Christopher Nolan

| Christopher Nolan | |

|---|---|

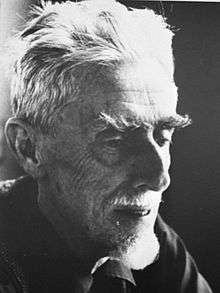

.jpg) Nolan at the 2013 premiere of Man of Steel in London | |

| Born |

Christopher Edward Nolan 30 July 1970 Westminster, London, England, United Kingdom |

| Alma mater | University College London |

| Occupation | Filmmaker |

| Years active | 1989–present |

| Spouse(s) | Emma Thomas (m. 1997) |

| Children | 4 |

| Relatives |

Jonathan Nolan (brother) Lisa Joy (sister-in-law) John Nolan (uncle) Kim Hartman (aunt) |

Christopher Edward Nolan[1] (/ˈnoʊlən/; born 30 July 1970)[2] is an English-American film director, producer, and screenwriter. He is one of the highest-grossing directors in history, and among the most successful and acclaimed filmmakers of the 21st century.

Having made his directorial debut with Following (1998), Nolan gained considerable attention for his second feature, Memento (2000), for which he received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. The acclaim garnered by his independent films gave Nolan the opportunity to make the big-budget thriller Insomnia (2002) and the mystery drama The Prestige (2006). He found further popular and critical success with The Dark Knight Trilogy (2005–2012); Inception (2010), for which he received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Picture and a second Original Screenplay nomination; Interstellar (2014) and Dunkirk (2017). His ten films have grossed over US$4.5 billion worldwide and garnered a total of 26 Oscar nominations and seven wins. Nolan has co-written several of his films with his younger brother, Jonathan, and runs the production company Syncopy Inc. with his wife, Emma Thomas.

Nolan's films are rooted in philosophical, sociological and ethical concepts, exploring human morality, causality, the construction of time, and the malleable nature of memory and personal identity. His body of work is permeated by materialistic perspectives, labyrinthine plots, nonlinear storytelling, practical special effects, and analogous relationships between visual language and narrative elements.

Biography

Early life and career beginnings: 1970–1997

Nolan was born in London. His British father, Brendan James Nolan, was an advertising executive, and his American mother, Christina (née Jensen), worked as a flight attendant and an English teacher.[4][5][6][7] His childhood was split between London and Evanston, Illinois, and he has both British and US citizenship.[8][9][10][11] He has an older brother, Matthew Francis Nolan, a convicted criminal,[12] and a younger brother, Jonathan.[13] He began making films at age seven, borrowing his father's Super 8 camera and shooting short films with his action figures.[14][15] Growing up, Nolan was particularly influenced by Star Wars (1977), and around the age of eight he made a stop motion animation homage called Space Wars. His uncle who worked at NASA, building guidance systems for the Apollo rockets, sent him some launch footage: "I re-filmed them off the screen and cut them in, thinking no-one would notice," Nolan later remarked.[4][16][17] From the age of 11, he aspired to be a professional filmmaker.[13]

When Nolan's family relocated to Chicago during his formative years, he started making films with Adrien and Roko Belic. He has continued his collaboration with the brothers, receiving a credit for his editorial assistance on their Oscar-nominated documentary Genghis Blues (1999).[18] Nolan also worked alongside Roko (and future Pulitzer Prize winner Jeffrey Gettleman) on documenting a safari across four African countries, organized by the late photojournalist Dan Eldon in the early 1990s.[19][20] Nolan was educated at Haileybury and Imperial Service College, an independent school in Hertford Heath, Hertfordshire, and later read English literature at University College London (UCL). He chose UCL specifically for its filmmaking facilities, which comprised a Steenbeck editing suite and 16 mm film cameras.[21] Nolan was president of the Union's Film Society,[21] and with Emma Thomas (his girlfriend and future wife) he screened 35 mm feature films during the school year and used the money earned to produce 16 mm films over the summers.[22] During his college years, Nolan made two short films. The first was the surreal 8 mm Tarantella (1989), which was shown on Image Union (an independent film and video showcase on the Public Broadcasting Service).[23] The second was Larceny (1995), filmed over a weekend in black and white with a limited cast, crew, and equipment.[24] Funded by Nolan and shot with the society's equipment, it appeared at the Cambridge Film Festival in 1996 and is considered one of UCL's best shorts.[25]

After graduation, Nolan worked as a script reader, camera operator, and director of corporate videos and industrial films.[21][7][26] He also made a third short, Doodlebug (1997), about a man chasing an insect around a flat with a shoe, only to discover when killing it that it is a miniature of himself.[27] During this period of his career, Nolan had little or no success getting his projects off the ground; he later recalled the "stack of rejection letters" that greeted his early forays into making films, adding "there's a very limited pool of finance in the UK. To be honest, it's a very clubby kind of place ... Never had any support whatsoever from the British film industry."[28]

Breakthrough: 1998–2002

In 1998 Nolan directed his first feature, which he personally funded and filmed with friends.[29] Following depicts an unemployed young writer (Jeremy Theobald) who trails strangers through London, hoping they will provide material for his first novel, but is drawn into a criminal underworld when he fails to keep his distance. The film was inspired by Nolan's experience of living in London and having his flat burgled: "There is an interesting connection between a stranger going through your possessions and the concept of following people at random through a crowd – both take you beyond the boundaries of ordinary social relations".[30] Following was made on a modest budget of £3,000, and was shot on weekends over the course of a year.[31] To conserve film stock, each scene in the film was rehearsed extensively to ensure that the first or second take could be used in the final edit.[32][33] Co-produced with Emma Thomas and Jeremy Theobald, Nolan wrote, photographed and edited the film himself.[32] Following won several awards during its festival run[34][35] and was well received by critics; The New Yorker wrote that it "echoed Hitchcock classics", but was "leaner and meaner".[14] Janet Maslin of The New York Times was impressed with its "spare look" and agile hand-held camerawork, "As a result, the actors convincingly carry off the before, during and after modes that the film eventually, and artfully, weaves together."[36] On 11 December 2012, it was released on DVD and Blu-ray as part of the Criterion Collection.[37]

—Nolan (in 2012) on the jump from his first film to his second.[29]

As a result of Following's success, Nolan was afforded the opportunity to make his breakthrough hit Memento (2000). During a road trip from Chicago to Los Angeles, his brother Jonathan pitched the idea for "Memento Mori", about a man with anterograde amnesia who uses notes and tattoos to hunt for his wife's murderer. Nolan developed a screenplay that told the story in reverse; Aaron Ryder, an executive for Newmarket Films, said it was "perhaps the most innovative script I had ever seen".[38] The film was optioned and given a budget of $4.5 million.[39] Memento, starring Guy Pearce and Carrie-Anne Moss, premiered in September 2000 at the Venice International Film Festival to critical acclaim.[40] Joe Morgenstern of The Wall Street Journal wrote in his review, "I can't remember when a movie has seemed so clever, strangely affecting and slyly funny at the very same time."[41] Basil Smith, in the book The Philosophy of Neo-Noir, draws a comparison with John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding which argues that conscious memories constitute our identities, a theme which Nolan explores in the film.[42] The film was a box-office success[43] and received a number of accolades, including Academy Award and Golden Globe Award nominations for its screenplay, Independent Spirit Awards for Best Director and Best Screenplay, and a Directors Guild of America (DGA) Award nomination.[44][45] Memento was considered by numerous critics to be one of the best films of the 2000s.[46]

.jpg)

Impressed by his work on Memento, Steven Soderbergh recruited Nolan to direct the psychological thriller Insomnia (2002), starring Academy Award winners Al Pacino, Robin Williams and Hilary Swank.[47] Warner Bros. initially wanted a more seasoned director, but Soderbergh and his Section Eight Productions fought for Nolan, as well as his choice of cinematographer (Wally Pfister) and editor (Dody Dorn).[48] With a $46 million budget, it was described as "a much more conventional Hollywood film than anything the director has done before".[47] A remake of the 1997 Norwegian film of the same name, Insomnia is about two Los Angeles detectives sent to a northern Alaskan town to investigate the methodical murder of a local teenager. It received positive reviews from critics and performed well at the box office, earning $113 million worldwide.[49][50] Film critic Roger Ebert praised the film for introducing new perspectives and ideas on the issues of morality and guilt. "Unlike most remakes, the Nolan Insomnia is not a pale retread, but a re-examination of the material, like a new production of a good play."[51] Erik Skjoldbjærg, the director of the original film, was satisfied with Nolan's version, calling it a "well crafted, smart film ... with a really good director handling it".[52] Richard Schickel of Time deemed Insomnia a "worthy successor" to Memento, and "a triumph of atmosphere over a none-too-mysterious mystery."[53]

Transition to blockbuster films: 2003–2007

After Insomnia, Nolan planned a Howard Hughes biographical film starring Jim Carrey. He penned a screenplay, which he said was "the best script I've ever written", but when he learned that Martin Scorsese was making a Hughes biopic (2004's The Aviator) he reluctantly tabled his script and moved on to other projects.[54][55] Having turned down an offer to direct the historical epic Troy (2004),[56] Nolan worked on adapting Ruth Rendell's crime novel The Keys to the Street into a screenplay which he planned to direct for Fox Searchlight Pictures, but eventually left the project citing the similarities to his previous films.[57]

In early 2003, Nolan approached Warner Bros. with the idea to make a new Batman film. Fascinated by the character and story, he wanted to make a film grounded in a "relatable" world more reminiscent of a classical drama than a comic-book fantasy.[58] Batman Begins, the biggest project Nolan had undertaken to that point,[58] premiered in June 2005 to both critical acclaim and commercial success.[59] Starring Christian Bale in the title role, along with Michael Caine, Gary Oldman, Morgan Freeman, and Liam Neeson, the film revived the franchise, heralding a trend towards darker films which rebooted (or retold) backstories.[60][61] It tells the origin story of the character from Bruce Wayne's initial fear of bats, the death of his parents, his journey to become Batman, and his fight against Ra's al Ghul's plot to destroy Gotham City. Praised for its psychological depth and contemporary relevance,[62] Kyle Smith of The New York Post called it "a wake-up call to the people who keep giving us cute capers about men in tights. It wipes the smirk off the face of the superhero movie."[63] Batman Begins was the eighth-highest-grossing film of 2005 in the United States and the year's ninth-highest-grossing film worldwide.[64] It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Cinematography and three BAFTA awards.[65][66] On its 10th anniversary, Forbes published an article describing the film's influence: "Reboot became part of our modern vocabulary, and superhero origin stories became increasingly en vogue for the genre. The phrase "dark and gritty" likewise joined the cinematic lexicon, influencing our perception of different approaches to storytelling not only in the comic book film genre but in all sorts of other genres as well."[67]

Before returning to the Batman franchise, Nolan directed, co-wrote and produced The Prestige (2006), an adaptation of the Christopher Priest novel about two rival 19th-century magicians.[68] In 2001, when Nolan was in post-production for Insomnia, he asked his brother Jonathan to help write the script for the film. The screenplay was an intermittent, five-year collaboration between the brothers.[69] Nolan initially intended to make the film as early as 2003, postponing the project after agreeing to make Batman Begins.[70] Starring Christian Bale and Hugh Jackman in the lead roles, The Prestige received critical acclaim (including Oscar nominations for Best Cinematography and Best Art Direction),[71] and earned over $109 million worldwide.[72][73] Roger Ebert described it as "quite a movie — atmospheric, obsessive, almost satanic".[74] Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times called it an "ambitious, unnerving melodrama".[75] Philip French wrote in his review for The Guardian: "In addition to the intellectual or philosophical excitement it engenders, The Prestige is gripping, suspenseful, mysterious, moving and often darkly funny."[76] Following the release of The Prestige, Nolan was considering to direct a feature film adaptation of the British television series The Prisoner (1967), but later dropped out of the project.[77][78]

Mainstream success: 2008–2012

In July 2006, Nolan announced that the follow-up to Batman Begins would be called The Dark Knight.[79] Approaching the sequel, Nolan wanted to expand on the noirish quality of the first film by broadening the canvas and taking on "the dynamic of a story of the city, a large crime story ... where you're looking at the police, the justice system, the vigilante, the poor people, the rich people, the criminals."[80] Released in 2008 to great critical acclaim, The Dark Knight has been cited as one of the best films of the 2000s and one of the best superhero films ever made.[46][81][82] Manohla Dargis of The New York Times found the film to be of higher artistic merit than many Hollywood blockbusters: "Pitched at the divide between art and industry, poetry and entertainment, it goes darker and deeper than any Hollywood movie of its comic-book kind."[83] Ebert expressed a similar point of view, describing it as a "haunted film that leaps beyond its origins and becomes an engrossing tragedy."[84] Filmmaker Kevin Smith called it "the Godfather [Part] II of comic book films".[85] The Dark Knight set a number of box-office records during its theatrical run,[86] earning $534,858,444 in North America and $469,700,000 abroad, for a worldwide total of $1,004,558,444.[87] It is the first commercial feature film shot partially in the 15/70 mm IMAX format.[88] At the 81st Academy Awards the film was nominated for eight Oscars, winning two: the Academy Award for Best Sound Editing and a posthumous Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for Heath Ledger.[89] Nolan was recognised by his peers with nominations from the DGA, Writers Guild of America (WGA), and Producers Guild of America (PGA).[44]

After The Dark Knight's success, Warner Bros. signed Nolan to direct Inception. Nolan also wrote and co-produced the film, described as "a contemporary sci-fi actioner set within the architecture of the mind".[90] Before being released in theaters, critics like Peter Travers and Lou Lumenick wondered if Nolan's faith in moviegoers' intelligence would cost him at the box office.[91] Starring a large ensemble cast led by Leonardo DiCaprio, the film was released on 16 July 2010, and was a critical and commercial success.[92] Richard Roeper of the Chicago Sun-Times, awarded the film a perfect score of "A+" and called it "one of the best movies of the [21st] century."[93] Mark Kermode named it the best film of 2010, stating "Inception is proof that people are not stupid, that cinema is not trash, and that it is possible for blockbusters and art to be the same thing."[94] Veteran producer John Davis speculated that its success could inspire studios to make more original content; "I can promise you that heads of studios are already going into production meetings saying we need fresh ideas for summer movies, we want original concepts like Inception that are big and bold enough to carry themselves".[95] The film ended up grossing over $820 million worldwide[96] and was nominated for eight Oscars, including Best Picture; it won Best Cinematography, Best Sound Mixing, Best Sound Editing and Best Visual Effects.[97] Nolan also received BAFTA, Golden Globe, DGA and PGA Award nominations, as well as a WGA Award for his work on the film.[44] While in post-production on Inception, Nolan gave an interview for These Amazing Shadows (2011), a documentary spotlighting film appreciation and preservation by the National Film Registry.[98] He also appeared in Side by Side (2012), a documentary about the history, process and workflow of both digital and photochemical film creation.[99]

In 2012, Nolan directed his third and final Batman film, The Dark Knight Rises. Although he was initially hesitant about returning to the series, he agreed to come back after developing a story with his brother and David S. Goyer which he felt would end the series on a high note.[100][101] The Dark Knight Rises was released on 20 July 2012 to positive reviews; Andrew O'Hehir of Salon called it "arguably the biggest, darkest, most thrilling and disturbing and utterly balls-out spectacle ever created for the screen", further describing the work as "auteurist spectacle on a scale never before possible and never before attempted".[102] Christy Lemire of The Associated Press wrote in her review that Nolan concluded his trilogy in a "typically spectacular, ambitious fashion", but disliked the "overloaded" story and excessive grimness; "This is the problem when you're an exceptional, visionary filmmaker. When you give people something extraordinary, they expect it every time. Anything short of that feels like a letdown."[103] Like its predecessor it performed well at the box office, becoming the thirteenth film in the world to gross over $1-billion.[104][105] During a midnight showing of the film at the Century 16 cinema in Aurora, Colorado, a gunman opened fire inside the theater, killing 12 people and injuring 58 others.[106] Nolan released a statement to the press expressing his condolences for the victims of what he described as a senseless tragedy.[107]

Interstellar and film preservation: 2013–2015

During story discussions for The Dark Knight Rises in 2010, Goyer told Nolan of his idea to present Superman in a modern context.[108][109] Impressed with Goyer's first contact concept, Nolan pitched the idea for Man of Steel (2013) to Warner Bros,[108] who hired Nolan to produce and Goyer to write.[110][111] Nolan offered Zack Snyder to direct the film, based on his stylized adaptations of 300 (2007) and Watchmen (2009) and his "innate aptitude for dealing with superheroes as real characters".[112] Starring Henry Cavill, Amy Adams, Kevin Costner, Russell Crowe and Michael Shannon, Man of Steel grossed more than $660 million at the worldwide box office, but garnered a divided critical reaction.[113][114] Nolan and Thomas served as executive producers on Transcendence (2014), the directorial debut of Nolan's longtime cinematographer Wally Pfister.[115][116] Starring Johnny Depp, Rebecca Hall and Paul Bettany, Transcendence was released in theaters on 18 April 2014 to mostly unfavorable reviews.[117][118]

In January 2013, it was announced that Nolan would direct, write and produce a science-fiction film entitled Interstellar. The first drafts of the script were written by Jonathan Nolan, and it was originally to be directed by Steven Spielberg.[119] Based on the scientific theories of renowned theoretical physicist Kip Thorne, the film depicted "a heroic interstellar voyage to the farthest borders of our scientific understanding".[120] Interstellar starred Matthew McConaughey, Anne Hathaway, Jessica Chastain, Bill Irwin, Michael Caine and Ellen Burstyn, and was notably Nolan's first collaboration with cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema. Paramount Pictures and Warner Bros. co-financed and co-distributed the project, released on 5 November 2014 to largely positive reviews and strong box office results, grossing over $670 million worldwide.[121][122][123] A. O. Scott wrote, in his review for The New York Times, "Interstellar, full of visual dazzle, thematic ambition ... is a sweeping, futuristic adventure driven by grief, dread and regret."[124] It was also warmly reviewed by film critic James Berardinelli who noted: "The film deserves the label of an "experience" and the bigger the venue, the more immersive it will be. As event movies go, this is one of the most unique and mesmerizing."[125] Documentary filmmaker Toni Myers said of the film, "I loved it because it tackled the most difficult part of human exploration, which is that it's a multi-generational journey. It was a real work of art."[126] Interstellar was particularly praised for its scientific accuracy, which led to the publication of two scientific papers and the American Journal of Physics calling for it to be shown in school science lessons.[127] It was named one of the best films of the year by The American Film Institute (AFI).[128] At the 87th Academy Awards, the film won the Best Visual Effects and received four other nominations — Best Original Score, Best Sound Mixing, Best Sound Editing and Best Production Design.[129] Nolan curated the short film Emic: A Time Capsule From the People of Earth (2015). It was specifically inspired by the themes of Interstellar, and "attempts to capture and celebrate the human experience on Earth".[130][131]

In 2015, Nolan's production company Syncopy formed a joint venture with Zeitgeist Films, to release Blu-ray editions of Zeitgeist's prestige titles. Their first project was Elena (2011) from director Andrey Zvyagintsev.[132] As part of a Blu-ray release of the Quay brothers animated work, Nolan directed the documentary short Quay (2015). He also initiated a theatrical tour, showcasing the Quays' In Absentia, The Comb and Street of Crocodiles. The program and Nolan's short received critical acclaim, with Indiewire writing in their review that the brothers "will undoubtedly have hundreds, if not thousands more fans because of Nolan, and for that The Quay Brothers in 35mm will always be one of latter's most important contributions to cinema".[133][134] In 2015, Nolan joined The Film Foundation's board of directors, a non-profit organization dedicated to film preservation.[135] Having been instrumental in keeping the production of film stock alive in the 21st century, Nolan invited over 30 representatives from leading American film archives, labs and presenting institutions to participate in an informal summit entitled Reframing the Future of Film at the Getty Museum in March 2015.[136][137] On 7 May, it was announced that Nolan and Martin Scorsese had been appointed by the Library of Congress to serve on the National Film Preservation Board (NFPB) as DGA representatives.[138]

Recent work: 2016–present

Nolan and Thomas opted to take a step back and only serve as executive producers on Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016), the sequel to Man of Steel.[139][140] The film was a box office success, grossing $873 million, but received generally unfavorable reviews from critics.[141] Later that year, Nolan was featured in the documentary Cinema Futures (2016) by Austrian filmmaker Michael Palm.[142]

In December 2015, it was announced that Nolan would direct and produce a film titled Dunkirk, based on his own original screenplay. The story is set amid World War II and the evacuation of Allied soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk, France in 1940. During the year-long production of his first film, Following (1998), Nolan and Thomas hired a small sailing boat to take them across the English Channel and retrace the journey of the little ships of Dunkirk. "We did it at the same time of year to get a sense of what it was like, and it turned out to be an incredibly dangerous experience. And that was with no bombs dropping on us."[144] For Dunkirk, Nolan said he was inspired by the work of Robert Bresson, and silent films such as Intolerance (1916), Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927) and The Wages of Fear (1953).[145] Describing the film as a survival tale with a triptych structure, Nolan wanted to make a "sensory, almost experimental movie" with minimal dialogue.[146] Starring Fionn Whitehead, Jack Lowden, Aneurin Barnard, Harry Styles, Tom Hardy, Mark Rylance, Cillian Murphy and Kenneth Branagh,[147] Dunkirk was released in theaters on 21 July 2017 to widespread critical acclaim and strong box office results.[148][149][150] Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote in his review: "It's one of the best war films ever made, distinct in its look, in its approach and in the effect it has on viewers. There are movies—they are rare—that lift you out of your present circumstances and immerse you so fully in another experience that you watch in a state of jaw-dropped awe. Dunkirk is that kind of movie." Manohla Dargis of The New York Times lauded the film, calling it "a tour de force of cinematic craft and technique, but one that is unambiguously in the service of a sober, sincere, profoundly moral story that closes the distance between yesterday's fights and today's."[151]

Filmmaking

Style

Regarded as an auteur filmmaker,[152][153] Nolan's visual style often emphasises urban settings, men in suits, muted colours, dialogue scenes framed in wide close-up with a shallow depth of field and modern locations and architecture. Aesthetically, the director favours deep, evocative shadows, documentary-style lighting, natural settings and real filming locations over studio work.[154] Nolan has noted that many of his films are heavily influenced by film noir.[155] He has continuously experimented with metafictive elements, temporal shifts, elliptical cutting, solipsistic perspectives, nonlinear storytelling, labyrinthine plots and the merging of style and form.[155][156][157][158] Discussing The Tree of Life (2011), Nolan spoke of Terrence Malick's work and how it has influenced his own approach to style, "When you think of a visual style, when you think of the visual language of a film, there tends to be a natural separation of the visual style and the narrative elements. But with the greats, whether it's Stanley Kubrick or Terrence Malick or Hitchcock, what you're seeing is an inseparable, a vital relationship between the image and the story it's telling".[159]

Drawing attention to the intrinsically manipulative nature of the medium, Nolan uses narrative and stylistic techniques (notably mise en abyme and recursions) to stimulate the viewer to ask themselves why his films are put together in such ways and why the films provoke particular responses.[160] He sometimes uses editing as a way to represent the characters' psychological states, merging their subjectivity with that of the audience.[161] For example, in Memento the fragmented sequential order of scenes is to put the audience into a similar experience of Leonard's defective ability to create new long-term memories. In The Prestige, the series of magic tricks and themes of duality and deception mirror the structural narrative of the film.[155] His writing style incorporates a number of storytelling techniques such as flashbacks, shifting points of view and unreliable narrators. Scenes are often interrupted by the unconventional editing style of cutting away quickly from the money shot (or nearly cutting off characters' dialogue) and crosscutting several scenes of parallel action to build to a climax.[155][162] In 2017, noted film theorist and historian David Bordwell wrote about Nolan's fascination with subjective storytelling and crosscutting, "It's rare to find any mainstream director so relentlessly focused on exploring a particular batch of storytelling techniques ... Nolan zeroes in, from film to film, on a few narrative devices, finding new possibilities in what most directors handle routinely. He seems to me a very thoughtful, almost theoretical director in his fascination with turning certain conventions this way and that, to reveal their unexpected possibilities."[163]

Nolan has also stressed the importance of establishing a clear point of view in his films, and makes frequent use of "the shot that walks into a room behind a character, because ... that takes [the viewer] inside the way that the character enters".[29] He has also used cinéma-vérité techniques (such as hand-held camera work) to convey realism.[164] In an interview at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, he explained his emphasis on realism in The Dark Knight trilogy: "You try and get the audience to invest in cinematic reality. When I talk about reality in these films, it's often misconstrued as a direct reality, but it's really about a cinematic reality."[165]

In collaboration with composer David Julyan, Nolan's films featured slow and atmospheric scores with minimalistic expressions and ambient textures. In the mid-2000s, starting with Batman Begins, Nolan began working with Hans Zimmer, who is known for integrating electronic music with traditional orchestral arrangements. With Zimmer, the soundscape in Nolan's films evolved into becoming increasingly more lush, kinetic and experimental.[166] An example of this is the main theme from Inception, which is derived from a slowed down version of Edith Piaf's song Non, je ne regrette rien.[167] For 2014's Interstellar, Zimmer and Nolan wanted to move in a new direction: "The textures, the music, and the sounds, and the thing we sort of created has sort of seeped into other people's movies a bit, so it's time to reinvent."[168] The score for Dunkirk (2017) was written to accommodate the auditory illusion of a Shepard tone, as well as being based on a recording of Nolan's own pocket watch, which he sent to Zimmer to be synthesised.[167] Responding to some criticism over his "experimental" sound mix for Interstellar, Nolan said, "I've always loved films that approach sound in an impressionistic way and that is an unusual approach for a mainstream blockbuster ... I don't agree with the idea that you can only achieve clarity through dialogue. Clarity of story, clarity of emotions — I try to achieve that in a very layered way using all the different things at my disposal — picture and sound."[169]

Method

—Nolan, on sincerity and ambition in filmmaking.

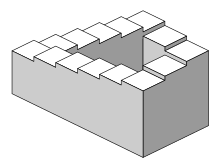

Nolan has described his filmmaking process as a combination of intuition and geometry. "I draw a lot of diagrams when I work. I do a lot of thinking about etchings by Escher, for instance. That frees me, finding a mathematical model or a scientific model. I'll draw pictures and diagrams that illustrate the movement or the rhythm that I'm after."[171] Caltech physicist Kip Thorne compared Nolan's "deep" intuition to scientists such as Albert Einstein, noting that the director intuitively grasped things non-scientists rarely understand.[172] Upon his own decision-making of whether or not to start work on a project, the filmmaker has proclaimed a belief in the sincerity of his passion for something within the particular project in question as a basis for his selective thought.[173]

He prefers shooting on film to digital video, and opposes the use of digital intermediates and digital cinematography, which he feels are less reliable and offer inferior image quality to film. In particular, the director advocates for the use of higher-quality, larger-format film stock such as anamorphic 35 mm, VistaVision, 65 mm and IMAX.[29][174] Nolan uses multi-camera for stunts and single-camera for all the dramatic action, from which he will then watch dailies every night; "Shooting single-camera means I've already seen every frame as it's gone through the gate because my attention isn't divided to multi-cameras."[29]

When working with actors, Nolan prefers giving them the time to perform as many takes of a given scene as they want. "I've come to realize that the lighting and camera setups, the technical things, take all the time, but running another take generally only adds a couple of minutes. ... If an actor tells me they can do something more with a scene, I give them the chance, because it's not going to cost that much time. It can't all be about the technical issues."[29] Gary Oldman praised the director for providing a relaxed atmosphere on set, adding "I've never seen him raise his voice to anyone". He also observed that Nolan would give the actors space to "find things in the scene", and not just give direction for direction's sake.[175]

Nolan chooses to minimize the amount of computer-generated imagery for special effects in his films, preferring to use practical effects whenever possible, only using CGI to enhance elements which he has photographed in camera. For instance his films Batman Begins, Inception and Interstellar featured 620, 500 and 850 visual-effects shots, respectively, which is considered minor when compared with contemporary visual-effects epics which may have upwards of 1,500 to 2,000 VFX shots:[176] "I believe in an absolute difference between animation and photography. However sophisticated your computer-generated imagery is, if it's been created from no physical elements and you haven't shot anything, it's going to feel like animation. There are usually two different goals in a visual effects movie. One is to fool the audience into seeing something seamless, and that's how I try to use it. The other is to impress the audience with the amount of money spent on the spectacle of the visual effect, and that, I have no interest in".[29]

Nolan shoots the entirety of his films with one unit, rather than using a second unit for action sequences. In that way Nolan keeps his personality and point of view in every aspect of the film. "If I don't need to be directing the shots that go in the movie, why do I need to be there at all? The screen is the same size for every shot ... Many action films embrace a second unit taking on all of the action. For me, that's odd because then why did you want to do an action film?"[29] A famously secretive filmmaker, Nolan is also known for his tight security on scripts, even going as far as telling the actors of The Dark Knight Rises the ending of the film verbally to avoid any leaks and also keeping the Interstellar plot secret from his composer Hans Zimmer.[177][178][179]

The director deliberately works under a tight schedule during the early stages of the editing process, forcing himself and his editor to work more spontaneously. "I always think of editing as instinctive or impressionist. Not to think too much, in a way, and feel it more."[171] Nolan also avoids using temp music while cutting his films.[180]

Themes

Nolan's work explores existential, ethical and epistemological themes such as subjective experience, distortion of memory, human morality, the nature of time, causality and construction of personal identity.[181] "I'm fascinated by our subjective perception of reality, that we are all stuck in a very singular point of view, a singular perspective on what we all agree to be an objective reality, and movies are one of the ways in which we try to see things from the same point of view".[170][182] Film critic Tom Shone described Nolan's oeuvre as "epistemological thrillers whose protagonists, gripped by the desire for definitive answers, must negotiate mazy environments in which the truth is always beyond their reach."[4] In an essay titled The rational wonders of Christopher Nolan, film critic Mike D'Angelo argues that the filmmaker is a materialist dedicated to exploring the wonders of the natural world. "Underlying nearly every film he's ever made, no matter how fanciful, is his conviction that the universe can be explained entirely by physical processes."[183]

His characters are often emotionally disturbed, obsessive and morally ambiguous, facing the fears and anxieties of loneliness, guilt, jealousy, and greed; in addition to the larger themes of corruption and conspiracy. By grounding "everyday neurosis – our everyday sort of fears and hopes for ourselves" in a heightened reality, Nolan makes them more accessible to a universal audience.[184] The protagonists of Nolan's films are often driven by philosophical beliefs, and their fate is ambiguous.[185] In some of his films, the protagonist and antagonist are mirror images of each other, a point which is made to the protagonist by the antagonist. Through these clashings of ideologies, Nolan highlights the ambivalent nature of truth.[160] The director also uses his real-life experiences as an inspiration in his work, "From a creative point of view, the process of growing up, the process of maturing, getting married, having kids, I've tried to use that in my work. I've tried to just always be driven by the things that were important to me."[186] Writing for The Playlist, Oliver Lyttelton singled out parenthood as a signature theme in Nolan's work, adding; "the director avoids talking about his private life, but fatherhood has been at the emotional heart of almost everything he's made, at least from Batman Begins onwards (previous films, it should be said, pre-dated the birth of his kids)."[187]

Nolan's most prominent recurring theme is the concept of time. The director has identified that all of his films "have had some odd relationship with time, usually in just a structural sense, in that I have always been interested in the subjectivity of time."[188] Writing for Film Philosophy, Emma Bell points out that the characters in Inception do not literally time-travel, "rather they escape time by being stricken in it – building the delusion that time has not passed, and is not passing now. They feel time grievously: willingly and knowingly destroying their experience by creating multiple simultaneous existences."[160] In Interstellar, Nolan explored the laws of physics as represented in Einstein's theory of general relativity, identifying time as the film's antagonist.[189] Reality is often an abstract and fragile concept in Nolan's work. Alec Price and M. Dawson of Left Field Cinema, noted that the existential crisis of conflicted male figures "struggling with the slippery nature of identity" is a prevalent theme in Nolan's work. The actual (or objective) world is of less importance than the way in which we absorb and remember, and it is this created (or subjective) reality that truly matters. "It is solely in the mind and the heart where any sense of permanency or equilibrium can ever be found."[156] According to film theorist Todd McGowan, these "created realities" also reveal the ethical and political importance of creating fictions and falsehoods. Nolan's films typically deceive spectators about the events that occur and the motivations of the characters, but they do not abandon the idea of truth altogether. Instead, "They show us how truth must emerge out of the lie if it is not to lead us entirely astray." McGowan further argues that Nolan is the first filmmaker to devote himself entirely to the illusion of the medium, calling him a Hegelian filmmaker.[190] He has also noted that retroactive causality populates many of Nolan's films.[191]

The Dark Knight trilogy explored themes of chaos, terrorism, escalation of violence, financial manipulation, utilitarianism, mass surveillance, and class conflicts.[157][192] Batman's arc of rising (philosophically) from a man to "more than just a man", is similar to the Nietzschian Übermensch.[193][194] The films also explore ideas akin to Jean-Jacques Rousseau's philosophical glorification of a simpler, more-primitive way of life and the concept of general will.[195] Theorist Douglas Kellner saw the series as a critical allegory about the Bush-Cheney era, highlighting the theme of government corruption and failure to solve social problems, as well as the cinematic spectacle and iconography related to 9/11.[196] In Inception, Nolan was inspired by lucid dreaming and dream incubation.[197] The film's characters try to embed an idea in a person's mind without their knowledge, similar to Freud's theories that the unconscious influences one's behavior without their knowledge.[198] Most of the film takes place in interconnected dream worlds; this creates a framework where actions in the real (or dream) worlds ripple across others. The dream is always in a state of emergence, shifting across levels as the characters navigate it.[199] Inception, like Memento and The Prestige, uses metaleptic storytelling devices and follows Nolan's "auteur affinity of converting, moreover, converging narrative and cognitive values into and within a fictional story."[200]

Influences

The filmmaker has often cited Dutch graphic artist M. C. Escher as a major influence on his own work. "I'm very inspired by the prints of M. C. Escher and the interesting connection-point or blurring of boundaries between art and science, and art and mathematics."[201] Another source of inspiration is Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges. The director has called Memento a "strange cousin" to Funes the Memorious, and has said "I think his writing naturally lends itself to a cinematic interpretation because it is all about efficiency and precision, the bare bones of an idea."[202]

Nolan has cited Stanley Kubrick,[203][204] Michael Mann,[205] Terrence Malick,[204] Orson Welles,[206] Fritz Lang,[207] Nicolas Roeg,[207] Sidney Lumet,[207] David Lean,[208] Ridley Scott,[29] Terry Gilliam,[206] and John Frankenheimer[209] as influences. Nolan's personal favorite films include Blade Runner (1982), Star Wars (1977), The Man Who Would Be King (1975), Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Chinatown (1974), and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).[210] In 2013, Criterion Collection released a list of Nolan's ten favorite films from its catalog, which included The Hit (1984), 12 Angry Men (1957), The Thin Red Line (1998), The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), Bad Timing (1980), Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence (1983), For All Mankind (1989), Koyaanisqatsi (1982), Mr. Arkadin (1955), and Erich von Stroheim's Greed (1924) (unavailable on Criterion).[211] He is also a big fan of the James Bond movies.[212]

Nolan's habit for employing non-linear storylines was particularly influenced by the Graham Swift novel Waterland, which he felt "did incredible things with parallel timelines, and told a story in different dimensions that was extremely coherent". He was also influenced by the visual language of the film Pink Floyd – The Wall (1982) and the structure of Pulp Fiction (1994), stating that he was "fascinated with what Tarantino had done".[29] Dante's Inferno, the Labyrinth and the Minotaur served as influences for Inception.[213] For Interstellar he mentioned a number of literary influences, including Flatland by Edwin Abbott Abbott, The Wasp Factory by Iain Banks, and Madeleine L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time.[214] Other influences Nolan has credited include figurative painter Francis Bacon,[215] architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and authors Raymond Chandler, James Ellroy, Jim Thompson[14] and Charles Dickens (A Tale of Two Cities was a major influence on The Dark Knight Rises).[216]

Views on the film industry

Christopher Nolan is a vocal proponent for the continued use of film stock over digital recording and projection formats, summing up his beliefs as, "I am not committed to film out of nostalgia. I am in favor of any kind of technical innovation but it needs to exceed what has gone before and so far nothing has exceeded anything that's come before".[217] Nolan's major concern is that the film industry's adoption of digital formats has been driven purely by economic factors as opposed to digital being a superior medium to film, saying: "I think, truthfully, it boils down to the economic interest of manufacturers and [a production] industry that makes more money through change rather than through maintaining the status quo."[29]

.jpg)

Shortly before Christmas of 2011, Nolan invited several prominent directors, including, Edgar Wright, Michael Bay, Bryan Singer, Jon Favreau, Eli Roth, Duncan Jones and Stephen Daldry, to Universal CityWalk's IMAX theatre for a private screening of the first six minutes of The Dark Knight Rises, which had been shot on IMAX film and edited from the original camera negative. Nolan used this screening in an attempt to showcase the superiority of the IMAX format over digital, and warn the filmmakers that unless they continued to assert their choice to use film in their productions, Hollywood movie studios would begin to phase out the use of film in favor of digital.[29][218] Nolan explained; "I wanted to give them a chance to see the potential, because I think IMAX is the best film format that was ever invented. It's the gold standard and what any other technology has to match up to, but none have, in my opinion. The message I wanted to put out there was that no one is taking anyone's digital cameras away. But if we want film to continue as an option, and someone is working on a big studio movie with the resources and the power to insist [on] film, they should say so. I felt as if I didn't say anything, and then we started to lose that option, it would be a shame. When I look at a digitally acquired and projected image, it looks inferior against an original negative anamorphic print or an IMAX one."[29] Nolan has lent out IMAX lenses from his personal collection to fellow directors to use on movies including Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015).[219]

Nolan is also an advocate for the importance of films being shown in large screened cinema theaters as opposed to home video formats, as he believes that, "The theatrical window is to the movie business what live concerts are to the music business—and no one goes to a concert to be played an MP3 on a bare stage."[220] In 2014, Christopher Nolan wrote an article for The Wall Street Journal where he expressed concern that as the film industry transitions away from photochemical film towards digital formats, the difference between seeing films in theaters versus on other formats will become trivialized, leaving audiences no incentive to seek out a theatrical experience. Nolan further expressed concern that with content digitized, theaters of the future will be able to track best-selling films and adjust their programming accordingly; a process that favors large heavily marketed studio films, but will marginalize smaller innovative and unconventional pictures. In order to combat this, Nolan believes the industry needs to focus on improving the theatrical experience with bigger and more beautiful presentation formats that cannot be accessed or reproduced in the home, as well as embracing the new generation of aspiring young innovative filmmakers.[220]

Recurring collaborators

Emma Thomas has co-produced all of his films (including Memento, in which she is credited as an associate producer). He regularly works with his brother, Jonathan Nolan (creator of Person of Interest and Westworld), who describes their working relationship in the production notes for The Prestige: "I've always suspected that it has something to do with the fact that he's left-handed and I'm right-handed, because he's somehow able to look at my ideas and flip them around in a way that's just a little bit more twisted and interesting. It's great to be able to work with him like that".[221] When working on separate projects the brothers always consult each other.[222]

.jpg)

—Nolan on collaboration and leadership.[223]

The director has worked with screenwriter David S. Goyer on all his comic-book adaptations.[224] Wally Pfister was the cinematographer for all of Nolan's films from Memento to The Dark Knight Rises.[225] Embarking on his own career as a director, Pfister said: "The greatest lesson I learned from Chris Nolan is to keep my humility. He is an absolute gentleman on set and he is wonderful to everyone — from the actors to the entire crew, he treats everyone with respect."[226] Lee Smith has been Nolan's editor since Batman Begins, with Dody Dorn editing Memento and Insomnia.[227] David Julyan composed the music for Nolan's early work, while Hans Zimmer and James Newton Howard provided the music for Batman Begins and The Dark Knight.[228] Zimmer scored The Dark Knight Rises, and has worked with Nolan on his subsequent films.[229] Zimmer has said his creative relationship with Nolan is highly collaborative, and that he views Nolan as "the co-creator of the score".[230] The director has worked with sound designer Richard King and sound mixer Ed Novick since The Prestige.[231] Nolan has frequently collaborated with special-effects supervisor Chris Corbould,[232] stunt coordinator Tom Struthers[233] first assistant director Nilo Otero,[234] and visual effects supervisor Paul Franklin.[235] Production designer Nathan Crowley has worked with him since Insomnia (except for Inception).[236] Nolan has called Crowley one of his closest and most inspiring creative collaborators.[237] Casting director John Papsidera has worked on all of Nolan's films, except Following and Insomnia.[238]

Christian Bale, Michael Caine, Cillian Murphy and Tom Hardy have been frequent collaborators since the mid-2000s. Caine is Nolan's most prolific collaborator, having appeared in seven of his films, and is regarded by Nolan to be his "good luck charm".[239] In return, Caine has described Nolan as "one of cinema's greatest directors", comparing him favorably with the likes of David Lean, John Huston and Joseph L. Mankiewicz.[240][241][242] Nolan is also known for casting stars from the 1980s in his films, i.e. Rutger Hauer (Batman Begins), Eric Roberts (The Dark Knight), Tom Berenger (Inception), and Matthew Modine (The Dark Knight Rises).[243] Modine said of working with Nolan: "There are no chairs on a Nolan set, he gets out of his car and goes to the set. And he stands up until lunchtime. And then he stands up until they say 'Wrap'. He's fully engaged – in every aspect of the film."[244]

Personal life

Nolan is married to Emma Thomas, whom he met at University College London when he was 19.[13][22] She has worked as a producer on all of his films, and together they founded the production company Syncopy Inc.[245] The couple have four children and reside in Los Angeles.[246][247]

Protective of his privacy, he rarely discusses his personal life in interviews.[248] However, he has publicly shared some of his sociopolitical concerns for the future, such as the current conditions of nuclear weapons and environmental issues that he says need to be addressed.[249] He has also expressed a thrilling admiration for scientific objectivity, wishing it were to be applied "in every aspect of our civilization."[250]

Nolan prefers not to use a cell phone or an email address,[251] saying "It's not that I'm a Luddite and don't like technology; I've just never been interested [...] When I moved to Los Angeles in 1997, nobody really had cell phones, and I just never went down that path."[252] He also prohibits use of phones on set.[253]

Recognition

Having made some of the most influential and popular films of his time,[254] Nolan's work has been as "intensely embraced, analyzed and debated by ordinary film fans as by critics and film academics".[248][255] According to The Wall Street Journal, his "ability to combine box-office success with artistic ambition has given him an extraordinary amount of clout in the industry."[256] Geoff Andrew of the British Film Institute (BFI) and regular contributor to the Sight & Sound magazine, called Nolan "a persuasively inventive storyteller", singling him out as one of few contemporary filmmakers producing highly personal films within the Hollywood mainstream. He also pointed out that Nolan's films are as notable for their "considerable technical virtuosity and visual flair" as for their "brilliant narrative ingenuity and their unusually adult interest in complex philosophical questions."[257][258] Film scholar David Bordwell compared Nolan to Stanley Kubrick, citing his ability to turn genre movies into both art and event films.[163] Scott Foundas of Variety declared him "the premier big-canvas storyteller of his generation."[259]

The filmmaker has been praised by many of his contemporaries, and some have cited his work as influencing their own. Rupert Wyatt, director of Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011), said in an interview that he thinks of Nolan as a "trailblazer ... he is to be hugely admired as a master filmmaker, but also someone who has given others behind him a stick to beat back the naysayers who never thought a modern mass audience would be willing to embrace story and character as much as spectacle".[260] Michael Mann complimented Nolan for his "singular vision" and called him "a complete auteur". Nicolas Roeg said of Nolan, "[His] films have a magic to them ... People talk about 'commercial art' and the term is usually self-negating; Nolan works in the commercial arena and yet there's something very poetic about his work."[261]

Olivier Assayas said he admired Nolan for "making movies that are really unlike anything else. The way I see it, he has a really authentic voice."[262] Discussing the difference between art films and big-studio films, Steven Spielberg referred to Nolan's Dark Knight series as an example of both;[263] he has described Memento and Inception as "masterworks".[264] Nolan has also been commended by James Cameron,[265] Guillermo del Toro,[266] Matt Reeves,[267] Danny Boyle,[268] Wong Kar-Wai,[269] Steven Soderbergh,[270] Sam Mendes,[271] Martin Scorsese,[272] Werner Herzog,[273] Matthew Vaughn,[274] Paul Thomas Anderson,[275] Paul Greengrass,[276] Rian Johnson,[277] and others.[278] Noted film critic Mark Kermode complimented the director for bringing "the discipline and ethics of art-house independent moviemaking" to Hollywood blockbusters, calling him "[The] living proof that you don't have to appeal to the lowest common denominator to be profitable".[279]

In 2007, Total Film named Nolan the 32nd greatest director of all time,[280] and in 2012, The Guardian ranked him # 14 on their list of "The 23 Best Film Directors in the World"[281] The following year, Entertainment Weekly named him the 12th greatest working director.[282] He was ranked No. 2 on the same list in 2011.[283] A survey of 17 academics held in 2013, regarding which filmmakers had been referenced the most in essays and dissertations marked over the last five years, showed that Nolan was the second-most studied director in the UK after Quentin Tarantino and ahead of Alfred Hitchcock, Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg.[284] Nolan's work has also been recognised as an influence on video games.[285][286] In 2015, Time featured him as one of the "100 Most Influential People in the World".[287]

Awards and honors

As a writer and director of a number of science fiction and action films, Nolan has been honored with awards and nominations from the World Science Fiction Society (Hugo Awards), the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (Nebula Awards), and the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films (Saturn Awards).

Nolan screened Following at the 1999 Slamdance Film Festival, and won the Black & White Award. In 2014, he received the first-ever Founder's Award from the Festival. "Throughout his incredible successes, Christopher Nolan has stood firmly behind the Slamdance filmmaking community. We are honored to present him with Slamdance's inaugural Founder's Award", said Slamdance president and co-founder Peter Baxter.[288] At the 2001 Sundance Film Festival, Nolan and his brother Jonathan won the Waldo Salt Screenwriting Award for Memento, and in 2003, Nolan received the Sonny Bono Visionary Award from the Palm Springs International Film Festival. Festival executive director Mitch Levine said, "Nolan had in his brief time as a feature film director, redefined and advanced the very language of cinema".[289] He was named an Honorary Fellow of UCL in 2006; a title given out to individuals "who have attained distinction in the arts, literature, science, business or public life".[290]

In 2009, the director received the Board of the Governors Award from the American Society of Cinematographers. ASC president Daryn Okada said, "Chris Nolan is infused with talent with which he masterfully uses to collaboratively create memorable motion pictures ... his quest for superlative images to tell stories has earned the admiration of our members".[291] In 2011, Nolan received the Britannia Award for Artistic Excellence in Directing from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts[292] and the ACE Golden Eddie Filmmaker of the Year Award from American Cinema Editors.[293] That year he also received the Modern Master Award, the highest honor presented by the Santa Barbara International Film Festival. The executive director of the festival Roger Durling stated: "Every one of Nolan's films has set a new standard for the film community, with Inception being the latest example".[294] In addition, Nolan was the recipient of the inaugural VES Visionary Award from the Visual Effects Society.[295] In July 2012, he became the youngest director to be honored with a hand-and-footprint ceremony at Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Los Angeles.[296]

The Art Directors Guild (ADG) selected Nolan as the recipient of its Cinematic Imagery Award in 2015, an honor given to those whose body of work has "richly enhanced the visual aspects of the movie-going experience."[297] He was selected as the 2015 Class Day speaker at Princeton University. "Nolan, more than a film producer, is a thinker and visionary in our age and we are thrilled to have him deliver the keynote address," said Class Day co-chair Hanna Kim.[298] Nolan was awarded the Empire Inspiration Award at the 20th Empire Awards.[299] The director was also honored with a retrospective at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.[300] On 3 May 2017, Nolan received the 2017 FIAF Award before a special 70mm screening of Interstellar at the Samuel Goldwyn Theater in Beverly Hills.[301]

Filmography

Directorial work

| Year | Title | Also credited as | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producer | Writer | Other | |||

| 1989 | Tarantella | Yes | Yes | N/A | Unreleased short film |

| 1995 | Larceny | Yes | Yes | N/A | Unreleased short film |

| 1997 | Doodlebug | Yes | Yes | Yes[I][II] | Short film |

| 1998 | Following | Yes | Yes | Yes[I][II] | |

| 2000 | Memento | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2002 | Insomnia | Uncredited co-writer[302] | |||

| 2005 | Batman Begins | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2006 | The Prestige | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2008 | The Dark Knight | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2010 | Inception | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2012 | The Dark Knight Rises | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2014 | Interstellar | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2015 | Quay | Yes | Yes[I][II][III] | Documentary short | |

| 2017 | Dunkirk | Yes | Yes | ||

^ I Credited as editor

^ II Credited as cinematographer

^ III Credited as composer

Other projects

| Year | Title | Credited as | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producer | Writer | Other | |||

| 1997 | Fearville | Yes | Camera operator | ||

| 1999 | Genghis Blues | Yes | Assistant editor | ||

| 2011 | These Amazing Shadows | Himself | Documentary | ||

| 2012 | Side by Side | Himself | Documentary | ||

| 2013 | Man of Steel | Yes | Story | ||

| 2014 | Transcendence | Executive | |||

| 2016 | Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice | Executive | |||

| Cinema Futures | Himself | Documentary | |||

Reception

Critical, public and commercial reception to Nolan's directorial features.

- As of 10 August 2017

| Film | Rotten Tomatoes[303] | Metacritic[304] | BFCA[305] | CinemaScore[306] | Budget | Box office[307] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Following | 78% | 60 | N/A | N/A | $6 thousand | $48.4 thousand |

| Memento | 92% | 80 | 90/100 | N/A | $4 million | $39.7 million |

| Insomnia | 92% | 78 | 93/100 | B | $46 million | $113.7 million |

| Batman Begins | 84% | 70 | 91/100 | A | $150 million | $374.2 million |

| The Prestige | 76% | 66 | 83/100 | B | $40 million | $109.6 million |

| The Dark Knight | 94% | 82 | 96/100 | A | $185 million | $1.005 billion |

| Inception | 86% | 74 | 94/100 | B+ | $160 million | $825.5 million |

| The Dark Knight Rises | 87% | 78 | 91/100 | A | $250 million | $1.085 billion |

| Interstellar | 71% | 74 | 80/100 | B+ | $165 million | $675.1 million |

| Dunkirk | 93% | 94 | 90/100 | A− | $100 million | $319.6 million |

In 2008, four of his (then six) films featured in Empire magazine's list of the 500 greatest movies of all time.[308] In 2016, Memento, The Dark Knight, and Inception appeared in BBC's 100 Greatest Films of the 21st Century list.[309]

References

- ↑ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan". British Film Institute (BFI). Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ↑ "Nolan's Mind Games". Film London. 14 July 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 Shone, Tom (4 November 2014). "Christopher Nolan: the man who rebooted the blockbuster". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "Batman, robbin' and murder". The Sunday Times. 27 June 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ "Can't get him out of our heads" The Age; retrieved 10 April 2011.

- 1 2 Feinberg, Scott (3 January 2015). "Christopher Nolan on 'Interstellar' Critics, Making Original Films and Shunning Cell Phones and Email (Q&A)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan injects his sci-fi with soul". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ↑ Boucher, Geoff (11 April 2010). "Christopher Nolan's 'Inception' — Hollywood's first existential heist film". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ↑ Itzkoff, Dave (30 June 2010). "The Man Behind the Dreamscape". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan's Inception tops British box office". BBC. 22 July 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ "Nolan sentenced for escape attempt". Chicago Tribune. 7 July 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 Lawrence, Will (19 July 2012). "Christopher Nolan interview for Inception". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 Timberg, Scott (15 March 2001). "Indie Angst". New Times Los Angeles. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ "Nolan's move from Highgate to Hollywood", Evening Standard (London); retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan’s final frontier". Andrew Purcell. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ↑ Covert, Colin. "Christopher Nolan explains his 'cinematic brain' at Walker Art Center". StarTribune. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ↑ "Genghis Blues". Musicdoc.se. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ O'Sullivan, Graydon (2013), p. 67.

- ↑ "Remembering My Brother Dan Eldon: A Journalist Who Died To Tell the Story". Huffingtonpost. 7 December 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 Tempest, M. "I was there at the 'Inception' of Christopher Nolan's film career", The Guardian, 24 February 2011; retrieved 21 September 2011.

- 1 2 "Wally Pfister ASC on Christopher Nolan's Inception". thecinematographer.info. 2010. Archived from the original on 11 April 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "The Filmmakers". Next Wave Films. 21 November 1999. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan: The Movies. The Memories". Empire. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "UCLU Film Society, London". Ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Fearville (1997)". BFI. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan’s First Released Short Film ‘Doodlebug’: Watch His Twisted 1997 Debut". IndieWire.

- ↑ Pulver, Andrew (15 June 2005). "He's not a god - he's human". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Ressner, Jeffrey (Spring 2012). "The Traditionalist". DGA Quarterly. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ "The Man behind the Mask". UCL. 8 December 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Interview with Christopher Nolan". Metro; retrieved 10 April 2011.

- 1 2 Duncker, Johannes (6 June 2002). "The Making of Following". christophernolan.net. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Tobias, S. Interview: Christopher Nolan, avclub.com, 5 June 2002; retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ↑ "Tiger Awards Competition: previous winners". International Film Festival Rotterdam. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Awards for Following". IMDB; retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ↑ Maslin, Janet. "Hero With No Memory Turns 'Memento' Into Unforgettable Trip". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ↑ "Criterion – Following". Criterion. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Mottram, p. 176.

- ↑ Mottram, p. 177.

- ↑ Mottram, p. 62–4.

- ↑ Morgenstern, Joe. "Hero With No Memory Turns 'Memento' Into Unforgettable Trip". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ↑ Conard (2007) p.35.

- ↑ "Memento". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Christopher Nolan awards". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ↑ Session Timeout – Academy Awards® Database Archived 5 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. (29 January 2010); retrieved 26 November 2011.

- 1 2 "Film Critics Pick the Best Movies of the Decade". Metacritic. 3 January 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- 1 2 "'Memento' recognition landed Christopher Nolan in the director's chair for big-budget 'Insomnia'". Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ deWaard, Tait (2013), p. 49.

- ↑ "Insomnia". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ "Insomnia". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (24 May 2002). "Insomnia review". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Paul Weedon. "Erik Skjoldbærg on 'Pioneer'". Grolsch Filmworks. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ↑ Schickel, Richard (19 May 2002). "Sleepless in Alaska". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan Talks Howard Hughes Project, 'Interstellar' & More In Interviews, Plus Featurettes, New Pics & More". Indiewire. 10 November 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan Says His Howard Hughes Film Is Dead, But He'd Still Like To Do A Bond Film at Some Point". Indiewire. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ↑ Jagernauth, Kevin. "Trivia: When Christopher Nolan First Came To Warner Bros., He Was Offered 'Troy' To Direct". The Playlist. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ Gemma Arterton to star in Christopher Nolan-penned thriller 'The Keys to the Street', Meeting with Ridley Scott for 'Alien' prequels' The Playlist, 9 June 2011.

- 1 2 "Christopher Nolan looks back over the Dark Knight trilogy in this extended interview". Filmcomment. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ↑ "Insomnia". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ "The Complicated Legacy of Batman Begins". The Atlantic. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ Shawn Adler (14 August 2008). "He-Man' Movie Will Go Realistic: 'We're Not Talking About Putting Nipples On The Trapjaw Suit". Archived from the original on 2 September 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan Season at BFI Southbank in July 2012" (PDF). British Film Institute. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ↑ "Review: Batman Begins". The New York Post. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ "Batman Begins (2005)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ "Batman Begins". IMDb.

- ↑ "Batman Begins". BAFTA-Awards Database. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ↑ "Exclusive: Christopher Nolan Talks 'Batman Begins' 10th Anniversary". Forbes. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ↑ "Interview about The Prestige". Christopher-priest.co.uk. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ↑ Jeff Goldsmith (28 October 2006). "The Prestige Q&A: Interview with Jonathan Nolan". Creative Screenwriting Magazine Podcast (Podcast). Creative Screenwriting. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ↑ "Nolan wants 'Prestige'". Variety. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Prestige". The Guardian.

- ↑ "The Prestige (2006)", Box Office Mojo; retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ↑ Murray, Noel. (3 December 2009) The best films of the '00s|Best of the Decade. The A.V. Club; retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ↑ "The Prestige". Roger Ebert. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ "They've got something up their sleeves". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ↑ "The Prestige". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ↑ "Exclusive: Nolan's Dark Knight Revelations". IGN. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ Child, Ben (12 February 2009). "Nolan signs to take Inception from script to screen". The Guardian. London, UK.

- ↑ Garth Franklin (31 July 2006). "It's Official: "Batman 2" Gets A Title". DarkHorizons. Retrieved 9 March 2007.

- ↑ "The Dark Knight: The Original Feature". Empire. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ↑ "The 50 Best Movies of the Decade (2000–2009)". Paste. 3 November 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- ↑ "Review of the Decade – Year-By-Year: Empire's Films Of The Decade". Empire. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ↑ Manohla Dargis (18 July 2008). "The Dark Knight-Showdown in Gotham Town". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ↑ Roger Ebert (16 July 2008). "The Dark Knight". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ↑ "Kevin Smith Reviews The Dark Knight; New Zack and Miri Photo". Slashfilm. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ Brooks Barnes (28 July 2008). "Dark Knight Wins Again at Box Office". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ↑ "The Dark Knight (2008)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ↑ "Warner Bros and Christopher Nolan Break New Ground with The Dark Knight". About. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ "The Oscars 2009". BBC News.

- ↑ Fleming, Michael (11 February 2009). "Nolan tackles 'Inception' for WB". Variety. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- ↑ Miller, Jenni (24 June 2010). "Will 'Inception' Be Too Smart for Audiences?". Moviefone. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ↑ "Warner Bros. Keeping INCEPTION in Oscar-voters' Minds with "New" Behind-the-Scenes Featurette". Collider.com. 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ Roeper, Richard. "Inception Review". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- ↑ Kermode, Mark (24 December 2010). Kermode Uncut: My Top Five Films of the Year. BBC. Event occurs at 5:05. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ↑ Schuker, Lauren (16 July 2010). "Studios Root for 'Inception'". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ↑ "Inception (2010)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ↑ "2011 Academy Awards Nominations and Winners".

- ↑ "These Amazing Shadows Are Unveiled at Sundance 2011". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ↑ Mintzer, Jordan. "Side by Side: Berlin Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ↑ Bettinger, Brendan (10 March 2010). "Christopher Nolan Speaks! Updates on Dark Knight Sequel and Superman Man of Steel". Collider.com. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ↑ Boucher, Geoff (27 October 2010). "Christopher Nolan reveals title of third Batman film and that 'it won't be the Riddler'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ↑ ""The Dark Knight Rises": Christopher Nolan's evil masterpiece". Salon. 18 July 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ↑ Lemire, Christy (16 July 2012). "Batman Review: Is 'The Dark Knight Rises' An Epic Letdown?". Associated Press. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ Box Office Mojo: Index Christopher Nolan; retrieved 13 September 2012

- ↑ McClintock, Pamela (2 September 2012). "Box Office Milestone: 'Dark Knight Rises' Crosses $1 Billion Worldwide". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ↑ Brown, Jennifer. "12 shot dead, 58 wounded in Aurora movie theater during Batman premier". Denver Post. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan on Theater Shooting: 'I Would Like to Express Our Profound Sorrow'". Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- 1 2 "Christopher Nolan on Batman and Superman". Superhero Hype!. 4 June 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ Outlaw, Kofi. "Chris Nolan Talks Superman Reboot & Batman 3". screenrant.com. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ↑ Finke, Nikki; Fleming, Mike (9 February 2010). "It's A Bird! It's A Plane! It's Chris Nolan! He'll Mentor Superman 3.0 And Prep 3rd Batman". Deadline. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ↑ Schuker, Lauren A. E. (22 August 2008). "Warner Bets on Fewer, Bigger Movies". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ↑ Itzkoff, Dave (22 May 2013). "Alien, Yet Familiar". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ↑ "Man of Steel Reviews – Metacritic". Metacritic. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ "Man of Steel score – Critics' Choice". Broadcast Film Critics Association. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ↑ Kit, Borys (13 June 2012). "Christopher Nolan to Exec Produce Wally Pfister's Directorial Debut". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ↑ Zeitchik, Steven (10 January 2014). "'Transcendence' into directing for cinematographer Wally Pfister". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Staff (24 April 2013). "Warner Bros Dates Adam Sandler-Drew Barrymore Pic 'Blended', Shifts 'Transcendence'". Deadline. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ↑ "Transcendence (2014)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan's 'Interstellar': 'Dark Knight Rises' Director Lines Up Next Project". Huffington Post. 9 January 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ↑ Jagernauth, Kevin (10 January 2013). "Christopher Nolan's Merging An Original Idea With Jonah Nolan's Old Screenplay For 'Interstellar'". The Playlist. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ↑ Christopher Nolan's 'Interstellar' To Be Paramount–Warner Bros Co-Production And Joint Distribution

- ↑ "Interstellar Reviews". metacritic.com. Metacritic. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ "Interstellar (2014)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ "Off to the Stars, With Grief, Dread and Regret". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ "Interstellar (United States/United Kingdom, 2014)". Reelviews. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ↑ "Space station film school: How astronauts shot this glorious IMAX movie". CNET. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ↑ "Interstellar 'should be shown in school lessons'". BBC. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ↑ Kilday, Gregg (9 December 2014). "AFI List of Top 10 Films Expands to Include 11". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ↑ "Oscars 2015: See the Full List of Nominees". Time. 15 January 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ↑ "Paramount Teams with Google Play for ‘Interstellar’ Time-Capsule Promo (Video)". Variety. 20 November 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "Google hits Play on 'Interstellar' video time capsule". USA Today. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ McNary, Dave (19 February 2015). "Christopher Nolan’s Syncopy Teaming With Zeitgeist on Blu-ray Releases (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ↑ "Why 'The Quay Brothers in 35mm' is One of Christopher Nolan's Greatest Accomplishments". Indiewire. 20 August 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan's next movie is a documentary short". Entertainment Weekly. 27 July 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan Joins Film Foundation Board". Deadline. 22 April 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan Rallies the Troops to Save Celluloid Film". Variety. 11 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ↑ "Tarantino and Nolan share a Kodak moment as studios fund film processing". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ↑ "DGA Congratulates Martin Scorsese and Christopher Nolan on Appointments to National Film Preservation Board". The Directors Guild of America. 7 May 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ "Charles Roven: Ben Affleck "Was the First Guy We Went to" for Batman Role". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ Nemiroff, Perri (10 November 2014). "Christopher Nolan Discusses Ben Affleck’s Casting in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice". Collider. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ "Early 'Batman v Superman' Reviews: What the Critics Are Saying". Variety. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ "Venice Film Review: Cinema Futures". Variety. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ↑ Nolan, Christopher (8 July 2017). "Spitfires, flotillas of boats, rough seas and 1,000 extras: Christopher Nolan on the making of Dunkirk, his most challenging film to date". The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ "WWII on a Grand Scale". DGA. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan Inspired by Robert Bresson and Silent Films for 'Dunkirk,' Which Has "Little Dialogue"". The Film Stage. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan et ses collaborateurs révèlent 7 infos sur Dunkerque". Première. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ McNary, Dave (11 March 2016). "Harry Styles, Fionn Whitehead to Star in Christopher Nolan WW2 Action-Thriller ‘Dunkirk’". Variety. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ↑ "'Dunkirk': What the Critics Are Saying". The Hollywood Reporter. 17 July 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Dunkirk Reviews – Metacritic". Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ↑ "How Dunkirk, Summer’s Boldest Box-Office Gamble, Paid Off". Vanity Fair'. 24 July 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ "Review: 'Dunkirk' Is a Tour de Force War Movie, Both Sweeping and Intimate". The New York Times. 20 July 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ↑ "Christopher Nolan, an Auteur in Contemporary Cinema?". The Huffington Post. 27 July 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ↑ "Time, Memory & Identity: The Films of Christopher Nolan". Grin - Master's Thesis written by Stuart Joy. 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ↑ "The Reason Christopher Nolan Films Look Like Christopher Nolan Films". The Atlantic. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Bevan, Joseph (18 July 2012). "Christopher Nolan: escape artist". BFI. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- 1 2 "Analysis: The Films of Christopher Nolan". Left Field Cinema. 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2013.