Chigi vase

The Chigi vase is a Protocorinthian olpe, or pitcher, that is the name vase of the Chigi Painter.[1] It was found in an Etruscan tomb at Monte Aguzzo, near Veio, on Prince Mario Chigi’s estate in 1881.[2] The vase has been variously assigned to the middle and late protocorinthian periods and given a date of ca. 650-640 BC;[3] it is now in the National Etruscan Museum, Villa Giulia, Rome (inv. No.22679). Some three-quarters of the vase is preserved. It was found amidst a large number of potsherds of mixed provenance, including one bucchero vessel inscribed with five lines in two early Etruscan alphabets announcing the ownership of Atianai, perhaps also the original owner of the Chigi vase.[4]

Mythological scenes

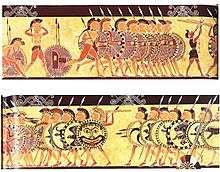

The Chigi vase itself is a polychromatic work decorated in four friezes of mythological and genre scenes and four bands of ornamentation; amongst these tableaux is the earliest representation of the hoplite phalanx formation – the sole pictorial evidence of its use in the mid- to late-7th century,[5] and terminus post quem of the "hoplite reform" that altered military tactics.

The lowest frieze is a hunting scene in which three naked short-haired hunters and a pack of dogs endeavour to catch hares and one vixen; a kneeling hunter carries a lagobolon (a throwing cudgel used in coursing hares) as he signals to his fellows to stay behind a bush. It is not clear from the surviving fragments if a trap is being used,[6] as was common in depictions of such expeditions. The next frieze immediate above suggests a collocation of four or five unrelated events. First a parade of long-haired horsemen, each of whom is leading a riderless horse. Possibly these are squires or hippobates for some absent cavalrymen or hippobateis;[7] the latter, it has been conjectured, may be the hoplites seen elsewhere on the vase.[8] The riders are confronted with a two-bodied sphinx with a floral crown and an archaic smile. It is not clear if the creature is participating in any of the action in this frieze.[9] Behind the sphinx is a lion-hunting scene in which four youths wearing cuirasses (save for one who is nude, but belted) spear a lion which has a fifth figure in its jaws. Whether there were indigenous lions in the Peloponnese at this time is a matter for speculation.[10] moreover the shock-haired mane of the lion betrays a neo-Assyrian influence, perhaps the first such in Corinthian art and replacing the previously dominant Hittite forms.[11] Finally in this section, and just below the handle, is a Judgement of Paris scene. Above is another hunting scene, albeit of animals only: dogs chasing stags, goats and hares.

In the highest and largest frieze is the scene that has attracted the most scholarly attention – a battle involving hoplite warfare. However this characterization is not without its problems. For one thing, the hoplites shown here meeting at the moment of othismos (or "push") do not carry short swords, but instead like their Homeric forebears have two spears; one for thrusting and one for throwing. Further, Tyrtaeus (11.11-14 West) does not mention a supporting second rank as it may be represented; it is far from self-evident this is a second rank depicted on the vase or that it supports the first. To render the phalanx tactics unambiguously the painter would have had to have given a bird's-eye view of the action, a perspective unknown in Greek vase painting. Consequently it is not clear if the hoplite formation shown here is the developed form as it was practiced from the 6th century onwards. Lastly flautists and cadenced marching are not attested in literature from the Archaic Period, so the flute-player drawn here cannot have served in reality to keep the troops in step:[12] what function he had, if any, is open to speculation. However, Thucydides does state that a Spartan phalanx in the Battle of Mantinea was accompanied by flutists in order to keep step as they approached the opposing army, which may suggest that they were used in the same way at the time when the vase was made.[13]

Judgement of Paris

The Judgement of Paris on the Chigi vase is the earliest extant depiction of the myth, evidence perhaps of knowledge of the lost epic Cypria from the 650s. The figure of Paris is labelled Alexandros in the Homeric manner, though the writer might not be the same as the painter since the inscriptions are not typically Corinthian.[14] This scene, obscured under the handle and “painted somehow as an afterthought” according to John Boardman.[15] invites the question whether the events on this vase (and vases generally) are random juxtapositions of images or present a narrative or overarching theme. In line with recent scholarship of the Paris structuralist school[16] Jeffrey Hurwit suggests that reading upwards along the vertical axis we can discern the development of the ideal Corinthian man from boyhood through agones and paideia to full warrior-citizen, with the sphinx marking the liminal stages in his maturation.[17]

References

- ↑ Amyx 1988, 31-33, and Benson, Earlier Corinthian Workshops, 1989, 56-58, call the artist the Chigi Painter. However Dunbabin and Robertson, "Some Protocorinthian Vase Painters", Annual of the British School at Athens, 48, 1953, 179-180 favour the appellation "Macmillan Painter".

- ↑ Ghirardini 1882, p. 292.

- ↑ Hurwitt, p. 3, note 12, lists the competing views on the date.

- ↑ Hurwitt, 2002, p. 6.

- ↑ ”not just the first but the best representations”, Murray, Early Greece, 1993, p. 130. The Chigi vase is predated by the Macmillan aryballos depicting hoplite single combat (BM GR 1889.4-18.1).

- ↑ Schnapp, 1989, figs. 99-100, some arching lines in the zone above might indicate a trap.

- ↑ Suggests Hurwitt, 2002, p. 10.

- ↑ Greenhalgh, 1973, pp. 85-86.

- ↑ Hurwitt points out that shinxes are not menacing monsters in the Corinthian mythography. Hurwitt, 2002, pp. 10.

- ↑ Herodotus 7.125-6 notwithstanding, imported lions and products from lions would have been known; however lions disappear from Corinthian vase painting by 550: see H. Payne, Necrocorinthia: a study of Corinthian art in the archaic period, 1931, p. 67-69.

- ↑ Hurwitt, 2002, pp. 12.

- ↑ Hanson, Hoplites, n.49, p. 160.

- ↑ Thuc. 5.70

- ↑ Either Aiginetan or Syracusan, see Hurwit, 2002, note.21

- ↑ J. Boardman, ed. Oxford History of Classical Art, 1993, pp. 31-32.

- ↑ The structuralist approach of Victor Bérard, François Lissarrague etc.

- ↑ Hurwit, 2002, p. 18.

Sources

- D. A. Amyx, Corinthian Vase Painting of the Archaic Period, 1988.

- Jeffrey M. Hurwit, "Reading the Chigi Vase", Hesperia, Vol. 71, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 2002), pp. 1–22.

- John Salmon, "Political Hoplites?", The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 97, (1977), pp. 84–101.