Chinese painting

Chinese painting is one of the oldest continuous artistic traditions in the world. Painting in the traditional style is known today in Chinese as guóhuà (simplified Chinese: 国画; traditional Chinese: 國畫), meaning "national" or "native painting", as opposed to Western styles of art which became popular in China in the 20th century. Traditional painting involves essentially the same techniques as calligraphy and is done with a brush dipped in black ink or coloured pigments; oils are not used. As with calligraphy, the most popular materials on which paintings are made are paper and silk. The finished work can be mounted on scrolls, such as hanging scrolls or handscrolls. Traditional painting can also be done on album sheets, walls, lacquerware, folding screens, and other media.

The two main techniques in Chinese painting are:

- Gongbi (工筆), meaning "meticulous", uses highly detailed brushstrokes that delimits details very precisely. It is often highly coloured and usually depicts figural or narrative subjects. It is often practised by artists working for the royal court or in independent workshops.

- Ink and wash painting, in Chinese shui-mo (水墨, "water and ink") also loosely termed watercolour or brush painting, and also known as "literati painting", as it was one of the "Four Arts" of the Chinese Scholar-official class.[1] In theory this was an art practiced by gentlemen, a distinction that begins to be made in writings on art from the Song dynasty, though in fact the careers of leading exponents could benefit considerably.[2] This style is also referred to as "xieyi" (寫意) or freehand style.

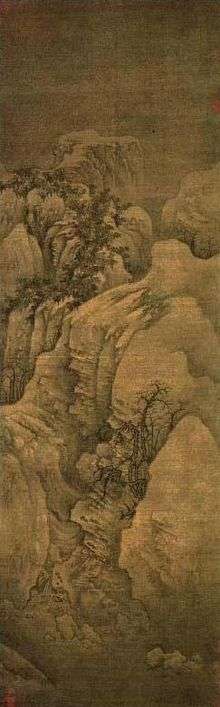

Landscape painting was regarded as the highest form of Chinese painting, and generally still is.[3] The time from the Five Dynasties period to the Northern Song period (907–1127) is known as the "Great age of Chinese landscape". In the north, artists such as Jing Hao, Li Cheng, Fan Kuan, and Guo Xi painted pictures of towering mountains, using strong black lines, ink wash, and sharp, dotted brushstrokes to suggest rough stone. In the south, Dong Yuan, Juran, and other artists painted the rolling hills and rivers of their native countryside in peaceful scenes done with softer, rubbed brushwork. These two kinds of scenes and techniques became the classical styles of Chinese landscape painting.

Specifics and study

Chinese painting and calligraphy distinguish themselves from other cultures' arts by emphasis on motion and change with dynamic life.[4] The practice is traditionally first learned by rote, in which the master shows the "right way" to draw items. The apprentice must copy these items strictly and continuously until the movements become instinctive. In contemporary times, debate emerged on the limits of this copyist tradition within modern art scenes where innovation is the rule. Changing lifestyles, tools, and colors are also influencing new waves of masters.[4][5]

Early periods

The earliest paintings were not representational but ornamental; they consisted of patterns or designs rather than pictures. Early pottery was painted with spirals, zigzags, dots, or animals. It was only during the Warring States period (475-221 BC) that artists began to represent the world around them. In imperial times (beginning with the Eastern Jin dynasty), painting and calligraphy in China were among the most highly appreciated arts in the court and they were often practiced by amateurs—aristocrats and scholar-officials—who had the leisure time necessary to perfect the technique and sensibility necessary for great brushwork. Calligraphy and painting were thought to be the purest forms of art. The implements were the brush pen made of animal hair, and black inks made from pine soot and animal glue. In ancient times, writing, as well as painting, was done on silk. However, after the invention of paper in the 1st century AD, silk was gradually replaced by the new and cheaper material. Original writings by famous calligraphers have been greatly valued throughout China's history and are mounted on scrolls and hung on walls in the same way that paintings are.

Artists from the Han (206 BC – 220 AD) to the Tang (618–906) dynasties mainly painted the human figure. Much of what we know of early Chinese figure painting comes from burial sites, where paintings were preserved on silk banners, lacquered objects, and tomb walls. Many early tomb paintings were meant to protect the dead or help their souls to get to paradise. Others illustrated the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius or showed scenes of daily life.

During the Six Dynasties period (220–589), people began to appreciate painting for its own beauty and to write about art. From this time we begin to learn about individual artists, such as Gu Kaizhi. Even when these artists illustrated Confucian moral themes – such as the proper behavior of a wife to her husband or of children to their parents – they tried to make the figures graceful.

Six principles

The "Six principles of Chinese painting" were established by Xie He, a writer, art historian and critic in 5th century China, in "Six points to consider when judging a painting" (繪畫六法, Pinyin: Huìhuà Liùfǎ), taken from the preface to his book "The Record of the Classification of Old Painters" (古畫品錄; Pinyin: Gǔhuà Pǐnlù). Keep in mind that this was written circa 550 CE and refers to "old" and "ancient" practices. The six elements that define a painting are:

- "Spirit Resonance", or vitality, which refers to the flow of energy that encompasses theme, work, and artist. Xie He said that without Spirit Resonance, there was no need to look further.

- "Bone Method", or the way of using the brush, refers not only to texture and brush stroke, but to the close link between handwriting and personality. In his day, the art of calligraphy was inseparable from painting.

- "Correspondence to the Object", or the depicting of form, which would include shape and line.

- "Suitability to Type", or the application of color, including layers, value, and tone.

- "Division and Planning", or placing and arrangement, corresponding to composition, space, and depth.

- "Transmission by Copying", or the copying of models, not from life only but also from the works of antiquity.

Sui and Tang dynasties (581–907)

During the Tang dynasty, figure painting flourished at the royal court. Artists such as Zhou Fang depicted the splendor of court life in paintings of emperors, palace ladies, and imperial horses. Figure painting reached the height of elegant realism in the art of the court of Southern Tang (937–975).

Most of the Tang artists outlined figures with fine black lines and used brilliant color and elaborate detail. However, one Tang artist, the master Wu Daozi, used only black ink and freely painted brushstrokes to create ink paintings that were so exciting that crowds gathered to watch him work. From his time on, ink paintings were no longer thought to be preliminary sketches or outlines to be filled in with color. Instead, they were valued as finished works of art.

Beginning in the Tang Dynasty, many paintings were landscapes, often shanshui (山水, "mountain water") paintings. In these landscapes, monochromatic and sparse (a style that is collectively called shuimohua), the purpose was not to reproduce the appearance of nature exactly (realism) but rather to grasp an emotion or atmosphere, as if catching the "rhythm" of nature.

Song and Yuan dynasties (960–1368)

_001.jpg)

Painting during the Song dynasty (960–1279) reached a further development of landscape painting; immeasurable distances were conveyed through the use of blurred outlines, mountain contours disappearing into the mist, and impressionistic treatment of natural phenomena. The shan shui style painting—"shan" meaning mountain, and "shui" meaning river—became prominent in Chinese landscape art. The emphasis laid upon landscape was grounded in Chinese philosophy; Taoism stressed that humans were but tiny specks in the vast and greater cosmos, while Neo-Confucianist writers often pursued the discovery of patterns and principles that they believed caused all social and natural phenomena.[6] The painting of portraits and closely viewed objects like birds on branches were held in high esteem, but landscape painting was paramount.[7] By the beginning of the Song Dynasty a distinctive landscape style had emerged.[8] Artists mastered the formula of intricate and realistic scenes placed in the foreground, while the background retained qualities of vast and infinite space. Distant mountain peaks rise out of high clouds and mist, while streaming rivers run from afar into the foreground.[9]

There was a significant difference in painting trends between the Northern Song period (960–1127) and Southern Song period (1127–1279). The paintings of Northern Song officials were influenced by their political ideals of bringing order to the world and tackling the largest issues affecting the whole of society; their paintings often depicted huge, sweeping landscapes.[10] On the other hand, Southern Song officials were more interested in reforming society from the bottom up and on a much smaller scale, a method they believed had a better chance for eventual success; their paintings often focused on smaller, visually closer, and more intimate scenes, while the background was often depicted as bereft of detail as a realm without concern for the artist or viewer.[10] This change in attitude from one era to the next stemmed largely from the rising influence of Neo-Confucian philosophy. Adherents to Neo-Confucianism focused on reforming society from the bottom up, not the top down, which can be seen in their efforts to promote small private academies during the Southern Song instead of the large state-controlled academies seen in the Northern Song era.[11]

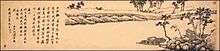

Ever since the Southern and Northern dynasties (420–589), painting had become an art of high sophistication that was associated with the gentry class as one of their main artistic pastimes, the others being calligraphy and poetry.[12] During the Song Dynasty there were avid art collectors that would often meet in groups to discuss their own paintings, as well as rate those of their colleagues and friends. The poet and statesman Su Shi (1037–1101) and his accomplice Mi Fu (1051–1107) often partook in these affairs, borrowing art pieces to study and copy, or if they really admired a piece then an exchange was often proposed.[13] They created a new kind of art based upon the three perfections in which they used their skills in calligraphy (the art of beautiful writing) to make ink paintings. From their time onward, many painters strove to freely express their feelings and to capture the inner spirit of their subject instead of describing its outward appearance. The small round paintings popular in the Southern Song were often collected into albums as poets would write poems along the side to match the theme and mood of the painting.[10]

Although they were avid art collectors, some Song scholars did not readily appreciate artworks commissioned by those painters found at shops or common marketplaces, and some of the scholars even criticized artists from renowned schools and academies. Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, a Professor of Early Chinese History at the University of California, Santa Barbara, points out that Song scholars' appreciation of art created by their peers was not extended to those who made a living simply as professional artists:[15]

During the Northern Song (960–1126 CE), a new class of scholar-artists emerged who did not possess the tromp l'œil skills of the academy painters nor even the proficiency of common marketplace painters. The literati's painting was simpler and at times quite unschooled, yet they would criticize these other two groups as mere professionals, since they relied on paid commissions for their livelihood and did not paint merely for enjoyment or self-expression. The scholar-artists considered that painters who concentrated on realistic depictions, who employed a colorful palette, or, worst of all, who accepted monetary payment for their work were no better than butchers or tinkers in the marketplace. They were not to be considered real artists.[15]

However, during the Song period, there were many acclaimed court painters and they were highly esteemed by emperors and the royal family. One of the greatest landscape painters given patronage by the Song court was Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145), who painted the original Along the River During the Qingming Festival scroll, one of the most well-known masterpieces of Chinese visual art. Emperor Gaozong of Song (1127–1162) once commissioned an art project of numerous paintings for the Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute, based on the woman poet Cai Wenji (177–250 AD) of the earlier Han dynasty. Yi Yuanji achieved a high degree of realism painting animals, in particular monkeys and gibbons.[16] During the Southern Song period (1127–1279), court painters such as Ma Yuan and Xia Gui used strong black brushstrokes to sketch trees and rocks and pale washes to suggest misty space.

During the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), painters joined the arts of painting, poetry, and calligraphy by inscribing poems on their paintings. These three arts worked together to express the artist's feelings more completely than one art could do alone. Yuan emperor Tugh Temur (r. 1328, 1329–1332) was fond of Chinese painting and became a creditable painter himself.

Late imperial China (1368–1895)

Beginning in the 13th century, the tradition of painting simple subjects—a branch with fruit, a few flowers, or one or two horses—developed. Narrative painting, with a wider color range and a much busier composition than Song paintings, was immensely popular during the Ming period (1368–1644).

The first books illustrated with colored woodcuts appeared around this time; as color-printing techniques were perfected, illustrated manuals on the art of painting began to be published. Jieziyuan Huazhuan (Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden), a five-volume work first published in 1679, has been in use as a technical textbook for artists and students ever since.

Some painters of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) continued the traditions of the Yuan scholar-painters. This group of painters, known as the Wu School, was led by the artist Shen Zhou. Another group of painters, known as the Zhe School, revived and transformed the styles of the Song court.

During the early Qing dynasty (1644–1911), painters known as Individualists rebelled against many of the traditional rules of painting and found ways to express themselves more directly through free brushwork. In the 18th and 19th centuries, great commercial cities such as Yangzhou and Shanghai became art centers where wealthy merchant-patrons encouraged artists to produce bold new works.

In the late 19th and 20th centuries, Chinese painters were increasingly exposed to Western art. Some artists who studied in Europe rejected Chinese painting; others tried to combine the best of both traditions. Among the most beloved modern painters was Qi Baishi, who began life as a poor peasant and became a great master. His best-known works depict flowers and small animals.

Modern painting

Beginning with the New Culture Movement, Chinese artists started to adopt using Western techniques.

In the early years of the People's Republic of China, artists were encouraged to employ socialist realism. Some Soviet Union socialist realism was imported without modification, and painters were assigned subjects and expected to mass-produce paintings. This regimen was considerably relaxed in 1953, and after the Hundred Flowers Campaign of 1956-57, traditional Chinese painting experienced a significant revival. Along with these developments in professional art circles, there was a proliferation of peasant art depicting everyday life in the rural areas on wall murals and in open-air painting exhibitions.

During the Cultural Revolution, art schools were closed, and publication of art journals and major art exhibitions ceased. Major destruction was also carried out as part of the elimination of Four Olds campaign.

Since 1978

Following the Cultural Revolution, art schools and professional organizations were reinstated. Exchanges were set up with groups of foreign artists, and Chinese artists began to experiment with new subjects and techniques. One particular case of freehand style (xieyi hua) may be noted in the work of the child prodigy Wang Yani (born 1975) who started painting at age 3 and has since considerably contributed to the exercise of the style in contemporary artwork.

After Chinese economic reform, more and more artists boldly conducted innovations in Chinese Painting. The innovations include: development of new brushing skill such as vertical direction splash water and ink, with representative artist Tiancheng Xie,[17] creation of new style by integration traditional Chinese and Western painting techniques such as Heaven Style Painting, with representative artist Shaoqiang Chen,[18] and new styles that express contemporary theme and typical nature scene of certain regions such as Lijiang Painting Style,with representative artist Gesheng Huang.[19]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paintings from China. |

- Bird-and-flower painting

- Chinese art

- Chinese Piling paintings

- Eastern art history

- Eight Views of Xiaoxiang

- History of painting

- Lin Tinggui

- List of Chinese painters

- Qiu Ying

- Three perfections - integration of calligraphy, poetry and painting

- Mu Qi

- Wǔ Xíng painting

- Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou

- Japanese painting

- Korean painting

Notes

- ↑ Sickman, 222

- ↑ Rawson, 114–119; Sickman, Chapter 15

- ↑ Rawson, 112

- 1 2 (Stanley-Baker 2010a)

- ↑ (Stanley-Baker 2010b)

- ↑ Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 162.

- ↑ Morton, 104.

- ↑ Barnhart, "Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting", 93.

- ↑ Morton, 105.

- 1 2 3 Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 163.

- ↑ Walton, 199.

- ↑ Ebrey, 81–83.

- ↑ Ebrey, 163.

- ↑ Shao Xiaoyi. "Yue Fei's facelift sparks debate". China Daily. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- 1 2 Barbieri-Low (2007), 39–40.

- ↑ Robert van Gulik, "Gibbon in China. An essay in Chinese Animal Lore". The Hague, 1967.

- ↑ 宏然天成:谢天成泼墨山水技法,百度百科 http://baike.baidu.com/view/8312263.htm

- ↑ "【社团风采】——"天堂画派"艺术家作品选刊("书法报·书画天地",2015年第2期第26-27版)". qq.com. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ 漓江画派,百度百科 http://baike.baidu.com/view/200826.htm

References

- Rawson, Jessica (ed). The British Museum Book of Chinese Art, 2007 (2nd edn), British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714124469

- Stanley-Baker, Joan (May 2010a), Ink Painting Today (PDF), 10 (8), Centered on Taipei, pp. 8–11

- Sickman, Laurence, in: Sickman L & Soper A, "The Art and Architecture of China", Pelican History of Art, 3rd ed 1971, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), LOC 70-125675

- Stanley-Baker, Joan (June 2010b), Ink Painting Today (PDF), 10 (9), Centered on Taipei, pp. 18–21

Further reading

- Fong, Wen (1973). Sung and Yuan paintings. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870990845. Fully online from the MMA

- Liu , Shi-yee (2007). Straddling East and West: Lin Yutang, a modern literatus: the Lin Yutang family collection of Chinese painting and calligraphy. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588392701.

External links

- Chinese Painting at China Online Museum

- Famous Chinese painters and their galleries

- Chinese painting Technique and styles

- Cuiqixuan - Inside painting snuff bottles

- Between two cultures : late-nineteenth- and twentieth-century Chinese paintings from the Robert H. Ellsworth collection in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Fully online from the MMA

- A Pure and Remote View: Visualizing Early Chinese Landscape Painting: a series of more than 20 video lectures by James Cahill.

- Gazing Into The Past - Scenes From Later Chinese & Japanese Painting: a series of video lecture by James Cahill.