Clonmany

| Clonmany Cluain Maine | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

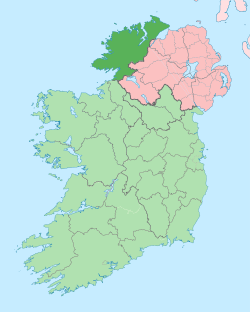

Clonmany Location in Ireland | |

| Coordinates: 55°15′45″N 7°24′45″W / 55.2625°N 7.4125°WCoordinates: 55°15′45″N 7°24′45″W / 55.2625°N 7.4125°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Ulster |

| County | County Donegal |

| Government | |

| • Dáil Éireann | Donegal North-East |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 95.01 km2 (36.68 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 470 |

| • Density | 4.9/km2 (13/sq mi) |

| Time zone | WET (UTC+0) |

| • Summer (DST) | IST (WEST) (UTC-1) |

| Area code(s) | 074, +353 74 |

| Irish Grid Reference | C374463 |

Clonmany (Irish: Cluain Maine) is a village in north-west Inishowen, in County Donegal, Ireland. The area has many local beauty spots, and the Ballyliffin area is famous for its golf course. The Urris area to the west of Clonmany village was the last outpost of the Irish language in Inishowen. In the 19th century, the area was a frequent location of poitín distillation.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Name

The name of the town in Irish - Cluain Maine has been translated as both "The Meadow of St. Maine" and "The Meadow of the Monks", with the former being the more widely recognised translation. The village is known locally as "The Cross", as the village was initially built around a crossroads.

History

The village claims to be the youngest in Inishowen. It did not feature in the census of 1841 or 1851. In the 1861 census, 112 inhabitants are recorded as living in Clonmany in 21 houses. A further 3 houses are recorded as uninhabited. [2]

The Clonmany area is steeped in history, and dolmens, forts and standing stones dot the landscape. The parish was home to a monastery, closely associated with the Morrison family, who provided the role of erenagh. The monastery was home to the Míosach a copper and silver shrine, now located in the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin. Details of local history and traditions were recorded in "The Last of the Name", recorded by schoolteacher Patrick Kavanagh (NOT the poet) from stories by Clonmany local, Charles McGlinchey.

The Poitin Republic of Urris

In the early 19th century, Urris - a townland three miles west of Clonmany - became a center of the illegal poitín distillation industry. Due to its remote and barren geography, the Urris Hills were an ideal place for poitín-making because the area was surrounded by mountains and only accessible through Mamore Gap. (London)Derry provided a major market for the trade. To protect their lucrative business, the locals barricaded the road at Crossconnell to keep out revenue police, thus creating the "Poitin Republic of Urris". This period of relative independence lasted three years. But in 1815, the authorities re-established control of the Urris Hills and brought this short period of self-rule and freedom to an end.[3][4]

The 1840 earthquake

In 1840, the village experienced an earthquake, a comparatively rare event in Ireland. The shock was also felt in the nearby town of Carndonagh. The Belfast Newsletter from Tuesday, January 28, 1840 reported that "In some places those who had retired to rest felt themselves shaken in their beds, and others were thrown from their chairs, and greatly alarmed." [5]

Irish War of Independence

In early 1920 an IRA company was established in Clonmany. It formed part of the 2nd Battalion of the Donegal IRA which was based on Carndonagh. The battalion also included companies from Culdaff, Malin, Malin Head and Carndonagh.[6]

In April 1921, Joseph Doherty, a farmer from Lenan, was found guilty during a court-martial for possessing firearms “not under effective military control”. During a police search at the home of Doherty’s mother, a single-barreled breech-loading shotgun was found concealed in a corn stack in the yard. Doherty made a statement to the Police indicating that he that knew nothing about the gun, which “must have been planted in the corn stack by someone who wished to get him into trouble.” During the trial, Doherty refused to recognize the court. The presiding judge remarked that that accused’s refusal to recognize the count had only one interpretation, that he belonged to an illegal society. [7]

The most notorious incident to occur in Clonmany during the conflict happened on May 10, 1921, when two Royal Irish Constabulary constables - Alexander Clarke and Charles Murdock - were kidnapped and murdered by the IRA. Both men were stationed at the RIC Barracks in Clonmany. They went on patrol in the evening but were captured near Straid. Both men were shot and their bodies were dumped in the sea near Binion. The body of Clarke was washed up on the shore on seashore near Binion the next day. Constable Murdock reportedly survived the initial attack despite being thrown into the sea. He swam to the shore and sought refuge among residents of Binion. However, he was betrayed to the IRA who murdered him. His body has never been found. Local tradition suggests that he was buried in a bog near Binion hill. [8]

A few weeks later, on July 10, 1921 Crown Forces raided a number of houses in Clonmany looking for Sinn Fein activists. Three unnamed young men from the village were arrested, but were released shortly afterwards and allowed to return home. [9]

Climate

The location of Clonmany on the Inishowen peninsula, and bordering Lough Swilly with views of the Atlantic provides the Clonmany area with a moderate climate; with temperate,mild summers, and winters that rarely go below freezing. The average temperatures for the area are usually warmer than the national average in winter, and cooler than the national average in summer.

Education

Clonmany has four primary schools, Clonmany N.S. (with a new state of the art school), Scoil Naomh Treasa (also known as Tiernasligo N.S. locally), Scoil Phádraig at Rashenny, and Scoil na gCluainte, or Cloontagh National School. Most students from these schools go on to attend secondary level education at Carndonagh Community School in Carndonagh, with most of the remainder attending Scoil Mhuire or Crana College in Buncrana.

Transport

Clonmany railway station opened on 1 July 1901, but finally closed on 2 December 1935.[10] The station was a stop on the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway Company (The L&LSR, the Swilly) that operated in parts of County Londonderry and County Donegal.

Culture & Tourism

Clonmany is host to the annual McGlinchey summer school, which attracts many visitors to its exhibitions and lectures on local history. Another attraction is the Clonmany festival, held annually during the week of the Irish August public holiday. The Clonmany Agricultural Show and Sheepdog Trials takes place on the Tuesday of festival week, with visitors from all over Inishowen and the Northwest of Ireland.

Sports

The Clonmany Tug of War team has enjoyed remarkable success over many years. The team was formed in 1946, and has achieved six world gold medals and twenty All Ireland titles.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ Census 2002 - Volume 1: Population Classified By Area, Central Statistics Office, Dublin, 2003

- ↑ "Parish Census 1841,1851 and 1861". Clonmany. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ https://dailyscribbling.com/the-odd-side-of-donegal/the-poitin-republic-of-urris/

- ↑ Atkinson, David; Roud, Steve (2016). Street Ballads in Nineteenth-Century Britain, Ireland, and North America: The Interface Between Print and Oral Traditions. London: Routledge. p. 140. ISBN 9781317049210.

- ↑ Belfast Newsletter 1738-1938, Tuesday, January 28, 1840; Page: 4

- ↑ ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1516.

- ↑ "GUN IN CORN STACK. TRIAL OF DONEGAL. FARMER. DECLINES TO RECOGNISE COURT.". Ballymena Weekly Telegraph. 16 April 1921.

- ↑ "MURDERED AND THROWN INTO SEA. FATE OF DONEGAL CONSTABLES.". Northern Whig. 11 May 1921.

- ↑ "Military Raids in Clonmany". Derry Journal. 13 July 1921.

- ↑ "Clonmany station" (PDF). Railscot - Irish Railways. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

- ↑ "Clonmany Tug of War Team: A History - 50 Years on". Clonmany. Retrieved 3 July 2017.