Collegiate Gothic

Collegiate Gothic was an architectural style subgenre of Gothic Revival architecture, popular in the late-19th and early-20th centuries for college and high school buildings in the United States and Canada, and to a certain extent Europe. A form of historicist architecture, it took its inspiration from English Tudor and Gothic buildings.

Ralph Adams Cram, arguably the leading Gothic Revival architect and theoretician in the early 20th Century, stated the appeal of the Gothic for educational facilities in his book Gothic Quest as, "Through architecture and its allied arts we have the power to bend men and sway them as few have who depended on the spoken word. It is for us, as part of our duty as our highest privilege to act ... for spreading what is true."[1]

History

Beginnings

Gothic Revival architecture was used for American college buildings as early as 1829, when "Old Kenyon" was completed on the campus of Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio.[2] Alexander Jackson Davis's University Hall (1833–37, demolished 1890), on New York University's Washington Square campus, was another early example. Richard Bond's church-like library for Harvard College, Gore Hall (1837–41, demolished 1913), became the model for other library buildings.[3][4] James Renwick, Jr.'s Free Academy Building (1847–49, demolished 1928), for what is today City College of New York, continued in the style. Inspired by London's Hampton Court Palace, Swedish-born Charles Ulricson designed Old Main (1856–57) at Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois.[5]

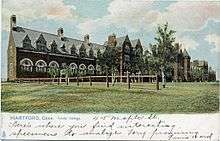

Following the Civil War, idiosyncratic High Victorian Gothic buildings were added to the campuses of American colleges, including Yale College – Farnam Hall (1869–70), Russell Sturgis, architect; the University of Pennsylvania – College Hall (1870–72), Thomas W. Richards, architect; Harvard College – Memorial Hall, (1870–77), William Robert Ware and Henry Van Brunt, architects; and Cornell University – Sage Hall (1871–75), Charles Babcock, architect. In 1871, English architect William Burges designed a row of vigorous French Gothic-inspired buildings for Trinity College – Seabury Hall, Northam Tower, Jarvis Hall (all completed 1878) – in Hartford, Connecticut.

Tastes became more conservative in the 1880s, and "collegiate architecture soon after came to prefer a more scholarly and less restless Gothic."[6]

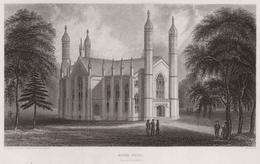

"Old Kenyon" (1827–29), Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio. Architect Charles Bullfinch designed its steeple.

"Old Kenyon" (1827–29), Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio. Architect Charles Bullfinch designed its steeple. University Hall (1833–37), New York University, Alexander Jackson Davis, architect.

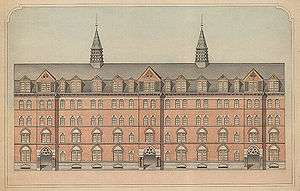

University Hall (1833–37), New York University, Alexander Jackson Davis, architect.

Free Academy Building (1847–49), City College of New York, James Renwick, Jr., architect.

Free Academy Building (1847–49), City College of New York, James Renwick, Jr., architect.

Original design for Farnam Hall (1869), Yale University, Russell Sturgis, architect.

Original design for Farnam Hall (1869), Yale University, Russell Sturgis, architect.- College Hall (1870–72), University of Pennsylvania, Thomas W. Richards, architect.

.tiff.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Movement

Beginning in the late-1880s, Philadelphia architects Walter Cope and John Stewardson expanded the campus of Bryn Mawr College in an understated English Gothic style that was highly sensitive to site and materials. Inspired by the architecture of Oxford and Cambridge universities, and historicists but not literal copyists, Cope & Stewardson were highly influential in establishing the Collegiate Gothic style.[8] Commissions followed for collections of buildings at the University of Pennsylvania (1895–1911), Princeton University (1896–1902), and Washington University in St. Louis (1899–1909), marking the nascent beginnings of a movement that transformed many college campuses across the country.

In 1901, the firm of Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge created a master plan for a Collegiate Gothic campus for the fledgling University of Chicago, then spent the next 15 years completing it. Some of their works, such as the Mitchell Tower (1901–1908), were near-literal copies of historic buildings.

George Browne Post designed the City College of New York's new campus (1903–1907) at Hamilton Heights, Manhattan, in the style.

The style was experienced up-close by a wide audience at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri. The World's Fair and 1904 Olympic Games were held on the newly completed campus of Washington University, which delayed occupying its buildings until 1905.

The movement gained further momentum when Charles Donagh Maginnis designed Gasson Hall at Boston College in 1908. Maginnis & Walsh went on to design Collegiate Gothic buildings at some twenty-five other campuses, including the main buildings at Emmanuel College (Massachusetts), and the law school at the University of Notre Dame.

Ralph Adams Cram designed one of the most poetic collections of Collegiate Gothic buildings for the Princeton University Graduate College (1911–1917).

James Gamble Rogers's extensive work at Yale University, beginning in 1917, took historicist fantasy to an extreme. He was criticized by the growing Modernist movement.[9] His cathedral-like Sterling Memorial Library (1927–30), with its ecclesiastical imagery and lavish use of ornament, came under vocal attack from one of Yale's own undergraduates:

"A modern building constructed for purely modern needs has no excuse for going off in an orgy of meretricious medievalism and stale iconography."[10]

Following McMaster University's decision to relocate to Hamilton, Ontario, Canadian architect William Lyon Somerville designed its new campus (1928–30) in the style.

The first occurrence of the term "Collegiate Gothic" in literature was made by architect Charles Klauder in his book College Architecture in America (1929): "The architectural vicissitudes through which the separate units or colleges on the Don and Cam have passed, such as the addition of stories, the completion of quads, the addition of wall dormers and the like, only confirm the claim of adaptability and elasticity for this, the Collegiate Gothic style."[11]

1904 commentary

In his praise for Cope & Stewardson's Quadrangle Dormitories at the University of Pennsylvania, architect Ralph Adams Cram revealed some of the racial and cultural implications underlying the Collegiate Gothic:

It was, of course, in the great group of dormitories for the University of Pennsylvania that Cope and Stewardson first came before the entire country as the great exponents of architectural poetry and of the importance of historical continuity and the connotation of scholasticism. These buildings are among the most remarkable yet built in America ...

First of all, let it be said at once that primarily they are what they should be: scholastic in inspiration and effect, and scholastic of the type that is ours by inheritance; of Oxford and Cambridge, not of Padua or Wittenberg or Paris. They are picturesque also, even dramatic; they are altogether wonderful in mass and in composition. If they are not a constant inspiration to those who dwell within their walls or pass through their "quads" or their vaulted archways, it is not their fault but that of the men themselves.

The [Spanish-American War Memorial] tower has been severely criticized as an archaeological abstraction reared to commemorate contemporary American heroism. The criticism seems just to me, though only in a measure. American heroism harks back to English heroism; the blood shed before Manila and on San Juan Hill was the same blood that flowed at Bosworth Field, Flodden, and the Boyne. Therefore the British base of the design is indispensable, for such were the racial foundations.[12]

Hybrids

Collegiate Gothic complexes were most often horizontal compositions, save for a single tower or towers serving as an exclamation.

At the University of Pittsburgh, Charles Klauder was presented with a limited site and opted for verticality. The Cathedral of Learning (1926–37), a steel-frame, limestone-clad, 42-story skyscraper, is the world's second tallest university building and second tallest Gothic-styled building.[7] It has been described as the literal culmination of late Gothic Revival architecture.[13] The tower contain a half-acre Gothic hall whose mass is supported only by its 52-foot (16 m) tall arches.[14] It is accompanied by the campus's other Gothic Revival structures by Klauder, including the Stephen Foster Memorial (1935–1937) and the French Gothic Heinz Memorial Chapel (1933–1938).

Architects of the Collegiate Gothic style

Examples

- Altgeld's castles – a set of buildings within five Illinois universities (1896–1899)

- Augustana College (Illinois), Rock Island, Illinois – The Old Seminary, the Ascension Chapel, and Founders Hall (1923)

- Berry College – Ford buildings

- Boston College – specifically Gasson Hall, Devlin Hall, St. Mary's Hall, and Bapst/Burns Library

- Bryn Athyn Cathedral of Bryn Athyn College

- Bryn Mawr College – Pembroke Hall (1894)[15]

- Carleton College

- Central Commerce Collegiate, Toronto

- Central Technical School, Toronto

- City College of New York (1903), George Browne Post, architect

- College of Wooster – Kauke Hall

- Columbia University: Teachers College

- Cornell University

- Danforth Collegiate and Technical Institute, Toronto 1922–1923

- Duke University – Duke Chapel (1930–1935), and West Campus, arch.

- Eastern Commerce Collegiate Institute, Toronto, Canada 1925

- Eastern Senior High School (1923), Washington, D.C.[16]

- Emma Willard School

- Florida A&M University

- Florida State University

- Fordham University – Rose Hill Campus[17][18]

- Fordson High School, Dearborn, Michigan

- Franklin & Marshall College – Old Main, Goethean Hall, and Diagnothian Hall (1854–1857)

- Grinnell College

- High Point Central High School (1926), (High Point, North Carolina)

- Hillsborough High School (Tampa, Florida)

- Indiana University-Bloomington

- Isaac E. Young Middle School, New Rochelle, New York

- John Carroll University

- John Marshall High School, Los Angeles, California

- Kenyon College

- Knox College – Old Main (1857)[5]

- Lehigh University

- Loyola University Maryland

- Loyola University New Orleans – Marquette Hall (1910)

- McGill University, Montreal, Canada

- McKinley High School, St. Louis, Missouri

- McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

- The Mary Louis Academy, Jamaica Estates, New York (1937)

- Michigan State University

- Milliken Public School, Markham – façade only (1929)

- New Jersey Institute of Technology – Central King Building, the old Central High School of Newark (1911)

- North Toronto Collegiate Institute 1912 – demolished

- Northwestern University

- Northwest Missouri State University – Administration Building

- Oglethorpe University, Atlanta, Georgia

- Parkdale Collegiate Institute, Toronto 1929

- Princeton University – Blair Hall (1896)[19]

- R. H. King Academy, Toronto – destroyed in fire and only arch from girls' entrance from original building remains (1922)

- Reed College, Oregon

- Rhodes College, Memphis, Tennessee

- Purdue University

- St. Joseph University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania[20]

- Sewanee: The University of the South, Sewanee, Tennessee

- Trinity College, Connecticut

- United States Military Academy, West Point, New York

- University of Arkansas

- University of Chicago

- University of Denver

- University of Florida

- University of Idaho

- University of Iowa

- University of Michigan – U of M Law School (1924), Martha Cook Building (1915)

- University of Notre Dame

- University of Oklahoma

- University of Pennsylvania – Quadrangle Dormitories (1894–1911),[21] Medical School (1904, 1928), Veterinary School and Hospital (1906, 1912), Law School (1900)

- University of Pittsburgh (Cathedral of Learning, Heinz Chapel, Stephen Foster Memorial, Clapp Hall)

- University of Richmond, Virginia

- University of St. Thomas, Minnesota

- University of Saskatchewan, Canada

- University of Southern California – Wallis Annenberg Hall

- University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

- University of Toledo – University Hall and Memorial Field House, Ohio

- University of Toronto – St. George campus, Canada

- University of Washington in Seattle – Suzzallo Library (1926)

- The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada

- Washington University in St. Louis – Brookings Hall (1900), and the Danforth Campus

- Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

- West Chester University

- Western Technical-Commercial School, Toronto (1927)

- Williams College, Thompson Memorial Chapel

- Yale University – Sterling Memorial Library, Harkness Tower, and the Memorial Quadrangle; arch. James Gamble Rogers.

- York Memorial Collegiate Institute, Toronto (1929)

See also

References

- ↑ Slipek, Jr., Edwin J., Ralph Adams Cram, The University of Richmond and the Gothic Style Today, Marsh Art Gallery, University of Richmond, 1997 p.19

- ↑ Rev. Norman Nash designed the building. Architect Charles Bullfinch was asked to review the plans, and designed the steeple. Marjorie Warvelle Harbaugh, "Charles Bullfinch," The First Forty Years of Washington DC Architecture, (Lulu, 2013), p. 362.

- ↑ Daniel Coit Gilman, "The Library of Yale College," The University Quarterly (October 1860), p. 9.

- ↑ Kenneth A. Breisch, Henry Hobson Richardson and the Small Public Library in America, (MIT Press, 1997), p. 60.

- 1 2 "Old Main". Knox College. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ↑ Lewis, The Gothic Revival, p. 185.

- 1 2 "Cathedral of Learning, Pittsburgh". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ↑ "Collegiate Gothic". Bryn Mawr Library.

- ↑ Paul Goldberger, "The Sterling Library: A Reassessment," On the Rise: Architecture and Design in a Post Modern Age, (Penguin Books, 1985), pp. 269–71.

- ↑ William Harlan Hale, "Yale's Cathedral Orgy," The Nation (April 29, 1931), pp. 471–72.

- ↑ Klauder, Charles Z.; Wise, Herbert C. (1929). College Architecture in America: And Its Part in the Development of the Campus. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. p. 44.

- ↑ Ralph Adams Cram, “The Work of Messrs. Cope and Stewardson,” The Architectural Record, vol. XVI, no. 5 (November 1904), pp. 414–15, 417.

- ↑ Trump, James D. (1975-08-25). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form: Cathedral of Learning" (PDF). Pennsylvania's Historic Architecture & Archaeology. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

"...in the literal sense of the word, Late Gothic Revival architecture culminated in the University of Pittsburgh's skyscraping Cathedral of Learning". Marcus Whiffen, architecture historian

- ↑ Toker, Franklin (2009). Pittsburgh: A New Portrait. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 327. ISBN 0-8229-4371-9.

- ↑ "Collegiate Gothic – Cope and Stewardson". Bryn Mawr College Library Special Collections. 2001. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Replace or Modernize? The Future of the District of Columbia's Endangered Old and Historic Public Schools: Eastern Senior High School" (PDF). 21st Century School Fund. May 2001. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ↑ Venturi, Dan. "Fordham University Church". Fordham University. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ↑ Jacobs, Peter (October 11, 2013). "Tour Fordham University's Stunning Campus In The Bronx". Business Insider. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Orange Key Virtual Tour: Blair Hall". Princeton University. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ↑ "History of SJU | Saint Joseph's University". www.sju.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- ↑ "Virtual Tour of Penn's Campus: The Quadrangle". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on September 24, 2005. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Collegiate Gothic architecture in the United States. |

Sources

- Lewis, Michael J., The Gothic Revival (London: Thames & Johnson Ltd., 2002). ISBN 0-500-20359-8