Clan MacLeod

| Clan MacLeod | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clann MhicLeòid[1] | |||

Crest: A bull's head cabossed sable, horned Or, between two flags gules, staved at the first | |||

| Motto | Hold fast | ||

| Profile | |||

| District | Inner Hebrides | ||

| Plant badge | Juniper | ||

| Chief | |||

| |||

|

Hugh Magnus MacLeod of MacLeod (there is a rival claimant to chiefship)[2] | |||

| 30th Hereditary Chief Clan MacLeod Chief of the Name and Arms of MacLeod (MacLeòid[1]) | |||

| Seat | Dunvegan Castle[3] | ||

| Historic seat | Dunvegan Castle[3] | ||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

Clan MacLeod (/ˌklæn mᵻˈklaʊd/; Scottish Gaelic: Clann MhicLeòid; [ˈkʰl̪ˠau̯n̪ˠ viçkʲˈʎɔːhtʲ]) is a Highland Scottish clan associated with the Isle of Skye. There are two main branches of the clan: the MacLeods of Harris and Dunvegan, whose chief is MacLeod of MacLeod, are known in Gaelic as Sìol Tormoid ("seed of Tormod"); the Clan MacLeod of Lewis and Raasay, whose chief is Macleod of The Lewes (Scottish Gaelic: Mac Ghille Chaluim),[1] are known in Gaelic as Sìol Torcaill ("seed of Torcall"). Both branches claim descent from Leòd, who lived in the 13th century.

History

Origins

The surname MacLeod means 'son of Leod'. The name Leod is an Anglicization of the Scottish Gaelic name Leòd, which is thought to have been derived from the Old Norse.[4] Clann means family, while mhic is the genitive of mac, the Gaelic for son, and Leòid is the genitive of Leòd. The whole phrase therefore means The family of the son of Leod.

The Clan MacLeod of Lewis claims its descent from Leod, who according to MacLeod tradition was a younger son of Olaf the Black, King of Mann (r.1229–1237). However, articles have been published in the Clan MacLeod magazine which suggest an alternative genealogy for Leod, one in which he was not son of Olaf, but a 3rd cousin (some removed) from Magnus the last King of Mann. In these alternative genealogies, using the genealogy of Christina MacLeod, great granddaughter of Leod, who married Hector Reaganach (McLean/McLaine) these articles suggest that the relationship to the Kings of Mann was through a female line, that of Helga of the beautiful hair. The dating of Christina's genealogy and the ability to line it up with known historical facts lend a great deal of authenticity to the claims of the authors.

MacLeod tradition is that Leod who had possession of Harris and part of Skye, married a daughter of the Norse seneschal of Skye, MacArailt or Harold's son who held Dunvegan and much of Skye.[5] Tradition stated that Leod's two sons, Tormod and Torquil, founded the two main branches of the Clan MacLeod, Siol Tormod and Siol Torquil.[5] Torquil was actually a grandson of Tormod; Torquil's descendants held the lands of the Isle of Lewis until the early seventeenth century when the Mackenzies successfully overthrew the Lewismen,[5] partly with the aid of the Morrisons, and the MacLeods of Harris (Siol Tormod). Younger branches of Siol Torquil held the mainland lands of Assynt and Cadboll longer, and the Isle of Raasay until 1846.[5] Siol Tormod held Harris and Glenelg on the mainland, and also the lands of Dunvegan on the Isle of Skye.[5]

Leod, according to tradition, died around 1280 and was buried on the holy island of Iona, where six successive chiefs of the clan found a last resting-place after him.[6]

14th century

Tormod, son of Leod, does not appear in contemporary records; though according to MacLeod tradition preserved in the 19th century Bannatyne manuscript, he was a noted soldier of his era and was present at the Battle of Bannockburn.[7] Tormod's son and successor, Malcolm, is the first of the clan to appear in contemporary record when both he and his kinsman, Torquil, are recorded as "Malcolme, son to Tormode M'Cloyde",[8] and "Torkyll M'Cloyd",[8] in a royal charter dating to about 1343, during the reign of David II (r. 1329–1371).[9][10][11] Malcolm was succeeded by his eldest child, Iain Ciar, as fourth chief of the clan. R.C. MacLeod dated this event to about 1330. Iain Ciar appears in MacLeod tradition as the most tyrannical chief of the clan; his wife is also said to have been just as cruel as he. Clan tradition states that he was wounded in an ambush on Harris, and soon after died from these wounds at the church at Rodel. R.C. MacLeod dated his death to 1392.[12] Tradition has it that the Lord of the Isles made another attack on Skye in 1395,[13] but Iain's grandson William MacLeod met the MacDonalds at Sligachan (Sligichen)[14] and drove them back to Loch Eynort (Ainort).[13] There they found that their galleys had been moved offshore by the MacAskills,[13] and every invader was killed.[13] The spoils were divided at Creag an Fheannaidh ('Rock of the Flaying')[13] or Creggan ni feavigh ('Rock of the Spoil'),[14] sometimes identified with the Bloody Stone in Harta Corrie.

15th-century clan conflicts

The Battle of Harlaw was fought in 1411 where the MacLeods fought as Highlanders in support of Domhnall of Islay, Lord of the Isles, chief of Clan Donald.[15][16]

The Battle of Bloody Bay was fought in 1481 where the Clan MacLeod supported of John of Islay, Earl of Ross, chief of Clan Donald against his bastard son Angus Og Macdonald. William Dubh MacLeod, chief of Clan MacLeod was killed in the battle.[17]

16th-century clan conflicts

During the 16th-century the Clan MacLeod feuded heavily with the Clan Macdonald of Sleat.[18]

In 1588 William MacLeod of Dunvegan, the 13th chief, bound himself and his heirs in a bond of manrent to "assist, maintain, and defend, and concur with Lachlan Mackintosh of Dunachton, Captain and Chief of the Clan Chattan, and his heirs."[19]

17th century – peace among the clans and Civil War

The Battle of Coire Na Creiche in 1601 on Skye saw the MacLeods defeated by Clan MacDonald of Sleat on the northern slopes of the Cuillin hills.[20] In 1608 after a century of feuding which included battles between the MacDonalds, the Clan Mackenzie and Clan MacLean, all of the relevant Chiefs were called to a meeting with Lord Ochiltree who was the King's representative. Here they discussed the future Royal intentions for governing the Isles. The Chiefs did not agree with the King and were all thrown into prison. Donald the Chief of the Clan MacDonald of Sleat was incarcerated in the Blackness Castle. His release was granted when he at last submitted to the King. Donald died in 1616 and then Donald Gorm Org MacDonald, 9th Chief, 1st Baronet of Sleat, his nephew succeeded as the chief and became the first Baronet of Sleat. Clan MacDonald of Sleat continues to hold title to Trotternish and Sleat on Skye from that day until the present.

During the Civil War, after the Battle of Carbisdale in 1650 the defeated James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose surrendered himself to Neil MacLeod of Assynt at Ardvreck Castle. MacLeod' wife, Christine Munro, tricked Montrose into the castle dungeon and sent for troops of the Covenanter Government,[21] and as a result Montrose was captured and executed.[15]

During the Civil War as many as 500 MacLeods fought as royalists at the Battle of Worcester in 1651.[15]

18th century and Jacobite risings

During the Jacobite rising of 1745 the chief of the Clan MacLeod, Norman MacLeod of Dunvegan, did not support the Jacobites and instead raised several Independent Highland Companies in support of the Government forces.[22] The chief led 500 men of the MacLeod Independent Highland Companies in support of the Government at the Battle of Inverurie, on 23 December 1745, where they were defeated.[22]

The Macleods of Raasay, a branch of the MacLeods of Lewis, fought at the Battle of Culloden as part of the Glengarry Regiment, in retribution, the MacLeods of Dunvegan, under their chief, Norman MacLeod, burned and pillaged the Island of Raasay, harassing its inhabitants for many weeks in the late summer of 1746. As a result, Norman MacLeod became known as "The Wicked Man". In 1745, MacLeod of Dunvegan was said to have been able to "bring out" 700 men.[23]

19th, 20th and 21st centuries

The eldest son of Norman MacLeod of MacLeod (1812–1895), Norman Magnus (1839–1929), succeeded as the 26th chief. The 26th chief died without male issue.[24] Norman MacLeod of MacLeod's second eldest son, Torquil Olave (1841–1857) had earlier died without issue as well.[25] Norman Magnus MacLeod of MacLeod was, therefore, succeeded by Norman MacLeod of MacLeod's third son, Sir Reginald MacLeod of MacLeod (1847–1935), as the 27th chief of Clan MacLeod. Sir Reginald MacLeod of MacLeod had no sons, but two daughters. Dame Flora MacLeod succeeded her father and was followed by her grandson John MacLeod. In 2007, Hugh Magnus MacLeod became the 30th Chief of the Clan MacLeod. For the following events see Chiefs of Clan MacLeod.

Clan societies and parliament

There are nine clan societies affiliated with the Associated Clan MacLeod Societies (ACMS), based in Edinburgh, Scotland. The ACMS is international body which coordinates the nine affiliated national societies around the world. The national societies are Australia (established 1912; re-established 1951), Canada (est. 1936), England (est. 1937), France (est. 1981), Germany (est. 2003), New Zealand (est. 1954), Scotland (est. 1891), South Africa (est. 1960) and The United States of America (est. 1954). Membership to many of these societies are open to anyone who bears the surname Macleod; anyone who is descended from people bearing the surname MacLeod, connected by marriage; anyone who is a member of the septs of the clan; anyone with an interest in the affairs of the clan, whether or not they are related to the MacLeods. In some societies, memberships are available at a price; with yearly memberships to 15 year memberships (Scotland).[26] Every four years members of the national societies gather together at a clan parliament.[26] The last clan parliament was held at the end of July 2014 and took place at Dunvegan.[27]

Castles associated with the clan

Castles that have been owned by the Clan MacLeod have included amongst others:

- Dunvegan Castle, a mile north of the village of Dunvegan on the Skye, dates from the fourteenth century and originally stood on an island.[3] It is the seat of the chief of Clan MacLeod. The castle includes a massive keep or tower, as well as the famous Fairy Tower, as well as a hall block and many more later extensions.[3]

- Cadboll Castle, near Tain, Ross-shire is a now ruinous L-plan tower house.[3] It was originally held by the Clyne family, then the MacLeods of Cadboll, but later passed to the Clan Sinclair.[3]

- Knock Castle (Isle of Skye), also known as Caisteal Camus and Casteal Chamius,[3] was held by the MacLeods in the fifteenth century but later passed to the Clan MacDonald.[3] In 1515, in an attempt to resurrect the Lordship of the Isles the castle was unsuccessfully besieged by Alastair Crotach MacLeod.[3]

- Casteal Mhicleod, near to Shiel Bridge in Lochaber, is a ruinous castle that was once held by Alastair Crotach MacLeod and was still in use in the sixteenth century.[3]

- Dunscaith Castle, also known as Dun Sgathaich, near Armadale, Sleat, Isle of Skye, is a now ruinous castle on a rock by the sea.[3] It was originally held by the MacAskills (a sept of the MacLeods of Lewis),[3] but passed to the MacLeods in the fourteenth century.[3] The MacLeods managed to defend themselves against the MacDonald Lord of the Isles in 1395 and 1401, however the castle passed to the MacDonalds sometime during the fifteenth century.[3]

- Duntulm Castle, near Uig, Skye was built on the site of an Iron Age stronghold and was once held by the MacLeods.[3] In 1540 the castle was visited by James V of Scotland but in the seventeenth century it passed to the MacDonalds.[3]

- Eilean Ghrudidh, Loch Maree, near Kinlochewe, in Wester Ross,[3] is the site of a castle on an island, that was originally held by the MacBeaths in the thirteenth century, but was held by the MacLeods from about 1430 to 1513.[3]

- Gunnery of MacLeod, near to Borve, on the Isle of Berneray, North Uist is the site of a castle once held by the MacLeods.[3] Norman MacLeod of Berneray who was the laird of the island was born there.[3] He was a famous scholar and fought at the Battle of Worcester in 1651.[3]

- See also: Castles of the Clan MacLeod of Lewis.

Clan heirlooms

.jpg)

There are several notable heirlooms belonging to the chiefs of the clan and held at their seat of Dunvegan Castle. Possibly the most well known is the Fairy Flag which has numerous traditions attributed its origins and supposed magical powers. It was said to have had the power, when unfurled, to save the clan on three separate occasions. Another heirloom is a wooden and silver ceremonial cup, known as the Dunvegan Cup, which was made in Ireland and dates back to 1493. The cup is thought to have passed into the possession of the Macleods sometime in the 16th or 17th centuries, during which time the Macleods sent aid to certain Irish chieftains in their warring against English-backed forces. Another heirloom is Sir Rory Mor's Horn, named after the 15th chief of the clan. Clan tradition states that the male heir of the clan must quaff a drink from the horn in one instance.

Clan symbols

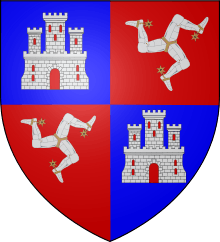

Members of Clan Macleod are entitled to wear a crest badge to show their allegiance to their clan chief. This crest badge contains the heraldic crest and heraldic motto of the clan chief. These elements, like the chief's coat of arms, are the heraldic property of the chief alone.[28] The crest within the crest badge is blazoned a bull's head cabossed sable, horned Or, between two flags gules, staved at the first; and the motto is hold fast.[29] Members of Clan Macleod of The Lewes are entitled to wear a different crest badge, derived from the arms of the chief of that clan.[30]

Members of Clan Macleod may also wear a sprig of juniper, as a clan badge. Clan badges are usually worn on a bonnet behind the crest badge, or attached at the shoulder of a lady's tartan sash.[31]

Clan tartan

| Tartan image | Notes |

|---|---|

.png) | This is possibly the most instantly recognisable Macleod tartan. It is known as MacLeod of Lewis, MacLeod dress, and even "Loud MacLeod". It has no identifiable association with the Lewis Macleods though, and was originally associated with the Dunvegan family. The earliest published appearance of the tartan was in the Vestiarium Scoticum in 1842. The Vestiarium, composed and illustrated by the dubious 'Sobieski Stuarts', is the source for many of today's "clan tartans". The Vestiarium has also been proven to be a forgery and a Victorian hoax. The tartan was described by Sir Thomas Dick Lauder, in a letter to Sir Walter Scott in 1829: "MacLeod (of Dunvegan) has got a sketch of this splendid tartan, three black stryps upon ain yellow fylde". It is thought that the Macleod chief was a good friend of the Sobieski Stuarts who gave him the sketch of the tartan years before they published their forgery.[32] One contemporary critic of the Vestiarium even likened the Macleod tartan to that of a horse blanket.[33]

Today, the tartan is registered with the Scottish Tartans Authority and the Scottish Tartans World Register (both under #1272) with the symmetrical treadcount “K32Y4K32Y48R4” and with a color palette of black 101010, freedom red C80000, and golden poppy D8B000.[34] |

.png) | This tartan is sometimes known as MacLeod hunting or MacLeod of Harris.[35] It was published in several early collections of tartan such as Logan's The Scottish Gael (1831) and Smibert's (1851). The tartan is derived from the Mackenzie tartan used by John Mackenzie in 1771, when he raised the regiment known as "Lord Macleod's Highlanders". The Mackenzies claimed to be heirs to the chiefship of the Macleods of Lewis, after the death of Roderick in 1595. The tartan was approved by Norman Magnus, 26th chief of Clan Macleod. It was adopted by the clan society in 1910.[36]

Today, the tartan is registered with the Scottish Tartans Authority and the Scottish Tartans World Register (both under #1583) with the symmetrical treadcount “R6K4G30K20BL40K4Y8” and with a color palette of black 101010, freedom red C80000, golden poppy E8C000, green 006818, and denim blue 1474B4.[37] |

Clan chiefs

Clan septs

Septs are clans or families who were under the protection of a more powerful clan or family. Scottish clans were largely collections of different families who held allegiance to a common chief. The following names, according to the Associated Clan MacLeod Societies, are attributed as septs of Clan Macleod (of Dunvegan and Harris); there are also a number of other septs attributed to Clan Macleod of The Lewes.[38]

| Names | Notes |

|---|---|

| Beaton, Betha, Bethune, Beton.[38] | There is also an independent Clan Bethune. |

| Harald, Haraldson, Harold, Harrell, Harrold, Herrald, MacHarold, MacRalte, MacRaild.[38] | |

| Andie, MacAndie, McCaskill, MacHandie, MacKande, MacKandy, Makcandy.[38] | |

| MacCaig, MacCoig, MacCowig, MacCrivag, MacCuaig, MacKaig, MacQuigg.[38] | |

| MacAlear, MacClewer, McClure, MacClure, MacLeur, MacLewer, MacLewis, Lewis, MacLur, MacLure, Clure, Cluer, Clewer.[38] | |

| Cremmon, Crimmon, Griman, Grimman, Grimmond, MacCrimmon, MacCrummen, MacGrimman, MacGrymmen, MacRimmon.[38] | See MacCrimmon (piping family). |

| MacKilliam, MacKullie, MacWilliam, MacWilliams, MacWillie, MacWylie, McCullie, Williamson.[38] | Also attributed to Clan Gunn.[39] |

| Norman, Normand, Norris, Norval, Norwell, Tormud.[38] |

In fiction

The Clan MacLeod is featured prominently in the Highlander franchise, with four major characters - Connor, Duncan, Colin and Quentin MacLeod - all being members.

See also

- Clan MacLeod of Lewis, a separate branch traditionally centred on the Isle of Lewis.

- MacCrimmon (piping family), hereditary pipers to the chiefs of Clan MacLeod.

- MacLeod, Scott GK. 2011. - MacLeod Piping Stories and Traditions and some of PM Donald MacLeod's Bagpipe Music. Academia.edu

Notes

- 1 2 3 Mac an Tàilleir, Iain. "Ainmean Pearsanta" (docx). Sabhal Mòr Ostaig. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ↑ "Aussie builder claims MacLeod chief status". The Herald. 17 Mar 2007. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Coventry, Martin. (2008). Castles of the Clans: The Strongholds and Seats of 750 Scottish Families and Clans. pp. 390–392. ISBN 978-1-899874-36-1.

- ↑ A Dictionary of English Surnames, p.292.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Highland Clans, p.171-174.

- ↑ Nicolson, Alexander; Maclean, Alasdair (1994). History of Skye: a record of the families, the social conditions and the literature of the island. Maclean Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-9516022-7-0.

- ↑ MacLeod, Roderick Charles (1927). The MacLeods of Dunvegan. Edinburgh: Privately printed for the Clan MacLeod Society. pp. 33–34.

- 1 2 Robertson, William (1798). An index, drawn up about the year 1629, of many records of charters, granted by the different sovereigns of Scotland between the years 1309 and 1413, most of which records have been long missing. With an introduction, giving a state, founded on authentic documents still preserved, of the ancient records of Scotland, which were in that kingdom in the year 1292. To which is subjoined, indexes of the persons and places mentioned in those charters, alphabetically arranged. Edinburgh: Printed by Murray & Cochrane. p. 48.

- ↑ Dewar, Peter Beauclerk (2001). Burke's landed gentry of Great Britain: together with members of the titled and non-titled contemporary establishment (19, illustrated ed.). Burke's Peerage & Gentry. p. 941. ISBN 978-0-9711966-0-5.

- ↑ Matheson, William (1979). "The MacLeods of Lewis". macleodgenealogy.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ↑ "Malcolm Gillecaluim Macleod (III Chief)". macleodgenealogy.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- ↑ MacLeod, Roderick Charles (1927). The MacLeods of Dunvegan. Edinburgh: Privately printed for the Clan MacLeod Society. pp. 51–55.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marsh, Terry (2009). The Isle of Skye. Cicerone Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-85284-560-5.

- 1 2 Burke, John (1838). "A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland Enjoying Territorial Possessions Or High Official Rank: But Uninvested with Heritable Honours, John Burke". 3. Colburn: 477.

- 1 2 3 Way, George and Squire, Romily. Collins Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia. (Foreword by The Rt Hon. The Earl of Elgin KT, Convenor, The Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs). Published in 1994. Pages 242 - 245.

- ↑ The MacLeods of Dunvegan by Rev. Canon R.C MacLeod of Macleod. p. 63 to 64

- ↑ MacLeod History electricscotland.com. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ↑ Roberts, John Leonard. (1999). Feuds, Forays and Rebellions: History of the Highland Clans, 1475–1625. (illustrated ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 0-7486-6244-8.

- ↑ The Celtic magazine; a monthly periodical devoted to the literature, history, antiquities, folk lore, traditions, and the social and material interests of the Celt at home and abroad (Volume 11) p.166

- ↑ Roberts, John Leonard (1999). Feuds, Forays and Rebellions: History of the Highland Clans, 1475–1625. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 140–1. ISBN 978-0-7486-6244-9.

- ↑ "MacLeod of Raasay Clan". www.scotsconnection.com. Retrieved 29 January 2008.

- 1 2 MacLeod, Ruairi. (1984). Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness. Volume LIII. pp. 318 - 320.

- ↑ "The Scottish Clans and Their Tartans”. W. & A. K. Johnston Limited. Edinburgh and London. 1886. Page 65.

- ↑ "Norman Magnus MACLEOD (XXVI Chief)". macleodgenealogy.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ↑ "Torquil Olave MACLEOD". macleodgenealogy.org. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- 1 2 "The Records of the Clan MacLeod Society of America". lib.odu.edu. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ↑ "Clan Parliament 2014". clanmacleod.org. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ↑ "Crests". The Court of the Lord Lyon. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ↑ Way of Plean 2000: p. 216.

- ↑ "Arms and Tartans". clanmacleod.org. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ↑ Adam; Innes of Learney (1970): p. 541–543.

- ↑ "Tartan Details – MacLeod of Lewis (VS)". Scottish Register of Tartans. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ↑ Stewart, Donald C.; Thompson, J Charles (1980). Scotland's Forged Tartans, An analytical study of the Vestiarium Scoticum. Edinburgh: Paul Harris Publishing. pp. 83–84. ISBN 0-904505-67-7.

- ↑ The Scottish Register of Tartans - MacLeod of Lewis (Vestiarium Scotorum) Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. tartanregister.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ "Tartan – MacLeod/ Macleod of Harris (WR583)". Scottish Tartans World Register. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ↑ "Tartan Details – MacLeod No. 4". Scottish Register of Tartans. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ↑ Scot Web - Tartan Mill scotweb.co.uk. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "MacLeod Septs". clanmacleod.org. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ↑ "Septs of Clan Gunn". clangunn.us. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

Sources

- Adam, Frank; Innes of Learney, Thomas (1970). The Clans, Septs & Regiments of the Scottish Highlands (8th ed.). Edinburgh: Johnston and Bacon.

- Moncreiffe of that Ilk, Iain (1967). The Highland Clans. London: Barrie & Rocklif.

- Reaney, Percy Hilde; Wilson, Richard Middlewood (2006). A Dictionary of English Surnames (3rd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-99355-1.

- Stewart, Donald Calder; Thompson,, J. Charles (1980). Scarlett, James, ed. Scotland's Forged Tartans. Edinburgh: Paul Harris Publishing. ISBN 0-904505-67-7.

- Stewart, Donald Calder (1974). The Setts of the Scottish Tartans, with descriptive and historical notes (2nd revised ed.). London: Shepheard-Walwyn Publishers. ISBN 0-85683-011-9.

- Way of Plean, George; Squire, Romilly (2000). Clans & Tartans. Glasgow: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-472501-8.

External links

- http://www.clanmacleod.org/ – Associated Clan MacLeod Societies

- http://www.macleodgenealogy.org/ – Associated Clan MacLeod Societies

- http://www.clan-macleod-scotland.org.uk/ - Clan MacLeod Society of Scotland