Red brick university

Red brick university (or redbrick university) is a term originally used to refer to eight or nine civic universities founded in the major industrial cities of England in the 19th century,[1] although it is sometimes restricted to only those six that achieved independent university status prior to the first world war.[3] The term is now used more broadly to refer to British universities founded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in major cities.[4] Six of the original redbrick institutions, or their predecessor institutes, gained university status before World War I and were initially established as civic science or engineering colleges.[5][6][7][8][9][10]

Whilst the term was originally coined as these institutions were new and thus regarded by the ancient universities as arriviste,[11] the description has since ceased to be derogatory with the 1960s proliferation of universities and the reclassification of polytechnics in 1992. Eight of the nine institutions are members of the Russell Group (which receives two-thirds of all research grant funding in the United Kingdom).[12]

Origins of the term and use

The term red brick or redbrick was first coined by Edgar Allison Peers, a professor of Spanish at the University of Liverpool, to describe the civic universities (under the pseudonym "Bruce Truscot" in his 1943 book Redbrick University).[13] Although Peers used red brick in the title of the original book, he used redbrick adjectivally in the text and in the title of the 1945 sequel. He is said to have later regretted his use of red brick in the title.[14]

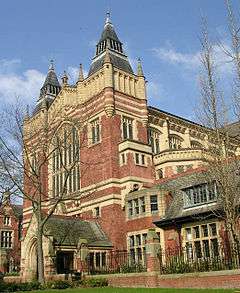

Peers' reference was inspired by the fact that The Victoria Building at the University of Liverpool (designed by Alfred Waterhouse and completed in 1892 as the main building for University College, Liverpool) is built from a distinctive red pressed brick, with terracotta decorative dressings.[15] On this basis the University of Liverpool claims to be the original "red brick" institution, although the titular, fictional Redbrick University was a cipher for all the civic universities of the day.[16][17][18]

While the University of Liverpool was an inspiration for the "red brick" university alluded to in Peers' book, receiving university status in 1903, the University of Birmingham was the first of the civic universities to gain independent university status in 1900 and the University has stated that the popularity of the term "red brick" owes to its own Chancellor's Court, constructed from Accrington red brick.[19][20] The University of Birmingham grew from the Mason Science College (opened two years before University College Liverpool in 1880), an elaborate red brick and terracotta building in central Birmingham which was demolished in 1962.[21]

Civic university movement

These universities were distinguished by being non-collegiate institutions that admitted men without reference to religion or background and concentrated on imparting to their students "real-world" skills, often linked to engineering.[22] In this sense they owed their structural heritage to the Humboldt University of Berlin, which emphasised practical knowledge over the academic sort.[23] This focus on the practical also distinguished the red brick universities from the ancient English universities of Oxford and Cambridge and from the newer (although still pre-Victorian) University of Durham, collegiate institutions which concentrated on divinity and the liberal arts, and imposed religious tests (e.g. assent to the Thirty-Nine Articles) on staff and students. Scotland's ancient universities (St Andrews, Glasgow, Aberdeen and Edinburgh) were founded on a different basis between 1400 and 1600.[24]

The first wave of large civic red brick universities all gained official university status before the First World War, all of these institutions have origins dating back to older medical or engineering colleges and were located in the industrial centres of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras that required strong scientific and technical workforces.[24] These universities developed out of various 19th-century private research and education institutes in industrial cities. The 1824 Manchester Mechanics' Institute formed the basis of the Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST), and thus led towards the current University of Manchester formed in 2004.[9] The University of Birmingham has origins dating back to the 1825 Birmingham Medical School.[5] The University of Leeds also owes its foundations to a medical school: the 1831 Leeds School of Medicine. The University of Bristol began with the 1876 University College, Bristol,[6] the University of Liverpool with a University College in 1881,[8] and the University of Sheffield with a medical school in 1828, Firth College in 1879 and a technical school in 1884, which merged to form a university college in 1897.[10][25] Of the redbricks that gained independent university status later, Newcastle owed its beginnings to a medical school established in 1834 and affiliated to Durham University from 1852, and a college of science established, in partnership with Durham, in 1871.[26] Reading was established as an extension college by Oxford University in 1892, incorporating pre-existing schools of art and science,[27] while Nottingham was established as a civic college in 1881.[28] All of the redbricks, with the exception of Reading, were non-residential, in contrast to Oxford, Cambridge and Durham.

Combined English Universities was a university constituency in the UK Parliament created by the Representation of the People Act 1918 for graduates of Durham University and the six pre-WWI red bricks. Graduates of Oxford, Cambridge, and London had already been enfranchised and graduates of the University of Wales were enfranchised at the same time. Reading University was added to the Combined English Universities constituency in 1928 (prior to this its graduates, taking London degrees, would have joined the London constituency). The constituency was abolished in 1950.

| Name | University charter awarded | Predecessor institutions | Image | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victoria University | 1880 (defunct 1903) |

Owens College, Manchester (1851)[29] Royal School of Medicine and Surgery, Manchester (1824)[29] Leeds School of Medicine (1831)[30] Yorkshire College of Science (1874)[30] University College Liverpool (1881) |

The Victoria University was a federal university based in Manchester with colleges in Manchester, Leeds and Liverpool. It was defunct by 1903 as the colleges sought independent university status, leading to the formation of the Victoria University of Manchester from the merger of the Victoria University with Owens College, Manchester, in 1903. This new institution later merged with UMIST to form the University of Manchester in 2004. | |

| University of Birmingham | 1900 | Birmingham Medical School (1825) Mason Science College (1875) Mason University College (1898) |

|

The first independent civic university to be awarded full university status by Royal Charter. |

| University of Liverpool | 1903 | University College, Liverpool (1881) |  |

|

| University of Manchester | 1903 (as Victoria University of Manchester) 2004 (as University of Manchester) |

Victoria University of Manchester (1903) (Royal School of Medicine and Surgery, Manchester (1824), Owens College, Manchester (1851), Victoria University (1880)) UMIST (1956) (Mechanics' Institute, Manchester (1824), Manchester Technical School (1883))[31] |

|

The federal Victoria University existed between 1880-1903. The Victoria University of Manchester was granted a royal charter as its successor institution in 1903 and merged with Owens College, which had previously merged with the Royal School of Medicine and Surgery in 1872. The Manchester Mechanics' Institute, formed in 1824, became the Manchester Technical School in 1884 and then UMIST in 1956; it merged with the Victoria University of Manchester in 2004 to form the current University of Manchester. |

| University of Leeds | 1904 | Leeds School of Medicine (1831) Yorkshire College of Science (1874) |

|

Yorkshire College of Science became Yorkshire College then merged with the School of Medicine in 1884. Part of the Victoria University from 1886 to 1903.[30] |

| University of Sheffield | 1905 | Sheffield Medical School (1828) Firth College (1879) Sheffield Technical School (1884) University College of Sheffield (1897) |

|

|

| University of Bristol | 1909 | University College Bristol (1876) |  |

|

| University of Reading | 1926 | University College Reading (1892) |  |

|

| University of Nottingham | 1948 | University College Nottingham (1881) |  |

|

| Newcastle University | 1963 | Newcastle upon Tyne College of Medicine (later Durham University College of Medicine) (1834); Durham College of Science (later Armstrong College) (1871); Merged to form King's College (1937) |

.jpg) |

Truscot states in Red Brick that "[Durham's] Newcastle college, perhaps, can properly find a place in this survey"[2] |

Other institutions

Various other civic institutions with origins dating from the 19th and early to mid-20th centuries have also been described as Red Brick. According to historian William Whyte of the University of Oxford, Truscott's original definition includes the University of Dundee (originally an independent university college, before becoming a constituent college of the University of St Andrews), Newcastle University (previously a college of the University of Durham, and noted by Truscot as "perhaps" being included), and the Welsh university colleges (not named, but could include Aberystwyth (1872), Cardiff (1883), Bangor (1885) and possibly Swansea (1920)). Notably, Whyte does not include Reading or Nottingham, which Truscot lists in his second edition.[2][32]

Many other institutions share similar characteristics to the original civic universities, namely those in the second wave of civic universities before the advent of the plate glass universities in 1961. These universities differed from the red bricks in that they evolved from local university colleges rather than civic institutes and all (except Keele) previously awarded external degrees of the University of London before being granted full university status after the First World War. The Robbins Report lists Reading, Nottingham, Southampton, Hull, Exeter, Leicester and Keele as being "younger civic universities".[33] Of these, the University of Reading, founded in the late 19th century as an extension college of Oxford University and the only university to receive its charter between the two world wars, describes itself as a "red brick" university.[34][35]

Queen's University Belfast gained university status in 1908 during the same period as the English red brick universities, having previously been established in 1845 as a college of the Queen's University of Ireland (later Royal University of Ireland). As a result it meets the dictionary definition of a red brick university,[4] and is sometimes named as such.[36]

Department for Education research in 2016 split universities into four categories: ancient (pre-1800), red brick (1800–1960), plate glass (1960-1992), and post-1992.[37] The term "red brick" is also sometimes used more widely to mean any of the non-ancient universities. Usage in The Spectator has taken in Birkbeck, University of London and the universities of Brunel, Hull, Sussex, Nottingham and Westminster, the last a former polytechnic.[38]

See also

- Ancient universities

- Ancient universities of Scotland

- Campus university

- New universities

- Plate glass university

- Sandstone universities (Australia)

References

- ↑ It was coined by Bruce Truscot (Edgar Allison Peers) in Red Brick University, which states: "It is primarily with eight of the twelve English universities that this book is concerned: Birmingham, Bristol, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Nottingham, Reading and Sheffield" (p. 25) and, with respect to Durham, that "its Newcastle college, perhaps, can properly find a place in this survey" (p. 24).[2]

- 1 2 3 Bruce Truscot (1951). Red Brick University (2nd ed.). Pelican. pp. 24–25.

- ↑ "A history of the HE environment". University of St Andrews. Archived from the original on 26 May 2007.

- 1 2 "red-brick". Oxford Living Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- 1 2 "Birmingham University Firsts". Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- 1 2 "About the University of Bristol". Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- ↑ "Origins of the University of Leeds". Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- 1 2 "About the University of Liverpool". Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- 1 2 "University of Manchester: History". Archived from the original on 24 February 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- 1 2 "About the University of Sheffield". Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- ↑ Peers, Edgar Allison (1943). Redbrick University.

- ↑ Russell Group: Home

- ↑ Mackenzie & Allan (1996). Redbrick University Revisited. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-259-8.

- ↑ Harold Silver (1999). "The universities' speaking conscience: “Bruce Truscot” and Redbrick University". Journal of the History of Education Society. 28 (2): 173.

- ↑ Feingold, Mordechai (2006). History of Universities, Vol. XXI/1. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Allison Peers (under the pseudonym 'Bruce Truscot'), Edgar (1943). Redbrick University. Faber & Faber Ltd.

- ↑ "University of Liverpool". Russell Group website. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ "University of Liverpool guide". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ "University of Birmingham Professorial Announcement" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ "Complete University Guide, University of Birmingham". Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ In Churchill's Shadow: Confronting the Past in Modern Britain. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ Egiins, Heather (2010). Access and Equity, Comparative Perspectives (PDF). Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense. p. 12. ISBN 978-94-6091-184-2. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ↑ "Humboldt University Structural Model and History". Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- 1 2 Sanderson, Michael (2002). The History of the University of East Anglia, Norwich. London: Hambledon & London. p. 3. ISBN 1852853360. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ↑ "Facts and figures". University of Sheffield. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ↑ "History of the University". Newcastle University. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ "The University of Reading is 85 years old". 16 March 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ "A brief history of the University". University of Nottingham. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- 1 2 "History of the Victoria University of Manchester". University of Manchester. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Heritage". University of Leeds. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ↑ "History of UMIST". University of Manchester. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ↑ John Morgan (12 November 2015). "How the redbrick universities created British higher education".

Professor Whyte said that Truscot’s term “describes the late 19th, early 20th-century foundations”: including Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, Bristol, Sheffield, Newcastle, as well as Dundee “and the Welsh universities” beyond England.

- ↑ Report of the Committee appointed by the Prime Minister under the Chairmanship of Lord Robbins. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1963. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ↑ "The University's History". University of Reading. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ↑ "Facts and figures about the university". University of Reading. Archived from the original on 1 July 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ "Queen's University Belfast". Study Across The Pond. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

Queen’s is a world-class, red-brick university situated in Belfast, the regional capital of Northern Ireland.

- ↑ Peter Blyth and Arran Cleminson (September 2016). "Teaching Excellence Framework: analysis of highly skilled employmentoutcomes" (PDF). Department for Education. p. 18. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ↑ Harry Mount (24 October 2015). "Corbyn's purge of the Oxbridge set". The Spectator.

Corbyn, perhaps because of his low-grade education, has largely replaced the Oxbridge elite — who ran the Labour party under Ed Miliband — with red-brick alumni. John McDonnell, the shadow chancellor, left school at 17 and was later a mature student at Brunel and Birkbeck universities. Tom Watson, the deputy leader, was at Hull University, as were Rosie Winterton, the shadow chief whip, and Jon Trickett, shadow minister for the cabinet office. Hilary Benn, shadow foreign secretary, was at Sussex, as were Owen Smith, shadow secretary for work and pensions, and Lord Bassam, the Labour chief whip in the Lords. Michael Dugher, shadow culture secretary, was at Nottingham University. And Gloria De Piero, shadow minister for young people, attended the University of Westminster.

Further reading

- Whyte, William. Redbrick: A Social and Architectural History of Britain's Civic Universities (2015).