Chinatown, Chicago

| Chinatown, Chicago | |

|---|---|

| Neighborhood | |

|

Cermak Road including the Chinatown Gate over Wentworth Avenue | |

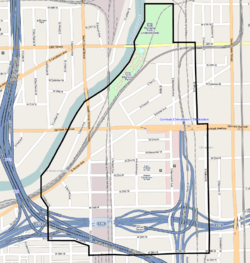

Map of Chinatown | |

| Coordinates: 41°51′10″N 87°37′55″W / 41.852861°N 87.631894°WCoordinates: 41°51′10″N 87°37′55″W / 41.852861°N 87.631894°W | |

| Country | United States |

| City | Chicago |

| Community areas | Armour Square |

| First settled | 1912 |

| Population [1][2] | |

| • Estimate (2010) | 16,325 |

| ZIP code | 60616 |

The Chinatown neighborhood in Chicago, Illinois, is on the South Side (located in the Armour Square community area), centered on Cermak and Wentworth Avenues, and is an example of an American Chinatown, or ethnic-Chinese neighborhood. By the 2000 Census, Chicago Primary Metropolitan Statistical Area had 68,021 Chinese.[3] The combined 60616 and 60608 zip codes in Chicago, as of the 2010 Census, were home to 22,380 people of Chinese descent. In addition, as of 2010, the Chicago-Joliet-Naperville IL-IN-WI metro area had 92,712 people of Chinese descent.[4] Chicago is the second oldest settlement of Chinese in America after the Chinese fled persecution in California. The present Chicago Chinatown formed about 1915, after settlers moved steadily south from near the Loop where the first enclaves were established in the 19th century.

Chinatown is sometimes confused with an area on the city's North Side sometimes referred to as "New Chinatown", which is centered on Argyle Street and is somewhat of a misnomer given that it is largely populated by people of Southeast Asian heritage.

History

Looking to escape the anti-Chinese violence that had broken out on the west coast, the first Chinese arrived in Chicago after 1869 when the First Transcontinental Railroad was completed.[5] By the late 1800s, 25% of Chicago's approximately 600 Chinese residents settled along Clark Street between Van Buren and Harrison Streets in Chicago's Loop.[6] In 1889, 16 Chinese-owned businesses were located along the two-block stretch, including eight grocery stores, two butcher shops and a restaurant.[7] In 1912, the Chinese living in this area began moving south to Armour Square. Some historians say this was due to increasing rent prices.[6][8] Others see more complex causes: discrimination, overcrowding, a high non-Chinese crime rate, and disagreements between the two associations ("tongs") within the community, the Hip Sing Tong and the On Leong Tong.[9][10] The move to the new South Side Chinatown was led by the On Leong Merchants Association who, in 1912, had a building constructed along Cermak Avenue (then 22nd Street) that could house 15 stores, 30 apartments and the Association's headquarters. While the building's design was typical of the period, it also featured Chinese accents such as tile trim adorned with dragons.[11]

In the 1920s, Chinese community leaders secured approximately 50 ten-year leases on properties in the newly developing Chinatown.[12] Because of severe racial discrimination, these leases needed to be secured via an intermediary, H. O. Stone Company.[8] Jim Moy, then-director of the On Leong Merchants Association, then decided that a Chinese-style building should be constructed as a strong visual announcement of the Chinese community's new presence in the area.[12][13] With no Chinese-born architects in Chicago at the time, Chicago-born Norse architects Christian S. Michaelsen and Sigurd A. Rognstad were asked to design the new On Leong Merchants Association Building in spring, 1926.[14] Michaelsen and Rognstad drew their final design after studying texts on Chinese architecture.[12][15][16] When the building opened in 1928 at a cost of a million dollars, it was the finest large Chinese-style structure in any North American Chinatown.[17] The On Leong Association allowed the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association to put its headquarters in the new building and also used it as an immigrant assistance center, a school, a shrine, a meeting hall, and office space for the Association itself.[18][19] It was often informally referred to as Chinatown's "city hall."[12] In 1928, Michaelsen and Rognstad designed two other buildings in the area—Won Kow Restaurant, Chinatown's oldest restaurant,[20] and the Moy Shee D.K Association Building, the former receiving a two-story addition in 1932.[21]

During the late 1980s, a group of Chinatown business leaders bought 32 acres (130,000 m2) property north of Archer Avenue from the Santa Fe Railway and built Chinatown Square, a two-level mall consisting of restaurants, beauty salons and law offices, flanked by 21 new townhouses. Additional residential construction, such as the Santa Fe Gardens, a 600-unit village of townhouses, condominiums and single-family homes still under construction on formerly industrial land to the north.[22] Perhaps the most outstanding feature of the new addition was the creation of Ping Tom Memorial Park in 1999; located on the bank of the Chicago River, the park features a Chinese-style pavilion that many consider to be the most beautiful in the Midwest.[23]

Historical images of Chinatown can be found in Explore Chicago Collections, a digital repository made available by Chicago Collections archives, libraries and other cultural institutions in the city.[24]

Commerce

| Chinatown, Chicago | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Wentworth Avenue looking south. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 芝加哥華埠 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 芝加哥华埠 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chicago's Chinatown is home to a number of banks, Chinese restaurants, gift shops, grocery stores, Chinese medicine stores, as well as a number of services that cater to people interested in Chinese culture, including those speaking varieties of Chinese, especially Cantonese. It is a community hub for Chinese people in the Chicago metropolitan area, a business center for Chinese in the Midwest, as well as a popular destination for tourists and locals alike.

As of 2013 most area businesses cater to the local Chinese population as the majority of area residents are ethnic Chinese.[25] As of 2013 the community does not have a lot of nightlife-oriented establishments.[26]

Demographics

As of 2013 about 8,000 people lived within Chinatown itself, and 90% were ethnic Chinese.[25] As of that year many of the residents were elderly.[26]

As of 1990 about 10,000 Chinese lived in Chinatown's business district and the area south of 26th street, and several Italian Americans still remained in the neighborhood.[27]

Landmarks and attractions

- Chinatown Mural, a mural showing the history of Chinese immigrants in United States

- Chinatown Square, Shopping area opened in 1993. Decorated with sculptures of animals in the Chinese zodiac

- Wentworth Avenue, with shopping, restaurants, and landmarks, including the Chinatown Gate

- Pui Tak Center was designated a Chicago Landmark on December 1, 1993. It was the On Leong Merchants Association Building.

- Chinese-American Museum of Chicago, conducts research and exhibits objects and pictures relating to the history of Chinese in the American Midwest. The museum experienced a fire on September 19, 2008 and was temporarily closed. Thanks to strong community support, it reopened in the fall of 2010 with improved facilities.

- Ping Tom Memorial Park, Opened in 1999 with Chinese gardens on the northern edge of Chinatown along the Chicago River

- Chicago Fire Department Engine 8 Company firehouse, firehouse used in the 1991 Ron Howard film Backdraft

- Chinatown Gate, which spans Wentworth Avenue at the intersection of Cermak Road, designed by Peter Fung

Government and infrastructure

The United States Postal Service operates the Chinatown Post Office at 2345 South Wentworth Avenue.[28]

Education

Primary and secondary schools

Residents are zoned to schools in the Chicago Public Schools including John C. Haines School (興氏學校; 兴氏学校; Xīngshì Xuéxiào; hing1 si6 hok6 haau6) and Phillips Academy High School.[29][30]

Haines serves students from Chinatown and formerly from the Harold L. Ickes Homes; students from the latter used a tunnel to get to school. As of 2001 70% of the students were Asian while 28% were black; most residents of Ickes were black.[31] Connie Laureman of the Chicago Tribune stated that Haines, in 1990, was "crowded and dilapidated".[32] Until Gandy Easton became principal in 1990, the school had de facto racial segregation as ethnic Chinese students stayed in a bilingual program while black students took regular classes. Easton combined the two levels together, despite protests from ethnic Chinese parents.[31] By 2001 school authorities instituted programs to combat racism and ensure Chinese and black students socialized with one another.[33]

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago supports the St. Therese Chinese Catholic School, a K-8 private Catholic school.[34] As of 1990 almost all of the students were ethnic Chinese.[32]

The Pui Tak Christian School (培德基督教學校; 培德基督教学校; Péidé Jīdūjiào Xuéxiào; pui4 dak1 gei1 duk1 gaau3 hok6 haau6) is a private pre-kindergarten to 6th grade school.[35]

Public libraries

The Chicago Public Library operates the Chinatown Library at 2100 South Wentworth Avenue.[36]

Culture

A 1942 article from the Chicago Tribune stated that the strong family ties among the residents of Chinatown meant that there was little juvenile delinquency present in the community.[37]

Transportation

The Dan Ryan Expressway and the Stevenson Expressway intersect over the southside of Chinatown. The Stevenson's exit 293A (northbound exit and southbound entrances) gives Chinatown commuters immediate access to the expressways via Cermak Road, only one block east of Wentworth Avenue. There is metered street parking throughout the area, as well as two pay parking lots located on Wentworth Avenue.[38]

Several forms of public transportation are also available in Chinatown. The Chicago Transit Authority operates both an elevated train and four bus routes that service the area. The Red Line, the CTA's busiest transit route, stops 24/7 at the Cermak–Chinatown station located in the heart of Chinatown near the corner of Cermak Road and Wentworth Avenue.[39][40] Running north–south, the #24 bus route runs on Wentworth Avenue on the eastside of Chinatown, while the #44 route runs on Canal Street on the westside. The #21 runs east–west on Cermak Road, and the #62 runs southwest–northeast on Archer Avenue.[41] There is a taxicab stand on Wentworth Avenue, and a water taxi service also runs along the Chicago River from Michigan Avenue to Ping Tom Memorial Park in Chinatown during the summer months.[1]

Annual events

- Chinatown 5K

- Chinese New Year Festival

- Dragon Boat Races

See also

References

- 1 2 Laffey, Mary Lu (2009-06-26). "Chinatown: A 'hidden jewel' worth seeking". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2009-08-11.

- ↑ Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "American FactFinder - Results". census.gov. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ↑ ftp://ftp2.census.gov/census_2000/datasets/demographic_profile/Illinois/2kh17.pdf

- ↑ Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "American FactFinder - Results". census.gov. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ↑ Ho 2005, p. 9.

- 1 2 Kiang 2008

- ↑ Malooley, Jake (April 29, 2010). "It happened here - Chicago's original Chinatown". Time Out Chicago. Time Out Chicago Partners (270): 6.

- 1 2 Solzman 2008

- ↑ Bronson, Chiu & Ho 2011, p. 9

- ↑ Moy 1995, p 382

- ↑ "Earliest South Side Chinatown: A Forgotten On Leong Building, ca. 1912". Chinese-American Museum of Chicago. July 14, 2005. Archived from the original on October 25, 2008. Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Leroux, Charles (January 6, 2002). "Still Standing - Living links to a rich history of commerce and culture". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- ↑ Ho 2005, p. 58.

- ↑ "Our Building". Chinese Christian Union Church. Archived from the original on June 25, 2008. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ Bronson, Chiu & Ho 2011, p 32-3

- ↑ "Pui Tak Building (formerly On Leong Building), 2216 S Wentworth Avenue". Chinese-American Museum of Chicago. August 7, 2005. Archived from the original on October 25, 2008. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ Bronson, Chiu & Ho 2011, p 32

- ↑ Herrmann, Andrew (November 17, 1995). "Chinese Church Gives Landmark A Rebuilt Image". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ "On Leong Merchants Association Building". City of Chicago Department of Planning and Development. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ Zeldes, Leah A. (January 27, 2006). "Chinese Chicago Where to soak up Chinatown's culture during - the Year of the Dog". Daily Herald. Newsbank. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ↑ Sinkevitch 2004, p. 372.

- ↑ Olivo, Antonio; Avila, Oscar (July 18, 2004). "Chinatown 's new reach expands its old borders". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved August 11, 2009.

- ↑ Bronson, Chiu & Ho 2011, p 51

- ↑ Long, Elizabeth. "A Single Portal to Chicago’s History". The University of Chicago News. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- 1 2 Lee, Sophia (2013-09-19). "Changing neighborhood, changing perceptions". Chicago Tribune. p. 1. Retrieved 2016-12-24.

- 1 2 Lee, Sophia (2013-09-19). "Changing neighborhood, changing perceptions". Chicago Tribune. p. 2. Retrieved 2016-12-24.

- ↑ Laureman, Connie (1990-07-15). "Changing Chinatown". Chicago Tribune. p. 2. Retrieved 2016-12-25.

- ↑ "Post Office Location - CHINATOWN." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on April 17, 2009.

- ↑ "Near North West Central Elementary Schools Archived June 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.." Chicago Public Schools. Retrieved on April 7, 2009.

- ↑ "West/Central/South High Schools Archived 2010-02-14 at WebCite." Chicago Public Schools. Retrieved on April 7, 2009.

- 1 2 Ahmed-Ullah, Noreen S. (2001-07-01). "School strives to expel racism". Chicago Tribune. p. 1. Retrieved 2016-12-24.

- 1 2 Laureman, Connie (1990-07-15). "Changing Chinatown". Chicago Tribune. p. 1. Retrieved 2016-12-24.

- ↑ Ahmed-Ullah, Noreen S. (2001-07-01). "School strives to expel racism". Chicago Tribune. p. 2. Retrieved 2016-12-24.

- ↑ "St. Therese Chinese Catholic School Archived 2009-06-27 at the Wayback Machine.." St. Therese Chinese Catholic Mission. Retrieved on April 17, 2009.

- ↑ "Pui Tak Christian School." Retrieved on May 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Chinatown Library." Chicago Public Library. Retrieved on April 17, 2009.

- ↑ "Few Bad Boys in Chinatown-Credit Family". Chicago Tribune. 1942-10-25. p. Part 3, Metropolitan Section, p. 1. - Image of the page - Continued on page 6 as "Love of Family Keeps Chinese Boys from Jail" - Page image

- ↑ "How to get here". Chicago Chinatown Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 2009-08-11.

- ↑ Planning and Development (2009-05-18). "Monthly Ridership Report - April 2009" (PDF). Chicago Transit Authority. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- ↑ "Cermak-Chinatown - Station Timetable" (PDF). Chicago Transit Authority. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- ↑ "Central Map System". Chicago Transit Authority. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

Further reading

- Bronson, Bennet; Chiu, Joe; Ho, Chuimei (2011). Chinatown in Chicago, A Visitor's Guide to its History and Architecture. Chinese American Museum of Chicago. ISBN 978-0-9840455-0-1.

- Ho, Chuimei (August 17, 2005). "Seeking a New World". In Ho, Chuimei; Moy, Soo Lon. Chinese in Chicago: 1870–1945. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-3444-7.

- Ho, Chuimei (August 17, 2005). "The Rise of Chinatown". In Ho, Chuimei; Moy, Soo Lon. Chinese in Chicago: 1870–1945. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-3444-7.

- Moy, Susan Lee (1995). "The Chinese in Chicago: The First Hundred Years". In Holli, Melvin G.; Jones, Peter d'A. Ethnic Chicago: A Multicultural Portrait. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-7053-7.

- Kiang, Harry (1992). Chicago's Chinatown (1st ed.). Lincolnwood, Ill: Institute of China Studies.

- Kiang, Harry (November 15, 2008). "Chinatown". In Keating, Ann Durkin. Chicago Neighborhoods and Suburbs: A Historical Guide. London: University of Chicago Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 0-226-42883-4.

- Sinkevitch, Alice (April 12, 2004). AIA guide to Chicago. Harvest Books. ISBN 0-15-602908-1.

- Solzman, David M. (November 15, 2008). "Armour Square". In Keating, Ann Durkin. Chicago Neighborhoods and Suburbs: A Historical Guide. London: University of Chicago Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 0-226-42883-4.

- Eltagour, Marwa (May 13, 2016). "Here's why Chicago's Chinatown is booming, even as others across the U.S. fade". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chinatown, Chicago. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Chicago/Bridgeport-Chinatown. |

- Chicago Chinese American Historical Society

- Chinese–American Museum of Chicago

- Chicago Chinatown Chamber of Commerce

- John C. Haines Elementary School - K-8 school of Chicago's Chinatown