis had negative consequences on his ability to carry out his policies and reforms.[9] The Plano Collor I, under Zélia would be renewed with the implementation of the Plano Collor II; the government's loss of prestige would make that follow-up plan short-lived and largely ineffective.[8] The failure of Zélia and Plano Collor I led to their substitution by Marcílio Marques Moreira and his Plano Collor II. Moreira's plan tried to correct some aspects of the first plan, but it was too late. Collor's administration was paralyzed by the fast deterioration of his image, through a succession of corruption accusations.[10]

During the Plano Collor, yearly inflation was at first reduced from 30,000 percent in 1990 (Collor's first year in government) to 400 percent in 1991, then climbing to 1,020 percent in 1992 (when he left office).[11] Inflation continued to rise to 2,294 percent in 1994 (two years after he left office).[12]

Although Zélia acknowledged later that the Plano Collor didn't end inflation, she also stated: "It is also possible to see with clarity that, under very difficult conditions, we promoted the balancing of the national debt – and that, together with the commercial opening, it created the basis for the implementation of the Plano Real."[7]

Part of Collor's more conservative program was followed by his successors:[13] Itamar Franco, Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Lula da Silva.[14] Collor's administration privatized 15 different companies (including Acesita), and began the process of privatization for others, such as Embraer, Telebrás and Companhia Vale do Rio Doce.[8] Some members of Collor's government were also part of the later Cardoso administration in different or similar functions: Pedro Malan, Renan Calheiros (PMDB-AL); Antônio Kandir (PSDB-SP); Pratini de Moraes and Celso Lafer; Reinhold Stephanes, Armínio Fraga; Pedro Parente.

Luiz Carlos Bresser-Pereira, a minister in the previous Sarney and the following Fernando Henrique Cardoso administrations, stated that "Collor changed the political agenda in the country, because implemented brave and very necessary reforms, and he pursued fiscal adjustments. Although other attempts had been made since 1987, it was during Collor's administration that old statist ideas were confronted and combated (...) by a brave agenda of economic reforms geared towards free trade and privatization."[15] According to Philippe Faucher, professor of political science at McGill University,[16] the combination of the political crisis and the hyperinflation continued to decrease Collor's credibility and in that political vacuum an impeachment process took place, precipitated by Pedro Collor's (Fernando Collor's brother) accusations and other social and political sectors which thought would be harmed by his policies.[8]

Awards

In 1991, UNICEF chose three health programs: Community Agents, Lay Midwives and Eradication of measles as the best in the world. These programs were promoted during Collor's administration. Until 1989, the Brazilian vaccination record, was considered the worst in South America. During Collor's administration, Brazil's vaccination program won a United Nations prize, as the best in South America. Collor's project Minha Gente (My People) won the UN award Project Model for the Humanity in 1993.

Corruption charges and impeachment

.jpg)

In May 1992, Fernando Collor was accused by his brother, Pedro Collor, of condoning an influence peddling scheme run by his campaign treasurer, Paulo César Farias. The Federal Police and the Federal Prosecution Service began an investigation soon after. On July 1, 1992, a Joint Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry, composed of Senators and members of the Chamber of Deputies, was formed in Congress to conduct an investigation on the accusation made by Pedro Collor, and to review the evidence uncovered by the police and the federal prosecutors. Senator Amir Lando was chosen as the Rapporteur of the Commission of Inquiry, chaired by Congressman Benito Gama. Farias, Pedro Collor, government officials and other people of interest to the investigation were subpoenaed to the Commission and gave depositions before it. Some weeks later, with the investigation progressing and under fire, President Fernando Collor went on national television to ask for the people's support by going out on the street and protesting against "coup" forces. On August 11, 1992, thousands of students organized by the National Student Union (União Nacional dos Estudantes – UNE), protested on the streets against Collor. Their faces, often painted in a mixture of the colors of the flag and protest-black, lead to them being called "Caras-pintadas" ("Painted Faces").[17]

On August 26, 1992, the final congressional inquiry report was released; the conclusions of the Rapporteur, Senator Amir Lando, were approved by 16 of the Commission's 21 members, with 5 votes against the report; the report concluded that there was proof that Fernando Collor had personal expenses paid for by money raised by Paulo César Farias through his influence peddling scheme.

As a result of this report, a petition was presented to the Chamber of Deputies by citizens Barbosa Lima Sobrinho and Marcelo Lavenère Machado, respectively the then President of the Brazilian Press Association and the then President of the Brazilian Bar Association, formally accusing President Collor of having committed crimes of responsibility (the Brazilian equivalent of "high crimes and misdemeanors") warranting removal from office per the constitutional and legal norms regulating impeachment proceedings. In Brazil, the formal petition asking for the impeachment of the President needs to be submitted by citizens, not by corporations or public institutions. On that formal petition, submitted on September 1, 1992, impeachment proceedings were initiated in the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of Congress. A special committee of the Chamber of Deputies was constituted on September 3, 1992 to study the impeachment petition. On September 24, 1992, the committee voted (32 votes in favour, one vote against, one abstention) to approve a report accepting the impeachment petition and recommending that the full Chamber of Deputies should accept the charges of impeachment. Under the Constitution of Brazil, the impeachment process would only proceed if two thirds of the Chamber of Deputies voted to allow the charges of impeachment to be presented to the Senate. On September 29, 1992, Collor was impeached by the Chamber of Deputies, with more than two thirds of its members concurring. In the decisive roll call vote, 441 deputies voted for and 38 deputies voted against the admission of the charges of impeachment.[18]

In the morning of September 30, 1992, the accusation against the President was formally passed from the Chamber of Deputies to the Senate, and the proceedings for the trial of impeachment were initiated in the Upper House of Congress. Later on the same day, a Committee of the Senate was formed to examine the case file and decide on how to proceed. This Committee's remit was only to examine if all legal formalities had been followed, and not to examine the merits of the case. Still on the same date, the Committee issued its report, recognizing that the charges of impeachment had been presented in accordance with the Constitution and the Laws, and proposing therefore that the Senate should organize itself into a Court of Impeachment and conduct the trial of the President. In the morning of October 1, 1992, this report was presented on the floor of the Senate, and the full Senate voted to accept it and to proceed accordingly. On the same day the then President of the Federal Supreme Court, Justice Sydney Sanches, was notified of the opening of the trial process in the Senate, and, in accordance with the Constitution, he began to preside over the acts of the process. His first act was to order the notification of the defendant. On October 2, 1992, President Collor received a formal summons from the Brazilian Senate notifying him that the Senate had accepted the report, and that he was now a defendant in an impeachment trial. Per the Constitution of Brazil, upon receipt of that writ of summons, Collor's presidential powers were suspended for 180 days, and Vice President Itamar Franco became Acting President. The Senate also sent an official communication to the office of the Vice-President on the same day, to formally acquaint him of the suspension of the President, and to give him notice that he was now the Acting President.

By the end of December, it was obvious that Collor would be convicted and removed from office by the Senate. In hopes of staving this off, Collor resigned on December 29, 1992 on the last day of the proceedings. Collor's resignation letter was read by his attorney in the floor of the Senate, and the impeachment trial was adjourned so that the Congress could meet in joint session, first to take formal notice of the resignation and proclaim the office of President vacant, and then to swear in Franco as President in his own right.

However, later on the same day, after Collor's resignation took effect and Franco was sworn in, the Senate resumed its sitting as a Court of impeachment with the President of the Supreme Court as the Senate's presiding officer. Collor's attorneys argued that with Collor's resignation, the impeachment trial could not proceed and should have been closed without a ruling on the merits. The attorneys arguing for Collor's removal, however, argued that the trial should continue, with a view to determining whether or not the defendant should face the constitutional penalty of suspension of political rights for eight years. The Senate voted to continue the trial. It ruled that, although the possible penalty of removal from office had been rendered moot, the determination of the former President's guilt or innocence was still relevant because a conviction on changes of impeachment would carry with it a disqualification from holding public office for eight years. The Senate found that, since the trial had already started, the defendant could not use his right to resign the presidency as a means to avoid a ruling on the merits of the case.

Later, in the early hours of December 30, 1992, by the required two-thirds majority, the Senate found the former President guilty of the charges of impeachment. Of the 81 members of the Senate, 79 took part in the final vote: 76 Senators voted to convict the former President, and 3 voted to acquit him. The penalty of removal from office was not imposed as Collor had already resigned, but as a result of his conviction the Senate barred Collor from holding public office for eight years. After the decisive vote, the Senate concluded its actions as a Court of Impeachment by issuing a formal written Court opinion summarizing the conclusions and orders resulting from the judgement, as required by Brazilian Law. The Senate's formal written sentence on the impeachment trial, containing its ruling on the conviction of the former President and on the imposition of the penalty of disqualification from holding public office for eight years, signed by the President of the Supreme Court and by the Senators on December 30, 1992, was published in the Diário Oficial da União (the Brazilian Federal Government's official journal) on December 31, 1992.[19]

In 1993, Collor challenged before the Brazilian Supreme Court the Senate's decision to continue the trial after his resignation but the Supreme Court ruled the Senate's action valid.

In 1994, the Supreme Court tried the ordinary criminal charges stemming from the Farias corruption affair; the ordinary criminal accusation was presented by the Brazilian federal prosecution service (Ministério Público Federal). The Supreme Court had original jurisdiction under the Brazilian Constitution because Collor was one of the defendants and the charges mentioned crimes committed by a President while in office. If found guilty of the charges, the former President would face a jail sentence.[20] However, Collor was found not guilty. The Federal Supreme Court threw out the charges of corruption against him on a technicality,[20] citing a lack of evidence linking Collor to Farias' influence-peddling scheme. A key piece of evidence, Paulo César Farias' personal computer, was found to be inadmissable as it has been obtained during an illegal police search conducted without a prior search and seizure warrant.[21] Other pieces of evidence that were only gathered as a consequence of the information first extracted from files stored in Farias' computer were also voided, as the Collor legal defense team successfully invoked the fruit of the poisonous tree doctrine before the Brazilian Supreme Court, so that the evidence that was only gathered as a consequence of the illegally obtained information was also struck from the record.

After his acquittal in the criminal trial, Collor again attempted to void the suspension of his political rights imposed by the Senate, without success, as the Supreme Court ruled that the judicial trial of the ordinary criminal charges and the political trial of the charges of impeachment were independent spheres. Collor thus only regained his political rights in 2000, after the expiration of the eight year disqualification imposed by the Brazilian Senate.

Collor's version of the impeachment

For several years after his removal from office, Collor maintained a website which has since been taken offline. In discussing the events surrounding the corruption charges, the former website stated: "After two and half years of the most intense investigation in Brazilian history, the Supreme Court of Brazil declared him innocent of all charges. Today he is the only politician in Brazil to have an officially clear record validated by an investigation by all interests and sectors of the opposition government. Furthermore, President Fernando Collor signed the initial document authorizing the investigation."[22]

Post-presidency

.jpg)

In 2000, Collor tried to run for mayor of São Paulo. His candidacy was declared invalid by the electoral authorities, as his political rights were still suspended by the filing deadline.[23]

In 2002, with political rights restored, he ran for Governor of Alagoas, but lost to incumbent Governor Ronaldo Lessa, who was seeking reelection.[24]

In 2006, Collor was elected to the Brazilian Senate representing his state of Alagoas, with 44.03% of the vote, running again against Lessa.[25] Collor has been, since March 2009, a Chairman of the Senate Infrastructure Commission.

Collor ran again for Governor of Alagoas in 2010.[26] However, he lost the race, finishing narrow third after Lessa and an incumbent Teotonio Vilela Filho, thus getting eliminated from a runoff. This was Collor's second electoral loss.

In 2014, Collor was reelected to the Senate with 55% of the vote.[27]

On August 20, 2015, Collor was charged by the Prosecutor General of Brazil for corruption, as a development of Operation Car Wash (Portuguese: Operação Lava Jato). Details of the charge have been kept under wraps so as not to jeopardize the investigation.[28]

Honour

Foreign honour

-

Malaysia : Honorary Recipient of the Order of the Crown of the Realm (1991)[29]

Malaysia : Honorary Recipient of the Order of the Crown of the Realm (1991)[29]

References

- ↑ "Fernando Afonso Collor de Mello - Biografia". UOL Educação.

- ↑ Solingen, Etel (1998). Regional Orders at Century's Dawn. p. 147.

- ↑ Bezerra, Ada Kesea Guedes; Silva, Fábio Ronaldo. "O marketing político e a importância da imagem-marca em campanhas eleitorais majoritárias" (PDF). Biblioteca On-line de Ciências da Comunicação (in Portuguese).

- ↑ Chauí, Marilena (October 29, 2010). "Um alerta". Carta Maior. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- ↑ Lattman-Weltman, Fernando. "29 de Setembro de 1992: o impeachment do Collor" [September 29, 1992: the impeachment of Collor]. Centro de Pesquisa e Documentação de História Contemporânea do Brasil. Archived from the original on August 14, 2007.

- ↑ "A História do Plano Collor" [The History of the Collor Plan]. sociedadedigital.com.br. Archived from the original on November 28, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Zélia está voltando" [Zélia is returning]. ISTOÉ Dinheiro. October 25, 2006. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Revista Brasileira de Economia – Os efeitos da privatização sobre o desempenho econômico e financeiro das empresas privatizadas". scielo.br.

- ↑ "unopec.com.br" (PDF). unopec.com.br.

- ↑ Archived December 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "The Hyperinflation in Brazil, 1980–1994". sjsu.edu.

- ↑ http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+br0009

- ↑ Pimenta, Angela (June 27, 2006). "Lula segue política econômica de FHC, diz diretor do FMI". BBC Brasil. British Broadcasting Corporation.

- ↑ A CONTINUIDADE DA POLÍTICA MACROECONÔMICA ENTRE O GOVERNO CARDOSO E O GOVERNO LULA: UMA ABORDAGEM SÓCIO-POLÍTICA

- ↑ Silvando da Silva do Nascimento, Rangel. A POLÍTICA ECONÔMICA EXTERNA DO GOVERNO COLLOR: LIBERALIZAÇÃO COMERCIAL E FINANCEIRA. Retrieved August 30, 2007.

- ↑ "Philippe Faucher". McGill University. Archived from the original on January 15, 2008.

- ↑ Rezende, Tatiana Matos. "UNE 70 Anos: "Fora Collor: o grito da juventude cara-pintada"". União Nacional dos Estudantes. Archived from the original on September 3, 2007. Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- ↑ Lattman-Weltman, Fernando. September 29, 1992: Collor's Impeachment Archived August 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.(in Portuguese) Fundação Getúlio Vargas. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ↑ Imprensa Nacional – Visualização dos Jornais Oficiais. In.gov.br (December 31, 1992). Retrieved on August 12, 2013.

- 1 2 "Fernando Collor é eleito senador por Alagoas". O Globo. Grupo Globo. October 1, 2006.

- ↑ "Como foi a ação contra Collor". O Globo. Grupo Globo. April 18, 2006. Archived from the original on November 19, 2007 – via Senado Federal.

- ↑ Did You Know? Archived December 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Percival Albano Nogueira Junior, José. Sentença de indeferimento do registro da candidatura de Fernando Collor à Prefeitura de São Paulo Jus Navigandi. August 4, 2000. Retrieved on August 18, 2007.

- ↑ Simas Filho, Mário (September 13, 2006). "Elle Voltou". ISTOÉ. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ↑ "Após 14 anos de sua renúncia, Collor volta a Brasília como senador". Folha de S.Paulo. October 10, 2006. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ↑ "Fernando Collor confirma pré-candidatura ao governo de Alagoas". O Globo. Grupo Globo. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ↑ "Fernando Collor, PTB, é reeleito senador pelo estado de Alagoas". G1. Grupo Globo. October 5, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Brazil House Leader, Ex-President Hit With Corruption Charges". The New York Times. August 20, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Senarai Penuh Penerima Darjah Kebesaran, Bintang dan Pingat Persekutuan Tahun 1991." (PDF).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fernando Collor. |

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by José de Medeiros Tavares |

Governor of Alagoas 1987–1989 |

Succeeded by Moacir Lopes de Andrade |

| Preceded by José Sarney |

32nd President of Brazil March 15, 1990 – December 29, 1992 Itamar Franco Acting President: October 2 – December 29, 1992 |

Succeeded by Itamar Franco |