Chikka Devaraja

| Chikka Devaraja | |

|---|---|

| Wodeyar of Mysore | |

| |

| Reign | 1673–1704 |

| Predecessor | Dodda Devaraja |

| Successor | Kanthirava Narasaraja II |

| Born | 22 September 1645 |

| Died | 16 November 1704 |

| House | Wodeyar |

| Mysore Kings (1399–present) | |

| Feudatory Monarchy (As vassals of Vijayanagara Empire) (1399–1553) | |

| Yaduraya Wodeyar | (1399–1423) |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar I | (1423–1459) |

| Timmaraja Wodeyar I | (1459–1478) |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar II | (1478–1513) |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar III | (1513–1553) |

| Absolute Monarchy (Independent Wodeyar Kings) (1553–1761) | |

| Timmaraja Wodeyar II | (1553–1572) |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar IV | (1572–1576) |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar V | (1576–1578) |

| Raja Wodeyar I | (1578–1617) |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar VI | (1617–1637) |

| Raja Wodeyar II | (1637–1638) |

| Narasaraja Wodeyar I | (1638–1659) |

| Dodda Devaraja Wodeyar | (1659–1673) |

| Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar | (1673–1704) |

| Narasaraja Wodeyar II | (1704–1714) |

| Krishnaraja Wodeyar I | (1714–1732) |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar VII | (1732–1734) |

| Krishnaraja Wodeyar II | (1734–1761) |

| Puppet Monarchy (Under Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan) (1761–1799) | |

| Krishnaraja Wodeyar II | (1761–1766) |

| Nanjaraja Wodeyar | (1766–1770) |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar VIII | (1770–1776) |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar IX | (1776–1796) |

| Puppet Monarchy (Under British Rule) (1799–1831) | |

| Krishnaraja Wodeyar III | (1799–1831) |

| Titular Monarchy (Monarchy abolished) (1831–1881) | |

| Krishnaraja Wodeyar III | (1831–1868) |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar X | (1868–1881) |

| Absolute Monarchy Monarchy restored (As allies of the British Crown) (1881–1947) | |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar X | (1881–1894) |

| Krishnaraja Wodeyar IV | (1894–1940) |

| Jayachamaraja Wodeyar | (1940–1947) |

| Constitutional Monarchy (In Dominion of India) (1947–1950) | |

| Jayachamaraja Wodeyar | (1947–1950) |

| Titular Monarchy (Monarchy abolished) (1950–present) | |

| Jayachamaraja Wodeyar | (1950–1974) |

| Srikanta Wodeyar | (1974–2013) |

| Yaduveera Chamaraja Wadiyar | (2015–present) |

Chikka Deva Raja (also Chikka Deva Raja Wodeyar) was the wodeyar ruler of Mysore (then a principality or petty kingdom in southern India) from 1673 to 1704.[1] During this time, Mysore saw significant expansion and also recognition by the Mughal empire as a tributary state. During his rule centralized military power increased to an unprecedented degree for the region.[2]

Early years

Chikka Devaraja was born on 22 September 1645, the eldest son of Rani Amrit Ammani and Dodda Deva Raja, who had been a Governor of Mysore town. He succeeded his uncle, Dodda Deva Raja, upon the latter's death on 11 February 1673, as the new wodeyar. He was installed on the gaddi at Mysore on 28 February 1673. He continued his predecessor's expansion by conquering Maddagiri, and thereby making Mysore contiguous to the Carnatic-Bijapur-Balaghat province administered by Venkoji, the Raja of Tanjore, and Shivaji's half-brother.

Taxation and the Jangama massacre

In the first decade of his rule, Chikka Devaraja introduced various petty taxes that were mandatory for the peasants, but that his soldiers were exempted from.[3] The unusually high taxes and the intrusive nature of his regime, created wide protests in the ryots which had the support of the Jangama priests in the Virasaiva monasteries.[4] According to (Nagaraj 2003), a slogan of the protests was:

"Basavanna the Bull tills the forest land; Devendra [Indra] gives the rains;

Why should we, the ones who grow crops through hard labor, pay taxes to the king?"[5]

As per the unverified sources, the king, resolving upon a "treacherous massacre,"[6] used the stratagem of inviting over 400 priests to a grand feast at the famous Shaivite center of Nanjanagudu, and upon its conclusion having them first receive gifts and then exit one at a time through a narrow lane, whereupon his royal wrestlers strangled each exiting priest.[5] This "sanguinary measure" had the effect of stopping all protests to the new taxes.[6] Around this time, 1687, Chikka Devaraja also made an agreement with Venkoji to purchase Bengaluru (which later became Bangalore city and Bangalore Rural district) for Rs. 3 lakhs.[6]

Relations with the Mughal empire

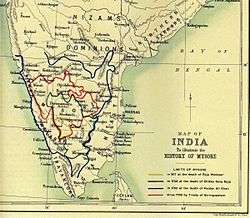

However, soon thereafter, the Mughals under Aurangzeb invaded the region and, having conquered the Maratha-Bijapur province of Carnatic-Bijapur-Balaghat (of which Bangalore was a part), made it a part of the Mughal province of Sira. The payment for Bangalore was consequently made to Qasim Khan, the Mughal Faujdar Diwan of Sira and through him Chikka Devaraja "assiduously cultivated an alliance" with Aurangzeb.[6] He also soon turned his attention to the regions to his south which were less the objects of Moghul interest.[6] The regions around Baramahal and Salem below the Eastern Ghats were now annexed to Mysore, and in 1694 were extended by the addition of regions to the west up to the Baba Budan mountains.[6] Two years later Chikka Devaraja attacked the lands of the Naik of Madura and laid a siege of Trichinopoly.[6] Soon, however, Qasim Khan, his Mughal liaison, died. With the intention of either renewing his Mughal connections or seeking Mughal recognition of his southern conquests, Chikka Devaraja sent an embassy to Aurangzeb, at Ahmadnagar.[6] In response, in 1700, the Mughal emperor sent the Mysore Raja a signet ring Seal "bearing the title Jug Deo Raj" (literally, "lord and king of the world"), and permission to sit on an ivory throne, and also a Sword from Aurangzeb's personal Regalia, a Firangi (sword),( see Swords of India ), with Gold Etching on the Hilt, to be used as a Sword of State by the Mysore Raja, while seated on the Ivory Throne. "[6] Chikka Devaraja at this time also reorganized his administration into eighteen departments, in "imitation of what the envoys had seen at the Mughal court."[6] When the Raja died on November 16, 1704, his dominions extended from Midagesi in the north to Palni and Anaimalai in the south, and from Kodagu and Balam in the west to Baramahals in the east.[6]

Legacy

According to Subrahmanyam 1989, the state that Chikka Devaraja left for his son was "at one and the same time a strong and a weak state."[7] Although it had uniformly expanded in size from the mid-seventeenth century to the early eighteenth, it had done so as a result of alliances that tended to hinder the very stability of the expansions.[8] Some of the southeastern conquests described above (such as of Salem), although involving regions that were not of direct interest to the Mughals, were nonetheless the result of alliances with Mughal Faujdar Diwan of Sira and with Venkoji, the Maratha ruler of Tanjore.[8] For example, the siege of Trichnopoly had to be abandoned because the alliance had begun to rupture.[8] Similarly, in addition to receiving a signet ring and a Sword described above, a consequence of the embassy sent to Aurangzeb in the Deccan in 1700 was formal subordination to Mughal authority and a requirement to pay annual tribute.[8] There is evidence, too, that the administrative reforms mentioned above might have been a direct result of Mughal influence.[8]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Bandyopadhyay 2004, p. 33

- ↑ Bandyopadhyay 2004, p. 33, Stein 1985b, pp. 400–401

- ↑ Stein 1985b, pp. 400–401

- ↑ Stein 1985b, pp. 400–401, Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, pp. 20–21

- 1 2 Nagaraj 2003, pp. 378–379

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, pp. 20–21

- ↑ Subrahmanyam 1989, p. 212

- 1 2 3 4 5 Subrahmanyam 1989, p. 213

References

- Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (2004), From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India, New Delhi and London: Orient Longmans. Pp. xx, 548., ISBN 81-250-2596-0

- Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series (1908), Mysore and Coorg, Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing. Pp. xvii, 365, 1 map.

- Nagaraj, D. R. (2003), "Critical Tensions in the History of Kannada Literary Culture", in Pollock, Sheldon, Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia, Berkeley and London: University of California Press. Pp. 1066, pp. 323–383

- Stein, Burton (1985b), "State Formation and Economy Reconsidered: Part One", Modern Asian Studies, 19 (3, Special Issue: Papers Presented at the Conference on Indian Economic and Social History, Cambridge University, April 1984): 387–413, JSTOR 312446, doi:10.1017/S0026749X00007678

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (1989), "Warfare and state finance in Wodeyar Mysore, 1724–25: A missionary perspective", Indian Economic Social History Review, 26 (2): 203–233, doi:10.1177/001946468902600203