China–India relations

| |

India |

China |

|---|---|

China–India relations, also called Sino-Indian relations or Indo-China relations, refers to the bilateral relationship between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of India. The modern relationship began in 1950 when India was among the first countries to end formal ties with the Republic of China (Taiwan) and recognize the PRC as the legitimate government of Mainland China. China and India are the two most populous countries and fastest growing major economies in the world. Growth in diplomatic and economic influence has increased the significance of their bilateral relationship. Currently, ties between the two nuclear armed countries have severely deteriorated due to a military standoff in Bhutan.[1]

Cultural and economic relations between China and India date back to ancient times. The Silk Road not only served as a major trade route between India and China, but is also credited for facilitating the spread of Buddhism from India to East Asia.[2] During the 19th century, China's growing opium trade with the East India Company triggered the First and Second Opium Wars.[3][4] During World War II, India and China both played a crucial role in halting the progress of Imperial Japan.[5]

Relations between contemporary China and India have been characterised by border disputes, resulting in three military conflicts — the Sino-Indian War of 1962, the Chola incident in 1967, and the 1987 Sino-Indian skirmish.[6] However, since the late 1980s, both countries have successfully rebuilt diplomatic and economic ties. In 2008, China became India's largest trading partner and the two countries have also extended their strategic and military relations.[7][8][9]

Despite growing economic and strategic ties, there are several hurdles for India and the PRC to overcome. India faces trade imbalance heavily in favour of China. The two countries failed to resolve their border dispute and Indian media outlets have repeatedly reported Chinese military incursions into Indian territory.[10] Both countries have steadily established military infrastructure along border areas.[10][11] Additionally, India remains wary about China's strong strategic bilateral relations with Pakistan,[12] while China has expressed concerns about Indian military and economic activities in the disputed South China Sea.[13]

In June 2012, China stated its position that "Sino-Indian ties" could be the most "important bilateral partnership of the century".[14] However, India did not respond that initiative from China in equal terms, as Indian media often displayed a noisy and belligerent stand against China.[15] That month Wen Jiabao, the Premier of China and Manmohan Singh, the Prime Minister of India set a goal to increase bilateral trade between the two countries to US$100 billion by 2015.[16] In November 2012, the bilateral trade was estimated to be $73.9 billion.[17]

According to a 2014 BBC World Service Poll, 33% of Indians view China positively, with 35% expressing a negative view, whereas 27% of Chinese people view India positively, with 35% expressing a negative view.[18] A 2014 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center showed 72% of Indians were concerned that territorial disputes between China and neighbouring countries could lead to a military conflict.[19]

The President of the People's Republic of China, Xi Jinping, was one of the top world leaders to visit New Delhi after Narendra Modi took over as Prime Minister of India in 2014.[20] India's insistence to raise South China Sea in various multilateral forums subsequently did not help that beginning once again, the relationship facing suspicion from Indian administration and media alike.[21]

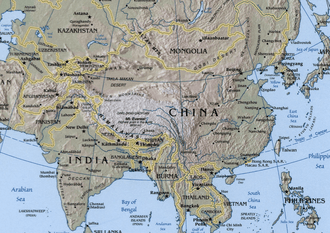

Geographical overview

(The border between the People's Republic of China and the Republic of India over Arunachal Pradesh/South Tibet reflects actual control, without dotted line showing claims.)

China and India are separated by the Himalayas. China and India today share a border with Nepal and Bhutan acting as buffer states. Parts of the disputed Kashmir region claimed by India are claimed and administered by either Pakistan (Azad Kashmir and Gilgit and Baltistan) or by the PRC (Aksai Chin). The Government of Pakistan on its maps shows the Aksai Chin area as mostly within China and labels the boundary "Frontier Undefined" while India holds that Aksai Chin is illegally occupied by the PRC.

China and India also dispute most of Arunachal Pradesh. However, both countries have agreed to respect the Line of Actual Control.

Country comparison

| |

| |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

1,337,364,960[22] |

1,386,301,390[23] |

| Area | 3,287,240 km² (1,269,210 sq mi) | 9,640,821 km² (3,704,427 sq mi) |

| Population density | 452/km²[22] | 148/km²[23] |

| Capital | New Delhi | Beijing |

| Largest city | Mumbai | Shanghai |

| Government | Federal republic, parliamentary democracy | Socialist, one-party state |

| First leader | Jawaharlal Nehru | Mao Zedong |

| Current leader | Narendra Modi | Xi Jinping |

| Official languages | Hindi, English, Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Malayalam, Marathi, Meitei, Nepali, Odia, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, Maithili, Dogri, Santali, Bodo and Urdu (See Languages with official status in India) | Standard Chinese (Mandarin), Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur, Zhuang (See Languages of China) |

| Main religions | Hinduism (79.8%), Islam (14.2%), Christianity (2.5%), Sikhism (1.9%) Buddhism (0.8%), Jainism (0.4%) other religions (0.6%)[24] see also Religion in India | >10% each: non-religious, folk religions and Taoism, Buddhism. <10% each: Islam, Christianity, Bon. See also Religion in China |

| GDP (nominal) (2016) | US$2.45 trillion | US$11.22 trillion |

| GDP (nominal) per capita (2016) | US$1,850 | US$8,113 |

| GDP (PPP) (2016) | US$9.49 trillion | US$21.26 trillion |

| GDP (PPP) per capita (2016) | US$7,153 | US$15,424 |

| Human Development Index (2015) | 0.624 (medium) | 0.738 (high) |

| Foreign exchange reserves (Sept 2016) | US$386,539 million | US$3,185,916 million |

| Military expenditures | US$45.785 billion (2.5% of GDP) | US$166.107 billion (2012) (2.0% of GDP) |

| Manpower | Active troops: 1,325,000 (2,142,821 reserve personnel) | Active troops: approximately 2,285,000 (800,000 reserve personnel) |

Early history

Hinduism

Hinduism is practiced by a minority of residents of China. The religion itself has a very limited presence in modern mainland China, but archaeological evidence suggests the presence of Hinduism in different provinces of medieval China.[25] Hindu influences were also absorbed in the country through the spread of Buddhism over its history.[26] Practices originating in the Vedic tradition of ancient India such as yoga and meditation are also popular in China.Hindu community, particularly through Tamil merchant guilds of Ayyavole and Manigramam, once thrived in medieval South China;[27][28] evidence of Hindu motifs and temples, such as in the Kaiyuan Temple, continue to be discovered in Quanzhou, Fujian province of southeast China.[29] A small community of Hindu immigrant workers exists in Hong Kong.Tamil Hindu Indian merchants traded in Quanzhou during the Yuan dynasty.[30][31][32][33] Hindu statues were found in Quanzhou dating to this period.[34]

Buddhism

Buddhism shaped Chinese culture in a wide variety of areas including art, politics, literature, philosophy, medicine, and material culture.Buddhism entered Han China via the Silk Road, beginning in the 1st or 2nd century CE.[35][36] The first documented translation efforts by Buddhist monks in China (all foreigners) were in the 2nd century CE, possibly as a consequence of the expansion of the Buddhist Kushan Empire into the Chinese territory of the Tarim Basin.[37] Bodhidharma was a Buddhist monk traditionally credited as the transmitter of Chan Buddhism to China, and regarded as its first Chinese patriarch.During the early period of Chinese Buddhism, the Indian early Buddhist schools recognized as important, and whose texts were studied, were the Dharmaguptakas, Mahīśāsakas, Kāśyapīyas, Sarvāstivādins, and the Mahāsāṃghikas.[38]

Bodhidharma was an Indian Buddhist monk who lived during the 5th or 6th century. He is traditionally credited as the transmitter of Chan Buddhism to China, and regarded as its first Chinese patriarch. According to Chinese legend, he also began the physical training of the monks of Shaolin Monastery that led to the creation of Shaolin kungfu. In Japan, he is known as Daruma

Astronomy and mathematics

Indian astronomy reached China with the expansion of Buddhism during the Later Han (25–220 CE).[39] Further translation of Indian works on astronomy was completed in China by the Three Kingdoms era (220–265 CE).[39] However, the most detailed incorporation of Indian astronomy occurred only during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) when a number of Chinese scholars—such as Yi Xing— were versed both in Indian and Chinese astronomy.[39] A system of Indian astronomy was recorded in China as Jiuzhi-li (718 CE), the author of which was an Indian by the name of Qutan Xida—a translation of Devanagari Gotama Siddha—the director of the Tang dynasty's national astronomical observatory.[39]During the 8th century, the astronomical table of sines by the Indian astronomer and mathematician, Aryabhatta (476-550), were translated into the Chinese astronomical and mathematical book of the Treatise on Astrology of the Kaiyuan Era (Kaiyuan Zhanjing), compiled in 718 CE during the Tang Dynasty.[40] The Kaiyuan Zhanjing was compiled by Gautama Siddha, an astronomer and astrologer born in Chang'an, and whose family was originally from India. He was also notable for his translation of the Navagraha calendar into Chinese.[41] Gautama Siddha introduced Indian numerals with zero (〇) in 718 in China as a replacement of counting rods.[42][43] In 3rd-century C.E, the Matanaga avadha was translated into Chinese.although the original is believed to date earlier. It gives the lengths of monthly shadows of a 12-inch gnomon, which is the standard parameter of Indian astronomy.The work also mentions the 28 Indian nakshatras.[44][45] In the beginning of the second century, Sardulakarnavadana was translated into Chinese several times, This work contains the usual Sanskrit names of the 28 nakshatras. starting with krttika.[46] [45]From the 1st century onward Lalitavistara was translated into Chinese several times. It is in this work that the famous Buddhist centesimal-scale counting occurs during the dialogue between Prince Gautamaand and the mathematician Arjuna. The first series of counts ends with tallaksana (= 1053), beyond which eight more ganana series are mentioned.Atomic-scale counting is also mentioned[47][45].The Mahaprajnaparamita Sastra (of Nagarjuna, second century) was translated into Chinese by Kumarajiva in the early fifth century.16 The astronomical parameters mentioned in this translation are comparable to those given in the Vedanga Jyotisha.Indian system of numeration appeared in the Chinese work Ta PaoChi Ching (Maharatnakuta Sutra), translated by Upasunya (in 541 c.e.)[48][45] The Chinese translations of the following works are mentioned in the Sui Shu, or Official History of the Sui Dynasty (seventh century):

- Po-lo-men Thien Wen Ching (Brahminical Astronomical Classic) in 21 books.

- Po-lo-men Chieh-Chhieh Hsien-jen Thien Wen Shuo (Astronomical Theories of

Brahman.a Chieh-Chhieh Hsienjen) in 30 books.

- Po-lo-men Thien Ching (Brahminical Heavenly Theory) in one book.

- Mo-teng-Chia Ching Huang-thu (Map of Heaven in the Matangi Sutra) in one

book.

- Po-lo-men Suan Ching (Brahminical Arithmetical Classic) in three books.

- Po-lo-men Suan Fa (Brahminical Arithmetical Rules) in one book.

- Po-lo-men Ying Yang Suan Ching (Brahminical Method of Calculating Time)

Although these translations are lost, they were also mentioned in other sources.[49][45]

Martial arts

Indian martial arts may have spread to China via the transmission of Buddhism in the early 5th or 6th centuries of the common era and thus influenced Shaolin Kungfu. Elements from Indian philosophy, like the Nāga, Rakshasa, and the fierce Yaksha were syncretized into protectors of Dharma; these mythical figures from the Dharmic religions figure prominently in Shaolinquan, Chang quan and staff fighting.[50] The religious figures from Dharmic religions also figure in the movement and fighting techniques of Chinese martial arts.[51] Various styles of kung fu are known to contain movements that are identical to the Mudra hand positions used in Hinduism and Buddhism, both of which derived from India.[52] Similarly, the 108 pressure points in Chinese martial arts are believed by some to be based on the marmam points of Indian varmakalai.[53][54]

The predominant telling of the diffusion of the martial arts from India to China involves a 5th-century prince turned into a monk named Bodhidharma who is said to have traveled to Shaolin, sharing his own style and thus creating Shaolinquan.[55] According to Wong Kiew Kit, the Monk's creation of Shaolin arts "...marked a watershed in the history of kungfu, because it led to a change of course, as kungfu became institutionalized. Before this, martial arts were known only in general sense."[56]

The association of Bodhidharma with martial arts is attributed to Bodhidharma's own Yi Jin Jing, though its authorship has been disputed by several modern historians such as Tang Hao,[57] Xu Zhen and Matsuda Ryuchi.[58] The oldest known available copy of the Yi Jin Jing was published in 1827[58] and the composition of the text itself has been dated to 1624. According to Matsuda, none of the contemporary texts written about the Shaolin martial arts before the 19th century, such as Cheng Zongyou's Exposition of the Original Shaolin Staff Method or Zhang Kongzhao's Boxing Classic: Essential Boxing Methods, mention Bodhidharma or credit him with the creation of the Shaolin martial arts. The association of Bodhidharma with the martial arts only became widespread after the 1904–1907 serialization of the novel The Travels of Lao Ts'an in Illustrated Fiction Magazine.[59]

The discovery of arms caches in the monasteries of Chang'an during government raids in 446 AD suggests that Chinese monks practiced martial arts prior to the establishment of the Shaolin Monastery in 497.[60] Moreover, Chinese monasteries, not unlike those of Europe, in many ways were effectively large landed estates, that is, sources of considerable wealth which required protection that had to be supplied by the monasteries' own manpower.[60]

Antiquity

The first records of contact between China and India were written during the 2nd century BCE. Buddhism was transmitted from India to China in the 1st century CE.[62] Trade relations via the Silk Road acted as economic contact between the two regions.

China and India have also had some contact before the transmission of Buddhism. References to a people called the Chinas, are found in ancient Indian literature. The Indian epic Mahabharata (c. 5th century BCE) contains references to "China", which may have been referring to the Qin state which later became the Qin Dynasty. Chanakya (c. 350-283 BCE), the prime minister of the Maurya Empire refers to Chinese silk as "cinamsuka" (Chinese silk dress) and "cinapatta" (Chinese silk bundle) in his Arthashastra.

In the Records of the Grand Historian, Zhang Qian (d. 113 BCE) and Sima Qian (145-90 BCE) make references to "Shendu", which may have been referring to the Indus Valley (the Sindh province in modern Pakistan), originally known as "Sindhu" in Sanskrit. When Yunnan was annexed by the Han Dynasty in the 1st century, Chinese authorities reported an Indian "Shendu" community living there.[63]

Middle Ages

From the 1st century onwards, many Indian scholars and monks travelled to China, such as Batuo (fl. 464-495 CE)—first abbot of the Shaolin Monastery—and Bodhidharma—founder of Chan/Zen Buddhism—while many Chinese scholars and monks also travelled to India, such as Xuanzang (b. 604) and I Ching (635-713), both of whom were students at Nalanda University in Bihar. Xuanzang wrote the Great Tang Records on the Western Regions, an account of his journey to India, which later inspired Wu Cheng'en's Ming Dynasty novel Journey to the West, one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature. According to some, St. Thomas the Apostle travelled from India to China and back (see Perumalil, A.C. The Apostle in India. Patna, 1971: 5-54.)

Tamil dynasties

The Cholas maintained good relationship with the Chinese. Arrays of ancient Chinese coins have been found in the Cholas homeland (i.e. Thanjavur, Tiruvarur and Pudukkottai districts of Tamil Nadu, India).[64]

Under Rajaraja Chola and his son Rajendra Chola, the Cholas had strong trading links with Chinese Song Dynasty.[65][66][67] The Chola navy conquered the Sri Vijaya Empire of Indonesia and Malaysia and secured a sea trading route to China.[65]

Many sources describe Bodhidharma, the founder of the Zen school of Buddhism in China, as a prince of the Pallava dynasty.[68]

Tang and Harsha dynasties

During the 7th century, Tang dynasty China gained control over large portions of the Silk Road and Central Asia. Wang Xuance had sent a diplomatic mission to northern India, which was embroiled by civil war just following the death of Emperor Harsha (590–647). After the murder of 30 members of this mission by the usurper claimants, Wang fled, and returned with allied Nepali and Tibetan troops to back the opposition. With his forces, Wang captured the capital, while his deputy Jiang Shiren (蒋师仁) captured the usurper and sent him back to Emperor Taizong (599-649) in Chang'an as a prisoner.

During the 8th century, the astronomical table of sines by the Indian astronomer and mathematician, Aryabhatta (476-550), were translated into the Chinese astronomical and mathematical book of the Treatise on Astrology of the Kaiyuan Era (Kaiyuan Zhanjing), compiled in 718 CE during the Tang Dynasty.[40] The Kaiyuan Zhanjing was compiled by Gautama Siddha, an astronomer and astrologer born in Chang'an, and whose family was originally from India. He was also notable for his translation of the Navagraha calendar into Chinese.

Yuan dynasty

A rich merchant from the Ma'bar Sultanate, Abu Ali (P'aehali) 孛哈里 (or 布哈爾 Buhaer), was associated closely with the Ma'bar royal family. After a fallout with the Ma'bar family, he moved to Yuan dynasty China and received a Korean woman as his wife and a job from the Emperor, the woman was formerly 桑哥 Sangha's wife and her father was 蔡仁揆 채송년 Ch'ae In'gyu during the reign of 忠烈 Chungnyeol of Goryeo, recorded in the Dongguk Tonggam, Goryeosa and 留夢炎 Liu Mengyan's 中俺集 Zhong'anji.[69][70][71] 桑哥 Sangha was a Tibetan.[72] Tamil Hindu Indian merchants traded in Quanzhou during the Yuan dynasty.[73][74][75][76][77] Hindu statues were found in Quanzhou dating to this period.[78]

Ming dynasty

Between 1405 and 1433, Ming dynasty China sponsored a series of seven naval expeditions led by Admiral Zheng He. Zheng He visited numerous Indian kingdoms and ports, including India, Bengal, and Ceylon, Persian Gulf, Arabia, and later expeditions ventured down as far as Malindi in what is now Kenya. Throughout his travels, Zheng He liberally dispensed Chinese gifts of silk, porcelain, and other goods. In return, he received rich and unusual presents, including African zebras and giraffes. Zheng He and his company paid respect to local deities and customs, and in Ceylon they erected a monument (Galle Trilingual Inscription) honouring Buddha, Allah, and Vishnu.

Sino-Sikh War

In the 18th to 19th centuries, the Sikh Confederacy expanded into neighbouring lands. It had annexed Ladakh into the state of Jammu in 1834. In 1841, they invaded Tibet and overran parts of western Tibet. Chinese forces defeated the Sikh army in December 1841, forcing the Sikh army to withdraw, and in turn entered Ladakh and besieged Leh, where they were in turn defeated by the Sikh Army. At this point, neither side wished to continue the conflict. The Sikhs claimed victory. as the Sikhs were embroiled in tensions with the British that would lead up to the First Anglo-Sikh War, while the Chinese was in the midst of the First Opium War. The two parties signed a treaty in September 1842, which stipulated no transgressions or interference in the other country's frontiers.[79]

British India

The British East India Company used opium grown in India as export to China. Britain used their Indian sepoys and the British Indian Army in the Opium Wars and Boxer Rebellion against China. The British used Indian soldiers to guard the Foreign concessions in areas like Shanghai. The Chinese slur "Yindu A San" (Indian number three) was used to describe Indian soldiers in British service.

After independence

On 1 October 1949 the People’s Liberation Army defeated the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party). On 15 August 1947, India became an independent British dominion and became a federal, democratic republic after its constitution came into effect on 26 January 1950.

Jawaharlal Nehru based his vision of "resurgent Asia" on friendship between the two largest states of Asia; his vision of an internationalist foreign policy governed by the ethics of the Panchsheel (Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence), which he initially believed was shared by China. Nehru was disappointed when it became clear that the two countries had a conflict of interest in Tibet, which had traditionally served as a buffer zone, and where India believed it had inherited special privileges from the British Raj.

1950s

India established diplomatic relations with the PRC on 1 January 1950, the second non-communist nation to do so.

Mao Zedong viewed Tibet as an integral part of the People's Republic of China. Mao saw Indian concern over Tibet as a manifestation of interference in the internal affairs of the PRC. The PRC reasserted control over Tibet and to end Lamaism (Tibetan Buddhism) and feudalism, which it did by force of arms in 1950. To avoid antagonizing the PRC, Nehru informed Chinese leaders that India had no political ambitions, territorial ambitions, nor did it seek special privileges in Tibet, but that traditional trading rights must continue. With Indian support, Tibetan delegates signed an agreement in May 1951 recognizing PRC sovereignty but guaranteeing that the existing political and social system of Tibet would continue..

In April 1954, India and the PRC signed an eight-year agreement on Tibet that became the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence (or Panchsheel). Although critics called the Panchsheel naive, Nehru calculated that India's best guarantee of security was to establish a psychological buffer zone in place of the lost physical buffer of Tibet.

It is the popular perception that the catch phrase of India's diplomacy with China in the 1950s was Hindi-Chini bhai-bhai, which means, in Hindi, "Indians and Chinese are brothers" While VK Krishna Menon was the Defence Minister in 1958, Nehru had privately told G. Parthasarathi the Indian envoy to China to send all communications directly to him bypassing Menon, due to his communist background and sympathy towards China.[80]

Nehru sought to initiate a more direct dialogue between the peoples of China and India in culture and literature. Around that time, the famous Indian artist (painter) Beohar Rammanohar Sinha, who had earlier decorated the pages of the original Constitution of India, was sent to China in 1957 on a Government of India fellowship to establish a direct cross-cultural and inter-civilization bridge. Noted Indian scholar Rahul Sankrityayan and diplomat Natwar Singh were also there, and Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan paid a visit to PRC. Between 1957 and 1959, Beohar Rammanohar Sinha not only disseminated Indian art in PRC but also became skilled in Chinese painting and lacquer-work. He also spent time with great masters Qi Baishi, Li Keran, Li Kuchan as well as some moments with Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. Consequently, up until 1959, despite border skirmishes, Chinese leaders amicably had assured India that there was no territorial controversy.[81]

In 1954, India published new maps that included the Aksai Chin region within the boundaries of India.[82] When India discovered that China built a road through the region, border clashes and Indian protests became more frequent. In January 1959, PRC premier Zhou Enlai wrote to Nehru, pointing out that no government in China had accepted as legal the McMahon Line, which in the 1914 Simla Convention defined the eastern section of the border between India and Tibet.

In March 1959, the Dalai Lama, spiritual and temporal head of the Tibetan people, sought sanctuary in Dharmsala, Himachal Pradesh. Thousands of Tibetan refugees settled in northwestern India. The PRC accused India of expansionism and imperialism in Tibet and throughout the Himalayan region. China claimed 104,000 km² of territory over which India's maps showed clear sovereignty, and demanded "rectification" of the entire border.

1960s

Sino-Indian War

Border disputes resulted in a short border war between the People's Republic of China and India on 20 October 1962. The border clash resulted in a defeat of India as the PRC pushed the Indian forces to within forty-eight kilometres of the Assam plains in the northeast and occupied strategic points in Ladakh, until the PRC declared a unilateral cease-fire on 21 November and withdrew twenty kilometers behind its contended line of control.

At the time of Sino-Indian border conflict, the Communist Party of India was accused by the Indian government as being pro-PRC, and a large number of political leaders were jailed. Subsequently, CPI split with the leftist section forming the Communist Party of India (Marxist) in 1964. CPI(M) held some contacts with the Communist Party of China in the initial period after the split, but did not fully embrace the political line of Mao Zedong.

Relations between the PRC and India deteriorated during the rest of the 1960s and the early 1970s as China–Pakistan relations improved and Sino-Soviet relations worsened. The PRC backed Pakistan in its 1965 war with India. Between 1967 and 1971, an all-weather road was built across territory claimed by India, linking PRC's Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region with Pakistan; India could do no more than protest.

The PRC continued an active propaganda campaign against India and supplied ideological, financial, and other assistance to dissident groups, especially to tribes in northeastern India. The PRC accused India of assisting the Khampa rebels in Tibet.

Sri Lanka played the role of chief negotiator to withdraw the Chinese troops from the Indian territory. Both countries agreed to Colombo's proposals.[83]

Later conflicts

In late 1967, there were two more conflicts between Indian and Chinese forces at their contested border, in Sikkim. The first conflict was dubbed the "Nathu La Incident", and the other the "Cho La Incident".

In September 1967, Chinese and Indian forces clashed at Nathu La. On 11 September, Chinese troops opened fire on a detachment of Indian soldiers tasked with protecting an engineering company that was fencing the North Shoulder of Nathu La. This escalated over the next five days to an exchange of heavy artillery and mortar fire between the Indian and Chinese forces. Sixty-two Indian soldiers were killed.[84]

Soon afterwards, Indian and Chinese forces clashed again in the Chola incident. On 1 October 1967, some Indian and Chinese soldiers had an argument over the control of a boulder at the Chola outpost in Sikkim (then a protectorate of India), triggering a fight that escalated to a mortar and heavy machine gun duel.[85] On 10 October, both sides again exchanged heavy fire. While Indian forces would sustain eighty-eight troops killed in action with another 163 troops wounded, China would suffer greater casualties, with 300 killed and 450 wounded in Nathu La, as well as forty in Chola.[86]

1970s

In August 1971, India signed its Treaty of Peace, Friendship, and Co-operation with the Soviet Union. The PRC sided with Pakistan in its December 1971 war with India. Although China strongly condemned India, it did not carry out its veiled threat to intervene on Pakistan's behalf. By this time, the PRC had replaced the Republic of China in the UN where its representatives denounced India as being a "tool of Soviet expansionism."

India and the PRC renewed efforts to improve relations after Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's Congress party lost the 1977 elections to Morarji Desai's Janata Party. In 1978, the Indian Minister of External Affairs Atal Bihari Vajpayee made a landmark visit to Beijing, and both countries officially re-established diplomatic relations in 1979. The PRC modified its pro-Pakistan stand on Kashmir and appeared willing to remain silent on India's absorption of Sikkim and its special advisory relationship with Bhutan. The PRC's leaders agreed to discuss the boundary issue, India's priority, as the first step to a broadening of relations. The two countries hosted each other's news agencies, and Mount Kailash and Mansarowar Lake in Tibet, the mythological home of the Hindu pantheon, were opened to annual pilgrimages.

1980s

In 1981, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China, Huang Hua made a landmark visit to New Delhi.[87] PRC Premier Zhao Ziyang concurrently toured Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh.

In 1980, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi approved a plan to upgrade the deployment of forces around the Line of Actual Control. India also undertook infrastructural development in disputed areas.[88][89]

In 1984, squads of Indian soldiers began actively patrolling the Sumdorong Chu Valley in Arunachal Pradesh. In the winter of 1986, the Chinese deployed their troops to the Sumdorong Chu before the Indian team could arrive and built a Helipad at Wandung.[90] Surprised by the Chinese occupation, India's then Chief of Army Staff, General K.Sundarji, airlifted a brigade to the region.[89][91]

Chinese troops could not move any further into the valley and were forced to away from the valley.[92] By 1987, Beijing's reaction was similar to that in 1962 and this prompted many Western diplomats to predict war. However, Indian foreign minister N.D. Tiwari and Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi travelled to Beijing to negotiate a mutual de-escalation.[89]

India and the PRC held eight rounds of border negotiations between December 1981 and November 1987. In 1985 the PRC insisted on mutual concessions without defining the exact terms of its "package proposal" or where the actual line of control lay. In 1986 and 1987, the negotiations achieved nothing, given the charges exchanged between the two countries of military encroachment in the Sumdorung Chu Valley. China's construction of a military post and helicopter pad in the area in 1986 and India's grant of statehood to Arunachal Pradesh (formerly the North-East Frontier Agency) in February 1987 caused both sides to deploy troops to the area. The PRC relayed warnings that it would "teach India a lesson" if it did not cease "nibbling" at Chinese territory. By the summer of 1987, however, both sides had backed away from conflict and denied military clashes had taken place.

A warming trend in relations was facilitated by Rajiv Gandhi's visit to China in December 1988. The two sides issued a joint communiqué that stressed the need to restore friendly relations on the basis of the Panchsheel. India and the People's Republic of China agreed to achieve a "fair and reasonable settlement while seeking a mutually acceptable solution" to the border dispute. The communiqué also expressed China's concern about agitation by Tibetan separatists in India and reiterated that anti-China political activities by expatriate Tibetans would not be tolerated. Rajiv Gandhi signed bilateral agreements on science and technology co-operation, establish direct air links, and on cultural exchanges. The two sides also agreed to hold annual diplomatic consultations between foreign ministers, set up a joint committee on economic and scientific co-operation, and a joint working group on the boundary issue. The latter group was to be led by the Indian foreign secretary and the Chinese vice minister of foreign affairs.

1990s

Top-level dialogue continued with the December 1991 visit of PRC premier Li Peng to India and the May 1992 visit to China of Indian president R. Venkataraman. Six rounds of talks of the Indian-Chinese Joint Working Group on the Border Issue were held between December 1988 and June 1993. Progress was also made in reducing tensions on the border via mutual troop reductions, regular meetings of local military commanders, and advance notification about military exercises. In July 1992, Sharad Pawar visited Beijing, the first Indian Minister of Defence to do so. Consulates reopened in Bombay (Mumbai) and Shanghai in December 1992. During

In 1993, The sixth-round of the joint working group talks was held in New Delhi but resulted in only minor developments. Prime Minister Narasimha Rao and Premier Li Peng signed a border agreement dealing with cross-border trade, cooperation on environmental issues (e.g. Pollution, Animal extinction, Global Warming, etc.) and radio and television broadcasting. A senior-level Chinese military delegation made a goodwill visit to India in December 1993 aimed at "fostering confidence-building measures between the defence forces of the two countries." The visit, however, came at a time when China was providing greater military support to Burma. The presence of Chinese radar technicians in Burma's Coco Islands, which border India's Andaman and Nicobar Islands caused concern in India.

In January 1994, Beijing announced that it not only favored a negotiated solution on Kashmir, but also opposed any form of independence for the region. Talks were held in New Delhi in February aimed at confirming established "confidence-building measures", discussing clarification of the "line of actual control", reduction of armed forces along the line, and prior information about forthcoming military exercises. China's hope for settlement of the boundary issue was reiterated.

In 1995, talks by the India-China Expert Group led to an agreement to set up two additional points of contact along the 4,000 km border to facilitate meetings between military personnel. The two sides were reportedly "seriously engaged" in defining the McMahon Line and the line of actual control vis-à-vis military exercises and prevention of air intrusion. Talks were held in Beijing in July and in New Delhi in August to improve border security, combat cross-border crimes and on additional troop withdrawals from the border. These talks further reduced tensions.

There was little notice taken in Beijing of the April 1995 announcement of the opening of the Taipei Economic and Cultural Centre in New Delhi. The Centre serves as the representative office of the Republic of China (Taiwan) and is the counterpart of the India-Taipei Association located in Taiwan. Both institutions share the goal of improving India-ROC relations, which have been strained since New Delhi's recognition of Beijing in 1950.

Sino-Indian relations hit a low point in 1998 following India's nuclear tests. Indian Defence Minister George Fernandes declared that "“in my perception of national security, China is enemy No 1.…and any person who is concerned about India’s security must agree with that fact",[93] hinting that India developed nuclear weapons in defence against China's nuclear arsenal. In 1998, China was one of the strongest international critics of India's nuclear tests and entry into the nuclear club. During the 1999 Kargil War China voiced support for Pakistan, but also counseled Pakistan to withdraw its forces.

2000s

In a major embarrassment for China, the 17th Karmapa, Urgyen Trinley Dorje, who was proclaimed by China, made a dramatic escape from Tibet to the Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim. Chinese officials were in a quandary on this issue as any protest to India on the issue would mean an explicit endorsement on India's governance of Sikkim, which the Chinese still hadn't recognised. In 2003, China officially recognised Indian sovereignty over Sikkim as the two countries moved towards resolving their border disputes.

In 2004, the two countries proposed opening up the Nathula and Jelepla Passes in Sikkim. 2004 was a milestone in Sino-Indian bilateral trade, surpassing the US$10 billion mark for the first time. In April 2005, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao visited Bangalore to push for increased Sino-Indian cooperation in high-tech industries. Wen stated that the 21st century will be "the Asian century of the IT industry."Regarding the issue of India gaining a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, Wen Jiabao initially seemed to support the idea, but had returned to a neutral position.

In the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) Summit in 2005, China was granted an observer status. While other countries in the region are ready to consider China for permanent membership in the SAARC, India seemed reluctant.

Issues surrounding energy has risen in significance. Both countries have growing energy demand to support economic growth. Both countries signed an agreement in 2006 to envisage ONGC Videsh Ltd (OVL) and the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) to placing joint bids for promising projects.

In 2006, China and India re-opened Nathula pass for trading. Nathula was closed 44 years prior to 2006. Re-opening of border trade will help ease the economic isolation of the region.[94] In November 2006, China and India had a verbal spat over claim of the north-east Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. India claimed that China was occupying 38,000 square kilometres of its territory in Kashmir, while China claimed the whole of Arunachal Pradesh as its own.[95]

In 2007, China denied the application for visa from an Indian Administrative Service officer in Arunachal Pradesh. According to China, since Arunachal Pradesh is a territory of China, he would not need a visa to visit his own country.[96] Later in December 2007, China reversed its policy by granting a visa to Marpe Sora, an Arunachal born professor in computer science.[97][98] In January 2008, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh visited China to discuss trade, commerce, defence, military, and various other issues.

Until 2008 the British Government's position remained the same as had been since the Simla Accord of 1913: that China held suzerainty over Tibet but not sovereignty. Britain revised this view on 29 October 2008, when it recognized Chinese sovereignty over Tibet through its website.[99][100][101] The Economist stated that although the British Foreign Office's website does not use the word sovereignty, officials at the Foreign Office said "it means that, as far as Britain is concerned, 'Tibet is part of China. Full stop.'"[102] This change in Britain's position affects India's claim to its North Eastern territories which rely on the same Simla Accord that Britain's prior position on Tibet's sovereignty was based upon.[103]

In October 2009, Asian Development Bank formally acknowledging Arunachal Pradesh as part of India, approved a loan to India for a development project there. Earlier China had exercised pressure on the bank to cease the loan,[104] however India succeeded in securing the loan with the help of the United States and Japan. China expressed displeasure at ADB.[105][106]

2010s

Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao paid an official visit to India from 15–17 December 2010 at the invitation of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.[107] He was accompanied by 400 Chinese business leaders, who wished to sign business deals with Indian companies.[108]

| “ | India and China are two very populous countries with ancient civilisations, friendship between the two countries has a time-honoured history, which can be dated back 2,000 years, and since the establishment of diplomatic ties between our two countries, in particular the last ten years, friendship and cooperation has made significant progress.[109] |

” |

In April 2011, during the BRICS summit in Sanya, Hainan, China[110] the two countries agreed to restore defence co-operation and China had hinted that it may reverse its policy of administering stapled visas to residents of Jammu and Kashmir.[111][112] This practice was later stopped,[113] and as a result, defence ties were resumed between the two countries and joint military drills were expected.

It was reported in February 2012 that India will reach US$100 billion trade with China by 2015.[114] Bilateral trade between the two countries reached US$73 billion in 2011, making China India's largest trade partner, but slipped to US$66 billion in 2012.[115]

In the 2012 BRICS summit in New Delhi, India, Chinese President Hu Jintao told Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh that "it is China's unswerving policy to develop Sino-Indian friendship, deepen strategic cooperation and seek common development" and "China hopes to see a peaceful, prosperous and continually developing India and is committed to building more dynamic China-India relationship".[116] Other topics were discussed, including border dispute problems and a unified BRICS central bank.

In response to India's test of an Agni-V missile capable of carrying a nuclear warhead to Beijing, the PRC called for the two countries to "cherish the hard-earned momentum of co-operation".[117]

A three-week standoff between Indian and Chinese troops in close proximity to each other and the Line of Actual Control between Jammu and Kashmir's Ladakh region and Aksai Chin was defused on 5 May 2013,[118] days before a trip by Indian Foreign Minister Salman Khurshid to China; Khurshid said that both countries had a shared interest in not having the border issue exacerbate or "destroy" long-term progress in relations. The Chinese agreed to withdraw their troops in exchange for an Indian agreement to demolish several "live-in bunkers" 250 km to the south in the disputed Chumar sector.[119]

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang made his first foreign visit to India on 18 May 2013 in a bid to increase diplomatic co-operation, to cement trade relations, and formulate border dispute solutions.[120][121]

Indian President Pranab Mukherjee’s visit to Arunachal Pradesh, a northeast Indian state that China recognizes as "South Tibet", in late November, 2013 and in his speech calling the area an "integral and important part of India" generated an angry response from Beijing.[122] Foreign ministry spokesman Qin Gang's statement in response to Mukherjee's two-day visit to Arunachal Pradesh was "China's stance on the disputed area on the eastern part of the China-India border is consistent and clear.[123]

In September, 2014 the relationship took a sting as troops of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) have reportedly entered two kilometres inside the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Chumar sector.[124] The next month, V. K. Singh said that China and India had come to a "convergence of views" on the threat of terrorism emanating from Pakistan.[125]

In more modern times, China and India have been working together to produce films together, such as Kung Fu Yoga starring Jackie Chan.[126] However, disruptions have risen again due to China building trade routes with Pakistan on disputed Kashmir territory.[127]

2017 Doklam standoff

With the 1890 Convention of Calcutta, British India and China established the China-Sikkim boundary.[128] This Convention [129] states that the Sikkim-China border begins at Mount Gipmochi. India agreed with the China-Sikkim boundary, and stated there was no dispute.[130] Later, India and Bhutan considered Batang La to be the tri-junction point [129] and Bhutan was not part of the 1890 treaty. [131] Bhutan didn’t produce maps on its own until 1961, when the Survey of India helped Bhutan to create one.[129] The Chinese foreign minister has claimed that China has always controlled the plateau at Doklam.[132]

Since 1980s, about 24 rounds of boundary talks have been held between China and Bhutan, and basic consensus on the boundary has been established.[130] The China Foreign Ministry claimed in 2017 that both parties had informally agreed that Doklam belongs to China.[133]Analysts in New Delhi said that Bhutan was not part of the 1890 treaty, dispute was between China and Bhutan. [131]

On 18 June 2017, the Indian Army crossed the border at Doka La (on the west side of Doklam) to stop the construction of a road by the People's Liberation Army of China in the Doklam sector.[130] On 19 June 2017, China urged India to immediately withdraw its border guards.[130][134][135] China claims that the Indian side 'justified' its incursion under the cloak of 'protecting Bhutan', and attempted to create a dispute in the Doklam area to prevent and contain border negotiations between China and Bhutan.[136] The ongoing standoff between Indian and Chinese armies has lasted longer than any other standoff between the two parties since 1962.[137] Weeks after the Indian Army crossed the border, on June 28 2017, Bhutan issued with a demarche demanding China to cease road building in Doklam.[138] According to an opinion-editorial, Bhutanese officials have not asked for involvement or interference by the Indian troops.[139]

The Minister of External Affairs of India Sushma Swaraj said that if China unilaterally changes status-quo of tri-junction point between China-India and Bhutan then it poses a challenge to the security of India. [140] Dr. Manoj Joshi claimed that the tri-junction point cannot be Batang La because India, as the successors of the British, is party to the 1890 convention, though Bhutan is not.[129]

The US expressed concern in mid July 2017.[141][142][143][144] China repeatedly said that India's withdrawal was a prerequisite for meaningful dialogue.[145][146][147] On July 21, 2017, the Minister of External Affairs of India Sushma Swaraj said that for dialogue, both India and China must withdraw troops, i.e. Indian troops withdraw to India, and Chinese troops withdraw from Doklam. Sushma Swaraj also said that the road constructed by China is a threat to Indian security.[148] It's violation of United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3314 to enter territory of another state with an armed force for whatever reason, whether it is political, economic, military or other reasons.[130]

On August 2 2017, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China published a document entitled, 印度边防部队在中印边界锡金段越界 进入中国领土的事实和中国的立场 (Indian border forces cross the border between China and India...The facts...and the position of China), explaining that Indian border forces have illegally crossed the border between China and India and detailing China's position on the matter.[130][149][150] The document says China notified India regarding its plan to construct road in advance. The Ministry of External Affairs of India refused to confirm or deny the statement.[151]

Bilateral trade

China is India's largest trading partner.

Chinese imports from India amounted to $16.4 billion or 0.8% of its overall imports, and 4.2% of India's overall exports in 2014. The 10 major commodities exported from India to the China were:[152][153]

- Cotton: $3.2 billion

- Gems, precious metals, coins: $2.5 billion

- Copper: $2.3 billion

- Ores, slag, ash: $1.3 billion

- Organic chemicals: $1.1 billion

- Salt, sulphur, stone, cement: $958.7 million

- Machines, engines, pumps: $639.7lmillion

- Plastics: $499.7 million

- Electronic equipment: $440 million

- Raw hides excluding furskins: $432.7 million

Chinese exports to India amounted to $58.4 billion or 2.3% of its overall exports, and 12.6% of India's overall imports in 2014. The 10 major commodities exported from China to India were:[153][154]

- Electronic equipment: $16 billion

- Machines, engines, pumps: $9.8 billion

- Organic chemicals: $6.3 billion

- Fertilizers: $2.7 billion

- Iron and steel: $2.3 billion

- Plastics: $1.7 billion

- Iron or steel products: $1.4 billion

- Gems, precious metals, coins: $1.3 billion

- Ships, boats: $1.3 billion

- Medical, technical equipment: $1.2 billion

See also

Sino-Indian relations

- Chindian People of Indo-Chinese Descent

- BRICS – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa

- China in the Mahabharata

- Chindia – China and India together in general, and their economies in particular

- Shanghai Co-operation Organisation

- Bhutan–China relations, Bhutan is India's military ally

- Bhutan–India relations, Bhutan is India's military ally and China's adversary

Border disputes

- Sino-Indian border dispute

- Aksai Chin – controlled by China and claimed by India.

- Arunachal Pradesh – controlled by India and claimed by China. Inhabited by Moinbas, Lhobas (Adi), and Daibameis.

- Doklam

- Tawang District – controlled by India and claimed by China.

- Shaksgam Valley – controlled by China and claimed by India (Conferred to China in 1963 by Pakistan) Trans-Karakoram Tract.

- Bhutan–China border

- Territorial disputes in the South China Sea

- List of territorial disputes

References

- ↑ Shaikh, Mohammed Uzair (15 July 2017). "No Room For Negotiations on Doklam, India Will Face ‘Embarrassment’ if Troops Not Withdrawn: Chinese State Media". India.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ Backus, Maria. Ancient China. Lorenz Educational Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7877-0557-2.

- ↑ Janin, Hunt. The India-China opium trade in the nineteenth century. McFarland, 1999. ISBN 978-0-7864-0715-6.

- ↑ Tansen Sen (January 2003). Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations, 600-1400. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2593-5.

- ↑ Williams, Barbara. World War Two. Twenty-First Century Books, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8225-0138-1.

- ↑ "http://www.apcss.org/core/BIOS/malik/India-China_Relations.pdf" (PDF). External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ Lancaster, John (12 April 2005). "India, China Hoping to 'Reshape the World Order' Together". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 9 February 2011.

- ↑ "Why Indo-China ties will be more favourable than Sino-Pak". Theworldreporter.com. 7 July 2010. Archived from the original on 19 October 2010.

- ↑ India-China trade surpasses target, The Hindu, 27 January 2011.

- 1 2 Jeff M. Smith today's Wall Street Journal Asia (24 June 2009). "The China-India Border Brawl". WSJ. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ AK Antony admits China incursion Archived 30 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine., DNA, 28 September 2011.

- ↑ "China-Pakistan military links upset India". Financial Times. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ China warns India on South China Sea exploration projects Archived 24 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine., The Hindu, 15 September 2011.

- ↑ "US, China woo India for control over Asia-Pacific". The Times Of India. 7 June 2012.

- ↑ Goswami, Ranjit (4 May 2015). "PM Modi's China Visit: Cooperate for Development, Not Contain; and Not Both". SSRN. SSRN 2602123

.

. - ↑ "India-China bilateral trade set to hit $100 billion by 2015 - The Times of India". The Times of India. 21 June 2012. Archived from the original on 24 June 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ↑ IANS (28 November 2012). "China wants Free Trade agreement with India". Archived from the original on 13 November 2013.

- ↑ 2014 World Service Poll Archived 10 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. BBC

- ↑ "Chapter 4: How Asians View Each Other". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ Goswami, Ranjit (13 May 2015). "Make China India’s natural ally for development". Observer Research Foundation. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ↑ Goswami, Ranjit (11 May 2015). "Can Modi Make China India's Natural Ally for Development?". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- 1 2 "India Population (2017) - Worldometers". www.worldometers.info. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- 1 2 "China Population (2017) - Worldometers". www.worldometers.info. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ 2001 census Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. retrieved 20010630.

- ↑ Huang Xinchuan (1986), Hinduism and China, in Freedom, Progress, and Society (Editors: Balasubramanian et al.), ISBN 81-208-0262-4, pp. 125-138

- ↑ John Kieschnick and Meir Shahar (2013), India in the Chinese Imagination - Myth, Religion and Thought, ISBN 978-0812245608, University of Pennsylvania Press

- ↑ W.W. Rockhill (1914), Notes on the relations and trade of China with the Eastern Archipelago and the coasts of Indian Ocean during the 14th century", T'oung-Pao, 16:2

- ↑ T.N. Subramaniam (1978), A Tamil Colony in Medieval China, South Indian Studies, Society for Archaeological, Historical and Epigraphical Research, pp 5-9

- ↑ John Guy (2001), The Emporium of the World: Maritime Quanzhou 1000-1400 (Editor: Angela Schottenhammer), ISBN 978-9004117730, Brill Academic, pp. 294-308

- ↑ Ananth Krishnan. "Behind China’s Hindu temples, a forgotten history". The Hindu. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ China's Hindu temples: A forgotten history. 18 July 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2016 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "http://www.thehindu.com/multimedia/dynamic/01523/TH20_PAGE_1_ANANTH_1523758g.jpg". External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ "http://www.thehindu.com/multimedia/dynamic/01523/TH20_PAGE_ANANTH_S_1523759g.jpg". External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ "What to do in Quanzhou: China's forgotten historic port - CNN Travel". Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ Zürcher (1972), pp. 22–27.

- ↑ Hill (2009), p. 30, for the Chinese text from the Hou Hanshu, and p. 31 for a translation of it.

- ↑ Zürcher (1972), p. 23.

- ↑ Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism. 2000. p. 281

- 1 2 3 4 See Ōhashi (2008) in Astronomy: Indian Astronomy in China.

- 1 2 Joseph Needham, Volume 3, p. 109

- ↑ Whitfield, Susan. [2004] (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. British Library Staff. Serindia Publications, Inc. ISBN 1-932476-12-1

- ↑ Qian, Baocong (1964). "Zhongguo Shuxue Shi (The history of Chinese mathematics)". Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe.

- ↑ Wáng, Qīngxiáng (1999). Sangi o koeta otoko (The man who exceeded counting rods). Tokyo: Tōyō Shoten. ISBN 4-88595-226-3.

- ↑ Yabuuti, K.: Indian and Arabian Astronomy in China. In: The Silver Jubilee volume of the Zinbun-Kagaku-Kenkyusyo, Kyoto, pp. 585–603 (1954).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gupta, R. C. (7 July 2017). Ancient Indian Leaps into Mathematics. Birkhäuser, Boston, MA. pp. 33–44. doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-4695-0_2 – via link.springer.com.

- ↑ Mukhopadhyay, S. K. (ed.): The Sardulakarnavadana. Visvabharati, Santiniketan, pp. 46–53 and p. 104 (1954).

- ↑ 13 Vaidya, P. L. (ed.): Lalitavistara. Darbhanga, p. 103 (1958).

- ↑ "Science and Civilisation in China". Needham Research Institute.VOL-3,p.88.

- ↑ "Gupta, R. C.: Indian Astronomy in China During Ancient Times. Vishveshvaranand Indological Journal, XIX, 266–276, p. 270 (1981).".

- ↑ Wells, Marnix, and Naizhou Chang. Scholar Boxer: Chang Naizhou's Theory of Internal Martial Arts and the Evolution of Taijiquan. Berkeley, Calif: North Atlantic Books, 2004, p. 23

- ↑ Wells, Scholar Boxer, p. 200

- ↑ Johnson, Nathan J. Barefoot Zen: The Shaolin Roots of Kung Fu and Karate. York Beach, Me: S. Weiser, 2000, p. 48

- ↑ Subramaniam Phd., P., (general editors) Dr. Shu Hikosaka, Asst. Prof. Norinaga Shimizu, & Dr. G. John Samuel, (translator) Dr. M. Radhika (1994). Varma Cuttiram வர்ம சுத்திரம்: A Tamil Text on Martial Art from Palm-Leaf Manuscript. Madras: Institute of Asian Studies. pp. 90 & 91.

- ↑ Reid Phd., Howard, Michael Croucher (1991). The Way of the Warrior: The Paradox of the Martial Arts. Outlook Press. pp. 58–85. ISBN 0879514337. Unknown parameter

|Location=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - ↑ Cephas, Shawn (Winter 1994). "The Root of Warrior Priests in the Martial Arts". Kungfu Magazine.

- ↑ Wong, Kiew Kit. The Art of Shaolin Kung Fu: The Secrets of Kung Fu for Self-Defense Health and Enlightenment. Tuttle martial arts. Boston, Mass: Tuttle, 2002, p. 13

- ↑ Tang Hao 唐豪 (1968) [1930]. Shàolín Wǔdāng kǎo 少林武當考 (in Chinese). Hong Kong 香港: Qílín tushu.

- 1 2 Matsuda Ryuchi 松田隆智 (1986). Zhōngguó wǔshù shǐlüè 中國武術史略 (in Chinese). Taipei 臺北: Danqing tushu.

- ↑ Henning, Stanley (1994). "Ignorance, Legend and Taijiquan" (PDF). Journal of the Chenstyle Taijiquan Research Association of Hawaii. 2 (3): 1–7..

- 1 2 Henning, Stanley (1999b). "Martial Arts Myths of Shaolin Monastery, Part I: The Giant with the Flaming Staff". 5 (1). Unknown parameter

|Journal=ignored (|journal=suggested) (help) - ↑ Henry Davidson, A Short History of Chess, p. 6.

- ↑ Indian Embassy, Beijing. India-China Bilateral Relations - Historical Ties. Archived 21 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Tan Chung (1998). A Sino-Indian Perspective for India-China Understanding. Archived 6 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Old coins narrate Sino-Tamil story". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- 1 2 Smith, Vincent Arthur (1904), The Early History of India, The Clarendon press, pp. 336–358, ISBN 81-7156-618-9

- ↑ Srivastava, Balram (1973), Rajendra Chola, National Book Trust, India, p. 80,

The mission which Rajendra sent to China was essentially a trade mission,...

- ↑ D. Curtin, Philip (1984), Cross-Cultural Trade in World History, Cambridge University Press, p. 101, ISBN 0-521-26931-8

- ↑ Kamil V. Zvelebil (1987). "The Sound of the One Hand", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 107, No. 1, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Angela Schottenhammer (2008). The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-3-447-05809-4. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016.

- ↑ SEN, TANSEN. 2006. “The Yuan Khanate and India: Cross-cultural Diplomacy in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries”. Asia Major 19 (1/2). Academia Sinica: 317. Archived 27 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016..

- ↑ SEN, TANSEN. 2006. “The Yuan Khanate and India: Cross-cultural Diplomacy in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries”. Asia Major 19 (1/2). Academia Sinica: 317. Archived 27 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016..

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2016. p. 15.

- ↑ Ananth Krishnan. "Behind China’s Hindu temples, a forgotten history". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 June 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ China's Hindu temples: A forgotten history. 18 July 2013. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016 – via YouTube.

- ↑ China's Hindu temples: A forgotten history. 18 July 2013. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "http://www.thehindu.com/multimedia/dynamic/01523/TH20_PAGE_1_ANANTH_1523758g.jpg". Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ "http://www.thehindu.com/multimedia/dynamic/01523/TH20_PAGE_ANANTH_S_1523759g.jpg". Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ "What to do in Quanzhou: China's forgotten historic port - CNN Travel". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ The Sino-Indian Border Disputes, by Alfred P. Rubin, The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Jan., 1960), pp. 96-125.

- ↑ "Don't believe in Hindi-Chini bhai-bhai, Nehru told envoy". Indian Express. Archived from the original on 5 March 2011.

- ↑ "‘China, India and the fruits of Nehru’s folly’". dna. 6 June 2007. Archived from the original on 19 March 2009. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ "Nehru's legacy to India". Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ <The Foreign Policy of Sirimavo Bandaranaike - THE COLOMBO POWERS AND THE SINO-INDIAN WAR OF 1962>

- ↑ "http://www.amar-jawan.org/querypage.asp?forceid=1". Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ "http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/LAND-FORCES/Army/History/1960s/Chola.html". Archived from the original on 25 May 2007. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ "Rapprochement Across the Himalayas: Emerging India-China Relations Post Cold""Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015. p. 40

- ↑ Ananth Krishnan. "Huang Hua, diplomat who helped thaw ties with India, passes away". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ "Military common sense". Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 "http://www.indiatodaygroup.com/itoday/18051998/cover.html". Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ India's Land of the Rising Sun Archived 31 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Deccan Herald

- ↑ "Obituary: Warrior as Scholar: Gen (retd) K Sundarji (1928-1999)". Archived from the original on 24 September 2009. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ "http://www.deccanherald.com/deccanherald/sep03/edst.asp". Archived from the original on 23 February 2005. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ "Why is China alienating half a billion young Indians?". scmp.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "India-China trade link to reopen" Archived 21 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine., BBC News, 19-06-2006. Retrieved on 31-01-2007.

- ↑ "India and China row over border" Archived 15 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine., BBC News, 14-11-2006. Retrieved on 31-01-2007.

- ↑ "China denies visa to IAS officer". CNN-IBN. 25 May 2007. Archived from the original on 21 August 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS - South Asia - Chinese 'border gesture' to India". Archived from the original on 18 July 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ "A thaw? China lets Arunachalee visit". The Times of India. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ David Miliband, Written Ministerial Statement on Tibet (29/10/2008) Archived 2 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine., Foreign Office website, Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ↑ Richard Spencer, UK recognises China's direct rule over Tibet Archived 3 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine., The Daily Telegraph, 5 November 2008

- ↑ Shai Oster, U.K. Policy Angers Tibet Ahead of Beijing Talks, The Wall Street Journal, 1 November 2008

- ↑ Staff, Britain's suzerain remedy Archived 10 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine., The Economist, 6 November 2008

- ↑ Robert Barnett, Did Britain Just Sell Tibet? Archived 5 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine., The New York Times, 24 November 2008

- ↑ "Project Records | Asian Development Bank". Adb.org. 11 September 2008. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ↑ "China objected to ADB loan to India". The New Indian Express. 9 July 2009. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ↑ "China objected to ADB loan to India for Arunachal project: Krishna (Lead) - Thaindian News". Thaindian.com. 9 July 2009. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ↑ "Chinese premier urges closer cultural, youth links with India - People's Daily Online". English.peopledaily.com.cn. 17 December 2010. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ↑ "Chinese PM Wen Jiabao begins bumper Indian trade trip". BBC News. 15 December 2010. Archived from the original on 26 January 2011.

- ↑ "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India - Main News". Tribuneindia.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ↑ "Indian PM Manmohan Singh heads to China for talks". BBC News. 11 April 2011. Archived from the original on 12 April 2011.

- ↑ "Nri". The Times Of India. 13 April 2011. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "India, China to restore defence co-operation : Neighbours, News - India Today". Indiatoday.intoday.in. 13 April 2011. Archived from the original on 1 August 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ↑ "2011: India, China solve stapled visa issue; put off border talks". The Times Of India. 23 December 2011. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017.

- ↑ "India to reach US$100 billion dollar trade with China by 2015". Economic Times. 9 February 2012.

- ↑ "India Gripes Over Border, Trade Woes on Li's First Foreign Trip". Reuters. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ↑ "China wants to deepen strategic cooperation with India: Hu Jintao". The Times Of India. 30 March 2012. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017.

- ↑ Nelson, Dean. "China warns India of arrogance over missile launch." Archived 20 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine. The Telegraph. 20 April 2012.

- ↑ Reuters Editorial (6 May 2013). "India says China agrees retreat to de facto border in faceoff deal". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ Defence News. "India Destroyed Bunkers in Chumar to Resolve Ladakh Row" Archived 24 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine.. Defence News. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "Chinese premier visits India". Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ "Joint Statement on the State Visit of Chinese Premier Li Keqiang to India". Ministry of External Affairs (India). 20 May 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ↑ Aakriti Bachhawat; The Diplomat. "China’s Arunachal Pradesh Fixation". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ "China reiterates claim on Arunachal Pradesh through mouthpiece - The Times of India". Archived from the original on 3 September 2014.

- ↑ "Chinese troops said to be 2 km inside LAC, build-up on the rise". The Indian Express. 23 September 2014. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ Krishnan, Ananth (31 October 2014). "Delhi, Kabul warn China: Pak maybe your ally but it exports terror". intoday.in. Living Media India Limited. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ Patrick Frater (4 November 2015). "AFM: Golden Network Kicks Off With Jackie Chan Movie Pair". variety.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ↑ "India to boycott China summit amid Kashmir concerns". channelnewsasia.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Liu Lin, India-China Doklam Standoff: A Chinese Perspective Archived 29 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine., The Diplomat, 27 July 2017

- 1 2 3 4 Staff, The Wire. "India-China Face-Off: Watch Manoj Joshi and M.K. Venu Discuss". thewire.in. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "印度边防部队在中印边界锡金段越界 进入中国领土的事实和中国的立场" (pdf) (in Chinese). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2017.

- 1 2 "China accuses India of breaching 1890 border pact that 'must be respected'". 3 July 2017. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ Doklam has always been under China's effective jurisdiction without dispute: FM Archived 29 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine., Xinhua, 24 July 2017

- ↑ "No dispute with Bhutan in Doklam: China". The Economic Times. 17 April 2017. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017.

- ↑ "China urges India to withdraw border guards crossing the boundary". China Daily. 27 June 2017. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017.

- ↑ "What's behind the India-China border stand-off?". BBC News. 5 July 2017. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ↑ "India's reasons for trespassing slammed". China Daily. 7 July 2017. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017.

- ↑ "'Ball is in India's court': China says Doklam situation 'grave', rules out compromise - Times of India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ↑ "Bhutan issues demarche to China over its army’s road construction". 28 June 2017. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ Indian elites stand to gain from advocating ‘China threat’ theory Archived 31 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "If China unilaterally changes status-quo in Doklam, it’s a challenge to our security: Sushma Swaraj". indianexpress.com. 20 July 2017. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Sikkim standoff: Chinese media says India will suffer ‘greater losses’ than 1962 if it ‘incites’ border tensions". The Indian Express. 5 July 2017. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ↑ PTI (5 July 2017). "Withdraw with dignity or be kicked out, Chinese media threatens India". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ↑ "China may have quietly moved tonnes of war gear into northern Tibet, claims report". The Economic Times. 2017-07-19. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ↑ "US 'concerned' about India-China border standoff, says 'both sides should work together' for peace - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ↑ ANI (10 July 2017). "Doklam stand-off: China wants India to retreat for meaningful dialogue". Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017 – via Business Standard.

- ↑ CGTN (18 July 2017). "China urges India to withdraw troops from Chinese territory". Retrieved 27 July 2017 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Rise of the India (20 July 2017). "China said India's withdrawal a prerequisite for meaningful dialogue". Retrieved 27 July 2017 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Chaudhury, Dipanjan Roy (21 July 2017). "For dialogue, both India and China must withdraw troops, says Sushma Swaraj". Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017 – via The Economic Times.

- ↑ China issues position document on Indian border troop trespass

- ↑ Blanchard, Ben (August 4, 2017). "China says India building up troops amid border stand-off". Reuters. Yahoo.

- ↑ 解放军罕见强硬表态 印度提出一条件 答应就班师回家!

- ↑ "Top China Imports". Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- 1 2 "Top China Exports". Archived from the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ "Top India Imports". Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

Further reading

- Lokesh Chandra. 2016. India and China. New Delhi : International Academy of Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan, 2016.

- Yutang, Lin. 1942. The wisdom of China and India. New York: Random House.

- Chaudhuri, S. K. (2011). Sanskrit in China and Japan. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan.

- De, B. W. T. (2011). The Buddhist tradition in India, China & Japan. New York: Vintage Books.

- Bagchi, Prabodh Chandra, Bangwei Wang, and Tansen Sen. 2012. India and China: interactions through Buddhism and diplomacy : a collection of essays by Professor Prabodh Chandra Bagchi. Singapore: ISEAS Pub.

- Chellaney, Brahma, "Rising Powers, Rising Tensions: The Troubled China-India Relationship," SAIS Review (2012) 32#2 pp. 99–108 in Project MUSE

- Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2011). "Past, present and future commercial Sino-Indian links via Sikkim," in: China's Ancient Tea Horse Road. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B005DQV7Q2

- Frankel, Francine R., and Harry Harding. The India-China Relationship: What the United States Needs to Know. Columbia University Press: 2004. ISBN 0-231-13237-9.

- Garver, John W. Protracted Contest: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Twentieth Century. University of Washington Press: 2002. ISBN 0-295-98074-5.

- Harris, Tina (2013). Geographical Diversions: Tibetan Trade, Global Transactions. University of Georgia Press, United States. ISBN 0820345733. pp. 208.

- Hellström, Jerker and Korkmaz, Kaan "Managing Mutual Mistrust: Understanding Chinese Perspectives on Sino-Indian Relations", Swedish Defence Research Agency (September 2011)

- Lintner, Bertil. Great game east: India, China, and the struggle for Asia's most volatile frontier (Yale University Press, 2015)

- Lu, Chih H.. The Sino-Indian Border Dispute: A Legal Study. Greenwood Press: 1986. ISBN 0-313-25024-3.

- China’s Response to a Rising India, Q&A with M. Taylor Fravel (October 2011)

- Strategic Asia 2011-12: Asia Responds to Its Rising Powers - China and India, edited by Ashley J. Tellis, Travis Tanner, and Jessica Keough (National Bureau of Asian Research, 2011)

- India’s Response to a Rising China: Economic and Strategic Challenges and Opportunities, Q&A with Harsh V. Pant (August 2011)

- Davies, Henry Rudolph. 1970. Yün-nan, the link between India and the Yangtze. Taipei: Ch'eng wen.

- Sen, Tansen. Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations, 600-1400. University of Hawaii Press: 2003. ISBN 0-8248-2593-4.

- Sidhu, Waheguru Pal Singh, and Jing Dong Yuan. China and India: Cooperation or Conflict? Lynne Rienner Publishers: 2003. ISBN 1-58826-169-7.

- Varadarajan, S. India, China and the Asian Axis of Oil, January 2006

- The India-China Relationship:What we need to know?, January 2006

- Dalal, JS: The Sino-Indian Border Dispute: India's Current Options. Master's Thesis, June 1993.

- Deepak, BR & Tripathi, D P "India China Relations - Future Perspectives", Vij Books, July 2012

- http://www.academia.edu/7767087/Maritime_Interactions_between_China_and_India

- http://www.academia.edu/7767082/Maritime_Southeast_Asia_Between_South_Asia_and_China_to_the_Sixteenth_Century

- https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/23052/1/%2313_Sen.pdf

.svg.png)