Chinese pagoda

- For the landmark in Birmingham, see Chinese Pagoda.

Chinese pagodas (Chinese: 塔; pinyin: Tǎ) are a traditional part of Chinese architecture. In addition to religious use, since ancient times Chinese pagodas have been praised for the spectacular views which they are built to offer, and many famous poems in Chinese history attest to the joy of scaling pagodas. The oldest and tallest were built of wood, but those which have endured over time have been built of brick or stone. Some pagodas were solid, and had no interior at all; others were hollow and held within themselves an altar, with the larger frequently containing a smaller pagoda (pagodas were not inhabited buildings and had no "floors" or "rooms"). The pagoda's interior has a series of staircases that allow the visitor to ascend to the top of the building and to witness the view from an opening on one side at each storey. Most have between three and 13 storeys (almost always an odd number) and the classic gradual tiered eaves.[1][2]

History

Earliest base-structure type for Chinese pagodas were square-base and circular-base. By the 5th-10th centuries the Chinese began to build octagonal-base pagoda towers. The highest Chinese pagoda from the pre-modern age is the Liaodi Pagoda of Kaiyuan Monastery, Dingxian, Hebei province, completed in the year 1055 AD under Emperor Renzong of Song and standing at a total height of 84 m (275 ft). Although it no longer stands, the tallest pre-modern pagoda in Chinese history was the 100-metre-tall wooden pagoda (330 ft) of Chang'an, built by Emperor Yang of Sui.[3] The Liaodi Pagoda is the tallest pre-modern pagoda still standing, yet in April 2007 a new wooden pagoda at the Tianning Temple of Changzhou was opened to the public; this pagoda is now the tallest in China, standing at 154 m (505 ft).

Symbolism and geomancy

Iconography of Han is noticeable in architecture of the Chinese Pagoda. The image of the Shakyamuni Buddha in the abhaya mudra is also noticeable in some Chinese pagodas. Buddhist iconography is also inside of the symbolism in the pagoda.[4] In an article on Buddhist elements in Han art, Wu Hung suggests that in these tombs, Buddhist iconography was so well incorporated into native Chinese traditions that a unique system of symbolism had been developed.[5] It was believed by some that they would influence the success of young students taking the examinations for a civil service degree.[6] When a pagoda of Yihuang County in Fuzhou collapsed in 1210 during the Song Dynasty, all the local inhabitants believed that the unfortunate event was directly correlated with the recent failure of many exam candidates in the prefectural examinations for official degrees, the prerequisite for appointment in civil service.[7] The pagoda was rebuilt in 1223 and had a list inscribed on it of the recently successful examination candidates, in hopes that it would reverse the trend and win the county supernatural, cosmic favor.[7]

Construction Materials

Wood

From the Eastern Han Dynasty to the Southern and Northern Dynasties (~25-589) pagodas were mostly built of wood, as were other ancient Chinese structures. Wooden pagodas are resistant to earthquakes, however many have burnt down, and wood is also prone to both natural rot and insect infestation.

Examples of wooden pagodas:

- White Horse Pagoda at White Horse Temple, Luoyang.

- Futuci Pagoda in Xuzhou, built in the Three Kingdoms period (~220-265).

- Many of the pagodas in Stories About Buddhist Temples in Luoyang, a Northern Wei text, were wooden.

The literature of subsequent eras also provides evidence of the domination of wooden pagoda construction in this period. The famous Tang Dynasty poet, Du Mu, once wrote:

- 480 Buddhist temples of the Southern Dynasties,

- uncountable towers and pagodas stand in the misty rain.

The oldest extant fully wooden pagoda standing in China today is the Pagoda of Fugong Temple in Ying County, Shanxi Province, built in the 11th century during the Song Dynasty/Liao Dynasty (refer to Architecture section in Song Dynasty).

Transition to brick and stone

During the Northern Wei and Sui dynasties (386-618) experiments began with the construction of brick and stone pagodas. Even at the end of the Sui, however, wood was still the most common material. For example, Emperor Wen of the Sui Dynasty (reigned 581-604) once issued a decree for all counties and prefectures to build pagodas to a set of standard designs, however since they were all built of wood none have survived. Only the Songyue Pagoda has survived, a circular-based pagoda built out of stone in 523 AD.

Brick

The earliest extant brick pagoda is the 40-metre-tall Songyue Pagoda in Dengfeng Country, Henan.[8] This curved, circle-based pagoda was built in 523 during the Northern Wei Dynasty, and has survived for 15 centuries.[8] Much like the later pagodas found during the following Tang Dynasty, this temple featured tiers of eaves encircling its frame, as well as a spire crowning the top. Its walls are 2.5 m thick, with a ground floor diameter of 10.6 m. Another early brick pagoda is the Sui Dynasty Guoqing Pagoda built in 597.

Stone

The earliest large-scale stone pagoda is a Four Gates Pagoda at Licheng, Shandong, built in 611 during the Sui Dynasty. Like the Songyue Pagoda, it also features a spire at its top, and is built in the pavilion style.

Brick and stone

One of the earliest brick and stone pagodas was a three-storey construction built in the (first) Jin Dynasty (265-420), by Wang Jun of Xiangyang. However, it is now destroyed.

Brick and stone went on to dominate Tang, Song, Liao and Jin Dynasty pagoda construction. An example of such would be the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda (652 AD), built during the early Tang Dynasty. The Porcelain Pagoda of Nanjing has been one of the most famous brick and stone pagoda in China throughout history. The Zhou dynasty started making the ancient pagodas about 3,500 years ago and are still being made today.

De-emphasis over time

Pagodas, in keeping with the tradition of the White Horse Temple, were generally placed in the center of temples until the Sui and Tang dynasties. During the Tang, the importance of the main hall was elevated and the pagoda was moved beside the hall, or out of the temple compound altogether. In the early Tang, Dàoxuān wrote a Standard Design for Buddhist Temple Construction in which the main hall replaced the pagoda as the center of the temple.

The design of temples was also influenced by the use of traditional Chinese residences as shrines, after they were philanthropically donated by the wealthy or the pious. In such pre-configured spaces, building a central pagoda might not have been either desirable or possible.

In the Song Dynasty (960-1279), the Chan (Zen) sect developed a new 'seven part structure' for temples. The seven parts - the Buddha hall, dharma hall, monks' quarters, depository, gate, pure land hall and toilet facilities - completely exclude pagodas, and can be seen to represent the final triumph of the traditional Chinese palace/courtyard system over the original central-pagoda tradition established 1000 years earlier by the White Horse Temple in 67. Although they were built outside of the main temple itself, large pagodas in the tradition of the past were still built. This includes the two Ming Dynasty pagodas of Famen Temple and the Chongwen Pagoda in Jingyang of Shaanxi Province.

A prominent, later example of converting a palace to a temple is Beijing's Yonghe Temple, which was the residence of Yongzheng Emperor before he ascended the throne. It was donated for use as a lamasery after his death in 1735.

Styles of eras

Han Dynasty

Examples of Han Dynasty era tower architecture predating Buddhist influence and the full-fledged Chinese pagoda can be seen in the four pictures below. Michael Loewe writes that during the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) period, multi-storied towers were erected for religious purposes, as astronomical observatories, as watchtowers, or as ornate buildings that were believed to attract the favor of spirits, deities, and immortals.[9]

- Ancient Chinese model of two residential towers, made of earthenware during the Han Dynasty, 2nd century BC to 2nd century AD

- Side view of a Han pottery tower model with a mid-floor balcony and a courtyard gatehouse flanked by smaller towers; the dougong support brackets are clearly visible.

- A Western-Han model of a watchtower with human figures on its balconies (including crossbowmen) and a gatehouse and courtyard on the first floor

- Among a large set of architectural models, three Eastern Han Dynasty watchtowers stand in the rear of this display

Sui and Tang

Pagodas built during the Sui and Tang Dynasty usually had a square base, with a few exceptions such as the Daqin Pagoda:

Four Gates Pagoda, built in 611.

Four Gates Pagoda, built in 611. The Daqin Pagoda, built in 640.

The Daqin Pagoda, built in 640.- The Small Wild Goose Pagoda, built in 709.

Pagoda of the Baoguang Temple, built between 862-888.

Pagoda of the Baoguang Temple, built between 862-888.

Dali kingdom

The Three Pagodas, 9th and 10th centuries.

The Three Pagodas, 9th and 10th centuries.

Song, Liao, Jin, Yuan

Pagodas of the Five Dynasties, Northern and Southern Song, Liao, Jin, and Yuan Dynasties incorporated many new styles, with a greater emphasis on hexagonal and octagonal bases for pagodas:

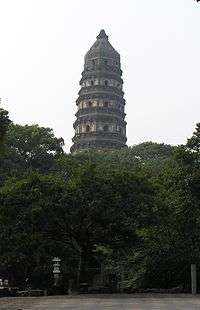

The Huqiu Tower, built in 961.

The Huqiu Tower, built in 961.- Longhua Pagoda, built in 977.

Pagoda of Fogong Temple, built in 1056.

Pagoda of Fogong Temple, built in 1056. The Liaodi Pagoda, built in 1055

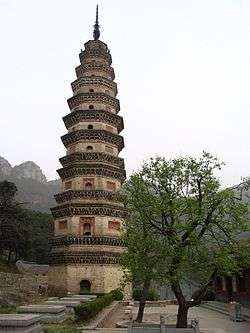

The Liaodi Pagoda, built in 1055 Pizhi Pagoda, built by 1063.

Pizhi Pagoda, built by 1063. Haotian Pagoda, built in 1103.

Haotian Pagoda, built in 1103.- The Chengling Pagoda, built in 1189.

Pagoda of Bailin Temple, built by 1330.

Pagoda of Bailin Temple, built by 1330.

Ming and Qing

Pagodas in the Ming and Qing Dynasties generally inherited the styles of previous eras, although there were some minor variations:

Zhenjue Temple, built in 1473.

Zhenjue Temple, built in 1473.- The Pagoda of Cishou Temple, built in 1576.

- The Sarira Stupa of Tayuan Temple, built in 1582

- The Fragrant Hills Pagoda, built in 1780.

The Square Tower of Songjiang, Shanghai

The Square Tower of Songjiang, Shanghai

See also

Notes

- ↑ Architecture and Building. W.T. Comstock. 1896. p. 245.

- ↑ Steinhardt, 387.

- ↑ Benn, 62.

- ↑ The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture By John Kieschnick. Published 2003. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09676-7. page 83

- ↑ The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture By John Kieschnick. Published 2003. Princeton University Press ISBN 0-691-09676-7. page 84

- ↑ Brook, 7.

- 1 2 Hymes, 30.

- 1 2 Steinhardt, 383.

- ↑ Loewe (1968), 133.

References

- Benn, Charles (2002). China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517665-0.

- Brook, Timothy. (1998). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22154-0

- Fu, Xinian. (2002). "The Three Kingdoms, Western and Eastern Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties," in Chinese Architecture, 61–90. Edited by Nancy S. Steinhardt. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09559-7.

- Hymes, Robert P. (1986). Statesmen and Gentlemen: The Elite of Fu-Chou, Chiang-Hsi, in Northern and Southern Sung. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-30631-0.

- Loewe, Michael. (1968). Everyday Life in Early Imperial China during the Han Period 202 BC–AD 220. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd.; New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman (1997). Liao Architecture. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pagodas in China. |

- Chinese pagoda gallery (211 pics)

- The Bei-Hai (Beijing), The Flower Pagoda (Guangdong), The Great Gander Pagoda (Xian), The White Pagoda (Liaoyang)

- With a chapter about China and paragraphs about many pagoda’s

- The Songyue Pagoda at China.org.cn

- Structure of Pagodas, including the underground palace, base, body and steeple, at China.org.cn

- The Herbert Offen Research Collection of the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum