William Hope Harvey

| William Hope Harvey | |

|---|---|

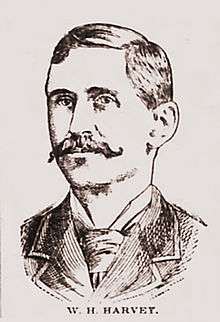

W.H. Harvey in 1895 | |

| Born |

August 16, 1851 Buffalo, Virginia |

| Died |

February 11, 1936 (aged 84) Monte Ne, Benton County, Arkansas |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | "Coin" Harvey |

| Occupation | lawyer, political activist |

| Known for | "free silver" political activism |

.jpg)

William Hope "Coin" Harvey (August 16, 1851 – February 11, 1936) was an American lawyer, author, politician, and health resort owner best remembered as a prominent public intellectual advancing the idea of monetary bimetallism. His enthusiasm for the use of silver as legal tender was later incorporated into the platforms of both the People's Party and the Democratic Party in the early 1890s. Harvey was also the founder of the short-lived Liberty Party and that party's nominee for President of the United States in 1932.

Biography

Early years

William Hope Harvey was born on August 16, 1851 on a farm near the small town of Buffalo, Virginia (later West Virginia).[1] He was the fifth child of six born to Robert and Anna Harvey. His father, Robert Trigg Harvey, was a Virginian of Scottish and English ancestry, and his mother, who had Virginian ancestors traceable to colonial times, was descended from French ancestors who had long since peopled the territory around nearby Gallipolis, Ohio.

Harvey was educated in local public schools before attending the Buffalo Academy from 1865 to 1867.[1] At the end of his time there, still just 16 years old, he taught school for three months before enrolling at Marshall College in Guyandotte, Virginia. He remained there only three months before leaving to briefly teach school again. This ended his formal education, although he continued to study law, ultimately managing to gain admission to the West Virginia state bar.

Legal career

After gaining his license to practice law, Harvey opened up a law practice in Barboursville, West Virginia, which proved to be a relatively successful operation. He had a good court appearance being slender, five foot ten, erect bearing and penetrating blue eyes. He was soon practicing law in Illinois and Ohio.

Early in his career, he took a case that no other attorney would. He defended a white man who married an African American woman, which was against the law in West Virginia. To close his defense Harvey asked, "Can anyone in this courtroom prove that this man has not a drop of colored blood in his veins." The case was dismissed.

Three years after opening his law practice, Harvey moved to Huntington, West Virginia and became law partners with his brother Thomas. Then in 1873 he moved forty miles to Gallipolis. Here he met Anna Halliday and they were married June 26, 1876. Later that year they moved to Cleveland. While they were living there they had two children.

In 1879 the family moved to Chicago where they had a third child. Finally in 1881 the Harveys returned to Gallipolis, where W.H. worked as an attorney for several wholesale firms in the area.[2] Harvey left the legal profession in 1884, ostensibly for reasons of health, and moved west to Colorado to work as a miner and buy and sell real estate.[2]

Populist political activist

It was during his time in Colorado that Harvey became exposed to the idea that the demonetization of silver through passage of the Coinage Act of 1873 had extremely deleterious economic effects on the American economy, including the multiyear Long Depression of 1873 to 1879, the Depression of 1882 to 1885, recessions in 1887 and 1890, and the Panic of 1893. This entire era was marked by general deflation, tight money supply, mass bankruptcies, and unemployment, which many attributed to a lack of sufficient circulating currency to support the needs of industry and commerce.[1]

Harvey became a leading advocate of a return to the unlimited coinage of silver into money, and in 1894 authored a popular pamphlet to advance this policy, Coin's Financial School, which became an important ideological document of the nascent Populist movement. The massive circulation of this work made Harvey a public figure as one of the leading free silver advocates in America.[1]

Other populist writings followed, including the books A Tale of Two Nations (1894), The Money of the People (1895), The Patriots (1895) and a sequel to his popular 1894 work, Coin on Money, Trusts, and Imperialism (1899). Harvey also appeared in public debates, assuming a leading place as public advocate for the idea of a return to bimetallism.

In 1895 Harvey formed his own political organization, an agitational society known as the Patriots of America.[3] The Chicago-based organization was dedicated to advancing the ideas of direct legislation and free coinage of silver through the supplying of inserts and stereographic plates on the topic to newspapers around the country.[4]

Harvey took for himself the title of "First National Patriot" as the leader of the Patriots of America organization.[5] In 1898 group claimed an implausibly large network of 250 local lodges and a circulation of 30,000 for its official organ, The Patriots' Bulletin,[5] a weekly which was originally published as The National Bimetallist.[3]

Harvey was also active in campaigning for staunch free silver advocate William Jennings Bryan in Arkansas in the election of 1896.[1] The 1896 campaign, which involved fusion of the People's Party with the Democratic Party proved catastrophic to the former organization, resulting in its widespread disintegration in the wake of Bryan's defeat.

Resort founder

In 1900, Harvey turned away from politics to the world of business, purchasing land five miles outside of Rogers, Arkansas with a view to building a health resort on the site.[1] Harvey named the site “Monte Ne,” which he claimed derived from the Spanish and Native American words for “mountain” and “water.”[1] He built a hotel there in May 1901, expanding the operation to include two additional hotels, a tennis court, and the first indoor swimming pool in Arkansas in succeeding years.[1]

Harvey constructed a railroad spur line to connect his resort with line of the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad.[1] In 1913 he also established the Ozark Trails Association to promote good roads, highway markers, and maps throughout the southwest.[1]

In his later years, as Monte Ne began to sink into debt and his health began deteriorating, he believed that human civilization was on the verge of collapse. He began making plans to build a giant obelisk, although he referred to it as 'The Pyramid'. It was to serve as a time capsule for future humans to see what society had been like at its peak.

Although some preliminary work on the Pyramid was done, Harvey became preoccupied with building an amphitheater which used up most of his funds and after the stock market crash of 1929 all work at Monte Ne ceased and the Pyramid was never constructed.

Liberty Party and 1932 presidential election

In 1932 Harvey formed the Liberty Party based on his financial theories and headed that party's ticket as candidate for President of the United States in the election of 1932. He polled around 53,000 votes to finish fifth overall, with 0.13% of the national tally. However, 30,000 of his votes came in the state of Washington alone, where he finished in third place with 4.93% of the statewide vote.[1]

Death and legacy

W.H. Harvey died February 11, 1936 at Monte Ne in Benton County, Arkansas.[1] He was 84 years old at the time of his death.

Harvey's home in Huntington, West Virginia, commonly known as the Coin Harvey House, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Gaye, Bland, "'Coin' Harvey (1851–1936), aka: William Hope Harvey," Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture, 2012.

- 1 2 "William Hope ('Coin') Harvey," National Cyclopaedia of National Biography: Volume 18. n.c.: James T. White and Co., 1922; pp. 16-17.

- 1 2 "United States Politics: The Patriots of America," Cyclopedic Review of Current History, vol. 5 (4th Quarter 1895), pp. 865-866.

- ↑ "The Signs of the Times," Money, vol. 1, no. 7 (Nov. 1897), pg. 2.

- 1 2 George H. Strobell, "A Voluntary Referendum," Direct Legislation Record [Newark, NJ] vol. 5, no. 1 (March 1898), pg. 6.

Works

- Coin's Financial School. [1893] Chicago: Coin Publishing Co., 1894.

- A Tale of Two Nations. Chicago: Coin Publishing Co., 1894.

- The Elementary Principles of Money and Statistics on Gold and Silver. Chicago: Coin Publishing Co., 1894.

- Coin's Financial School Up to Date. Chicago: Coin Publishing Co., 1895.

- "Coin's Financial School and Its Censors," North American Review, vol. 161 (July 1, 1895), pp. 71–79.

- The Money of the People. Chicago: Charles H. Seegal Co., 1895.

- The Great Debate on the Financial Question between Hon. Roswell G. Horr, of New York, and William H. Harvey, of Illinois: The Six chapters of "Coin's Financial School" the Subject of the Debate. Chicago: Debate Publishing Co., n.d. [1895].

- The Crime of 1873 and the Harvey-Laughlin Joint Debate. Chicago: Coin Publishing Co., 1895.

- The Patriots of America. Chicago: Coin Publishing Co., 1895.

- A Common Sense Speech: Delivered at Nashville, Tennessee, December 9, 1895. Chicago: Debate Publishing Co., Dec. 1895.

- Coin on Money, Trusts, and Imperialism. Chicago: Coin Publishing Co., 1899.

- Character Building; A Book for Use in Schools. Monte Ne, AR: Herald Publishing Co., 1904.

- The Remedy. Chicago: Mundus Publishing Co., 1915.

- Report of a Conference on Character Building at Monte Né, Arkansas, in the Ozark Mountains, July 24–29, 1916. Monte Né, AR: National Committee Promoting Character Building, n.d. [1916].

- Common Sense, or, The Clot On The Brain Of The Body Politic. Monte Ne, AR: William H. (Coin) Harvey, 1920.

- Paul's School of Statesmanship. Chicago: Mundus Publishing Co., 1924.

- The Remedy That Will Bring Prosperity Quickly to Pomona, California. Monte Ne, AR: Mundus Publishing Co., n.d.

- The Pyramid Booklet: With Ten Illustrations. Monte Ne, AR: Pyramid Association, 1928.

- The Book. Rogers, AR: Mundus Publishing Co., 1930.

Further reading

- Nathan Crowder, Sunken Dreams: William 'Coin' Harvey and Monte Ne, Arkansas. MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2009.

- Richard Hofstadter, "Free Silver and the Mind of 'Coin' Harvey." The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays, 1965, pp. 238–315.

- Nan Lawler, The Ozark Trails Association. MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, 1999.

- Jeanette P. Nichols, "Bryan’s Benefactor: Coin Harvey and his World." Ohio Historical Quarterly, vol. 67 (October 1958), pp. 299–325.

- Harry A. Stokes, William Hope Harvey: Promoter and Agitator. MA thesis, Northern Illinois University, 1965.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: William Hope Harvey |

- Restoring the Historic Coin Harvey House of Huntington, West Virginia at coinharvey.com

- AmericanHeritage.com / William Hope Harvey at www.americanheritage.com Entry at AmericanHeritage.com