Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal

Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Exterior view of the Cincinnati Museum Center | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location |

1301 Western Avenue Cincinnati, OH | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owned by | City of Cincinnati | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line(s) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platforms | 1 side platform | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tracks | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Connections | SORTA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Construction | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Disabled access | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station code | CIN | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1933 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rebuilt | 1980 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traffic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Passengers (2013) |

15,213[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cincinnati Union Terminal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | 1301 Western Ave., Cincinnati, Ohio | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 39°6′36″N 84°32′16″W / 39.11000°N 84.53778°WCoordinates: 39°6′36″N 84°32′16″W / 39.11000°N 84.53778°W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Built | 1933 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architect | Fellheimer & Wagner | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architectural style | Art Deco | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NRHP Reference # | 72001018[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Added to NRHP | October 31, 1972 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal, originally Cincinnati Union Terminal, is a passenger railroad station in the Queensgate neighborhood of Cincinnati, Ohio, United States. After the decline of railroad travel, most of the building was converted to other uses, and now houses museums, theaters, and a library, as well as special travelling exhibitions.

Background

Cincinnati was a major center of railroad traffic in the late 19th and early 20th century, especially as an interchange point between railroads serving the Northeastern and Midwestern states with railroads serving the South. However, intercity passenger traffic was split among no fewer than five stations in Downtown Cincinnati, requiring the many travelers who changed between railroads to navigate local transit themselves.[3] The Louisville and Nashville Railroad, which operated through sleepers with other railroads, was forced to split its operations between two stations.[4] Proposals to construct a union station began as early as the 1890s, and a committee of railroad executives formed in 1912 to begin formal studies on the subject, but a final agreement between all seven railroads that served Cincinnati and the city itself would not come until 1928, after intense lobbying and negotiations, led by Philip Carey Company president George Crabbs.[3] The seven railroads: the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad; the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad; the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railway; the Louisville and Nashville Railroad; the Norfolk and Western Railway; the Pennsylvania Railroad; and the Southern Railway selected a site for their new station in the West End, near the Mill Creek.

Architecture and design

The principal architects of the massive building were Alfred T. Fellheimer and Steward Wagner,[5] with architects Paul Philippe Cret and Roland Wank brought in as design consultants; Cret is often credited as the building's architect, as he was responsible for the building's signature Art Deco style. The Rotunda features the largest semi-dome in the western hemisphere, measuring 180 feet (55 m) wide and 106 feet (32 m) high.[6]

The artists and artwork

Maxfield Keck

Maxfield Keck was commissioned to use bas-relief carvings to design artwork for the front of the building, which are clearly visible when viewing the building from the exterior, and represent Transportation (South Tower) and Commerce (North tower).[7]

Winold Reiss

German American artist Winold Reiss was commissioned to design and create two 22 foot (6.7 m) high by 110 foot (33.5 m) long color mosaic murals depicting the history of Cincinnati for the rotunda, two murals for the baggage lobby, two murals for the departing and arriving train boards, 16 smaller murals for the train concourse representing local industries and the large world map mural located at the rear of the concourse. Reiss spent roughly two years in the design and creation of the murals. The 16 industry murals chosen for the railroad concourse include:

- Piano making (Baldwin Piano Company)

- Radio broadcasting (Crosley Broadcasting Corporation)

- Roof manufacture (Philip Carey Co.)

- Tanning (American Oak Leather Co.)

- Airplane and parts manufacture (Aeronca Aircraft Company)

- Ink making (Ault & Weiborg Corp.)

- Laundry-machinery manufacture (American Laundry Machine)

- Meat packing (Kahn's Meat Packing)

- Drug and chemical processing (William S. Merrill Co.)

- Printing and publishing (U.S. Playing Card Co. and Champion Paper Company)

- Foundry products operations (Cincinnati Milling Machine)

- Sheet steel making (American Rolling Mills and Newport Rolling Mill)

- Soap making (The Procter & Gamble Co.)

- Machine tools manufacture (Cincinnati Milling Machine)

- Pottery manufacture (two Rookwood Pottery murals, potter and kiln master)

Fourteen of the murals located in the train concourse were removed in 1972 when the concourse building was demolished, and placed on display at the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport at a cost of $1 million.[8] The two Rookwood Pottery murals remained at Union Terminal and have been relocated to the Machine Tool Gallery in the Cincinnati History Museum, while the arriving and departing trains murals were moved in front of the entrance to the Cincinnati Historical Library.[9] With Terminal 1 and Terminal 2 being demolished, nine of the murals are being relocated to the Duke Energy Convention Center.[10] Five murals remain in the main terminal at the airport.

Pierre Bourdelle

Pierre Bourdelle, son of renowned French sculptor Antoine Bourdelle, also created commissioned artwork for the terminal, including a Jungle-themed mural for the Women's Lounge, men's lounge, baggage checking area, meeting spaces, and the executive offices. All of his artwork, which was all recently restored is available for public view by free tours.[7]

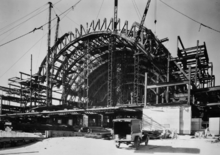

Construction

The Union Terminal Company was created to build the terminal, railroad lines in and out, and other related transportation improvements. Construction in 1928 with the regrading of the east flood plain of the Mill Creek to a point nearly level with the surrounding city, a massive effort that required 5.5 million cubic yards of landfill.[4] Other improvements included the construction of grade separated viaducts over the Mill Creek and the railroad approaches to Union Terminal. The new viaducts the Union Terminal Company created to cross the Mill Creek valley ranged from the well built, like the Western Hills Viaduct,[3] to the more hastily constructed and shabby, like the Waldvogel Viaduct.[11] Construction on the terminal building itself began in 1931, with Cincinnati mayor Russell Wilson laying the mortar for the cornerstone. Construction was finished ahead of schedule,[3] although the terminal welcomed its first trains even earlier on March 19, 1933 when it was forced into emergency operation due to flooding of the Ohio River. The official opening of the station was on March 31, 1933. The total cost of the project was $41.5 million.

Operation

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

During its heyday as a passenger rail facility, Union Terminal had a capacity of 216 trains per day, 108 in and 108 out. Three concentric lanes of traffic were included in the design of the building, underneath the main rotunda of the building: one for taxis, one for buses, and one (although never used) for streetcars. However, the time period in which the terminal was built was one of decline for train travel. By 1939, local newspapers were already describing the station as a white elephant.[3] While it had a brief revival in the 1940s, because of World War II, it declined in use through the 1950s and the 1960s.

In 1971, after the creation of Amtrak, train service at Union Terminal was reduced to just two trains a day, the George Washington and the James Whitcomb Riley. Amtrak abandoned Union Terminal the next year, opening a smaller station elsewhere in Cincinnati on October 29, 1972.[3]

Named trains of Cincinnati's Union Terminal

| Name | Operators | Year begun | Year discontinued |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardinal | Amtrak | 1977 | |

| Carolina Special | Southern Railway | 1911 | 1968 |

| Cavalier | N & W | ||

| Cincinnati Limited | PRR, PC | 1971 | |

| Cincinnati Mercury | NYC | ||

| Cincinnatian | B & O | 1947 | 1971 |

| Fast Flying Virginian | C & O | 1889 | 1968 |

| Flamingo | L & N | 1925 | 1968 |

| George Washington | C & O, Amtrak | 1974 | |

| Humming Bird | L & N | 1947 | 1968 |

| James Whitcomb Riley | NYC, PC, Amtrak | 1977 | |

| Metropolitan Special | B & O | 1971 | |

| National Limited | B & O | 1916 | 1971 |

| Northern Arrow | PRR | 1961 | |

| Ohio State Limited | NYC, PC | 1924 | 1967 |

| Pan-American | L & N | 1921 | 1971 |

| Pocahontas | N & W | 1926 | 1971 |

| Ponce de Leon | SOU | 1924 | 1968 |

| Powhatan Arrow | N & W | 1946 | 1969 |

| Royal Palm | SOU | 1949 | 1970 |

| South Wind | L & N | 1940 | 1971 |

| Xplorer | NYC | 1956 | 1960 |

Science Center

The Cincinnati Science Center operated in Union Terminal from 1968 to 1970 on the south side of the main concourse. The Science Center closed after two years due to financial difficulties.

Later years

Abandonment and reduction

After Amtrak abandoned the station, Southern Railway purchased some of the land to use for its own expanded freight operations in its Gest Street yard. The Southern planned on removing the 450-foot (140 m) long passenger train concourse to allow additional height for its piggyback operations. On May 15, 1973 the Cincinnati City Council's Urban Development and Planning Committee voted 3–1 in favor of designating Union Terminal for preservation as a historic landmark, preventing Southern Railway from destroying the entire building. In 1974, the Southern Railway did tear down most of the train concourse. Before the concourse building was torn down, the fourteen mosaic murals depicting important Cincinnati industries were removed by Besl Transfer Company from the concourse and installed at the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport. The only mural which was not preserved was the world map, which was destroyed.

Several plans were floated for reuse of the building in the 1970s, including a plan to locate a Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Authority transit hub and the School for Creative and Performing Arts in the building, but these never materialized.[3]

Shopping mall

In 1978, Columbus, Ohio real estate development group the Joseph Skilken Organization converted the terminal into a shopping mall known as the "Land of OZ". This was projected to be a family entertainment and shopping complex including a shopping area, roller skating rink, bowling alleys, and restaurants. Skilken invested upwards of $20 million in renovations preparing the terminal in the hope that this would revitalize the complex and help keep people in downtown Cincinnati.

These plans were put into action and on August 4, 1980, after 23 months of conversion construction, the mall had its Grand Opening, with 40 tenants. The complex drew on average 7,900 visitors per day and it would see a high of 54 shops or vendors. The recession of the early 1980s caused the project to fall on hard times. In 1981 the first tenant moved out and by 1982 the number of tenants had fallen to 21. Also in August 1982, the Cincinnati Museum of Health, Science and Industry opened in the terminal. The OZ project officially closed in 1984. However, Loehmann's, a clothing store located in the rotunda remained open until 1985. The passenger drop off ramps that ran under the rotunda were used for a weekend flea market for several years.

Museum Center and reuse as train station

The terminal lay empty for the next decade or so. In May 1986 the voters of Hamilton County passed a bond levy to save the terminal from destruction and to transform it into the Cincinnati Museum Center. Former Cincinnati mayor Jerry Springer was one of the major proponents of saving the building and transforming it into a museum. It was opened in 1990 and now provides a home to six organizations:

- Cincinnati History Museum

- Museum of Natural History & Science

- Robert D. Lindner Family Omnimax Theater, a five story domed movie house[12]

- Cincinnati Historical Society Library

- Duke Energy Children's Museum

- The Cincinnati Railroad Club

The renovations also allowed Amtrak to restore service to Union Terminal via the thrice-weekly Cardinal on July 29, 1991. Of the seven Ohio stations served by Amtrak, Cincinnati was the third busiest in FY2010, boarding or disembarking an average of approximately 40 passengers daily.

The Cincinnati Railroad Club occupies "Tower A" above the station, offers public access to the space, and serves as a museum for the former rail yard and station's innovative interlocking system of remote-controlled track switches.

In June 2014 the National Trust for Historic Preservation named Union Terminal as one of the 11 most endangered historic places in the country due to deterioration.[13]

From late 2016 until 2018, most of the museum will be shut down in order to complete much needed structural renovations throughout the entire building, in addition to restoring a number of rooms original to the building. Due to the flat roofs on large portions of the building, water damage has caused rotting to the roofs and walls. The renovation is necessary in order to save the building from collapsing. During the closure, items located in the museum will be stored in The Geier Center, which is the museum's storage facility, and in various traveling exhibits across the country.

In fiction

Outside of Cincinnati, Union Terminal is mostly known for its appearances on television. In the 1970s animated series Super Friends, the imposing headquarters of the Justice League, the Hall of Justice, was modeled after Union Terminal. The show's producer, Hanna-Barbera, was at the time owned by Cincinnati-based Taft Broadcasting. In 2016, a four-night crossover event, "Invasion!", which linked The CW network's four DC Comics-related live-action TV series - Supergirl, The Flash, Arrow, and DC's Legends of Tomorrow - featured digitally-modified footage of Union Terminal as a hangar owned by Barry Allen/The Flash, meant to evoke the Hall of Justice from Super Friends.[14]

Union Terminal was also featured in the 1996 comic book series Terminal City.[15][16]

Sources

- Darbee, Jeffrey T. (2003). "A Tale of Three Cities: The Union Stations of Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati", paper delivered in 2003 at the Railroad Symposium on Union Stations at the Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, Indiana.

- Mecklenborg, Jake (2005). Cincinnati-Transit.net.

- Spurlock, William (2005). The Railroad Architecture of Alfred T. Fellheimer.

- The Railroad and the City, A Technological and Urbanistic History of Cincinnati, Written by Carl W. Condit. 1977, Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0-8142-0265-9

- Works Progress Administration(ed. Harry Graff)(1943). WPA Guide to Cincinnati: Cincinnati, a guide to the Queen City and its neighbors. Cincinnati: The Cincinnati Historical Society. ISBN 0-911497-04-8.

References

- ↑ "Amtrak Fact Sheet, FY2013, State of Ohio" (PDF). Amtrak. November 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ↑ National Park Service (2008-04-15). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 writers, Linda C. Rose, Patrick Rose, Gibson Yungblut ; editors, Linda C. Rose ...; et al. (October 1999). Cincinnati Union Terminal: The Design and Construction of an Art Deco Masterpiece. Cincinnati, Ohio: Cincinnati Railroad Club, Inc. ISBN 0-9676125-0-0.

- 1 2 "Cincinnati's New Union Terminal Now in Service". Railway Age. 94 (16): 575–590. 1933.

- ↑ Rolfes, Steven (October 29, 2012). Cincinnati Landmarks. Arcadia Publishing. p. 39. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ↑ Cincinnati Union Terminal Architectural Information Sheet Archived June 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.. Cincinnati Museum Center. Retrieved on February 8, 2010.

- 1 2 "Gateway to the City, Cincinnati Union Terminal at Seventy-Five". Cincinnati Historical Society. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ↑ Tate, Skip (August 1994). "Airport Trivia". Cincinnati. CM Media. p. 70. ISSN 0746-8210. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ↑ http://local.cincinnati.com/community/pages/murals/index.html

- ↑ http://www.wcpo.com/news/local-news/hamilton-county/cincinnati/downtown/union-terminal-murals-to-be-mounted-outside-convention-center

- ↑ Waldvogel Viaduct

- ↑ Smith, Steve; et al. (2007). "Movie Theaters". Cincinnati USA City Guide. Cincinnati Magazine. p. 20. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ↑ Union Terminal at the Wayback Machine (archived July 1, 2014)

- ↑ Prudom, Laura (November 29, 2016). "Hey, comic book fans, did you catch this Super 'Flash' easter egg?". Mashable. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- ↑ Shebar, Alex (March 25, 2009). "Meanwhile, at the Hall of Justice ...". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Gannett Company. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ↑ Dobush, Grace (October 30, 2014). "The Real-Life Inspiration for the Super Friends' Hall of Justice Is in Danger". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal. |

- Official website

- Cincinnati Union Terminal Photos – interior and exterior

- 360˚ interactive panoramas of Union Terminal Exterior and rotunda

- Amtrak – Stations – Cincinnati, OH

- Cincinnati, OH (CIN) (Amtrak's Great American Stations)