Chinook wind

Chinook winds /ʃɪˈnʊk/, or simply chinooks, are föhn winds[1] in the interior West of North America, where the Canadian Prairies and Great Plains meet various mountain ranges, although the original usage is in reference to wet, warm coastal winds in the Pacific Northwest.[2]

Chinook is claimed by popular folk-etymology to mean "ice-eater", but it is really the name of the people in the region where the usage was first derived. The reference to a wind or weather system, simply "a Chinook", originally meant a warming wind from the ocean into the interior regions of the Pacific Northwest of the USA (the Chinook people lived near the ocean, along the lower Columbia River). A strong Chinook can make snow one foot (30 cm) deep almost vanish in one day. The snow partly melts and partly evaporates in the dry wind. Chinook winds have been observed to raise winter temperature, often from below −20 °C (−4 °F) to as high as 10–20 °C (50–68 °F) for a few hours or days, then temperatures plummet to their base levels. The greatest recorded temperature change in 24 hours was caused by Chinook winds on January 15, 1972, in Loma, Montana; the temperature rose from −48 to 9 °C (−54 to 49 °F).[3]

In Canada

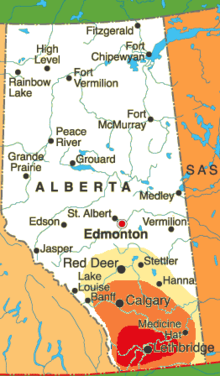

Chinooks are most prevalent over southern Alberta in Canada, especially in a belt from Pincher Creek and Crowsnest Pass through Lethbridge, which get 30 to 35 Chinook days per year on average. Chinooks become less frequent further south in the United States, and are not as common north of Red Deer, but they can and do occur annually as far north as High Level in northwestern Alberta and Fort St. John in northeastern British Columbia, and as far south as Albuquerque, New Mexico.

In southwestern Alberta, Chinook winds can gust in excess of hurricane force 120 km/h (75 mph). On November 19, 1962, an especially powerful Chinook in Lethbridge gusted to 171 km/h (106 mph).

In Pincher Creek, the temperature rose by 41 °C (74 °F), from −19 to 22 °C (−2 to 72 °F), in one hour in 1962.[4] Trains have been known to be derailed by Chinook winds. During the winter, driving can be treacherous, as the wind blows snow across roadways, sometimes causing roads to vanish and snowdrifts to pile up higher than a metre. Empty semitrailer trucks driving along Highway 3 and other routes in southern Alberta have been blown over by the high gusts of wind caused by Chinooks.

Calgary, Alberta also gets many Chinooks – the Bow Valley in the Canadian Rockies west of the city acts as a natural wind tunnel, funneling the chinook winds.

On 27 February 1992, Claresholm, Alberta a small city just south of Calgary; recorded a temperature of 24 °C (75 °F)[5] again the next day 21 °C (70 °F) was recorded.[5] These are some Canada's highest February temperatures.

Versus the Arctic air mass

The Chinook can seem to do battle with the Arctic air mass at times. It is not unheard of for people in Lethbridge to complain of −20 °C (−4 °F) temperatures while those in Cardston, just 77 km (48 mi) down the road, enjoy 10 °C (50 °F) temperatures. This clash of temperatures can remain stationary, or move back and forth, in the latter case causing such fluctuations as a warm morning, a bitterly cold afternoon, and a warm evening. A curtain of fog often accompanies the clash between warm to the west and cold to the east.

Chinook arch

One of its most striking features is the Chinook arch, which is a band of stationary stratus clouds caused by air rippling over the mountains due to orographic lifting. To those unfamiliar with it, the Chinook arch may look like a threatening storm cloud at times. However, they rarely produce rain or snow. They can also create stunning sunrises and sunsets.

The stunning colours seen in the Chinook arch are quite common. Typically, the colours will change throughout the day, starting with yellow, orange, red and pink shades in the morning as the sun comes up, grey shades at midday changing to pink/red colours, and then orange/yellow hues just before the sun sets.

- Chinook arch over Calgary, January 6, 2003

The extreme colours of a Chinook arch

The extreme colours of a Chinook arch Chinook arch in Calgary, Alberta, November 19, 2005

Chinook arch in Calgary, Alberta, November 19, 2005- Chinook arch over Calgary, March 2007

Chinook arch over Kelowna, BC Canada, October 2, 2007

Chinook arch over Kelowna, BC Canada, October 2, 2007

Cause of occurrence

The Chinook is a föhn wind, a rain shadow wind which results from the subsequent adiabatic warming of air which has dropped most of its moisture on windward slopes (orographic lift). As a consequence of the different adiabatic rates of moist and dry air, the air on the leeward slopes becomes warmer than equivalent elevations on the windward slopes.

As moist winds from the Pacific (also called Chinooks) are forced to rise over the mountains, the moisture in the air is condensed and falls out as precipitation, while the air cools at the moist adiabatic rate of 5 °C/1000 m (3.5 °F/1000 ft). The dried air then descends on the leeward side of the mountains, warming at the dry adiabatic rate of 10 °C/1000 m (5.5 °F/1000 ft).[6]

The turbulence of the high winds also can prevent the usual nocturnal temperature inversion from forming on the lee side of the slope, allowing night-time temperatures to remain elevated.[6]

Quite often, when the Pacific Northwest coast is being drenched by rain, the windward side of the Rockies is being hammered by snow (as the air loses its moisture), and the leeward side of the Rockies in Alberta is basking in a föhn Chinook. The three different weather conditions are all caused by the same flow of air, hence the confusion over the use of the name "Chinook wind".

Two common cloud patterns seen during this time are a chinook arch overhead, and a bank of clouds (also referred to as a cloud wall) obscuring the mountains to the west. It appears to be an approaching storm, but does not advance any further east.

The Manyberries Chinook

Often, a Chinook is preceded by a "Manyberries Chinook" during the end of a cold spell. This southeast wind (named for the small village Manyberries, now a hamlet, in southeastern Alberta, from where the wind seems to originate) can be fairly strong and cause bitter windchill and blowing snow. The wind will eventually swing around to the southwest and the temperature rises sharply as the real Chinook arrives.

In the Pacific Northwest

The term Chinook wind is also used in British Columbia, and is the original usage, being rooted in the lore of coastal tribes and brought to Alberta by the fur-traders.[2][7] Such winds are extremely wet and warm and arrive off the western coast of North America from the southwest. The winds are also known as the pineapple express, since they are of tropical origin, roughly from the area of the Pacific near Hawaii. The air associated with a west coast Chinook is stable; this minimizes wind gusts and often keeps winds light in sheltered areas. In exposed areas, fresh gales are frequent during a Chinook, but strong gale- or storm-force winds are uncommon (most of the region's stormy winds come when a fast 'westerly' jet stream lets air masses from temperate and subarctic latitudes clash).

When a Chinook comes in when an Arctic air mass is holding steady over the coast, the tropical dampness brought in suddenly cools, penetrating the frozen air and coming down in volumes of powder snow, sometimes to sea level. Snowfalls and the cold spells that spawned them only last a few days during a Chinook; as the warm Chinooks blow from the southwest, they push back east the cold Arctic air. The snow melts quickly and is gone within a week.

The effects on the Interior of British Columbia when a Chinook is in effect are the reverse. In a rainy spell, most of the heavy moisture will be soaked out by the ramparts of mountains before the air mass reaches the Fraser Canyon and the Thompson River-Okanagan area. The effects are similar to those of an Alberta Chinook, though not to the same extreme, in part because the Okanagan is relatively warmer than the Prairies, and because of the additional number of precipitation-catching mountain ranges between Kelowna and Calgary. When the Chinook brings snow to the coast during a period of coastal cold, bright but chilly weather in the interior will give way to a slushy melting of snow, more due to the warm spell than because of rain.

The word is in common usage among local fishermen and people in communities along the British Columbia Coast and coastal Washington. The term is also used in the Puget Sound area of Washington. "Chinook" is not pronounced as it is east of the Cascades – shinook – but is in the original coastal pronunciation tshinook.[8]

The resulting outflow wind is more or less the opposite of British Columbia/Pacific Northwest Chinook. These are called a squamish in certain areas, rooted in the direction of such winds coming down out of Howe Sound, home to the Squamish people, and in Alaska are called a williwaw. They consist of cold airstreams from the continental air mass pouring out of the interior plateau via certain river valleys and canyons penetrating the Coast Mountains towards the coast.

Pronunciation in the Pacific Northwest

In British Columbia and other parts of the Pacific Northwest, the word Chinook was once often pronounced /tʃɪnʊk/ chinuuk. Currently, the common pronunciation throughout most of the Pacific Northwest, Alberta, and the rest of Canada, is /ʃɪnʊk/ shinuuk, as in French. This difference may be because it was the Métis employees of the Hudson's Bay Company, who were familiar with the Chinook people and country, brought the name east of the Cascades and Rockies, along with their own ethnified pronunciation. Early records are clear that tshinook was the original pronunciation, before the word's transmission east of the Rockies.[8]

First nations myth from British Columbia

Native legend of the Lil'wat subgroup of the St'at'imc tells of a girl named Chinook-Wind, who married Glacier, and moved to his country, which was in the area of today's Birkenhead River.[9][10] She pined for her warm sea-home in the southwest, and sent a message to her people. They came to her in a vision in the form of snowflakes, and told her they were coming to get her. They came in great number and quarrelled with Glacier over her, but they overwhelmed him and she went home with them in the end.

While on the one hand this tale tells a tribal family-relations story, and family/tribal history as well, it also seems to be a parable of a typical weather pattern of a southwesterly wind at first bringing snow, then rain, and also of the melting of a glacier, namely the Place Glacier near Gates Lake at Birken. Thus, it also tells of a migration of people to the area, (or a war, depending on how the details of the legend might be read, with Chinook-Wind taking the part of Helen in a First Nations parallel to the Trojan War).

Gardening

The frequent midwinter thaws in Great Plains Chinook country are more of a bane than a blessing to gardeners. Plants can be visibly brought out of dormancy by persistent Chinook winds, or have their hardiness reduced even if they appear to be remaining dormant. In either case, they become vulnerable to later cold waves. Many plants which do well at Winnipeg (where constant cold maintains dormancy all winter) are difficult to grow in the Alberta Chinook belt; examples include basswood, some apple, raspberry and Saskatoon varieties, and Amur maples. Trees in the Chinook-affected areas of Alberta are known to be small, with much less growth than trees in areas not affected by Chinooks. This is once again caused by the 'off-and-on' dormancy throughout winter.

Health

Chinook winds are said to sometimes cause a sharp increase in the number of migraine headaches suffered by the locals. At least one study conducted by the department of clinical neurosciences at the University of Calgary supports that belief.[11] They are popularly believed to increase irritability and sleeplessness. In mid-winter over major centres such as Calgary, Chinooks can often override cold air in the city, trapping the pollutants in the cold air and causing inversion smog. At such times, it is possible for it to be cold at street level and much warmer at the tops of the skyscrapers and in higher terrain. In 1983, on the 45th floor [about 145 m (460 ft) above the street] of the Petro-Canada Center, carpenters worked shirtless in 12 °C, windy conditions (temperature reported to them by overhead crane operator), but were chagrined to find out the street temperature was still −20 °C as they left work at 3:30 that afternoon.

Folklore

Three especially famous Chinook folk tales are probably known in some form by most people in southern Alberta from childhood stories.

- A man rode his horse to church, only to find just the steeple sticking out of the snow. So, he tied his horse to the steeple with the other horses, and went down the snow tunnel to attend services. When everybody emerged from the church, they found a Chinook had melted all of the snow, and their horses were now all dangling from the church steeple.

- A man was riding his sleigh to town when a Chinook overcame him. He kept pace with the wind, and while the horses were running belly-deep in snow, the sleigh rails were running in mud up to the buckboard. The cow tied behind was kicking up dust.

- A man and his wife were out during a Chinook. The wife was heavily dressed and the man was wearing summer clothes. When the couple had returned home, the man had frostbite, and the woman had a heatstroke.

- A man was riding his horse from Pincher Creek to Ft MacLeod during a chinook. The horse lifted its tail to relieve itself. The bit blew out of its mouth.

Records

Loma, Montana, boasts having the most extreme recorded temperature change in a 24-hour period. On January 15, 1972, the temperature rose from −54 to 49 °F (−48 to 9 °C), a 103 °F (58 °C) change in temperature, a dramatic example of the regional Chinook wind in action.

The Black Hills of South Dakota are home to the world's fastest recorded rise in temperature. On January 22, 1943, at about 7:30 am MST, the temperature in Spearfish, South Dakota, was −4 °F (−20 °C). The chinook kicked in, and two minutes later, the temperature was 45 °F (7 °C). The 49 °F (27 °C) rise set a world record, yet to be exceeded. By 9:00 am, the temperature had risen to 54 °F (12 °C). Suddenly, the Chinook died down and the temperature tumbled back to −4 °F (−20 °C). The 58 °F (32 °C) drop took only 27 minutes.[12][13]

The aforementioned 107 mph (172 km/h) wind in Alberta and other local wind records west of the 100th meridian on the Great Plains of the United States and Canada, as well as instances of the record high and low temperature for a given day of the year being set on the same date, are largely the result of these winds.

On rare occasions, Chinook winds generated on the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains have reached as far east as Wisconsin.[14]

Chinooks and föhn winds in the inland United States

Chinooks are generally called föhn winds by meteorologists and climatologists, and, regardless of name, can occur in most places on the leeward side of a nearby mountain range. They are called "Chinook winds" throughout most of inland western North America, particularly the Rocky Mountain region. Montana, in particular, has a significant amount of föhn winds across much of the state during the winter months, but particularly coming off the Rocky Mountain Front in the northern and west-central areas of the state.

One such wind occurs in the Cook Inlet region in Alaska as air moves over the Chugach Mountains between Prince William Sound and Portage Glacier. Anchorage residents often believe the warm winds which melt snow and leave their streets slushy and muddy are a midwinter gift from Hawaii, following a common mistake that the warm winds come from the same place as the similar winds near the coasts in southern British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon.

See also

References

- ↑ "Chinook". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. .

- 1 2 The Indian and the South Wind, p.156 Archived 2008-05-30 at the Wayback Machine., p.157 Archived 2008-05-30 at the Wayback Machine., p.158 Archived 2008-05-30 at the Wayback Machine. in J.A. Costello's Indian History of the Northwest – Siwash, 1909

- ↑ Andrew H. Horvitz, et al. On September 13, 2002 citing a unanimous recommendation from the National Climate Extremes Committee, The Director of NCDC accepted the Loma, Montana 24-hour temperature change of 103F degrees, making it the new official national record.

- ↑ The Atlas of Canada – Weather Archived 2010-03-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "Daily Data Report for February 1992 – Claresholm Waterworks Station". Environment Canada. Environment Canada. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- 1 2 Whiteman, C. David (2000). Mountain Meteorology: Fundamentals and Applications. Oxford University Press. ISBN.

- ↑ The Facts on File Encyclopedia or Word and Phrase Origins, Checkmark Books, New York, 2000

- 1 2 Example of tshinook original pronunciation from Comparative vocabularies of the Indian tribes etc. by William Fraser Tolmie, 1884.

- ↑ Short Portage to Lillooet, Irene Edwards, self-published, Lillooet, various editions

- ↑ Lillooet Stories, Randy Bouchard and Dorothy Kennedy , Victoria Sound Heritage 6.1. (1977)

- ↑ Chinooks and Health. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ↑ "South Dakota Weather History and Trivia January". – National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service.

—Appendix I: – "Weather Extremes". – National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. – (Adobe Acrobat *.PDF document). - ↑ Parker, Watson (1981). – Deadwood: The Golden Years. – Lincoln, Nebraska: The University of Nebraska. – p.158. – ISBN 978-0-8032-8702-0.

- ↑ Burrows, Alvin. "The Chinook Winds". Yearbook of the Department of Agriculture. US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 6 February 2016.