Watermelon

| Watermelon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Watermelon | |

| |

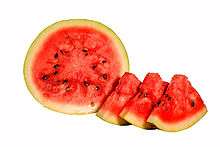

| Watermelon cross section | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Cucurbitales |

| Family: | Cucurbitaceae |

| Genus: | Citrullus |

| Species: | C. lanatus |

| Variety: | lanatus |

| Trinomial name | |

| Citrullus lanatus var. lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai | |

| | |

| Watermelon output in 2005 | |

Watermelon Citrullus lanatus var. lanatus is a scrambling and trailing vine in the flowering plant family Cucurbitaceae. The species originated in southern Africa, and there is evidence of its cultivation in Ancient Egypt. It is grown in tropical and sub-tropical areas worldwide for its large edible fruit, also known as a watermelon, which is a special kind of berry with a hard rind and no internal division, botanically called a pepo. The sweet, juicy flesh is usually deep red to pink, with many black seeds. The fruit can be eaten raw or pickled and the rind is edible after cooking.

Considerable breeding effort has been put into disease-resistant varieties and into developing a "seedless" strain with only digestible white seeds. Many cultivars are available that produce mature fruit within 100 days of planting the crop.

Description

The watermelon is a large annual plant with long, weak, trailing or climbing stems which are five-angled (five-sided) and up to 3 m (10 ft) long. Young growth is densely woolly with yellowish-brown hairs which disappear as the plant ages. The leaves are large, coarse, hairy pinnately-lobed and alternate; they get stiff and rough when old. The plant has branching tendrils. The white to yellow flowers grow singly in the leaf axils and the corolla is white or yellow inside and greenish-yellow on the outside. The flowers are unisexual, with male and female flowers occurring on the same plant (monoecious). The male flowers predominate at the beginning of the season; the female flowers, which develop later, have inferior ovaries. The styles are united into a single column. The large fruit is a kind of modified berry called a pepo with a thick rind (exocarp) and fleshy center (mesocarp and endocarp).[1] Wild plants have fruits up to 20 cm (8 in) in diameter, while cultivated varieties may exceed 60 cm (24 in). The rind of the fruit is mid- to dark green and usually mottled or striped, and the flesh, containing numerous pips spread throughout the inside, can be red or pink (most commonly), orange, yellow, green or white.[2][3]

History

The watermelon is a flowering plant thought to have originated in southern Africa, where it is found growing wild. It reaches maximum genetic diversity there, with sweet, bland and bitter forms. In the 19th century, Alphonse de Candolle[4] considered the watermelon to be indigenous to tropical Africa.[5] Citrullus colocynthis is often considered to be a wild ancestor of the watermelon and is now found native in north and west Africa. However, it has been suggested on the basis of chloroplast DNA investigations that the cultivated and wild watermelon diverged independently from a common ancestor, possibly C. ecirrhosus from Namibia.[6]

Evidence of its cultivation in the Nile Valley has been found from the second millennium BC onward. Watermelon seeds have been found at Twelfth Dynasty sites and in the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun.[7]

In the 7th century, watermelons were being cultivated in India, and by the 10th century had reached China, which is today the world's single largest watermelon producer. The Moors introduced the fruit into Spain and there is evidence of it being cultivated in Córdoba in 961 and also in Seville in 1158. It spread northwards through southern Europe, perhaps limited in its advance by summer temperatures being insufficient for good yields. The fruit had begun appearing in European herbals by 1600, and was widely planted in Europe in the 17th century as a minor garden crop.[2]

European colonists and slaves from Africa introduced the watermelon to the New World. Spanish settlers were growing it in Florida in 1576, and it was being grown in Massachusetts by 1629, and by 1650 was being cultivated in Peru, Brazil and Panama, as well as in many British and Dutch colonies. Around the same time, Native Americans were cultivating the crop in the Mississippi valley and Florida. Watermelons were rapidly accepted in Hawaii and other Pacific islands when they were introduced there by explorers such as Captain James Cook.[2]

Seedless watermelons were initially developed in 1939 by Japanese scientists who were able to create seedless triploid hybrids which remained rare initially because they did not have sufficient disease resistance.[8] Seedless watermelons became more popular in the 21st century, rising to nearly 85% of total watermelon sales in the United States in 2014.[9]

Cultivation

Watermelons are tropical or subtropical plants and need temperatures higher than about 25 °C (77 °F) to thrive. On a garden scale, seeds are usually sown in pots under cover and transplanted into well-drained sandy loam with a pH between 5.5 and 7, and medium levels of nitrogen.

Major pests of the watermelon include aphids, fruit flies and root-knot nematodes. In conditions of high humidity, the plants are prone to plant diseases such as powdery mildew and mosaic virus.[10] Some varieties often grown in Japan and other parts of the Far East are susceptible to fusarium wilt. Grafting such varieties onto disease-resistant rootstocks offers protection.[2]

The US Department of Agriculture recommends using at least one beehive per acre (4,000 m2 per hive) for pollination of conventional, seeded varieties for commercial plantings. Seedless hybrids have sterile pollen. This requires planting pollinizer rows of varieties with viable pollen. Since the supply of viable pollen is reduced and pollination is much more critical in producing the seedless variety, the recommended number of hives per acre (pollinator density) increases to three hives per acre (1,300 m2 per hive). Watermelons have a longer growing period than other melons, and can often take 85 days or more from the time of transplanting for the fruit to mature.[11]

Farmers of the Zentsuji region of Japan found a way to grow cubic watermelons by growing the fruits in metal and glass boxes and making them assume the shape of the receptacle.[12] The cubic shape was originally designed to make the melons easier to stack and store, but cubic watermelons may be triple the price of normal ones, so appeal mainly to wealthy urban consumers.[12] Pyramid-shaped watermelons have also been developed and any polyhedral shape may potentially be used.[13]

Varieties

The more than 1200[14] cultivars of watermelon range in weight from less than 1 kg to more than 90 kilograms (200 lb); the flesh can be red, pink, orange, yellow or white.[11]

- The 'Carolina Cross' produced the current world record for heaviest watermelon, weighing 159 kilograms (351 pounds).[15] It has green skin, red flesh and commonly produces fruit between 29 and 68 kilograms (65 and 150 lb). It takes about 90 days from planting to harvest.[16]

- The 'Golden Midget' has a golden rind and pink flesh when ripe, and takes 70 days from planting to harvest.[17]

- The 'Orangeglo' has a very sweet orange flesh, and is a large, oblong fruit weighing 9–14 kg (20–31 lb). It has a light green rind with jagged dark green stripes. It takes about 90–100 days from planting to harvest.[18]

- The 'Moon and Stars' variety was created in 1926.[19] The rind is purple/black and has many small yellow circles (stars) and one or two large yellow circles (moon). The melon weighs 9–23 kg (20–51 lb).[20] The flesh is pink or red and has brown seeds. The foliage is also spotted. The time from planting to harvest is about 90 days.[21]

- The 'Cream of Saskatchewan' has small, round fruits about 25 cm (9.8 in) in diameter. It has a thin, light and dark green striped rind, and sweet white flesh with black seeds. It can grow well in cool climates. It was originally brought to Saskatchewan, Canada, by Russian immigrants. The melon takes 80–85 days from planting to harvest.[22]

- The 'Melitopolski' has small, round fruits roughly 28–30 cm (11–12 in) in diameter. It is an early ripening variety that originated from the Astrakhan region of Russia, an area known for cultivation of watermelons. The Melitopolski watermelons are seen piled high by vendors in Moscow in the summer. This variety takes around 95 days from planting to harvest.[23]

- The 'Densuke' watermelon has round fruit up to 11 kg (24 lb). The rind is black with no stripes or spots. It is grown only on the island of Hokkaido, Japan, where up to 10,000 watermelons are produced every year. In June 2008, one of the first harvested watermelons was sold at an auction for 650,000 yen (US$6,300), making it the most expensive watermelon ever sold. The average selling price is generally around 25,000 yen ($250).[24]

- Many cultivars are no longer grown commercially because of their thick rind, but seeds may be available among home gardeners and specialty seed companies. This thick rind is desirable for making watermelon pickles, and some old cultivars favoured for this purpose include 'Tom Watson', 'Georgia Rattlesnake', and 'Black Diamond'.[25]

Variety improvement

Charles Fredric Andrus, a horticulturist at the USDA Vegetable Breeding Laboratory in Charleston, South Carolina, set out to produce a disease-resistant and wilt-resistant watermelon. The result, in 1954, was "that gray melon from Charleston". Its oblong shape and hard rind made it easy to stack and ship. Its adaptability meant it could be grown over a wide geographical area. It produced high yields and was resistant to the most serious watermelon diseases: anthracnose and fusarium wilt.[26]

Others were also working on disease-resistant varieties; J. M. Crall at the University of Florida produced "Jubilee" in 1963 and C. V. Hall of Kansas State University produced "Crimson sweet" the following year. These are no longer grown to any great extent, but their lineage has been further developed into hybrid varieties with higher yields, better flesh quality and attractive appearance.[2] Another objective of plant breeders has been the elimination of the seeds which occur scattered throughout the flesh. This has been achieved through the use of triploid varieties, but these are sterile, and the cost of producing the seed by crossing a tetraploid parent with a normal diploid parent is high.[2]

Today, farmers in approximately 44 states in the United States grow watermelon commercially. Georgia, Florida, Texas, California and Arizona are the United States' largest watermelon producers. This now-common fruit is often large enough that groceries often sell half or quarter melons. Some smaller, spherical varieties of watermelon—both red- and yellow-fleshed—are sometimes called "icebox melons".[27] The largest recorded fruit was grown in Tennessee in 2013 and weighed 159 kilograms (351 pounds).[15]

| Major watermelon producers, 2014 (millions of tonnes)[28] | |

|---|---|

Production

In 2014, global production of watermelons was 111 million tonnes, with China alone accounting for 67% of the total.[28] Secondary producers each with less than 4% of world production included Turkey, Iran, Brazil and Egypt.[28]

Food and beverage

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 127 kJ (30 kcal) |

|

7.55 g | |

| Sugars | 6.2 g |

| Dietary fiber | 0.4 g |

|

0.15 g | |

|

0.61 g | |

| Vitamins | |

| Vitamin A equiv. |

(4%) 28 μg (3%) 303 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) |

(3%) 0.033 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

(2%) 0.021 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

(1%) 0.178 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) |

(4%) 0.221 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

(3%) 0.045 mg |

| Choline |

(1%) 4.1 mg |

| Vitamin C |

(10%) 8.1 mg |

| Minerals | |

| Calcium |

(1%) 7 mg |

| Iron |

(2%) 0.24 mg |

| Magnesium |

(3%) 10 mg |

| Manganese |

(2%) 0.038 mg |

| Phosphorus |

(2%) 11 mg |

| Potassium |

(2%) 112 mg |

| Sodium |

(0%) 1 mg |

| Zinc |

(1%) 0.1 mg |

| Other constituents | |

| Water | 91.45 g |

| Lycopene | 4532 µg |

|

| |

| |

|

Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Watermelons are a sweet, popular fruit of summer, usually consumed fresh in slices, diced in mixed fruit salads, or as juice.[29][30] Watermelon juice can be blended with other fruit juices or made into wine.[31]

The seeds have a nutty flavor and can be dried and roasted, or ground into flour.[3] In China, the seeds are eaten at Chinese New Year celebrations.[32] In Vietnamese culture, watermelon seeds are consumed during the Vietnamese New Year's holiday, Tết, as a snack.[33]

Watermelon rinds may be eaten, but most people avoid eating them due to their unappealing flavor. They are used for making pickles,[25] sometimes eaten as a vegetable, stir-fried or stewed.[3][34]

The Oklahoma State Senate passed a bill in 2007 declaring watermelon as the official state vegetable, with some controversy about whether it is a vegetable or a fruit.[35]

Citrullis lanatus, variety caffer, grows wild in the Kalahari Desert, where it is known as tsamma.[3] The fruits are used by the San people and wild animals for both water and nourishment, allowing survival on a diet of tsamma for six weeks.[3]

Nutrients

Watermelon fruit is 91% water, contains 6% sugars, and is low in fat (table).[36]

In a 100 gram serving, watermelon fruit supplies 30 calories and low amounts of essential nutrients (table). Only vitamin C is present in appreciable content at 10% of the Daily Value (table). Watermelon pulp contains carotenoids, including lycopene.[37]

The amino acid citrulline is produced in watermelon rind.[38][39]

Gallery

Watermelon cubes

Watermelon cubes Watermelons with black rind, India

Watermelons with black rind, India Watermelon flowers

Watermelon flowers Watermelon leaf

Watermelon leaf- Flower stems of male and female watermelon blossoms, showing ovary on the female

Watermelon plant close-up

Watermelon plant close-up Watermelon with yellow flesh

Watermelon with yellow flesh 'Moon and stars' watermelon cultivar

'Moon and stars' watermelon cultivar Watermelon and other fruit in Boris Kustodiev's Merchant's Wife

Watermelon and other fruit in Boris Kustodiev's Merchant's Wife

References

- ↑ "A Systematic Treatment of Fruit Types". Worldbotanical.com. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Maynard, David; Maynard, Donald N. (2012). "6: Cucumbers, melons and watermelons". In Kiple, Kenneth F.; Ornelas, Kriemhild Coneè. The Cambridge World History of Food, Part 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40215-6. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521402156.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai". South Africa National Biodiversity Institute. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ Candolle, Origin of Cultivated Plants (1882) pp 262ff, s.v. "Water-melon".

- ↑ Wehner, Todd C. Watermelon Crop Information. North Carolina State University

- ↑ Dane, Fenny; Liu, Jiarong (2006). "Diversity and origin of cultivated and citron type watermelon (Citrullus lanatus)". Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 54 (6): 1255. doi:10.1007/s10722-006-9107-3.

- ↑ Zohary, Daniel and Hopf, Maria (2000) Domestication of Plants in the Old World, third edition, Oxford University Press, p. 193, ISBN 0-19-850357-1.

- ↑ "Production of Seedless Watermelons". US Department of Agriculture. 15 June 1971. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ↑ Naeve, Linda (December 2015). "Watermelon". agmrc.org. Agricultural Marketing Resource Center. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ↑ Brickell, Christopher (ed) (1992). The Royal Horticultural Society Encyclopedia of Gardening (Print). London: Dorling Kindersley. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-86318-979-1.

- 1 2 "Watermelon Variety Descriptions". Washington State University. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Square fruit stuns Japanese shoppers". BBC News. 15 June 2001.

- ↑ "Square watermelons Japan. English version". YouTube. 6 November 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ↑ "Vegetable Research & Extension Center – Icebox Watermelons". Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- 1 2 "Heaviest watermelon". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ↑ "Watermelon growing contest". Georgia 4H. The University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. 2005. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ "Golden Midget Watermelon". Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ "Orangeglo Watermelon". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- ↑ "Moon and Stars Watermelon Heirloom". rareseeds.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ↑ Evans, Lynette (15 July 2005). "Moon & Stars watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) — Seed-spittin' melons makin' a comeback". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2007.

- ↑ "Moon and Stars Watermelon". Archived from the original on 2 June 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- ↑ "Watermelon, Cream Saskatchewan". seedsavers.org. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009.

- ↑ "Melitopolski Watermelon". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- ↑ Hosaka, Tomoko A. (6 June 2008). "Black Japanese watermelon sold at record price". The Associated Pres. Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- 1 2 Todd C. Wehner (2008). "12. Watermelon". In Jaime Prohens and Fernando Nuez. Handbook of plant breeding. Volume 1, Vegetables. I, Asteraceae, Brassicaceae, Chenopodicaceae, and Cucurbitaceae. Springer. pp. 381–418. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-30443-4_12.

- ↑ "Watermelon developer dies at 101". Post and Courier, 16 July 2007

- ↑ "Good reasons for icebox melons". The Free Library. Sunset. 1 May 1985. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Watermelon production in 2014; Crops/Regions (World list)/Production quantity (from pick lists)". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Statistics Division (FAOSTAT). 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ↑ "Watermelon". g Marketing Resource Center, US Department of Agriculture, Iowa State University. 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ "Top 10 ways to enjoy watermelon". Produce for Better Health Foundation, Centers for Disease Control, US National Institutes of Health. 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ Ogodo, A. C.; Ugbogu, O. C.; Ugbogu, A. E.; Ezeonu, C. S. (2015). "Production of mixed fruit (pawpaw, banana and watermelon) wine using Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolated from palm wine". SpringerPlus. 4: 683. PMC 4639538

. PMID 26576326. doi:10.1186/s40064-015-1475-8.

. PMID 26576326. doi:10.1186/s40064-015-1475-8. - ↑ Shiu-ying Hu (2005). Food Plants of China. Chinese University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-962-996-229-6.

- ↑ The Asian Texans By Marilyn Dell Brady, Texas A&M University Press

- ↑ Bryant Terry (2009). Vegan Soul Kitchen: Fresh, Healthy, and Creative African-American Cuisine. Da Capo Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-7867-4503-6.

- ↑ "Oklahoma Declares Watermelon Its State Vegetable". CBS4denver. 18 April 2007. Archived from the original on 2 March 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ↑ "Watermelon, raw". Nutritional data. Self. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ Perkins-Veazie P, Collins JK, Davis AR, Roberts W (2006). "Carotenoid content of 50 watermelon cultivars". J Agric Food Chem. 54 (7): 2593–7. PMID 16569049. doi:10.1021/jf052066p.

- ↑ Rimando AM, Perkins-Veazie PM (2005). "Determination of citrulline in watermelon rind". J Chromatogr A. 1078 (1–2): 196–200. PMID 16007998. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2005.05.009.

- ↑ The Associated Press (3 July 2008). "CBC News – Health – Watermelon the real passion fruit?". CBC. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Citrullus vulgaris |

Media related to Citrullus lanatus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Citrullus lanatus at Wikimedia Commons