Chloral hydrate

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2,2,2-Trichloroethane-1,1-diol | |

| Other names

Trichloroacetaldehyde monohydrate Tradenames: Aquachloral, Novo-Chlorhydrate, Somnos, Noctec, Somnote | |

| Identifiers | |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.562 |

| EC Number | 206-117-5 |

| KEGG | |

| PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number | FM875000 |

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C2H3Cl3O2 | |

| Molar mass | 165.39 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless solid |

| Odor | Aromatic, slightly acrid |

| Density | 1.9081 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 57 °C (135 °F; 330 K) |

| Boiling point | 98 °C (208 °F; 371 K) |

| 660g/100 ml[1] | |

| Solubility | Very soluble in benzene, ethyl ether, ethanol |

| log P | 0.99 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 9.66, 11.0[2] |

| Structure | |

| Monoclinic | |

| Pharmacology | |

| N05CC01 (WHO) | |

| |

| Oral syrup, rectal suppository | |

| Pharmacokinetics: | |

| Well absorbed | |

| Hepatic and renal (converted to trichloroethanol) | |

| 8–10 hours | |

| Bile, feces, urine (various metabolites not unchanged) | |

| Legal status |

|

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | External MSDS |

| EU classification (DSD) (outdated) |

Harmful (Xn) |

| R-phrases (outdated) | R22 R36 R37 R38 |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

| LD50 (median dose) |

1100 mg/kg (mouse, oral) |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Chloral, chlorobutanol |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

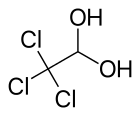

Chloral hydrate is a geminal diol with the formula C2H3Cl3O2. It is a colorless solid. It has limited use as a sedative and hypnotic pharmaceutical drug. It is also a useful laboratory chemical reagent and precursor. It is derived from chloral (trichloroacetaldehyde) by the addition of one equivalent of water.

It was discovered through the chlorination (halogenation) of ethanol in 1832 by Justus von Liebig in Gießen.[3][4] Its sedative properties were first published in 1869 and subsequently, because of its easy synthesis, its use was widespread.[5] It was widely used recreationally and misprescribed in the late 19th century. Chloral hydrate is soluble in both water and ethanol, readily forming concentrated solutions. A solution of chloral hydrate in ethanol called "knockout drops" was used to prepare a Mickey Finn.[6] More reputable uses of chloral hydrate include its use as a clearing agent for chitin and fibers and as a key ingredient in Hoyer's mounting medium, which is used to prepare permanent or semi-permanent microscope slides of small organisms, histological sections, and chromosome squashes. Because of its status as a regulated substance, chloral hydrate can be difficult to obtain. This has led to chloral hydrate being replaced by alternative reagents[7][8] in microscopy procedures.

It is, together with chloroform, a minor side-product of the chlorination of water when organic residues such as humic acids are present. It has been detected in drinking water at concentrations of up to 100 micrograms per litre (µg/L) but concentrations are normally found to be below 10 µg/L. Levels are generally found to be higher in surface water than in ground water.[9]

Chloral hydrate has not been approved by the FDA in the United States or the EMA in the European Union for any medical indication and is on the list of unapproved drugs that are still prescribed by clinicians.[10] Usage of the drug as a sedative or hypnotic may carry some risk given the lack of clinical trials.

Uses

Hypnotic

Chloral hydrate is used for the short-term treatment of insomnia and as a sedative before minor medical or dental treatment. It was largely displaced in the mid-20th century by barbiturates[11] and subsequently by benzodiazepines. It was also formerly used in veterinary medicine as a general anesthetic. It is also still used as a sedative prior to EEG procedures, as it is one of the few available sedatives that does not suppress epileptiform discharges.[12]

In therapeutic doses for insomnia, chloral hydrate is effective within 20 to 60 minutes.[13] In humans it is metabolized within 7 hours into trichloroethanol and trichloroethanol glucuronide by erythrocytes and plasma esterases and into trichloroacetic acid in 4 to 5 days.[14] It has a very narrow therapeutic window making this drug difficult to use. Higher doses can depress respiration and blood pressure.

Building block in organic synthesis

Chloral hydrate is a starting point for the synthesis of other organic compounds. It is the starting material for the production of chloral, which is produced by the distillation of a mixture of chloral hydrate and sulfuric acid, which serves as the desiccant.

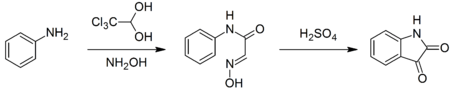

Notably, it is used to synthesize isatin. In this synthesis, chloral hydrate reacts with aniline and hydroxylamine to give a condensation product which cyclicizes in sulfuric acid to give the target compound:[15]

Safety

Chloral hydrate was routinely administered to people on the gram scale. Prolonged exposure to the vapors is unhealthy however, with a LD50 for 4-hour exposure of 440 mg/m3. Long-term use of chloral hydrate is associated with a rapid development of tolerance to its effects and possible addiction as well as adverse effects including rashes, gastric discomfort and severe kidney, heart, and liver failure.[16]

Acute overdosage is often characterized by nausea, vomiting, confusion, convulsions, slow and irregular breathing, cardiac arrhythmia, and coma. The plasma, serum or blood concentrations of chloral hydrate and/or trichloroethanol, its major active metabolite, may be measured to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to aid in the medicolegal investigation of fatalities. Accidental overdosage of young children undergoing simple dental or surgical procedures has occurred. Hemodialysis has been used successfully to accelerate clearance of the drug in poisoning victims.[17]

Production

Chloral hydrate is produced from chlorine and ethanol in acidic solution. In basic conditions the haloform reaction takes place and chloral hydrate is decomposed by hydrolysis to form chloroform.[18]

- 4 Cl2 + C2H5OH + H2O → Cl3CCH(OH)2 + 5 HCl

Pharmacodynamics

Chloral hydrate is metabolized in vivo[19] to trichloroethanol, which is responsible for its physiological and psychological effects.[20]

The metabolite of chloral hydrate exerts its pharmacological properties via enhancing the GABA receptor complex[21] and therefore is similar in action to benzodiazepines, nonbenzodiazepines and barbiturates. It can be moderately addictive, as chronic use is known to cause dependency and withdrawal symptoms. The chemical can potentiate various anticoagulants and is weakly mutagenic in vitro and in vivo.

Legal status

In the United States, chloral hydrate is illegal without a prescription and is a schedule IV controlled substance. Its properties have sometimes led to its use as a date rape drug.[22][23] Chloral hydrate is still available in the United States, though it is relatively uncommon and not often kept in the inventory of major pharmacies. It has largely been abandoned for the treatment of insomnia in favor of newer drugs such as the Z-drugs family, which includes zolpidem, zaleplon, zopiclone and eszopiclone. A small number of medical practitioners continue to prescribe it to treat insomnia when all other more modern medications have failed. In the United States, it is commonly supplied in syrup form in a 500 mg/5mL concentration. It is also supplied in suppository form, though the use of this method of administration is extremely rare.

It is not controlled in Canada except that a prescription is required to purchase the pharmaceutical forms. Possession without a prescription is not illegal and industrial trade is not regulated.

The United Kingdom does not consider chloral hydrate to be a controlled substance.

Chloral hydrate is a prescription-only-medicine (POM) in the Netherlands, but possession without a valid prescription will result only in the seizure of the drug, not prosecution. Production, sale and distribution are however punishable by law. It is not listed under the Dutch Opium Law, but when the intent is human consumption, it is covered by the Geneesmiddelenwet (Medicine Act).

Hoyer's mounting medium

Chloral hydrate is also an ingredient used for Hoyer's solution, a mounting medium for microscopic observation of diverse organisms such as bryophytes, ferns, seeds, and small arthropods (especially mites). Other ingredients may include gum arabic and glycerol . An advantage of this medium include a high refraction index and clearing (macerating) properties of the small specimens (especially advantageous if specimens require observation with differential interference contrast microscopy).

History

Chloral hydrate was first synthesized by the chemist Justus von Liebig in 1832 at the University of Giessen.[24] Through experimentation physiologist Claude Bernard clarified that the chloral hydrate was hypnotic as opposed to an analgesic.[25] It was the first of a long line of sedatives, most notably the barbiturates, manufactured and marketed by the German pharmaceutical industry.[24] Historically, chloral hydrate was utilized primarily as a psychiatric medication. In 1869, German physician and pharmacologist Oscar Liebreich began to promote its use to calm anxiety, especially when it caused insomnia.[26][25] Chloral hydrate had certain advantages over morphine for this application, as it worked quickly without injection and had a consistent strength. It achieved wide use in both asylums and the homes of those socially refined enough to avoid asylums. Upper and middle class women, well-represented in the latter category, were particularly susceptible to chloral hydrate addiction. After the 1904 invention of barbital, the first of the barbiturate family, chloral hydrate began to disappear from use among those with means.[24] It remained common in asylums and hospitals until the Second World War as it was quite cheap. Chloral hydrate had some other important advantages that kept it in use for five decades despite the existence of more advanced barbiturates. It was the safest available sedative until the middle of the twentieth century, and thus was thus particularly favored for children.[25] It also left patients much more refreshed after a deep sleep than more recently invented sedatives. Its frequency of use made it an early and regular feature in the Merck Manual.[27]

Chloral hydrate also was also a significant object of study in various early pharmacological experiments. In 1875, Claude Bernard tried to tell if chloral hydrate exerted its action through a metabolic conversion to chloroform. This was not only the first attempt to determine whether different drugs were converted to the same metabolite in the body but also the first to measure the concentration of a particular pharmaceutical in the blood. The results were inconclusive.[28] In 1899 and 1901 Hans Horst Meyer and Ernest Overton respectively made the major discovery that the general anaesthetic action of a drug was strongly correlated to its lipid solubility. But, chloral hydrate was quite polar but nonetheless a potent hypnotic. Overton was unable to explain this mystery. Thus, chloral hydrate remained one of the major and persistent exceptions to this breakthrough discovery in pharmacology. This anomaly was eventually resolved in 1948, when Claude Bernard's experiment was repeated. While chloral hydrate was converted to a different metabolite than chloroform, it was found that was converted into the more lipophilic molecule 2,2,2-Trichloroethanol. This metabolite fit much better with the Meyer-Overton correlation than chloral had. Prior to this, it had not been demonstrated that general anesthetics could undergo chemical changes to exert their action in the body.[29]

Finally, chloral hydrate was also the first hypnotic to be used intravenously as a general anesthetic. In 1871, Pierre-Cyprien Oré began experiments on animals, followed by humans. While a state of general anesthesia could be achieved, the technique never caught on because its administration was more complex and less safe than the oral administration of chloral hydrate, and less safe for intravenous use than later general anesthetics were found to be.[30]

Notable uses

- The Jonestown mass suicides in 1978, involved the communal drinking of Flavor Aid poisoned with Valium, chloral hydrate, cyanide, and Phenergan

- Richard Realf (1832–1878) killed himself with a combination of chloral hydrate and laudanum.[31]

- Anna Nicole Smith (1967–2007) who died of an accidental[32] combination of chloral hydrate with four benzodiazepines and several other drugs, as announced by forensic pathologist Dr. Joshua Perper on 26 March 2007. Chloral hydrate was the major factor, but it was unclear if any of these drugs would have been sufficient by itself to cause her death.[33]

- Hank Williams (1923–1953) came under the spell of a man calling himself "Doctor" Toby Marshall (actually a paroled forger), who often supplied him with prescriptions and injections of chloral hydrate, which Marshall claimed was a pain reliever, to deal with the pain from Williams' lifelong severe back problems.[34]

- André Gide (1869–1951) was given chloral hydrate as a boy for sleep problems by a physician named Lizart. Gide states in his autobiography, If It Die... that "all my later weaknesses of will or memory I attribute to him."[35]

- Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) regularly used chloral hydrate in the years leading up to his nervous breakdown, according to Lou Salome and other associates. Whether the drug contributed to his insanity is a point of controversy.[36]

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) became addicted to its use in conjunction with his growing alcoholism. It contributed to his increasing paralysis, psychotic behaviour and ultimately his death.

- John Boyle O'Reilly (1844–1890) overdosed on his wife's sleeping medication which contained chloral hydrate, which resulted in his death from heart failure the next morning.

- Oliver Sacks (1933-2015) abused chloral hydrate in 1965 as a depressed insomniac. He found himself taking fifteen times the usual dose of chloral hydrate every night before he eventually ran out, causing violent withdrawal symptoms.[37]

- Marilyn Monroe (1926–1962) died from an overdose of chloral hydrate and pentobarbital (Nembutal).[38][39]

- The Family Murders

See also

References

- ↑ "Chemical Book: Chloral hydrate". Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ↑ Gawron O, Draus F (1958). "Kinetic Evidence for Reaction of Chloralate Ion with p-Nitrophenyl Acetate in Aqueous Solution". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80 (20): 5392–5394. doi:10.1021/ja01553a018.

- ↑ Justus Liebig (1832). "Ueber die Zersetzung des Alkohols durch Chlor" [On the degradation of alcohol by chlorine]. Annalen der Pharmacie. 1 (1): 31–32. doi:10.1002/jlac.18320010109.

- ↑ Justus Liebig (1832). "Ueber die Verbindungen, welche durch die Einwirkung des Chlors auf Alkohol, Aether, ölbildendes Gas und Essiggeist entstehen" [On compounds that arise by the reaction of chlorine with alcohol, oil-forming gas [i.e., ethane], and acetone]. Annalen der Pharmacie. 1 (2): 182–230. doi:10.1002/jlac.18320010203.

- ↑ Liebreich, Oskar (1869). Das Chloralhydrat : ein neues Hypnoticum und Anaestheticum und dessen Anwendung in der Medicin ; eine Arzneimittel-Untersuchung. Berlin: Müller.

- ↑ http://www.justice.gov/dea/concern/chloral_hydrate.html Archived 11 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "An Improved Clearing and Mounting Solution to Replace Chloral Hydrate in Microscopic Applications". Applications in Plant Sciences. 1 (5): 1300016. doi:10.3732/apps.1300016.

- ↑ Li, J; Pan, L; Naman, CB; Deng, Y; Chai, H; Keller, WJ; Kinghorn, AD. "Pyrrole Alkaloids with Potential Cancer Chemopreventive Activity Isolated from a Goji Berry-Contaminated Commercial Sample of African Mango". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 62 (22): 5054–5060. PMC 4047925

. PMID 24792835. doi:10.1021/jf500802x.

. PMID 24792835. doi:10.1021/jf500802x. - ↑ "Summary statement - 12.20 Chloral hydrate (trichloroacetaldehyde)" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ↑ Michelle Meadows (January–February 2007). "The FDA Takes Action Against Unapproved Drugs" (PDF). FDA Consumer magazine.

- ↑ Tariq, Syed H.; Pulisetty, Shailaja (2008). "Pharmacotherapy for Insomnia". Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 24 (1): 93–105. PMID 18035234. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2007.08.009.

- ↑ http://jcc.kau.edu.sa/Files/140/Researches/11822_Chloral.pdf

- ↑ Gauillard J, Cheref S, Vacherontrystram MN, Martin JC (May–Jun 2002). "Chloral hydrate: a hypnotic best forgotten?". Encephale. 28 (3 Pt 1): 200–204. PMID 12091779.

- ↑ Beland, Frederick A. "NTP Technical Report on the Toxicity and Metabolism Studies of Chloral Hydrate" (PDF). Toxicity Report Series Number 59. National Toxicology Program. p. 10. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ↑ C. S. Marvel and G. S. Hiers (1941). "Isatin". Org. Synth.; Coll. Vol., 1, p. 327

- ↑ Gelder M, Mayou R, Geddes J (2005). Psychiatry (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford. p. 238.

- ↑ R. Baselt (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 259–261.

- ↑ Takahashi, Yasuo; Onodera, Sukeo; Morita, Masatoshi; Terao, Yoshiyasu (2003). "A Problem in the Determination of Trihalomethane by Headspace-Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry" (PDF). Journal of Health Science. 49 (1): 3. doi:10.1248/jhs.49.1.

- ↑ Trichloroethanol

- ↑ Reinhard Jira, Erwin Kopp, Blaine C. McKusick, Gerhard Röderer, Axel Bosch and Gerald Fleischmann "Chloroacetaldehydes" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2007, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a06_527.pub2

- ↑ Lu, J; Greco, MA (2006). "Sleep circuitry and the hypnotic mechanism of GABAA drugs". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2 (2): S19–26. PMID 17557503.

- ↑ Canadian Public Health Association (December 2004). "Rising Incidence of Hospital-reported Drug-facilitated Sexual Assault in a Large Urban Community in Canada: Retrospective Population-based Study". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 95 (6): 441.

- ↑ New York Daily News, 10/25/2008

- 1 2 3 Edward., Shorter, (1998-01-01). A history of psychiatry : from the era of the asylum to the age of Prozac. Wiley. ISBN 0471245313. OCLC 60169541.

- 1 2 3 Thomas., Dormandy, (2006-01-01). The worst of evils : the fight against pain. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300113226. OCLC 878623979.

- ↑ Edward., Shorter, (2009-01-01). Before Prozac : the troubled history of mood disorders in psychiatry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195368741. OCLC 299368559.

- ↑ Cuadrado, Fernando F.; Alston, Theodore A. (2016-10-01). "Book Review". Journal of Anesthesia History. 2 (4): 153–155. ISSN 2352-4529. doi:10.1016/j.janh.2016.01.004.

- ↑ Alston, Theodore A. (2016-07-01). "Noteworthy Chemistry of Chloroform". Journal of Anesthesia History. 2 (3): 85–88. ISSN 2352-4529. doi:10.1016/j.janh.2016.04.008.

- ↑ Krasowski, Matthew D. "Contradicting a Unitary Theory of General Anesthetic Action: a History of Three Compounds from 1901 to 2001". Bulletin of Anesthesia History. 21 (3): 1–24. doi:10.1016/s1522-8649(03)50031-2.

- ↑ Roberts, Matthew; Jagdish, S. (2016-01-01). "A History of Intravenous Anesthesia in War (1656-1988)". Journal of Anesthesia History. 2 (1): 13–21. ISSN 2352-4529. doi:10.1016/j.janh.2015.10.007.

- ↑ Rathmell, George W. (2002). A Passport to Hell: The Mystery of Richard Realf. Lincoln, Nebraska: Authors Choice Press. pp. ix, 134. ISBN 0-595-21251-4. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ↑ Anna Nicole Smith Autopsy Report. XI. Manner of death. A. The Exclusion of Homicide Archived 13 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. The Smoking Gun

- ↑ Anna Nicole Smith Autopsy Released. Coroner: Ex-Playmate died from accidental sedative overdose The Smoking Gun

- ↑ Hank Williams summary Book Rags

- ↑ Gide, André and Dorothy Bussey (trans). If It Die...An Autobiography. New York: Vintage International, 2001. p105

- ↑ Noumenautics, ch. VI

- ↑ Sacks, Oliver. "Altered States". The New Yorker, 27 Aug 2012. The New Yorker. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ↑ Banner, Lois (2012). Marilyn: The Passion and the Paradox. Bloomsbury. pp. 411–412. ISBN 978-1-40883-133-5.

- ↑ Spoto, Donald (2001). Marilyn Monroe: The Biography. Cooper Square Press. pp. 580–583. ISBN 0-8154-1183-9.

External links

![]() Media related to Chloral hydrate at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chloral hydrate at Wikimedia Commons