The Cloisters

view from the northeast, with bell tower (2013) | |

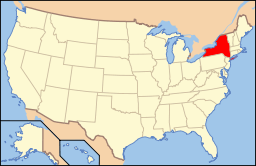

Location within New York City | |

| Established | May 10, 1938 |

|---|---|

| Location |

99 Margaret Corbin Drive, Fort Tryon Park Manhattan, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°51′53″N 73°55′55″W / 40.8648°N 73.9319°WCoordinates: 40°51′53″N 73°55′55″W / 40.8648°N 73.9319°W |

| Type | Medieval art |

| Collection size | 1,854 |

| Public transit access |

Subway: Bus: M4 |

| Website |

metmuseum |

The Cloisters is a museum in Upper Manhattan, New York City specializing in European medieval architecture, sculpture and decorative arts, and is part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Its early collection was built up by the American sculptor, art dealer and collector George Grey Barnard, and acquired by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. in 1925. Rockefeller extended the collection and in 1931 purchased the site at Washington Heights and contracted the design for the Cloisters building.

Its architectural and artistic works are largely from the Romanesque and Gothic periods. Its four cloisters; the Cuxa, Bonnefont, Trie and Saint-Guilhem cloisters, were sourced from French monasteries and abbeys. Between 1934 and 1939 they were excavated and reconstructed in a four-acre site in Washington Heights, in a large project overseen by the architect Charles Collens. The reconstructed cloisters are surrounded by early medieval gardens and a series of indoor chapels and rooms grouped by period and source location, and include the Romanesque, Fuentidueña, Unicorn, Spanish and Gothic rooms.[1]

The design, layout and ambiance of the building is intended to evoke a sense of the Medieval European monastic life through its architecture.[2] The museum contains approximately five thousand medieval works of art from the Mediterranean and Europe, mostly from the 12th to 15th centuries, that is from the Byzantine to the early renaissance periods, but also works dating from the bronze and early iron ages.

Formation and history

The basis for the museum comes from the medieval art collection of George Grey Barnard, an American sculptor and collector, who almost single-handedly established a medieval-art museum near his home in Fort Washington. Barnard was a risk taker, but constantly lived on the edge of poverty, and for period subsisted mainly on a diet of rice. His main income came from sourcing Medieval architectural artifact; supplemented by trading more established works of art, as he built up a large personal collection. During one of his frequent financial crises, Barnard sold his stock to the philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, Jr.,[3] works and structures that became the foundation and core of the Cloisters museum.[4]

The design for the 66.5-acre (26.9 ha) site at Fort Tryon Park was commissioned by Rockefeller in 1917, when he purchased the Billings Estate and other properties in the Fort Washington area and hired Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., son of one of the designers of Central Park, and the Olmsted Brothers firm to create a park, which he donated to New York City in 1935. Rockefeller and Barnard were polar opposites in temperament, and did not get on; Rockefeller was reserved, Barnard exuberant. Rockefeller was severely impacted by the stock market crash, . Eventually he acquired Barnard's collection for around $700,000, and financed the building of the site at Fort Tryon Park.

The Cloisters building and adjacent 4 acres (1.6 ha) gardens were designed by Charles Collens. It incorporates elements from abbeys in Catalan, Occitan and French origins. Parts from Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa, Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, Bonnefont-en-Comminges, Trie-sur-Baïse, and Froville were disassembled stone-by-stone and shipped to New York City, where they were reconstructed and integrated into a cohesive whole. In 1988, the Treasury Gallery within the Cloisters, containing objects used for liturgical celebrations, personal devotions, and secular uses, was renovated.[5] Other galleries were refurbished in 1998 and 1999.[6]

Construction took place over a five-year period beginning in 1934.[7][8] He bought several hundred acres of the New Jersey Palisades, which he donated to the State of New Jersey, to help preserve the view from the museum. This land is now part of the Palisades Interstate Park.[9]

The Cloisters is a well-known New York City landmark and has been used as a filming location. In 1948, the filmmaker Maya Deren used its ramparts as a backdrop for her experimental film Meditation on Violence.[10] In the same year, German director William Dieterle used the Cloisters as the location for a convent school in his film Portrait of Jennie. The 1968 film Coogan's Bluff used the site's pathways and lanes for a scenic motorcycle chase.[10]

Exterior

The museum contains architecture elements and settings relocated mostly from four French medieval abbeys: the Cuxa, Bonnefort, Trie and Saint-Guilhem cloisters. Between 1934 and 1939 they were transported, reconstructed and integrated with new buildings, in a project overseen by the architect Charles Collens. The exterior building is influenced by and contains elements from the 13th century church at Saint-Geraud at Monsempron, France, from which the northeast end of the building borrows especially. It was primarily designed by Collins, who took influence from Bernard's original Cloisters Museum.

Rockefeller's main concerns were providing an architectural feature that would memorialise the north hill as a reminder of the area's history as a revolutionary site, and also provide views over the Hudson River. The exterior was built from 1935, and contains stone from a number of European sources, primarily limestone and granite.[11] It includes four Gothic windows from the refectory at Sens, and nine arcades from a priory at Firiory.[12] The bulbous Fuentidueña Chapel was especially difficult to fit into the area.[13]

Cloisters

Cuxa

The Cuxa Cloisters are located on the south side of the building and structurally and thematically are the museum's centerpiece.[14] They are from the Benedictine Abbey of Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa, on the slopes of Mount Canigou in the northeast French Pyrenees, founded in 878.[15] The monastery was abandoned in 1791. Around half of the building was relocated to New York, after it was purchased by Barnard in 1906 and 1907.[15][16] Until then it had been in disrepair; its roof had collapsed in 1835, followed by its bell tower in 1839.[17] They were then acquired by John D. Rockefeller Jr in 1925,[18] and their installation was one of the first major undertakings by the Metropolitan after it had acquired and absorbed his purchase of Barnard's collection. After intensive work over fall and winter 1925–26, the Cuxa cloister was opened to the public on April 1, 1926.[19][20]

The Cuxa cloisters are placed at the center of the museum; its quadrangle-shaped garden once formed a center around which monks slept in cells. Its original garden seemed to have been lined by walkways around adjoining arches lined with capitals enclosing the garth. The oldest plan of the original building describes lilies and roses.[21] It is impossible now to represent solely medieval species and arrangements; those in the Cuxa cloister garden are approximations by botanists specializing in medieval history.[21] The intersection of the two walkways contains an eight-sided fountain.[22]

The walls are modern, while the original capitals and columns were cut from pink Languedoc marble from the Pyrenees.[19] The capitals were carved at different points in the abbey's history, and thus contain a variety of forms and abstract geometric patterns, including scrolling leaves, pine cones, sacred figures such as Christ, the Apostles, and angels, as well as monstrous creatures such as two-headed animals, lions restrained by apes, mythic hybrids, monstrous mouths consuming naked human torsos, and a mermaid.[23][24]

The motifs are derived from popular fables,[15] or represent the brute forces of nature or evil,[25] or are based on late 11th and 12th century monastic writings, such as those by Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153).[26] The order in which the capitals were originally placed is unknown, making their interpretation especially difficult, although an overall sequential and continuous narrative was probably never intended.[27] According to art historian Thomas Dale, to the monks, the "human figures, beasts, and monsters" may have represented the "tension between the world and the cloister, the struggle to repress the natural inclinations of the body".[28]

Bonnefont

The four walkways of the Bonnefont cloisters surround a medieval herb garden. The Bonnefont cloisters are a composite from a number of monasteries from the region, in large part from a late 12th century Cistercian abbey at Bonnefont-en-Comminges, southwest of Toulouse in southern France.[29] The abbey was intact until at least 1807, when it was documented. By the 1850s, all of its architectural features had been removed, and could be found in the surrounding areas, decorating public and private buildings.[30] Today the cloisters contain twenty-one double capitals, surrounding a garden that contains many typical features of the medieval period, including a centralwellhead, raised flower beds, and fences lined with wattle fences.[31] The marbles are highly ornate and decorated; some contain two registers, some with grotesque figures.[32]

The remnants of the Bonnefont cloisters were acquired by Barnard in 1937.[33] The garden contains a medlar tree such as that found in The Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries, and is centered around a wellhead in use since the 12th century. The entrance to the tapestries room is via a limestone portal from the Chateau de la Roche-Gencay Pitio, France, of c. 1520-30. It was acquired by Bernard along with "one hundred Gothic objects", financed by Rockefeller.[34]

Trie

The Trie cloister were originally part of a convent for Carmelite nuns at Trie-sur-Baïse, in south-western France. The original abbey, except for the church, was destroyed by Huguenots in 1571.[36] Like those from Saint-Guilhem, the Trie cloisters have been given modern roofing.[37] A number of small narrow buttresses were added to the exterior by the curator Joseph Breck, who based the design on features at Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire, England.[38]

The convent originally contained 81 white marble capitals,[39] carved between 1484-1490.[40] Eighteen are now at The Cloisters, and contain numerous biblical scenes and incidents form the lives of saints. There is evidence of secularization in some of the carvings, with biblical scenes merged with characters from legend, including Saint George and the Dragon.[39] Examples include a "wild man" confronting a grotesque monster, and a droll head wearing a very unusual and fanciful hat.[39] The biblical capitals are placed in chronological order, beginning with God in the act of creation at the north west corner, Adam and Eve in the west gallery, followed by Abraham sacrificing Isaac, and Matthew and John writing their gospels. Capitals in the south gallery illustrate scenes from the life of Christ, from the Annunciation to the Entombment.[41]

The Trie cloisters surround a rectangular garden which hosts around 80 species of plants, and contains a tall limestone cascade fountain at the center;[42] it is a composite of two late 15th- to early 16th-century French structures.[40]

Saint-Guilhem

The Saint-Guilhem cloisters originate from the site of the Benedictine monastery of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert. The architectural elements date from 804 to the 1660s.[43] From 1906, around 140 pieces were transferred to New York as one of Barnard's early acquisitions, including capitals, columns and pilasters.[44]

The unusual and innovative carvings on the marble piers and column shafts are in places coiled by extravagant foliage, including vines, and recall Roman sculpture.[45] The capitals contain acanthus leaves and grotesque heads peering out,[46] including representations of the Presentation at the Temple, Daniel in the Lions' Den,[47] and the Mouth of Hell,[48] and a number of pilasters and columns.[43] The carvings seem preoccupied with the evils of hell. Those beside the mouth of hell contain representations of the devil, tormenting beasts, with, according to art historian Bonnie Young, "animal-like body parts and cloven hoofs [as they] herd naked sinners in chains to be thrown into an upturned monster's mouth".[49]

The Saint-Guilhem cloisters is located in an indoor section of the building, and is smaller than its original incarnation.[50] It covered by a skylight and plate glass panels which conserves heat in the winter months. Its plant are mostly potted or in containers, including a 15th-century glazed earthenware vase. The small garden contains a central fountain.[51]

.jpg) Capital, La marche des âmes damnées

Capital, La marche des âmes damnées.jpg) Capitals with heads

Capitals with heads.jpg) Capital, Saint-Guilhem cloisters

Capital, Saint-Guilhem cloisters

Chapels and halls

Gothic Chapel

The Gothic chapel faces northeast and consists of two stories lit by stained glass in double-lancet windows, primarily a lancet window carved on both sides, which originates from the church of La Tricherie, between Tours and Poitiers, France. The window is positioned at the south end of the Early Gothic Hall, looking into the Gothic Chapel.[52] It is entered at ground level via a large abbey door at its east wall. The hall begins with a pointed Gothic arch, leading to high bayed ceilings, ribbed vaults and buttress on the exterior.[53]

The apse contains a large limestone sculpture of Saint Margaret dated to c. 1330 and from Lérida, Spain. The glass windows are of the 14th century with a depiction of Saint Martin of Tours and complex medallion patterns; the three center windows are from the church of Sankt Leonhard, in southern Austria, from c. 1340.[53] The glass on the east wall comes from the abbey of Evron, Normandy, and dates from around 1325.[54]

The Gothic chapel contains four tombs, each a supreme example of sepulchral art.[55] Three of the tombs are from the Bellpuig de las Avellanes monastery, in northern Spain. The effigy of a young boy is from the church of Santa Maria at Casttello de Farfanya.[55] They were built for counts, their wives and children, each with a commemorative tombstone sculptural effigy.[54] The family is associated with the church of Santa Maria at Castello de Farfanya, which was redesigned in the Gothic style for Ermengol X, Count of Urgell, who was dead by 1314.[55]

The sepulchral monument is thought to contain Ermengol VI (d. 1184). The structure is supported by three stone lions, with a group of mourners carved into the effigy slab. The panels below him show Christ in Majesty, flanked by the Twelve Apostles.[56] The female effigy was sourced in Normandy, dates to the mid 13th century, and is perhaps of Margaret of Gloucester.[57] Although resting on a modern base,[58] she is dressed in the height of contemporary aristocratic fashion, including a cotte, jewel studded belt and mantle, and an elaborate ring necklace brooch.[59]

The exterior was heavily reworked by Joseph Breck and Harold B. Willis around 1932-33. Keen to achieve both architectural harmony and preserve the proportions of the original building, they heightened the chapel, enlarged the windows, and added side windows to the bay by the apse.[60]

Fuentidueña Chapel

The Fuentidueña hall is the museum's largest room.[61] It opens with oak doors flanked by sculptures of leaping animals. It is built around the Fuentidueña Apse, a semicircular Romanesque apse dated c. 1175–1200, from the San Martín church at Fuentidueña, Segovia. The room contains a hanging crucifix and frescos honoring the Virgin Mary.[62] The chapel consists of a rectangular courtyard with covered walk ways, and beds of flowering shrubs and plants.[50]

The apse was built from over 3,300 individual stone blocks, mostly sandstone and limestone,[63] which were shipped to New York in 839 individual crates.[64] It was such a major and large installation into the Cloisters that it necessitated the knocking of the former "Special Exhibition Room". It was opening to the public in 1961, seven years after the transfer, its re-instillation was a major and highly innovative undertaking. The new space seeks to emulate a single aisle nave.[65]

The capitals include representations of the Adoration of the Magi and Daniel in the lions' den. Its piers contain the figures of Saint Martin of Tours on the left, and the angel Gabriel announcing to The Virgin on the right. The Fuentidueña room includes a number of other, mostly contemporary medieval art works set within the Fuentidueña Apse. They include, in its dome, a large fresco c. 1130–50, from the Spanish Church of Sant Joan de Tredòs, in its colorisation resembling a Byzantine mosaic and is dedicated to the ideal of Mary as the mother of God.[66] Hanging within the apse is a c. 1150–1200 crucifix from the convent of St. Clara at Astudillo.

By the 19th century the Sant Joan church was long abandoned and in disrepair. In the late 1940s the apse was moved and reconstructed in The Cloisters, a process than involved the shipping of almost 300 blocks of stone from Spain to New York. The acquisition followed three decades of complex negotiation and diplomacy between the Spanish church and both countries art historical hierarchies and governments. It was eventually exchanged in a deal that involved the transfer of six frescoes from San Baudelio de Berlanga to the Prado, on an equally long term loan.[67]

Langon Chapel

The Lagon Chapel is entered from the Romanesque hall via the doorway from Moutiers-Saint-Jean, a large Gothic doorway of elaborate French architecture, with a massive oak door. It was sourced from Moutiers-Saint-Jean Abbey in Burgundy, France. Carvings on the elaborate white oolitic limestone doorway depict the Coronation of the Virgin, and contains foliated capitals, statuettes on the outer piers, two kings positioned in the embrasures, and various kneeling angels. Carvings of angels hover in the archivolts above the kings.[68][69]

The Cathédrale Notre-Dame-du-Bourg de Digne chapel dates from c. 1126.[70] The Pontault Chapter house consists of a single aisle nave, projecting transepts[71] is taken from a small parish Benedictine church of c. 1115 from Notre Dame de Pontaut,[72] then in neglect and disrepair. When acquired its upper level was a storage place for tobacco. About three quarters of its original stonework was relocated to New York.[71] Moutiers-Saint-Jean was sacked, burned and rebuilt a number of times; in 1567 the Huguenot army cut off the heads the two kings.

In 1797 the abbey was sold as rubble for rebuilding. It lay in ruin for decades, with the sculpture severely defaced, before the door's transfer to New York, where it is now situated between the Romanesque Hall and the Langon Chapel. The doorway was the main portal of the abbey, was probably built as the south transept door, facing the cloister. The sculptured forms of the donors flanking either side of the doorway, probably represent the early Frankish kings Clovis I (d. 511), who converted to Christianity c 496, and his son Chlothar I (d. 561).[73][74] The piers are lined with elaborate and highly detailed rows of statuettes, which are mostly set in niches,[75] and baldly damaged; most have been decapitated

The heads on the right hand capital were for a time assumed to represent Henry II of England.[76] Seven capitals survive from the original church, with carvings of human heads or figures, some now conformed as identifiable as historical persons, including of Eleanor of Aquitaine.[71]

Romanesque hall

The Romanesque hall is noted for its three great church doorways. The monumental arched Burgundian entrance is from Moutier-Saint-Jean de Réôme, France, and dated to c. 1150.[77] Two animals are carved into the keystones, both on their hind legs as if about to attack each other. The capitals are lined with carvings of both real and imagined animals and birds, as well as leaves and other fauna.[78] The two other, earlier doorways are from Reugny, Allier and Poitou in central France.[2] The hall contains four large early 13th-century stone sculptures representing the Adoration of the Magi, and frescoes of a lion and a wyvern, each from the Monastery of San Pedro de Arlanza, in north central Spain.[77] On the left of the room are portraits of kings and angels, also from the monastery at Moutier-Saint-Jean.[78]

The hall contains the remnants of a church at the small Augustinian church at Reugny, consisting of three pairs of columns over a door with molded archivolts.[79] Records indicate an upper "new cloisters" installed before 1206. The site was badly damage during the French Wars of Religion and again with the French Revolution. Most of it had been sold by 1850 to Piere-Yon Verniere, from whom Barnard acquired the bricks and stone in 1906.[43]

Gardens

The Cloisters is fortified, as would have been the original churches and abbeys. During times of invasion, well developed and productive gardens would have been essential for survival.[80] Today the gardens of the Cloisters contain a wide variety of mostly rare medieval species,[81] amounting to over 250 genera of plants, flowers, herbs and trees, making it one of the world's most important collection of specialized gardens. Their design was overseen by during the museums build by James Rorimer, aided by Margaret Freeman, who conducted extensive research into both the keeping of plants and their symbolism in the Middle Ages.[82]

Today the gardens are tended to by a staff of horticulturalists; the senior members are also historians of medieval gardening techniques.[83]

Collection

Objects

_MET_DP273206.jpg)

The Cloisters contains approximately five thousand individual European medieval art works of art, mostly from the 12th to 15th centuries. It holds several ivory c. 1300 Gothic Madonna ivory statuettes, mostly French, with some English examples. Other major works include the Flemish tapestries The Hunt of the Unicorn (c. 1495–1505, probably woven in Brussels or Liège),[84] the Nine Heroes tapestries, and the and the 12th-century ivory Cloisters Cross.

Panel paintings include Robert Campin's c. 1425–28 Mérode Altarpiece panel painting,[85] the Jumieges panels by an unknown French master, and a triptych altarpiece by a follower of Rogier van der Weyden.[86]

The museum has an extensive collection of ceilings, frescoes, stained glass, illuminated manuscripts, porcelain statuettes, reliquary wood and metal shrines and crosses, and Gothic boxwood miniatures. It holds liturgical vessels, and rare pieces of Gothic furniture and metalwork.[87] Many are not associated with a particular architectural setting, so their placement in the museum may vary.[88]

Some of the objects have storied providence, including those plundering from the estates of aristocrats in the years of the French revolutionary army's occupation of the Southern Netherlands.[89] The Hunt of the Unicorn was for a period used by the French army to cloak potatoes and keep them from freezing over.[90]

.jpg) Reliquary Cross, French, c. 1180

Reliquary Cross, French, c. 1180 The Cloisters Cross, English, 12th century

The Cloisters Cross, English, 12th century Reliquary Shrine, French, c 1325–50

Reliquary Shrine, French, c 1325–50.jpg) The Crucified Christ, Northern European, c. 1300

The Crucified Christ, Northern European, c. 1300.jpg) Pietà, Southern German, c. 1375–1400

Pietà, Southern German, c. 1375–1400 Tapestry from the Hunt of the Unicorn, Brussels or Liège, c 1495 - 1505

Tapestry from the Hunt of the Unicorn, Brussels or Liège, c 1495 - 1505 Prayer Bead with the Adoration of the Magi and the Crucifixion, south Netherlandish, c. 1500–1510

Prayer Bead with the Adoration of the Magi and the Crucifixion, south Netherlandish, c. 1500–1510

Stained glass

The Cloisters' collection of stained glass includes almost three hundred panels, mostly French and Germanic, mostly from the 3rd to the early 16th century.[91] They are characterized by vivid colors and often abstract designs and patterns. Many are made from hand made opalescent glass.[92] Typical of the development of such art works, the collections' pot-metal works (i.e. containing colorants) from the High Gothic period highlight the effects of light,[91] especially the interplay between darkness and illumination.[93]

The collection grew from acquisitions in the early 20th century by Raymond Picairn, who was acquiring at a time when medieval glass was not a highly sought by connoisseurs. At the time stained glass panels were not easily extractable and particularly difficult to transport.[94]

Jane Hayward, a curator at the museum from 1969, believed stained glass was "unquestioningly the preeminent form of Gothic medieval monumental painting",[95] and began its second phase of acquisition.[95] She bought c. 1500 heraldic windows from the Rhineland, now in the Campin room with the Mérode Altarpiece, acquired in 1950. Hayward's 1980 addition lead to a redesign of the room so that the installed pieces would echo the domestic setting of the altarpiece. She wrote that the Campin room is the only gallery in the Met "where domestic rather than religious art predominates, [because] a conscious effort has been made to create fifteenth-century domestic interior similar to the one shown in [Campin]'s Annunciation panel."[96]

Other acquisitions from this time include c. 1265 grisaille panels from the Château-de-Bouvreuil in Rouen, the Cathedral of Saint-Gervais-et-Saint-Protais at Sées,[96] and panels from the Acezat collection, now in the Heroes Tapestry Hall.[97]

Grisaille panel, Cathedral of Saint-Gervais-et-Saint-Protais, Sées, 1270–80

Grisaille panel, Cathedral of Saint-Gervais-et-Saint-Protais, Sées, 1270–80 From the Schlosskapelle, Ebreichsdorf, Austria

From the Schlosskapelle, Ebreichsdorf, Austria From the Church of St. Leonhard, Lavanttal, Austria

From the Church of St. Leonhard, Lavanttal, Austria

Illuminated manuscripts

The museum has collected four medieval illuminated books, each of the first rank and of major art-historical interest. Their acquisition was a significant achievement for the museum's early collectors—but consensus among the ruling hierarchy believed the Cloisters should focus on architectural elements, sculpture and decorative arts, which would enhancing the environmental quality of the institution. Manuscripts were considered more suited to the Morgan Library in lower Manhattan.[99]

The museum has four books of exceptional rarity and quality in its collection; the French "Cloisters Apocalypse" (c. 1330),[100] the Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux (c. 1325–28), the Psalter of Bonne de Luxembourg and the Limbourg brothers' Belles Heures du Duc de Berry (c. 1399–1416).

.jpg) "Cloisters Apocalypse", French, c. 1300

"Cloisters Apocalypse", French, c. 1300 "Psalter of Bonne de Luxembourg", Jean Le Noir or follower, French, 14th century

"Psalter of Bonne de Luxembourg", Jean Le Noir or follower, French, 14th century "Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry". French, c. 1399–1416

"Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry". French, c. 1399–1416

Library and archives

The Cloisters Library is one of the Metropolitan Museum's thirteen libraries. Focusing on medieval art and architecture, it contains over 15,000 volumes of books and journals, the museum's archive administration papers, curatorial papers, dealer records, and the personal papers of Barnard, as well as early glass lantern slides of museum materials, manuscript facsimiles, scholarly records, maps and recordings of musical performances at the museum.[101] The library functions primarily as a resource for museum staff, but is available, by appointment, to other researchers, academics and students.[102]

Visual material includes early sketches and blueprints made for possible designs of the museum, as well as a number of historical photographic collections. These include photographs of medieval objects from the collection of George Joseph Demotte, and a series taken during and just after World War II showing damage sustained to a number of monuments and artifacts, including tomb effigies. They are, according to curator Lauren Jackson-Beck, of "prime importance to the art historian who is concerned with the identification of both the original work and later areas of reconstruction".[103] Two major important series are kept on microfilm; the "Index photographique de l'art en France", and the German "Marburg Picture Index".[103]

References

Notes

- ↑ Young (1979), 1

- 1 2 Parker (1992), 43

- ↑ Hayward (1992), 38

- ↑ Tomkins (1970), 308

- ↑ Brenson, Michael (1988-05-18). "Review/Art; Amid Ageless Repose, a Cloisters Gallery Is Renewed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ↑ Collins, Glenn (1998-04-21). "At the Cloisters, A Crusade Against Chaos; Curators Spending Millions To Fix 12th-Century Masonry". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ↑ New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S. (text); Postal, Matthew A. (text) (2009), Postal, Matthew A., ed., Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1, p.213

- ↑ "The Cloisters Museum and Gardens". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 15 May 2016

- ↑ Husband (2013), 16-20

- 1 2 "The Cloisters in Popular Culture: "Time in This Place Does Not Obey an Order"". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Husband, 35

- ↑ Husband, 41

- ↑ Husband, 38

- ↑ Husband (2013), 33

- 1 2 3 "Cuxa Cloister". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved May 15, 2016

- ↑ Dale (2001), 405

- ↑ Young (1979), 47

- ↑ Barnet; Wu (2005), 11

- 1 2 Husband (2013), 22

- ↑ "The Opening of the Cloisters". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Volume 21, No. 5, 1926. 113-116

- 1 2 Bayard, 37–42

- ↑ Peck (1996), 31

- ↑ Dale (2001), 407

- ↑ Horste (1982), 126

- ↑ Calkins (2005), 112

- ↑ Dale (2001), 402

- ↑ Dale (2001), 406

- ↑ Dale (2001), 410

- ↑ Rorimer (1972), 20

- ↑ Young (1979), 93

- ↑ McGowan, Sarah. "The Bonnefont Cloister Herb Garden". Fordham University. Retrieved May 22, 2016

- ↑ "Bonnefont Cloister". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 15 May 2016

- ↑ Young (1979), 98

- ↑ Young 91979), 16

- ↑ Young (1979), 12

- ↑ Husband (2013), 10

- ↑ Husband (2013), 34

- ↑ Husband (2013), 38

- 1 2 3 Young (1979), 96

- 1 2 Rorimer (1972), 22

- ↑ Young (1979), 97-9

- ↑ Barnet; Yu (2005), 18

- 1 2 3 Barnet; Wu, 58

- ↑ Husband (2013), 8

- ↑ Parker (1992), 10

- ↑ Yarrow, Andrew. "A Date With Serenity At the Cloisters". New York Times, 13 June 1986. Retrieved 21 May 2016

- ↑ "Saint-Guilhem Cloister". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 15 May 2016

- ↑ Young (1979), 24-25

- ↑ Young (1979), 26

- 1 2 Young (1979), 23

- ↑ Bayard (1985), 81

- ↑ Husband (2013), 40

- 1 2 Young (1979), 76

- 1 2 Young (1979), 80

- 1 2 3 Young (1979), 82

- ↑ Rorimer (1972), 88

- ↑ Young (1979), 80–84

- ↑ "Tomb Effigy of a Lady". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved June 5, 2016

- ↑ Brown, 409

- ↑ Young (1979), 35

- ↑ Rorimer (1951), 267

- ↑ Young (1979), 14

- ↑ Barnet; Wu, 36

- ↑ "Monumental Moving Job". New York: Life Magazine, 20 Oct 1961.

- ↑ Barnet; Wu, 38

- ↑ Young (1979), 17

- ↑ Wixom (1988–89), 36

- ↑ Forsyth (1979), 38

- ↑ Forsyth (1979), 33, 38

- ↑ Young (1979), 31

- 1 2 3 Barne (2005), 47

- ↑ Young (1979), 40

- ↑ "Doorway from Moutiers-Saint-Jean". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ↑ Rorimer (1972), 28

- ↑ Forsyth (1979), 57

- ↑ "Chapel from Notre-Dame-du-Bourg at Langon . Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 14 May 2016

- 1 2 Siple (1938), 88

- 1 2 Young (1979), 6

- ↑ Barnet; Wu (2005), 78

- ↑ Baynard (1985), 1

- ↑ Baynard (1985), vii

- ↑ Baynard (1985), 1-2

- ↑ Baynard (1985), 2

- ↑ "Gallery 017 – Unicorn Tapestry Hall (The Cloisters)". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ See Lorne Campbell's The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings, National Gallery Catalogues, 72, l, 1998, ISBN 1-85709-171-X and his 1974 Burlington article JSTOR specifically dealing with the authorship of the work

- ↑ Young (1979), 140

- ↑ Rorimer (1948), 237

- ↑ Young (1979), 125

- ↑ Ridderbos et al. (2005), 177 & 194

- ↑ Tomkins (1970), 313

- 1 2 Husband (2001), 33

- ↑ Hayward (1992), 36

- ↑ Cotter, Holland. "Luminous Canterbury Pilgrims: Stained Glass at the Cloisters". New York Times, February 27, 2014. Retrieved June 2016

- ↑ Hayworth (1992), 45

- 1 2 Clarke (2004), 31

- 1 2 Clarke (2004), 32

- ↑ Hayworth (1992), 303

- ↑ Husband (2001), 35

- ↑ Deuchler (1971), 1

- ↑ Deuchler (1969), 146

- ↑ "The Cloisters Library and Archives". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 15 May 2016

- ↑ Jackson-Beck (1989), 1

- 1 2 Jackson-Beck (1989), 2

Bibliography

- Barnet, Peter; Wu, Nancy. The Cloisters: Medieval Art and Architecture. CT: Yale University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1-5883-9176-6

- Bayard, Tania. Medieval Gardens and the Gardens of the Cloisters. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985

- Calkins, Robert. Monuments of Medieval Art. Cornell University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-8014-9306-5

- Clark, John. English and French Medieval Stained Glass in the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2003. ISBN 978-1-8725-0137-6

- Dale, Thomas E. A. "Monsters, Corporeal Deformities, and Phantasms in the Cloister of St-Michel-de-Cuxa". The Art Bulletin, volume 83, no. 3, September, 2001

- Deuchler, Florens; Hoffeld, Jeffrey; Nickel, Helmut. "The Cloisters Apocalypse: An Early Fourteenth-Century Manuscript in Facsimile". New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1971

- Deuchler, Florens. "The Cloisters: A New Center for Mediaeval Studies". The Connoisseur 172, November 1969

- Ellis, Lisa; Suda, Alexandra. "Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures". Art Gallery of Ontario, 2016. ISBN 978-1-8942-4390-2

- Forstyh, William. A Gothic Doorway from Moutiers-Saint-Jean. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979

- Hayward, Jane. "Two Grisaille Glass Panels from Saint-Denis at The Cloisters". In Parker, Elizabeth. The Cloisters: Studies in Honor of the Fiftieth Anniversary. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992. ISBN 978-0-8709-9635-1

- Jackson-Beck, Lauren. Bibliotheca Scholaria: Research Materials from the Cloisters Library. NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art; Thomas J. Watson Library, 1989. OCLC 61627180

- Horste, Kathryn. "Romanesque Sculpture in American Collections". Gesta 21, no. 2, 1982

- Hoving, Thomas. King of the Confessors. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981

- Husband, Timothy. "Creating the Cloisters". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, volume 70, no. 4, Spring, 2013

- Husband, Timothy. "Medieval Art and the Cloisters". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Volume 59, No. 1, "In: Ars Vitraria: Glass in the Metropolitan Museum of Art", 2001

- Parker, Elizabeth. The Cloisters: Studies in Honor of the Fiftieth Anniversary. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992. ISBN 978-0-8709-9635-1

- Peck, Amelia (ed). Period Rooms in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996. ISBN 978-0-8709-9805-8

- Reynolds Brown, Katharine. "Six Gothic Brooches at The Cloisters". In Parker, Elizabeth. The Cloisters: Studies in Honor of the Fiftieth Anniversary. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992. ISBN 978-0-8709-9635-1

- Ridderbos, Bernhard; Van Buren, Anne; Van Veen, Henk. Early Netherlandish Paintings: Rediscovery, Reception and Research. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-89236-816-0

- Rorimer, James J. Medieval Monuments at the Cloisters. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1972. ISBN 978-0-8709-9027-4

- Rorimer, James J. The Cloisters. The Building and the Collection of Mediaeval Art in Fort Tryon Park, 11th edition, New York 1951

- Rorimer, James J. "A Treasury at the Cloisters". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Volume 6, No. 9, 1948

- Siple, Ella. "Medieval Art at the New Cloisters and Elsewhere". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Volume 73, No. 425, 1938

- Tomkins, Calvin. "The Cloisters ... The Cloisters ... The Cloisters". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Volume 28, No. 7, 1970

- Uzig, Nicholas M. "(Re)casting the Past: The Cloisters and Medievalism". The Year's Work in Medievalism, Georgia Institute of Technology, 2012

- Wixom, William. "Medieval Sculpture at The Cloisters". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, volume 46, no. 3, Winter, 1988–1989.

- Young, Bonnie. A Walk Through The Cloisters. New York: Viking Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0-8709-9203-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Cloisters. |