Classical music

Top row: Antonio Vivaldi, Johann Sebastian Bach, George Frideric Handel, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven;

second row: Gioachino Rossini, Felix Mendelssohn, Frédéric Chopin, Richard Wagner, Giuseppe Verdi;

third row: Johann Strauss II, Johannes Brahms, Georges Bizet, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Antonín Dvořák;

bottom row: Edvard Grieg, Edward Elgar, Sergei Rachmaninoff, George Gershwin, Aram Khachaturian

Classical music is art music produced or rooted in the traditions of Western music, including both liturgical (religious) and secular music. While a more accurate term is also used to refer to the period from 1750 to 1820 (the Classical period), this article is about the broad span of time from roughly the 11th century to the present day, which includes the Classical period and various other periods.[1] The central norms of this tradition became codified between 1550 and 1900, which is known as the common-practice period. The major time divisions of Western art music are as follows :

- the early music period, which includes

- the Medieval (500–1400)

- the Renaissance (1400–1600) eras.

- Baroque (1600–1750)

- the common-practice period, which includes

- the 20th century (1901–2000) which includes

- the modern (1890–1930) that overlaps from the late-19th century,

- the impressionism (1875–1925) that also overlaps from the late-19th century

- the neoclassicism (1920–1950), predominantly in the inter-war period

- the experimental (1950–present)

- the high modern (1950–1969)

- contemporary (1945 or 1975–present) or postmodern (1930–present) eras.

European art music is largely distinguished from many other non-European classical and some popular musical forms by its system of staff notation, in use since about the 16th century.[2] Western staff notation is used by composers to indicate to the performer the pitches (e.g., melodies, basslines, chords), tempo, metre and rhythms for a piece of music. This can leave less room for practices such as improvisation and ad libitum ornamentation, which are frequently heard in non-European art music and in popular-music[3][4][5] styles such as jazz and blues. Another difference is that whereas most popular styles adopt the song (strophic) form or a derivation of this form, classical music has been noted for its development of highly sophisticated forms of instrumental music such as the concerto, symphony, sonata, and mixed vocal and instrumental styles such as opera[6] which, since they are written down, can sustain larger forms and attain a high level of complexity.[7]

The term "classical music" did not appear until the early 19th century, in an attempt to distinctly canonize the period from Johann Sebastian Bach to Beethoven as a golden age.[8] The earliest reference to "classical music" recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary is from about 1836.[1][9]

Characteristics

Given the wide range of styles in European classical music, from Medieval plainchant sung by monks to Classical and Romantic symphonies for orchestra from the 1700s and 1800s to avant-garde atonal compositions for solo piano from the 1900s, it is difficult to list characteristics that can be attributed to all works of that type. However, there are characteristics that classical music contains that few or no other genres of music contain,[10] such as the use of a printed score and the performance of very complex instrumental works (e.g., the fugue). Furthermore, while the symphony did not exist throughout the entire classical music period, from the mid-1700s to the 2000s the symphony ensemble—and the works written for it—have become a defining feature of classical music.

Literature

The key characteristic of European classical music that distinguishes it from popular music and folk music is that the repertoire tends to be written down in musical notation, creating a musical part or score. This score typically determines details of rhythm, pitch, and, where two or more musicians (whether singers or instrumentalists) are involved, how the various parts are coordinated. The written quality of the music has enabled a high level of complexity within them: J.S. Bach's fugues, for instance, achieve a remarkable marriage of boldly distinctive melodic lines weaving in counterpoint yet creating a coherent harmonic logic that would be impossible in the heat of live improvisation.[7] The use of written notation also preserves a record of the works and enables Classical musicians to perform music from many centuries ago. Musical notation enables 2000s-era performers to sing a choral work from the 1300s Renaissance era or a 1700s Baroque concerto with many of the features of the music (the melodies, lyrics, forms, and rhythms) being reproduced.

That said, the score does not provide complete and exact instructions on how to perform a historical work. Even if the tempo is written with an Italian instruction (e.g., Allegro), we do not know exactly how fast the piece should be played. As well, in the Baroque era, many works that were designed for basso continuo accompaniment do not specify which instruments should play the accompaniment or exactly how the chordal instrument (harpsichord, lute, etc.) should play the chords, which are not notated in the part (only a figured bass symbol beneath the bass part is used to guide the chord-playing performer). The performer and the conductor have a range of options for musical expression and interpretation of a scored piece, including the phrasing of melodies, the time taken during fermatas (held notes) or pauses, and the use (or choice not to use) of effects such as vibrato or glissando (these effects are possible on various stringed, brass and woodwind instruments and with the human voice).

Although Classical music in the 2000s has lost most of its tradition for musical improvisation, from the Baroque era to the Romantic era, there are examples of performers who could improvise in the style of their era. In the Baroque era, organ performers would improvise preludes, keyboard performers playing harpsichord would improvise chords from the figured bass symbols beneath the bass notes of the basso continuo part and both vocal and instrumental performers would improvise musical ornaments.[11] J.S. Bach was particularly noted for his complex improvisations.[12] During the Classical era, the composer-performer Mozart was noted for his ability to improvise melodies in different styles.[13] During the Classical era, some virtuoso soloists would improvise the cadenza sections of a concerto. During the Romantic era, Beethoven would improvise at the piano.[14] For more information, see Improvisation.

Instrumentation and vocal practices

The instruments currently used in most classical music were largely invented before the mid-19th century (often much earlier) and codified in the 18th and 19th centuries. They consist of the instruments found in an orchestra or in a concert band, together with several other solo instruments (such as the piano, harpsichord, and organ). The symphony orchestra is the most widely known medium for classical music[15] and includes members of the string, woodwind, brass, and percussion families of instruments. The concert band consists of members of the woodwind, brass, and percussion families. It generally has a larger variety and number of woodwind and brass instruments than the orchestra but does not have a string section. However, many concert bands use a double bass. The vocal practices changed over the classical period, from the single line monophonic Gregorian chant done by monks in the Medieval period to the complex, polyphonic choral works of the Renaissance and subsequent periods, which used multiple independent vocal melodies at the same time.

Medieval music

Many of the instruments used to perform medieval music still exist, but in different forms. Medieval instruments included the wood flute (which in the 21st century is made of metal), the recorder and plucked string instruments like the lute. As well, early versions of the organ, fiddle (or vielle), and trombone (called the sackbut) existed. Medieval instruments in Europe had most commonly been used singly, often self accompanied with a drone note, or occasionally in parts. From at least as early as the 13th century through the 15th century there was a division of instruments into haut (loud, shrill, outdoor instruments) and bas (quieter, more intimate instruments).[16] During the earlier medieval period, the vocal music from the liturgical genre, predominantly Gregorian chant, was monophonic, using a single, unaccompanied vocal melody line.[17] Polyphonic vocal genres, which used multiple independent vocal melodies, began to develop during the high medieval era, becoming prevalent by the later 13th and early 14th century.

Renaissance music

Many instruments originated during the Renaissance; others were variations of, or improvements upon, instruments that had existed previously. Some have survived to the present day; others have disappeared, only to be recreated in order to perform music of the period on authentic instruments. As in the modern day, instruments may be classified as brass, strings, percussion, and woodwind. Brass instruments in the Renaissance were traditionally played by professionals who were members of Guilds and they included the slide trumpet, the wooden cornet, the valveless trumpet and the sackbut. Stringed instruments included the viol, the harp-like lyre, the hurdy-gurdy, the cittern and the lute. Keyboard instruments with strings included the harpsichord and the virginals. Percussion instruments include the triangle, the Jew's harp, the tambourine, the bells, the rumble-pot, and various kinds of drums. Woodwind instruments included the double reed shawm, the reed pipe, the bagpipe, the transverse flute and the recorder. Vocal music in the Renaissance is noted for the flourishing of an increasingly elaborate polyphonic style. The principal liturgical forms which endured throughout the entire Renaissance period were masses and motets, with some other developments towards the end, especially as composers of sacred music began to adopt secular forms (such as the madrigal) for their own designs. Towards the end of the period, the early dramatic precursors of opera such as monody, the madrigal comedy, and the intermedio are seen.

Baroque music

Baroque instruments included some instruments from the earlier periods (e.g., the hurdy-gurdy and recorder) and a number of new instruments (e.g, the cello, contrabass and fortepiano). Some instruments from previous eras fell into disuse, such as the shawm and the wooden cornet. The key Baroque instruments for strings included the violin, viol, viola, viola d'amore, cello, contrabass, lute, theorbo (which often played the basso continuo parts), mandolin, cittern, Baroque guitar, harp and hurdy-gurdy. Woodwinds included the Baroque flute, Baroque oboe, rackett, recorder and the bassoon. Brass instruments included the cornett, natural horn, Baroque trumpet, serpent and the trombone. Keyboard instruments included the clavichord, tangent piano, the fortepiano (an early version of the piano), the harpsichord and the pipe organ. Percussion instruments included the timpani, snare drum, tambourine and the castanets.

One major difference between Baroque music and the classical era that followed it is that the types of instruments used in ensembles were much less standardized. Whereas a classical era string quartet consists almost exclusively of two violins, a viola and a cello, a Baroque group accompanying a soloist or opera could include one of several different types of keyboard instruments (e.g., pipe organ, harpsichord, or clavichord), additional stringed chordal instruments (e.g., a lute) and an unspecified number of bass instruments performing the basso continuo bassline, including bowed strings, woodwinds and brass instruments (e.g., a cello, contrabass, viol, bassoon, serpent, etc.).

Vocal developments in the Baroque era included the development of opera types such as opera seria and opéra comique, oratorios, cantatas and chorale.

Classical music

The term "classical music" has two meanings: the broader meaning includes all Western art music from the Medieval era to the 2000s, and the specific meaning refers to the art music from the 1750s to the early 1830s—the era of Mozart and Haydn. This section is about the more specific meaning. Classical era musicians continued to use many of instruments from the Baroque era, such as the cello, contrabass, recorder, trombone, timpani, fortepiano (the precursor to the modern piano) and organ. While some Baroque instruments fell into disuse (e.g., the theorbo and rackett), many Baroque instruments were changed into the versions that are still in use today, such as the Baroque violin (which became the violin), the Baroque oboe (which became the oboe) and the Baroque trumpet, which transitioned to the regular valved trumpet. During the Classical era, the stringed instruments used in orchestra and chamber music such as string quartets were standardized as the four instruments which form the string section of the orchestra: the violin, viola, cello and double bass. Baroque-era stringed instruments such as fretted, bowed viols were phased out. Woodwinds included the basset clarinet, basset horn, clarinette d'amour, the Classical clarinet, the chalumeau, the flute, oboe and bassoon. Keyboard instruments included the clavichord and the fortepiano. While the harpsichord was still used in basso continuo accompaniment in the 1750s and 1760s, it fell out of use in the end of the century. Brass instruments included the buccin, the ophicleide (a replacement for the bass serpent, which was the precursor of the tuba) and the natural horn.

The "standard complement" of double winds and brass in the orchestra from the first half of the 19th century is generally attributed to Beethoven. The exceptions to this are his Symphony No. 4, Violin Concerto, and Piano Concerto No. 4, which each specify a single flute. The composer's instrumentation usually included paired flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns and trumpets. Beethoven carefully calculated the expansion of this particular timbral "palette" in Symphonies 3, 5, 6, and 9 for an innovative effect. The third horn in the "Eroica" Symphony arrives to provide not only some harmonic flexibility, but also the effect of "choral" brass in the Trio. Piccolo, contrabassoon, and trombones add to the triumphal finale of his Symphony No. 5. A piccolo and a pair of trombones help deliver "storm" and "sunshine" in the Sixth. The Ninth asks for a second pair of horns, for reasons similar to the "Eroica" (four horns has since become standard); Beethoven's use of piccolo, contrabassoon, trombones, and untuned percussion—plus chorus and vocal soloists—in his finale, are his earliest suggestion that the timbral boundaries of symphony should be expanded. For several decades after he died, symphonic instrumentation was faithful to Beethoven's well-established model, with few exceptions.

Romantic music

In the Romantic era, the modern piano, with a more powerful, sustained tone and a wider range took over from the more delicate-sounding fortepiano. In the orchestra, the existing Classical instruments and sections were retained (string section, woodwinds, brass and percussion), but these sections were typically expanded to make a fuller, bigger sound. For example, while a Baroque orchestra may have had two double bass players, a Romantic orchestra could have as many as ten. "As music grew more expressive, the standard orchestral palette just wasn't rich enough for many Romantic composers." [18] New woodwind instruments were added, such as the contrabassoon, bass clarinet and piccolo and new percussion instruments were added, including xylophones, snare drums, celestes (a bell-like keyboard instrument), bells, and triangles,[18] large orchestral harps, and even wind machines for sound effects. Saxophones appear in some scores from the late 19th century onwards. While appearing only as featured solo instruments in some works, for example Maurice Ravel's orchestration of Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition and Sergei Rachmaninoff's Symphonic Dances, the saxophone is included in other works, such as Ravel's Boléro, Sergei Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet Suites 1 and 2 and many other works as a member of the orchestral ensemble. The euphonium is featured in a few late Romantic and 20th-century works, usually playing parts marked "tenor tuba", including Gustav Holst's The Planets, and Richard Strauss's Ein Heldenleben.

The Wagner tuba, a modified member of the horn family, appears in Richard Wagner's cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen and several other works by Strauss, Béla Bartók, and others; it has a prominent role in Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 7 in E Major.[19] Cornets appear in Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's ballet Swan Lake, Claude Debussy's La Mer, and several orchestral works by Hector Berlioz. Unless these instruments are played by members doubling on another instrument (for example, a trombone player changing to euphonium for a certain passage), orchestras will use freelance musicians to augment their regular rosters.

Modernist music

Modernism in music is a philosophical and aesthetic stance underlying the period of change and development in musical language that occurred from 1890 to 1930, a period of diverse reactions in challenging and reinterpreting older categories of music, innovations that lead to new ways of organizing and approaching harmonic, melodic, sonic, and rhythmic aspects of music, and changes in aesthetic worldviews in close relation to the larger identifiable period of modernism in the arts of the time. The operative word most associated with it is "innovation" (Metzer 2009, 3). Its leading feature is a "linguistic plurality", which is to say that no single music genre ever assumed a dominant position (Morgan 1984, 443).

High modern music

High modern music was developed from 1930 to 1932. Electric instruments such as the amplified electric guitar, the electric bass and the ondes Martenot first appear at about this time.

Contemporary classical music

Contemporary classical music is the period that came into prominence in the mid-1970s. It includes different variations of modernist, postmodern, neoromantic, and pluralist music.[20] However, the term may also be employed in a broader sense to refer to all post-1945 musical forms.[21]

Postmodern music

Postmodern music is a period of music that appeared at about the same time as other types of contemporary classical music; i.e around 1930. It shares characteristics with postmodernist art—that is, art that comes after and reacts against modernism.

Post-postmodern instrumentation

Many instruments that in the 2010s are associated with popular music filled important roles in early music, such as bagpipes, theorbos, vihuelas, hurdy-gurdies (hand-cranked string instruments), accordions, alphorns, hydraulises, calliopes, sistrums, and some woodwind instruments such as tin whistles, panpipes, shawms and crumhorns. On the other hand, instruments such as the acoustic guitar, once associated mainly with popular music, gained prominence in classical music in the 19th and 20th centuries in the form of the classical guitar. While equal temperament gradually accepted as the dominant musical temperament during the 19th century, different historical temperaments are often used for music from earlier periods. For instance, music of the English Renaissance is often performed in meantone temperament. As well, while professional orchestras and pop bands all around the world tune to an A fixed at 440 Hz at various times between 1834 and 1955, during the 17th and 18th century, there was a great variety in the tuning pitch, as attested to in historical pipe organs that still exist.

Performance

Performers who have studied classical music extensively are said to be "classically trained". This training may come from private lessons from instrument or voice teachers or from completion of a formal program offered by a Conservatory, college or university, such as a Bachelor of Music or Master of Music degree (which includes individual lessons from professors). In classical music, "...extensive formal music education and training, often to postgraduate [Master's degree] level" is required.[22]

Performance of classical music repertoire requires a proficiency in sight-reading and ensemble playing, harmonic principles, strong ear training (to correct and adjust pitches by ear), knowledge of performance practice (e.g., Baroque ornamentation), and a familiarity with the style/musical idiom expected for a given composer or musical work (e.g., a Brahms symphony or a Mozart concerto).

Some "popular" genre musicians have had significant classical training, such as Billy Joel, Elton John, the Van Halen brothers, Randy Rhoads and Ritchie Blackmore. Moreover, formal training is not unique to the classical genre. Many rock and pop musicians have completed degrees in commercial music programs such as those offered by the Berklee College of Music and many jazz musicians have completed degrees in music from universities with jazz programs, such as the Manhattan School of Music and McGill University.

Gender of performers

Historically, major professional orchestras have been mostly or entirely composed of male musicians. Some of the earliest cases of women being hired in professional orchestras was in the position of harpist. The Vienna Philharmonic, for example, did not accept women to permanent membership until 1997, far later than the other orchestras ranked among the world's top five by Gramophone in 2008.[23] The last major orchestra to appoint a woman to a permanent position was the Berlin Philharmonic.[24] As late as February 1996, the Vienna Philharmonic's principal flute, Dieter Flury, told Westdeutscher Rundfunk that accepting women would be "gambling with the emotional unity (emotionelle Geschlossenheit) that this organism currently has".[25] In April 1996, the orchestra's press secretary wrote that "compensating for the expected leaves of absence" of maternity leave would be a problem.[26]

In 1997, the Vienna Philharmonic was "facing protests during a [US] tour" by the National Organization for Women and the International Alliance for Women in Music. Finally, "after being held up to increasing ridicule even in socially conservative Austria, members of the orchestra gathered [on 28 February 1997] in an extraordinary meeting on the eve of their departure and agreed to admit a woman, Anna Lelkes, as harpist."[27] As of 2013, the orchestra has six female members; one of them, violinist Albena Danailova became one of the orchestra's concertmasters in 2008, the first woman to hold that position.[28] In 2012, women still made up just 6% of the orchestra's membership. VPO president Clemens Hellsberg said the VPO now uses completely screened blind auditions.[29]

In 2013, an article in Mother Jones stated that while "[m]any prestigious orchestras have significant female membership—women outnumber men in the New York Philharmonic's violin section—and several renowned ensembles, including the National Symphony Orchestra, the Detroit Symphony, and the Minnesota Symphony, are led by women violinists", the double bass, brass, and percussion sections of major orchestras "...are still predominantly male."[30] A 2014 BBC article stated that the "...introduction of 'blind' auditions, where a prospective instrumentalist performs behind a screen so that the judging panel can exercise no gender or racial prejudice, has seen the gender balance of traditionally male-dominated symphony orchestras gradually shift."[31]

Complexity

Works of classical repertoire often exhibit complexity in their use of orchestration, counterpoint, harmony, musical development, rhythm, phrasing, texture, and form. Whereas most popular styles are usually written in song forms, classical music is noted for its development of highly sophisticated instrumental musical forms,[6] like the concerto, symphony and sonata. Classical music is also noted for its use of sophisticated vocal/instrumental forms, such as opera. In opera, vocal soloists and choirs perform staged dramatic works with an orchestra providing accompaniment. Longer instrumental works are often divided into self-contained pieces, called movements, often with contrasting characters or moods. For instance, symphonies written during the Classical period are usually divided into four movements: (1) an opening Allegro in sonata form, (2) a slow movement, (3) a minuet or scherzo (in a triple metre, such as 3/4), and (4) a final Allegro. These movements can then be further broken down into a hierarchy of smaller units: first sections, then periods, and finally phrases.

History

| Periods and eras of Western classical music | |

|---|---|

| Early | |

| Medieval | c. 500–1400 |

| Renaissance | c. 1400–1600 |

| Common practice | |

| Baroque | c. 1600–1750 |

| Classical | c. 1730–1820 |

| Romantic | c. 1780–1910 |

| Impressionist | c. 1875–1925 |

| Modern and contemporary | |

| c. 1890–1975 | |

| 20th century | (1900–2000) |

| c. 1975–present | |

| 21st century | (2000–present) |

The major time divisions of classical music up to 1900 are the early music period, which includes Medieval (500–1400) and Renaissance (1400–1600) eras, and the Common practice period, which includes the Baroque (1600–1750), Classical (1730–1820) and Romantic (1780–1910) eras. Since 1900, classical periods have been reckoned more by calendar century than by particular stylistic movements that have become fragmented and difficult to define. The 20th century calendar period (1901–2000) includes most of the early modern musical era (1890–1930), the entire high modern (mid 20th-century), and the first 25 years of the contemporary (1945 or 1975–current) or postmodern musical era (1930–current). The 21st century has so far been characterized by a continuation of the contemporary/postmodern musical era.

The dates are generalizations, since the periods and eras overlap and the categories are somewhat arbitrary, to the point that some authorities reverse terminologies and refer to a common practice "era" comprising baroque, classical, and romantic "periods".[32] For example, the use of counterpoint and fugue, which is considered characteristic of the Baroque era (or period), was continued by Haydn, who is classified as typical of the Classical era. Beethoven, who is often described as a founder of the Romantic era, and Brahms, who is classified as Romantic, also used counterpoint and fugue, but other characteristics of their music define their era.

The prefix neo- is used to describe a 19th-, 20th-, or 21st-century composition written in the style of an earlier era, such as Classical or Romantic. Stravinsky's Pulcinella, for example, is a neoclassical composition because it is stylistically similar to works of the Baroque era.

Roots

Burgh (2006), suggests that the roots of Western classical music ultimately lie in ancient Egyptian art music via cheironomy and the ancient Egyptian orchestra, which dates to 2695 BC.[33] The development of individual tones and scales was made by ancient Greeks such as Aristoxenus and Pythagoras.[34] Pythagoras created a tuning system and helped to codify musical notation. Ancient Greek instruments such as the aulos (a reed instrument) and the lyre (a stringed instrument similar to a small harp) eventually led to the modern-day instruments of a classical orchestra.[35] The antecedent to the early period was the era of ancient music before the fall of the Roman Empire (476 AD). Very little music survives from this time, most of it from ancient Greece.

Early period

The Medieval period includes music from after the fall of Rome to about 1400. Monophonic chant, also called plainsong or Gregorian chant, was the dominant form until about 1100.[36] Polyphonic (multi-voiced) music developed from monophonic chant throughout the late Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, including the more complex voicings of motets. The Renaissance era was from 1400 to 1600. It was characterized by greater use of instrumentation, multiple interweaving melodic lines, and the use of the first bass instruments. Social dancing became more widespread, so musical forms appropriate to accompanying dance began to standardize. It is in this time that the notation of music on a staff and other elements of musical notation began to take shape.[37] This invention made possible the separation of the composition of a piece of music from its transmission; without written music, transmission was oral, and subject to change every time it was transmitted. With a musical score, a work of music could be performed without the composer's presence.[36] The invention of the movable-type printing press in the 15th century had far-reaching consequences on the preservation and transmission of music.[38]

Typical stringed instruments of the early period include the harp, lute, vielle, and psaltery, while wind instruments included the flute family (including recorder), shawm (an early member of the oboe family), trumpet, and the bagpipes. Simple pipe organs existed, but were largely confined to churches, although there were portable varieties.[39] Later in the period, early versions of keyboard instruments like the clavichord and harpsichord began to appear. Stringed instruments such as the viol had emerged by the 16th century, as had a wider variety of brass and reed instruments. Printing enabled the standardization of descriptions and specifications of instruments, as well as instruction in their use.[40]

Common practice period

The common practice period is when many of the ideas that make up western classical music took shape, standardized, or were codified. It began with the Baroque era, running from roughly 1600 to the middle of the 18th century. The Classical era followed, ending roughly around 1820. The Romantic era ran through the 19th century, ending about 1910.

Baroque music

Baroque music is characterized by the use of complex tonal counterpoint and the use of a basso continuo, a continuous bass line. Music became more complex in comparison with the songs of earlier periods.[15] The beginnings of the sonata form took shape in the canzona, as did a more formalized notion of theme and variations. The tonalities of major and minor as means for managing dissonance and chromaticism in music took full shape.[41]

During the Baroque era, keyboard music played on the harpsichord and pipe organ became increasingly popular, and the violin family of stringed instruments took the form generally seen today. Opera as a staged musical drama began to differentiate itself from earlier musical and dramatic forms, and vocal forms like the cantata and oratorio became more common.[42] Vocalists began adding embellishments to melodies.[15] Instrumental ensembles began to distinguish and standardize by size, giving rise to the early orchestra for larger ensembles, with chamber music being written for smaller groups of instruments where parts are played by individual (instead of massed) instruments. The concerto as a vehicle for solo performance accompanied by an orchestra became widespread, although the relationship between soloist and orchestra was relatively simple.

The theories surrounding equal temperament began to be put in wider practice, especially as it enabled a wider range of chromatic possibilities in hard-to-tune keyboard instruments. Although Bach did not use equal temperament, as a modern piano is generally tuned, changes in the temperaments from the meantone system, common at the time, to various temperaments that made modulation between all keys musically acceptable, made possible Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier.[43]

Classical era (or period) music

The Classical era, from about 1750 to 1820, established many of the norms of composition, presentation, and style, and was also when the piano became the predominant keyboard instrument. The basic forces required for an orchestra became somewhat standardized (although they would grow as the potential of a wider array of instruments was developed in the following centuries). Chamber music grew to include ensembles with as many as 8 to 10 performers for serenades. Opera continued to develop, with regional styles in Italy, France, and German-speaking lands. The opera buffa, a form of comic opera, rose in popularity. The symphony came into its own as a musical form, and the concerto was developed as a vehicle for displays of virtuoso playing skill. Orchestras no longer required a harpsichord (which had been part of the traditional continuo in the Baroque style), and were often led by the lead violinist (now called the concertmaster).[44]

Wind instruments became more refined in the Classical era. While double reeded instruments like the oboe and bassoon became somewhat standardized in the Baroque, the clarinet family of single reeds was not widely used until Mozart expanded its role in orchestral, chamber, and concerto settings.

Romantic era music

The music of the Romantic era, from roughly the first decade of the 19th century to the early 20th century, was characterized by increased attention to an extended melodic line, as well as expressive and emotional elements, paralleling romanticism in other art forms. Musical forms began to break from the Classical era forms (even as those were being codified), with free-form pieces like nocturnes, fantasias, and preludes being written where accepted ideas about the exposition and development of themes were ignored or minimized.[45] The music became more chromatic, dissonant, and tonally colorful, with tensions (with respect to accepted norms of the older forms) about key signatures increasing.[46] The art song (or Lied) came to maturity in this era, as did the epic scales of grand opera, ultimately transcended by Richard Wagner's Ring cycle.[47]

In the 19th century, musical institutions emerged from the control of wealthy patrons, as composers and musicians could construct lives independent of the nobility. Increasing interest in music by the growing middle classes throughout western Europe spurred the creation of organizations for the teaching, performance, and preservation of music. The piano, which achieved its modern construction in this era (in part due to industrial advances in metallurgy) became widely popular with the middle class, whose demands for the instrument spurred a large number of piano builders. Many symphony orchestras date their founding to this era.[46] Some musicians and composers were the stars of the day; some, like Franz Liszt and Niccolò Paganini, fulfilled both roles.[48]

The family of instruments used, especially in orchestras, grew. A wider array of percussion instruments began to appear. Brass instruments took on larger roles, as the introduction of rotary valves made it possible for them to play a wider range of notes. The size of the orchestra (typically around 40 in the Classical era) grew to be over 100.[46] Gustav Mahler's 1906 Symphony No. 8, for example, has been performed with over 150 instrumentalists and choirs of over 400.

European cultural ideas and institutions began to follow colonial expansion into other parts of the world. There was also a rise, especially toward the end of the era, of nationalism in music (echoing, in some cases, political sentiments of the time), as composers such as Edvard Grieg, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and Antonín Dvořák echoed traditional music of their homelands in their compositions.[49]

20th and 21st centuries

Modern, high modern, post-modern, post-postmodern, or contemporary music

Encompassing a wide variety of post-Romantic styles composed through the year 2000, 20th-century classical music includes late romantic, impressionist, neoclassical, neoromantic, neomedieval, and postmodern styles of composition. Modernism (1890–1930) marked an era when many composers rejected certain values of the common practice period, such as traditional tonality, melody, instrumentation, and structure. The high-modern era saw the emergence of neo-classical and serial music. A few authorities have claimed high-modernism as the beginning of postmodern music from about 1930.[50][51] Others have more or less equated postmodern music with the "contemporary music" composed from the late 20th century through to the early 21st century.[52][53]

Women in classical music

Almost all of the composers who are described in music textbooks on classical music and whose works are widely performed as part of the standard concert repertoire are male composers, even though there has been a large number of women composers throughout the classical music period. Musicologist Marcia Citron has asked "[w]hy is music composed by women so marginal to the standard 'classical' repertoire?"[54] Citron "examines the practices and attitudes that have led to the exclusion of women composers from the received 'canon' of performed musical works." She argues that in the 1800s, women composers typically wrote art songs for performance in small recitals rather than symphonies intended for performance with an orchestra in a large hall, with the latter works being seen as the most important genre for composers; since women composers did not write many symphonies, they were deemed to be not notable as composers.[54] In the "...Concise Oxford History of Music, Clara S[c]humann is one of the only [sic] female composers mentioned."[55] Abbey Philips states that "[d]uring the 20th century the women who were composing/playing gained far less attention than their male counterparts."[55]

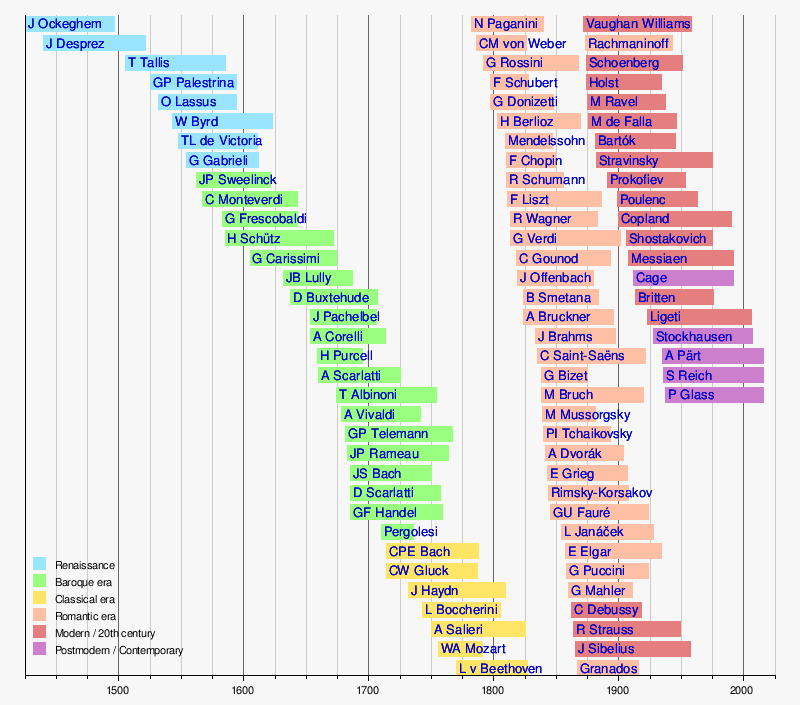

Timeline of composers

Significance of written notation

Literalist view of the significance of the score

While there are differences between particular performances of a classical work, a piece of classical music is generally held to transcend any interpretation of it. The use of musical notation is an effective method for transmitting classical music, since the written music contains the technical instructions for performing the work.

The written score, however, does not usually contain explicit instructions as to how to interpret the piece in terms of production or performance, apart from directions for dynamics, tempo and expression (to a certain extent). This is left to the discretion of the performers, who are guided by their personal experience and musical education, their knowledge of the work's idiom, their personal artistic tastes, and the accumulated body of historic performance practices.

Criticism of the literalist view

Some critics express the opinion that it is only from the mid-19th century, and especially in the 20th century, that the score began to hold such a high significance. Previously, improvisation (in preludes, cadenzas and ornaments), rhythmic flexibility (e.g., tempo rubato), improvisatory deviation from the score and oral tradition of playing was integral to the style. Yet in the spring of 1907, this oral tradition and passing on of stylistic features within classical music disappeared, only to re-emerge in September 1911 as if it had never been gone. Classical musicians tend to use scores and the parts extracted from them to play music. Yet, even with notation providing the key elements of the music, there is considerable latitude in the performance of the works. Some of this latitude results from the inherent limitations of musical notation, though attempts to supplement traditional notation with signs and annotations indicating more subtle nuances tend to overwhelm and paralyse the performer.

Some quotes that highlight a criticism of overvaluing of the score:

- "... one of the most stubborn modern misconceptions concerning baroque music is that a metronomic regularity was intended" (Baroque Interpretation in Grove 5th edition by Robert Donington)

- "Too many teachers, conditioned to 20th century ideas, teach Bach and other Baroque music exactly the wrong way. This leads to what musicologist Sol Babitz calls 'sewing machine Bach'."[56]

- "... tendency to look alike, sound alike and think alike. The conservatories are at fault and they have been at fault for many years now. Any sensitive musician going around the World has noted the same thing. The conservatories, from Moscow and Leningrad to Juilliard, Curtis and Indiana, are producing a standardized product.

[...] clarity, undeviating rhythm, easy technique, 'musicianship'. I put the word musicianship in quotes, because as often as not, it is a false kind of musicianship – a musicianship that sees the tree and not the forest, that takes care of the detail but ignores the big picture; a musicianship that is tied to the printed note rather than to emotional meaning of a piece.

The fact remains that there is a dreadful uniformity today and also an appalling lack of knowledge about the culture and performance traditions of the past." ("Music Schools Turning out Robots?"[56] by Harold C. Schonberg)

Improvisation

Improvisation once played an important role in classical music. A remnant of this improvisatory tradition in classical music can be heard in the cadenza, a passage found mostly in concertos and solo works, designed to allow skilled performers to exhibit their virtuoso skills on the instrument. Traditionally this was improvised by the performer; however, it is often written for (or occasionally by) the performer beforehand. Improvisation is also an important aspect in authentic performances of operas of Baroque era and of bel canto (especially operas of Vincenzo Bellini), and is best exemplified by the da capo aria, a form by which famous singers typically perform variations of the thematic matter of the aria in the recapitulation section ('B section' / the 'da capo' part). An example is Beverly Sills' complex, albeit pre-written, variation of "Da tempeste il legno infranto" from Händel's Giulio Cesare.

Its written transmission, along with the veneration bestowed on certain classical works, has led to the expectation that performers will play a work in a way that realizes in detail the original intentions of the composer. During the 19th century the details that composers put in their scores generally increased. Yet the opposite trend—admiration of performers for new "interpretations" of the composer's work—can be seen, and it is not unknown for a composer to praise a performer for achieving a better realization of the original intent than the composer was able to imagine. Thus, classical performers often achieve high reputations for their musicianship, even if they do not compose themselves. Generally however, it is the composers who are remembered more than the performers.

The primacy of the composer's written score has also led, today, to a relatively minor role played by improvisation in classical music, in sharp contrast to the practice of musicians who lived during the medieval, renaissance, baroque and early romantic eras. Improvisation in classical music performance was common during both the Baroque and early romantic eras, yet lessened strongly during the second half of the 20th century. During the classical era, Mozart and Beethoven often improvised the cadenzas to their piano concertos (and thereby encouraged others to do so), but for violin concertos they provided written cadenzas for use by other soloists. In opera, the practice of singing strictly by the score, i.e. come scritto, was famously propagated by soprano Maria Callas, who called this practice 'straitjacketing' and implied that it allows the intention of the composer to be understood better, especially during studying the music for the first time.[57]

Relationship to other music traditions

Popular music

Classical music has often incorporated elements or material from popular music of the composer's time. Examples include occasional music such as Brahms' use of student drinking songs in his Academic Festival Overture, genres exemplified by Kurt Weill's The Threepenny Opera, and the influence of jazz on early- and mid-20th-century composers including Maurice Ravel, exemplified by the movement entitled "Blues" in his sonata for violin and piano.[58] Certain postmodern, minimalist and postminimalist classical composers acknowledge a debt to popular music.[59]

Numerous examples show influence in the opposite direction, including popular songs based on classical music, the use to which Pachelbel's Canon has been put since the 1970s, and the musical crossover phenomenon, where classical musicians have achieved success in the popular music arena.[60] In heavy metal, a number of lead guitarists (playing electric guitar) modeled their playing styles on Baroque or Classical era instrumental music, including Ritchie Blackmore and Randy Rhoads.

Folk music

Composers of classical music have often made use of folk music (music created by musicians who are commonly not classically trained, often from a purely oral tradition). Some composers, like Dvořák and Smetana,[61] have used folk themes to impart a nationalist flavor to their work, while others like Bartók have used specific themes lifted whole from their folk-music origins.[62]

Commercialization

Certain staples of classical music are often used commercially (either in advertising or in movie soundtracks). In television commercials, several passages have become clichéd, particularly the opening of Richard Strauss' Also sprach Zarathustra (made famous in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey) and the opening section "O Fortuna" of Carl Orff's Carmina Burana, often used in the horror genre; other examples include the Dies Irae from the Verdi Requiem, Edvard Grieg's In the Hall of the Mountain King from Peer Gynt, the opening bars of Beethoven's Symphony No. 5, Wagner's Ride of the Valkyries from Die Walküre, Rimsky-Korsakov's Flight of the Bumblebee, and excerpts of Aaron Copland's Rodeo. Several works from the Golden Age of Animation matched the action to classical music. Notable examples are Walt Disney's Fantasia, Tom and Jerry's Johann Mouse, and Warner Bros.' Rabbit of Seville and What's Opera, Doc?.

Similarly, movies and television often revert to standard, clichéd excerpts of classical music to convey refinement or opulence: some of the most-often heard pieces in this category include Bach´s Cello Suite No. 1, Mozart's Eine kleine Nachtmusik, Vivaldi's Four Seasons, Mussorgsky's Night on Bald Mountain (as orchestrated by Rimsky-Korsakov), and Rossini's William Tell Overture. The same passages are often used by telephone call centres to induce a sense of calm in customers waiting in a queue. Shawn Vancour argues that the commercialization of classical music in the early 20th century may have harmed the music industry through inadequate representation.[63]

Public domain

Since the range of production of classical music is from 14th century to 21st century, most of this music (14th to early 20th century) belongs to the public domain, mainly sheet music and tablatures. Some projects like Musopen and Open Goldberg Variations were created to produce musical audio files of high quality and release them into the public domain, most of them are available at the Internet Archive website.

The Open Goldberg Variations project released a braille format into the public domain that can be used to produce paper or electronic scores, Braille e-books, for blind people.[64]

Education

During the 1990s, several research papers and popular books wrote on what came to be called the "Mozart effect": an observed temporary, small elevation of scores on certain tests as a result of listening to Mozart's works. The approach has been popularized in a book by Don Campbell, and is based on an experiment published in Nature suggesting that listening to Mozart temporarily boosted students' IQ by 8 to 9 points.[65] This popularized version of the theory was expressed succinctly by the New York Times music columnist Alex Ross: "researchers... have determined that listening to Mozart actually makes you smarter."[66] Promoters marketed CDs claimed to induce the effect. Florida passed a law requiring toddlers in state-run schools to listen to classical music every day, and in 1998 the governor of Georgia budgeted $105,000 per year to provide every child born in Georgia with a tape or CD of classical music. One of the co-authors of the original studies of the Mozart effect commented "I don't think it can hurt. I'm all for exposing children to wonderful cultural experiences. But I do think the money could be better spent on music education programs."[67]

In 1996/97, a research study was conducted on a large population of middle age students in the Cherry Creek School District in Denver, Colorado, USA. The study showed that students who actively listen to classical music before studying had higher academic scores. The research further indicated that students who listened to the music prior to an examination also had positively elevated achievement scores. Students who listened to rock-and-roll or Country music had moderately lower scores. The study further indicated that students who used classical music during the course of study had a significant leap in their academic performance; whereas, those who listened to other types of music had significantly lowered academic scores. The research was conducted over several schools within the Cherry Creek School District and was conducted through the University of Colorado. This study is reflective of several recent studies (i.e. Mike Manthei and Steve N. Kelly of the University of Nebraska at Omaha; Donald A. Hodges and Debra S. O'Connell of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro; etc.) and others who had significant results through the discourse of their work.[68]

See also

Nation-specific:

- American classical music

- Australian classical music

- Canadian classical music

- French classical music

- Indian classical music

- Italian classical music

- Russian classical music

- Classical music of the United Kingdom

Notes

- 1 2 "Classical", The Oxford Concise Dictionary of Music, ed. Michael Kennedy, (Oxford, 2007), Oxford Reference Online. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ Chew, Geffrey & Rastall, Richard. "Notation, §III, 1(vi): Plainchant: Pitch-specific notations, 13th–16th centuries". In L. Root, Deane. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- ↑ Malm, W.P.; Hughes, David W. "Japan, §III, 1: Notation systems: Introduction". In L. Root, Deane. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- ↑ Ian D. Bent; David W. Hughes; Robert C. Provine; Richard Rastall; Anne Kilmer. "Notation, §I: General". In L. Root, Deane. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- ↑ Middleton, Richard. "Popular music, §I, 4: Europe & North America: Genre, form, style". In L. Root, Deane. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- 1 2 Julian Johnson (2002) Who Needs Classical Music?: Cultural Choice and Musical Value: p. 63.

- 1 2 Knud Jeppesen: "Bach's music grows out of an ideally harmonic background, against which the voices develop with a bold independence that is often breath-taking." Quoted from Adele Katz (1946; reprinted 2007)

- ↑ Rushton, Julian, Classical Music, (London, 1994), 10

- ↑ The Oxford English Dictionary (2007). "classical, a.". The OED Online. Retrieved May 10, 2007.

- ↑ Kennedy, Michael (2006), The Oxford Dictionary of Music, p. 178

- ↑ Gabriel Solis, Bruno Nettl. Musical Improvisation: Art, Education, and Society. University of Illinois Press, 2009. p. 150

- ↑ "On Baroque Improvisation". Community.middlebury.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ↑ David Grayson. Mozart: Piano Concertos Nos. 20 and 21. Cambridge University Press, 1998. p. 95

- ↑ Tilman Skowroneck. Beethoven the Pianist. Cambridge University Press, 2010. p. 160

- 1 2 3 Kirgiss, Crystal (2004). Classical Music. Black Rabbit Books. ISBN 978-1-58340-674-8.

- ↑ (Bowles 1954, 119 et passim)

- ↑ Hoppin (1978) p.57

- 1 2 "Romantic music: a beginner's guide – Music Periods". Classic FM. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ↑ "The Wagner Tuba". The Wagner Tuba. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ↑ Botstein "Modernism" §9: The Late 20th Century (subscription access).

- ↑ "Contemporary" in Du Noyer 2003, 272.

- ↑ "Job Guide – Classical Musician". Inputyouth.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ↑ "The world's greatest orchestras". gramophone.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ↑ James R. Oestreich, "Berlin in Lights: The Woman Question", Arts Beat, The New York Times, 16 November 2007

- ↑ Westdeutscher Rundfunk Radio 5, "Musikalische Misogynie", 13 February 1996, transcribed by Regina Himmelbauer; translation by William Osborne

- ↑ "The Vienna Philharmonic's Letter of Response to the Gen-Mus List". Osborne-conant.org. 1996-02-25. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ Jane Perlez, "Vienna Philharmonic Lets Women Join in Harmony", The New York Times, February 28, 1997

- ↑ Vienna opera appoints first ever female concertmaster, France 24

- ↑ James R. Oestrich, "Even Legends Adjust To Time and Trend, Even the Vienna Philharmonic", The New York Times, 28 February 1998

- ↑ Hannah Levintova. "Here's Why You Seldom See Women Leading a Symphony". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ↑ Burton, Clemency (2014-10-21). "Culture – Why aren't there more women conductors?". BBC. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ↑ Vladimir J. Konecni (2009). "Mode and tempo in Western classical music of the common-practice era" (PDF). Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ Burgh, Theodore W. (2006). Listening to Artifacts: Music Culture in Ancient Israel/Palestine. T. & T. Clark Ltd. ISBN 0567025527.

- ↑ Grout, p. 28

- ↑ Grout (1988)

- 1 2 Grout, pp. 75–76

- ↑ Grout, p. 61

- ↑ Grout, pp. 175–176

- ↑ Grout, pp. 72–74

- ↑ Grout, pp. 222–225

- ↑ Grout, pp. 300–332

- ↑ Grout, pp. 341–355

- ↑ Grout, p. 378

- ↑ Grout, p. 463

- ↑ Swafford, p. 200

- 1 2 3 Swafford, p. 201

- ↑ Grout, pp. 595–612

- ↑ Grout, p. 543

- ↑ Grout, pp. 634,641–2

- ↑ Karolyi 1994, 135

- ↑ Meyer 1994, 331–32

- ↑ Sullivan 1995, 217

- ↑ Beard and Gloag 2005, 142

- 1 2 Citron, Marcia J. "Gender and the Musical Canon." CUP Archive, 1993.

- 1 2 Abbey Philips (2011-09-01). "The history of women and gender roles in music". Rvanews.com. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- 1 2 "Music Schools Turning out Robots?" by Harold C. Schonberg; Daytona Beach Morning Journal – October 19, 1969

- ↑ "In other words, exactly as it's written, nothing more and nothing less, which is what I call straitjacketing." quoted in Huffington, Arianna (2002). Maria Callas: The Woman behind the Legend, p.76. Cooper Square. ISBN 9781461624295.

- ↑ Kelly, Barbara L. "Ravel, Maurice, §3: 1918–37". In L. Root, Deane. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- ↑ See, for example, Siôn, Pwyll Ap. "Nyman, Michael". In L. Root, Deane. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- ↑ Notable examples are the Hooked on Classics series of recordings made by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in the early 1980s and the classical crossover violinists Vanessa Mae and Catya Maré.

- ↑ Yeomans, David (2006). Piano Music of the Czech Romantics: A Performer's Guide. Indiana University Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-253-21845-4.

- ↑ Stevens, Haley; Gillies, Malcolm (1993). The Life and Music of Béla Bartók. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 129. ISBN 0-19-816349-5.

- ↑ Vancour, Shawn (March 2009). "Popularizing the Classics: Radio's Role in the Music Appreciation Movement 1922–34.". Media, Culture and Society. 31 (2): 19. doi:10.1177/0163443708100319. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ↑ Braille edition of the Open Goldberg Variations ny robertDouglass, Open Goldberg Variations, 23 March 2014

- ↑ Prelude or requiem for the 'Mozart effect'? Nature 400 (August 26, 1999): 827.

- ↑ Ross, Alex. "Classical View; Listening To Prozac... Er, Mozart", The New York Times, August 28, 1994. Retrieved on May 16, 2008.

- ↑ Goode, Erica. "Mozart for Baby? Some Say, Maybe Not", The New York Times, August 3, 1999. Retrieved on May 16, 2008.

- ↑ "The Impact of Music Education on Academic Achievement" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 16, 2012. Retrieved February 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)

References

- Grout, Donald Jay (1973). A History of Western Music. W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-09416-2.

- Grout, Donald J.; Palisca, Claude V. (1988). A History of Western Music. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-95627-6.

- Johnson, Julian (2002), Who Needs Classical Music?: Cultural Choice and Musical Value. Oxford University Press, 140pp.

- Karolyi, Otto. 1994. Modern British Music: The Second British Musical Renaissance—From Elgar to P. Maxwell Davies. Rutherford, Madison, Teaneck: Farleigh Dickinson University Press; London and Toronto: Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8386-3532-6.

- Katz, Adele (1946; reprinted 2007), Challenge to Musical Tradition – A New Concept of Tonality. Alfred A. Knopf/reprinted by Katz Press, 444pp., ISBN 1-4067-5761-6.

- Kennedy, Michael (2006), The Oxford Dictionary of Music, 985 pages, ISBN 0-19-861459-4

- Lebrecht, Norman (1996). When the Music Stops: Managers, Maestros and the Corporate Murder of Classical Music. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-01025-6.

- Metzer, David Joel. 2009. Musical Modernism at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century. Music in the Twentieth Century 26. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51779-9.

- Meyer, Leonard B. 1994. Music, the Arts, and Ideas: Patterns and Predictions in Twentieth-Century Culture, second edition. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-52143-5.

- Morgan, Robert P. 1984. "Secret Languages: The Roots of Musical Modernism". Critical Inquiry 10, no. 3 (March): 442–61.

- Swafford, Jan (1992). The Vintage Guide to Classical Music. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-72805-8.

Further reading

- Copland, Aaron (1957) What to Listen for in Music; rev. ed. McGraw-Hill. (paperback).

- Grout, Donald Jay; Palisca, Claude V. (1996) A History of Western Music, Fifth edition. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-96904-5 (hardcover).

- Hanning, Barbara Russano; Grout, Donald Jay (1998 rev. 2009) Concise History of Western Music. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-92803-9 (hardcover).

- Johnson, Julian (2002) Who Needs Classical Music?: cultural choice and musical value. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514681-6.

- Kamien, Roger (2008) Music: an appreciation; 6th brief ed. McGraw-Hill ISBN 978-0-07-340134-8

- Lihoreau, Tim; Fry, Stephen (2004) Stephen Fry's Incomplete and Utter History of Classical Music. Boxtree. ISBN 978-0-7522-2534-0

- Scholes, Percy Alfred; Arnold, Denis (1988) The New Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-311316-3 (paperback).

- Schick, Kyle (2012). "Improvisation: Performer as Co-composer", Musical Offerings: Vol. 3: No. 1, Article 3. Available at http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol3/iss1/3.

- Sorce Keller, Marcello (2011) What Makes Music European. Looking Beyond Sound. Latham, NJ: Scarecrow Press (USA).

- Taruskin, Richard (2005, rev. Paperback version 2009) Oxford History of Western Music. Oxford University Press (USA). ISBN 978-0-19-516979-9 (Hardback), ISBN 978-0-19-538630-1 (Paperback)

- Gray, Anne; (2007) The World of Women in Classical Music, Wordworld Publications. ISBN 1-59975-320-0 (Paperback)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Classical music |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for European classical music. |

Media related to Classical music at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Classical music at Wikimedia Commons- Historical classical recordings from the British Library Sound Archive (available only to users in the member countries of the European Union)

- Chronological list of recorded classical composers

- Music World, timeline, composers, instruments