Sectarian violence in Iraq (2006–08)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Between 2006 and 2008, Iraq experienced a high level of sectarian violence. Some scholars and journalists state that the country was experiencing a civil war.[16]

Following the U.S.-launched 2003 invasion of Iraq, intercommunal violence between Iraqi Sunni and Shi'a factions became prevalent. In February 2006, the Sunni organization Al-Qaeda in Iraq bombed one of the holiest sites in Shi'a Islam - the al-Askari Mosque in Samarra. This set off a wave of Shi'a reprisals against Sunnis followed by Sunni counterattacks.[17] The conflict escalated over the next several months until by 2007, the National Intelligence Estimate described the situation as having elements of a civil war.[18] In 2008 and 2009, during the Sunni Awakening and the surge, violence declined dramatically.[19][20] However, low-level strife continued to plague Iraq until the U.S. withdrawal in late 2011.[16]

Two polls of Americans conducted in 2006 found that between 65% to 85% believed Iraq was in a civil war;[21][22] however, a similar poll of Iraqis conducted in 2007 found that 61% did not believe that they were in a civil war.[23]

In October 2006, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Iraqi government estimated that more than 370,000 Iraqis had been displaced since the 2006 bombing of the al-Askari Mosque, bringing the total number of Iraqi refugees to more than 1.6 million.[24] By 2008, the UNHCR raised the estimate of refugees to a total of about 4.7 million (~16% of the population). The number of refugees estimated abroad was 2 million (a number close to CIA projections[25]) and the number of internally displaced people was 2.7 million.[26] The estimated number of orphans across Iraq has ranged from 400,000 (according to the Baghdad Provincial Council), to five million (according to Iraq's anti-corruption board). A UN report from 2008 placed the number of orphans at about 870,000.[27][28] The Red Cross stated in 2008 that Iraq's humanitarian situation was among the most critical in the world, with millions of Iraqis forced to rely on insufficient and poor-quality water sources.[29]

According to the Failed States Index, produced by Foreign Policy magazine and the Fund for Peace, Iraq was one of the world's top 5 unstable states from 2005 to 2008.[30] A poll of top U.S. foreign policy experts conducted in 2007 showed that over the next 10 years, just 3% of experts believed the U.S. would be able to rebuild Iraq into a "beacon of democracy" and 58% of experts believed that Sunni–Shiite tensions would dramatically increase in the Middle East.[31][32]

Ethno-sectarian composition

The population of Iraq can be divided into several main ideological or ethnic strands:

- Shias (Arabic speaking): 55-65%: A majority of the population.

- Sunnis (Arabic speaking): 20%: Politically dominated Iraq for centuries until the Coalition invasion of 2003.

- Kurdish - 26%: independent administration (mostly Sunnis, small Shi'ite, Yazidi, and other elements).

- Assyrian - 1%: This group has a minor role in the current situation (mostly Christians).

- Turkoman - 2%: This group has a minor role in the current situation (majority Sunni with large Shi'a minority), although Turkey is concerned about their overall treatment in Iraq.

Religions:

- Islam - 95%: This is the primary religion in Iraq and serves as one of the primary sectarian distinctions.

- Christian, Mandaeans and Yazidi ~ 5% : These groups have a minor role in the civil war situation.

The main two participants in the violence were the Arab Sunni and Arab Shia factions, but conflicts within a single group also occurred. The Kurds were caught between the two religious groups, but as they were an ethnicity as opposed to a religious movement, they were often at odds with the Arabs that were settled in Iraqi Kurdistan by Saddam's Arabization policy.[33] Blurring this cohesion, though, were division of social, economic, political and geographic identities.

Participants

A multitude of groups formed the Iraqi insurgency, which arose in a piecemeal fashion as a reaction to local events, notably the realisation of the U.S. military’s inability to control Iraq.[34] Beginning in 2005 the insurgent forces coalesced around several main factions, including the Islamic Army in Iraq and Ansar al-Sunna.[35] Religious justification was used to support the political actions of these groups, as well as a marked adherence to Salafism, branding those against the jihad as non-believers. This approach played a role in the rise of sectarian violence.[36] The U.S. military also believe that between 5-10% of insurgent forces are non-Iraqi Arabs.[34]

Independent Shi'ite militias identified themselves around sectarian ideology and possessed various levels of influence and power. Some militias were founded in exile and returned to Iraq only after the toppling of Saddam Hussein, such as the Badr Organization. Others were created since the state collapse, the largest and most uniform of which was the Mahdi Army established by Moqtada al-Sadr and believed to have around 50,000 fighters.[34]

Conflict and tactics

Non-military targets

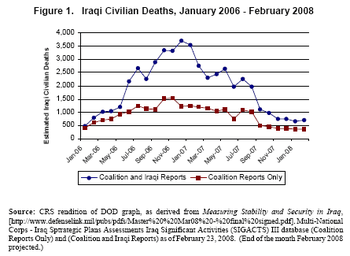

Attacks on non-military and civilian targets began in earnest in August 2003 as an attempt to sow chaos and sectarian discord. Iraqi casualties increased over the next several years.[37][38]

Bomb and mortar attacks

Bomb attacks aimed at civilians usually targeted crowded places such as marketplaces and mosques in Shi'ite cities and districts.[39][40] The bombings, which were sometimes co-ordinated, often inflicted extreme casualties.

For example, the 23 November 2006 Sadr City bombings killed at least 215 people and injured hundreds more in the Sadr City district of Baghdad, sparking reprisal attacks, and the 3 February 2007 Baghdad market bombing killed at least 135 and injured more than 300. The co-ordinated 2 March 2004 Iraq Ashura bombings (including car bombs, suicide bombers and mortar, grenade and rocket attacks) killed at least 178 people and injured at least 500.

Suicide bombings

Since August 2003, suicide car bombs were increasingly used as weapons by Sunni militants, primarily al-Qaeda extremists. The car bombs, known in the military as vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIEDs), emerged as one of the militants' most effective weapons, directed not only against civilian targets but also against Iraqi police stations and recruiting centers.

These vehicle IEDs were often driven by the extremists from foreign Muslim countries with a history of militancy, such as Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Egypt, and Pakistan.[41]

Death squads

Death squad-style killings in Iraq took place in a variety of ways. Kidnapping, followed by often extreme torture (such as drilling holes in people's feet with drills[42]) and execution-style killings, sometimes public (in some cases, beheadings), emerged as another tactic. In some cases, tapes of the execution were distributed for propaganda purposes. The bodies were usually dumped on a roadside or in other places, several at a time. There were also several relatively large-scale massacres, like the Hay al Jihad massacre in which some 40 Sunnis were killed in a response to the car bombing which killed a dozen Shi'ites.

The death squads were often disgruntled Shi'ites, including members of the security forces, who killed Sunnis to avenge the consequences of the insurgency against the Shi'ite-dominated government.[43]

Attacks on places of worship

On 22 February 2006, a highly provocative explosion took place at the al-Askari Mosque in the Iraqi city of Samarra, one of the holiest sites in Shi'a Islam, believed to have been caused by a bomb planted by al-Qaeda in Iraq. Although no injuries occurred in the blast, the mosque was severely damaged and the bombing resulted in violence over the following days. Over 100 dead bodies with bullet holes were found on the next day, and at least 165 people are thought to have been killed. In the aftermath of this attack the U.S. military calculated that the average homicide rate in Baghdad tripled from 11 to 33 deaths per day.[34]

Dozens of Iraqi mosques were aftwerwards attacked or taken over by the sectarian forces. For example, a Sunni mosque was burnt in the southern Iraqi town of Haswa on 25 March 2007, in the revenge for the destruction of a Shia mosque in the town the previous day.[44] In several cases, Christian churches were also attacked by the extremists. Later, another al-Askari bombing took place in June 2007.

Iraq's Christian minority also became a target by Al Qaeda Sunnis because of conflicting theological ideas.[45][46]

Sectarian desertions

Some Iraqi service members deserted the military or the police and others refused to serve in hostile areas.[47] For example, some members of one sect refused to serve in neighborhoods dominated by other sects.[47] The ethnic Kurdish soldiers from northern Iraq, who were mostly Sunnis but not Arabs, were also reported to be deserting the army to avoid the civil strife in Baghdad.[48]

Timeline

For more information on events in a specific year, see the associated timeline page.

Growth in refugee flight

By 2008, the UNHCR raised the estimate of refugees to a total of about 4.7 million, with 2 million displaced internally and 2.7 million displaced externally.[26] In April 2006 the Ministry of Displacement and Migration estimated that "nearly 70,000 displaced Iraqis, especially from the capital, are living in deteriorating conditions,” due to ongoing sectarian violence.[49] Roughly 40% of Iraq's middle class is believed to have fled, the U.N. said. Most were fleeing systematic persecution and had no desire to return.[50] Refugees were mired in poverty as they were generally barred from working in their host countries.[51][52] A 25 May 2007 article noted that in the past seven months only 69 people from Iraq had been granted refugee status in the United States.[53]

Use of "civil war" label

The use of the term "civil war" has been controversial, with a number of commentators preferring the term "civil conflict". A poll of over 5,000 Iraqi nationals found that 27% of polled Iraqi residents agreed that Iraq was in a civil war, while 61% thought Iraq was not.[23] Two similar polls of Americans conducted in 2006 found that between 65% to 85% believed Iraq was in a civil war.[21][22]

In the United States, the term has been politicized. Deputy leader of the United States Senate, Dick Durbin, referred to "this civil war in Iraq"[54] in a criticism of George W. Bush's 10 January 2007, President's Address to the Nation.[55]

Edward Wong on 26 November 2006 paraphrased a report from a group of American professors at Stanford University that the insurgency in Iraq amounted to the classic definition of a civil war.[56]

An unclassified summary of the 90-page January 2007 National Intelligence Estimate, titled Prospects for Iraq's Stability: A Challenging Road Ahead, states the following regarding the use of the term "civil war":

- The Intelligence Community judges that the term “civil war” does not adequately capture the complexity of the conflict in Iraq, which includes extensive Shia-on-Shia violence, al-Qa’ida and Sunni insurgent attacks on Coalition forces, and widespread criminally motivated violence. Nonetheless, the term “civil war” accurately describes key elements of the Iraqi conflict, including the hardening of ethno-sectarian identities, a sea change in the character of the violence, ethno-sectarian mobilization, and population displacements.[57]

Retired United States Army General Barry McCaffrey issued a report on 26 March 2007, after a trip and analysis of the situation in Iraq. The report labeled the situation a "low-grade civil war."[58] In page 3 of the report, he writes that:

- "Iraq is ripped by a low-grade civil war which has worsened to catastrophic levels with as many as 3000 citizens murdered per month. The population is in despair. Life in many of the urban areas is now desperate. A handful of foreign fighter (500+)--and a couple thousand Al Qaeda operatives incite open factional struggle through suicide bombings which target Shia holy places and innocent civilians...The police force is feared as a Shia militia in uniform which is responsible for thousands of extra-judicial killings."

See also

- Casualties of the conflict in Iraq since 2003

- Historical Shi'a-Sunni relations

- Iraqi insurgency

- Post-invasion Iraq, 2003–present

- Refugees of Iraq

Events:

- 2 March 2004 Iraq Ashura bombings

- 23 November 2006 Sadr City bombings

- 22 January 2007 Baghdad bombings

- 3 February 2007 Baghdad market bombing

- Hay al Jihad massacre

General:

Films

- Iraq in Fragments, documentary (2006)

References

- ↑ Anthony H. Cordesman (2011), "Iraq: Patterns of Violence, Casualty Trends and Emerging Security Threats", p. 33.

- ↑ Iraq Body Count. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- ↑

- International Crisis Group: "Iraq’s Civil War, the Sadrists and the Surge". Released on 7 February 2008.

- The Costs of Containing Iran. Nasr, Vali and Takeyh, Ray (Jan/Feb 2008).

to preserve the territorial integrity of Iraq and prevent the civil war there from engulfing the Middle East.

- International Crisis Group: "Iraq after the Surge I: The New Sunni Landscape". Released on 30 April 2008.

- ↑ "U.K. Finishes Withdrawal of Its Last Combat Troops in Iraq". Bloomberg. 26 May 2009.

- ↑ "Iraq Government Vows to Disband Sunnis". Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ The Brookings Institution Iraq Index: Tracking Variables of Reconstruction & Security in Post-Saddam Iraq. 1 October 2007

- ↑ Pincus, Walter (17 November 2006). "Violence in Iraq Called Increasingly Complex". The Washington Post. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ Ricks, Thomas E. "Intensified Combat on Streets Likely". The Washington Post. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ Page 2

- ↑ "Using that self aggrandizing, self appointed title, al Hassan built up a force of a thousand men" The Hidden Imam's Dream - Sky News, 30 January 2007

- ↑ "June deadliest month for U.S. troops in 2 years". USATODAY.COM. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ "Private contractors outnumber U.S. troops in Iraq". By T. Christian Miller. Los Angeles Times. 4 July 2007.

- ↑ "Contractor deaths add up in Iraq". By Michelle Roberts. Deseret Morning News. 24 February 2007.

- ↑ Collins, C. (19 August 2007) "U.S. says Iranians train Iraqi insurgents," McClatchy Newspapers

- ↑ "A Dark Side to Iraq 'Awakening' Groups". Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- 1 2 "Car Bomb Epidemic Is the New Normal in Iraq". New York Times. 3 September 2013.

- ↑ Kenneth Katzman (2009). Iraq: Post-Saddam Governance and Security. Congressional Research Service. p. 29. ISBN 9781437919448.

- ↑ "Elements of 'civil war' in Iraq". BBC News. 2 February 2007. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

A US intelligence assessment on Iraq says "civil war" accurately describes certain aspects of the conflict, including intense sectarian violence.

- ↑ "Iraq: Patterns of Violence, Casualty Trends and Emerging Security Threats" (PDF). Center for Strategic & International Studies. 9 February 2011. p. 14. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ↑ Kenneth Pollack (July 2013). "The File and Rise and Fall of Iraq" (PDF). Brookings Institution. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- 1 2 "Poll: Nearly two-thirds of Americans say Iraq in civil war". Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- 1 2 12/06 CBS: 85% of Americans now characterize the situation in Iraq as a Civil War

- 1 2 Colvin, Marie (18 March 2007). "Iraqis: life is getting better". London: The Times. Retrieved 30 April 2010.[]

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees". UNHCR. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ "CIA World Factbook: Iraq". Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- 1 2 UNHCR - Iraq: Latest return survey shows few intending to go home soon. Published 29 April 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ↑ 5 million Iraqi orphans, anti-corruption board reveals English translation of Aswat Al Iraq newspaper 15 December 2007

- ↑ ""Draft law seeks to provide Iraqi orphans with comprehensive support" by Khalid al-Tale, 27 March 2012". Mawtani. 27 March 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ "Iraq: No let-up in the humanitarian crisis". Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑

- "Failed States list 2005". Fund for Peace. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- "Failed States list 2006". Fund for Peace. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- "Failed States list 2007". Fund for Peace. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- "Failed States list 2008". Fund for Peace. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- ↑ U.S. foreign policy experts oppose surge

- ↑ Foreign Policy: Terrorism Survey III (Final Results)

- ↑ "US exit may lead to Iraqi civil war". 19 November 2003

- 1 2 3 4 Dodge, Toby (2007). "The Causes of US Failure in Iraq". Survival. 49 (1): 85–106. doi:10.1080/00396330701254545.

- ↑ "In Their Own Words: Reading the Iraqi Insurgency". International Crisis Group. 15 February 2006.

- ↑ Meijer, Roel. "The Sunni Resistance and the Political Process". In Bouillion, Markus; Malone, David; Rowsell, Ben. Preventing Another Generation of Conflict. Lynne Rienner.

- ↑ Administrative User (7 January 2013). "Johns Hopkins School of Public Health: Iraqi Civilian Deaths Increase Dramatically After Invasion". Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ Max Boot (3 May 2008). "Wall Street Journal: The Truth About Iraq's Casualty Count". WSJ. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ AFP: Bomb attack kills more than 40 near Iraq Shiite shrine

- ↑ "CNN: Pair of bombs kills 53 in Baghdad, officials say". Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ Bradley Graham (9 May 2005). "U.S. Shifting Focus to Foreign Fighters" (PDF). Washington Post. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

U.S. and Iraqi authorities say suicide drivers are invariable foreign fighters. Officers here said they knew of no documented case in which a suicide attacker turned out to have been an Iraqi.

- ↑ http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/article737635.ece%5B%5D

- ↑ "Iraq 'death squad caught in act'". BBC. 16 February 2006. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ↑ "Al Jazeera English - News - Iraq Mosque Burnt In Revenge Attack". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ "BBC Analysis: Iraq's Christians under attack". Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ http://www.thenational.ae/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20100320/MAGAZINE/703199980/1298/MAGAZINE1

- 1 2 Former CIA Officer Says Iraq Can Be Stabilized By Trained Security Forces PBS

- ↑ "Kurdish Iraqi Soldiers Are Deserting to Avoid the Conflict in Baghdad". Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ John Pike. "IRAQ: Sectarian violence continues to spur displacement". Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ "40% of middle class believed to have fled crumbling nation". SFGate. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ "Doors closing on fleeing Iraqis". Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ "Displaced Iraqis running out of cash, and prices are rising". SFGate. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ Ann McFeatters: Iraq refugees find no refuge in America. Seattle Post-Intelligencer 25 May 2007

- ↑ Susan Milligan, "Democrats say they will force lawmakers to vote on increase". 11 July 2006

- ↑ "President's Address to the Nation". 10 January 2007. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ Wong, Edward (26 November 2006). "Scholars agree Iraq meets definition of 'civil war'". The New York Times. International Herald Tribune.

- ↑ "Prospects for Iraq's Stability: A Challenging Road Ahead (PDF)" (PDF). National Intelligence Estimate. January 2007.

- ↑ http://www.defensetech.org/archives/Iraq%20After%20action.pdf

Bibliography

- Iraq Study Group, The Iraq Study Group Report: The Way Forward - A New Approach (2006)

- Nir Rosen, In the Belly of the Green Bird: The Triumph of the Martyrs in Iraq (2006)

External links

- Refugees Report "The Iraqi Displacement Crisis" March 2008.

- United States Dept. of Homeland Security Fact Sheet on admitting Iraqi refugees to the United States March 2008.

- Sami Ramadani interview "Iraq is not a civil war" Spring 2007.

- Taheri, Amir. "There is no Civil War in Iraq, Gulf News, 6 December 2006.

- Phillips, David L., "Federalism can prevent Iraq civil war", 20 July 2005.

- Hider, James, "Weekend of slaughter propels Iraq towards all-out civil war", 18 July 2005.

- Ramadani, Sami, "Occupation and Civil War", UK Guardian, 8 July 2005.

- Phelps, Timothy M., "Experts: Iraq Verges on Civil War". Newsday, 12 May 2005.

- Strobel, Warren P., and Jonathan S. Landay, "CIA Officers Warn of Iraq Civil War, Contradicting Bush's Optimism", Knight-Ridder, 22 January 2004.

- "US exit may lead to Iraqi civil war", 19 November 2003.

- Dunnigan, James, "The Coming Iraqi Civil War", 4 April 2003