Chief Joseph

| Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it (Chief Joseph) | |

|---|---|

1877 | |

| Native name | Hinmatóowyalahtq'it |

| Born |

March 3, 1840 Wallowa Valley, Oregon, US |

| Died |

September 18, 1904 (aged 64) Colville Indian Reservation, Washington, US |

| Cause of death | "A broken heart"[1] |

| Resting place |

Chief Joseph Cemetery Nespelem, Washington 48°10′6.72″N 118°58′37.69″W / 48.1685333°N 118.9771361°WCoordinates: 48°10′6.72″N 118°58′37.69″W / 48.1685333°N 118.9771361°W |

| Other names |

|

| Known for | Nez Perce leader |

| Predecessor | Joseph the Elder (father) |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | Jean-Louise (daughter) |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

| |

Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt, Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it in Americanist orthography, popularly known as Chief Joseph or Young Joseph (March 3, 1840 – September 18, 1904), succeeded his father Tuekakas (Chief Joseph the Elder) as the leader of the Wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa) band of Nez Perce, a Native American tribe indigenous to the Wallowa Valley in northeastern Oregon, in the interior Pacific Northwest region of the United States.

He led his band during the most tumultuous period in their contemporary history when they were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands in the Wallowa Valley by the United States federal government and forced to move northeast, onto the significantly reduced reservation in Lapwai, Idaho Territory. A series of events that culminated in episodes of violence led those Nez Perce who resisted removal, including Joseph's band and an allied band of the Palouse tribe, to take flight to attempt to reach political asylum, ultimately with the Lakota led by Sitting Bull, who had sought refuge in Canada.

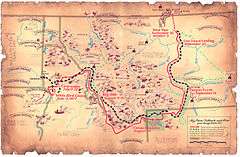

They were pursued eastward by the U.S. Army in a campaign led by General Oliver O. Howard. This 1,170-mile (1,900 km) fighting retreat by the Nez Perce in 1877 became known as the Nez Perce War. The skill with which the Nez Perce fought and the manner in which they conducted themselves in the face of incredible adversity led to widespread admiration among their military adversaries and the American public.

Coverage of the war in United States newspapers led to widespread recognition of Joseph and the Nez Perce. For his principled resistance to the removal, he became renowned as a humanitarian and peacemaker. However, modern scholars, like Robert McCoy and Thomas Guthrie, argue that this coverage, as well as Joseph's speeches and writings, distorted the true nature of Joseph's thoughts and gave rise to a "mythical" Chief Joseph as a "red Napoleon" that served the interests of the Anglo-American narrative of manifest destiny.

Background

Chief Joseph was born Hinmuuttu-yalatlat (alternatively Hinmaton-Yalaktit or Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt (Nez Perce: "Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain"), or Hinmatóoyalahtq'it ("Thunder traveling to higher areas")[2] in the Wallowa Valley of north eastern Oregon. He was known as Young Joseph during his youth because his father, Tuekakas,[3] was baptized with the same Christian name and later become known as "Old Joseph" or "Joseph the Elder".[4]

While initially hospitable to the region's newcomers, Joseph the Elder grew wary when settlers wanted more Indian lands. Tensions grew as the settlers appropriated traditional Indian lands for farming and grazing livestock.

Isaac Stevens, governor of the Washington Territory, organized a council to designate separate areas for natives and settlers in 1855. Joseph the Elder and the other Nez Perce chiefs signed the Treaty of Walla Walla[5] with the United States establishing a Nez Perce reservation encompassing 7.7 million acres (31,000 km²) in present-day Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. The 1855 reservation maintained much of the traditional Nez Perce lands, including Joseph's Wallowa Valley.[6] It is recorded that Chief Joseph's father requested that Young Joseph protect their 7.7-million-acre homeland, and guard his father's burial place.[7]

An influx of new settlers, attracted by a gold rush, led the government to call a second council in 1863. Government commissioners asked the Nez Perce to accept a new, much smaller reservation of 760,000 acres (3,100 km2) situated around the village of Lapwai in Idaho, and excluding the Wallowa Valley.[8][9] In exchange, they were promised financial rewards, schools, and a hospital for the reservation. Chief Lawyer and one of his allied chiefs signed the treaty on behalf of the Nez Perce Nation, but Joseph the Elder and several other chiefs were opposed to selling their lands and did not sign.[10][11][12][13]

Their refusal to sign caused a rift between the "non-treaty" and "treaty" bands of Nez Perce. The "treaty" Nez Perce moved within the new reservation's boundaries, while the "non-treaty" Nez Perce remained on their lands. Joseph the Elder demarcated Wallowa land with a series of poles, proclaiming, "Inside this boundary all our people were born. It circles the graves of our fathers, and we will never give up these graves to any man."

Leadership of the Nez Perce

Joseph the Younger succeeded his father as leader of the Wallowa band in 1871. Before his death, the latter counseled his son:

My son, my body is returning to my mother earth, and my spirit is going very soon to see the Great Spirit Chief. When I am gone, think of your country. You are the chief of these people. They look to you to guide them. Always remember that your father never sold his country. You must stop your ears whenever you are asked to sign a treaty selling your home. A few years more and white men will be all around you. They have their eyes on this land. My son, never forget my dying words. This country holds your father's body. Never sell the bones of your father and your mother.[14]

Joseph commented: "I clasped my father's hand and promised to do as he asked. A man who would not defend his father's grave is worse than a wild beast."

The non-treaty Nez Perce suffered many injustices at the hands of settlers and prospectors, but out of fear of reprisal from the militarily superior Americans, Joseph never allowed any violence against them, instead making many concessions to them in hopes of securing peace.

In 1873, Joseph negotiated with the federal government to ensure his people could stay on their land in the Wallowa Valley. But in 1877, the government reversed its policy, and Army General Oliver Howard threatened to attack if the Wallowa band did not relocate to the Idaho Reservation with the other Nez Perce. Joseph reluctantly agreed. Before the outbreak of hostilities, General Howard held a council at Fort Lapwai to try to convince Joseph and his people to relocate. Joseph finished his address to the general, which focused on human equality, by expressing his "[disbelief that] the Great Spirit Chief gave one kind of men the right to tell another kind of men what they must do." Howard reacted angrily, interpreting the statement as a challenge to his authority. When Toohoolhoolzote protested, he was jailed for five days.

The day following the council, Joseph, White Bird, and Looking Glass all accompanied Howard to look at different areas. Howard offered them a plot of land that was inhabited by whites and Native Americans, promising to clear out the current residents. Joseph and his chieftains refused, adhering to their tribal tradition of not taking what did not belong to them.

Unable to find any suitable uninhabited land on the reservation, Howard informed Joseph that his people had 30 days to collect their livestock and move to the reservation. Joseph pleaded for more time, but Howard told him he would consider their presence in the Wallowa Valley beyond the 30-day mark an act of war.

Returning home, Joseph called a council among his people. At the council, he spoke on behalf of peace, preferring to abandon his father's grave over war. Toohoolhoolzote, insulted by his incarceration, advocated war. The Wallowa band began making preparations for the long journey, meeting first with other bands at Rocky Canyon. At this council too, many leaders urged war, while Joseph argued in favor of peace. While the council was underway, a young man whose father had been killed rode up and announced that he and several other young men had already killed four white settlers. Still hoping to avoid further bloodshed, Joseph and other non-treaty Nez Perce leaders began moving people away from Idaho.

Nez Perce War

The Nez Perce War was the name given to the U.S. Army's pursuit of about 750 Nez Perce and a small allied band of the Palouse tribe who had fled toward freedom. Initially they had hoped to take refuge with the Crow nation in the Montana Territory, but when the Crow refused to grant them aid, the Nez Perce went north in an attempt to reach asylum with the Lakota band led by Sitting Bull, who had fled to Canada in 1876. In “Hear Me, My Chiefs!: Nez Perce Legend and History”, Lucullus V. McWhorter argues that the Nez Perce were a peaceful people that were forced into war by the United States when their land was stolen from them. McWhorter interviewed and befriended Nez Perce warriors such as Yellow Wolf who stated, “Our hearts have always been in the valley of the Wallowa”.[15]

Robert Forczyk states in his book “Nez Perce 1877: The Last Fight” that the tipping point of the war was that “Joseph responded that his clan’s traditions would not allow him to cede the Wallowa Valley”.[16] The Nez Perce band led by Chief Joseph never signed the treaty moving them to the Idaho reservation. General Howard was dispatched to deal with Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce, he tended to believe the Nez Perce were right about the treaty, “the new treaty finally agreed upon excluded the Wallowa, and vast regions besides".[17]

For over three months, the Nez Perce outmaneuvered and battled their pursuers, traveling 1,170 miles (1,880 km) across Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana. One of those battles was led by Captain Perry and two Cavalry companies of the U.S. Army, they engaged Chief Joseph and his people at White Bird Canyon, the Nez Perce repelled the attack, killing 34 soldiers, while leaving only 3 Nez Perce injured. The Nez Perce would continue to repel the Army’s advances, the Nez Perce reached the Clearwater River where they united with another Nez Perce Chief, Looking Glass and his group, now totaling 740 with only 200 of those warriors.[16] The final battle occurred approximately 40 miles from Canada, the Nez Perce camped on Snake Creek near Bear Paw Mountain. Colonel Nelson Miles along with Cheyenne scouts intercepted the Nez Perce, after his initial attacks were repelled, Miles captured Chief Joseph after violating a truce, however he would be later forced to exchange Chief Joseph for one of his captured officers.[16]

General Howard, leading the opposing cavalry, was impressed with the skill with which the Nez Perce fought, using advance and rear guards, skirmish lines, and field fortifications. Finally, after a devastating five-day battle during freezing weather conditions with no food or blankets, with the major war leaders dead, Joseph formally surrendered to General Nelson Appleton Miles on October 5, 1877 in the Bear Paw Mountains of the Montana Territory, less than 40 miles (60 km) south of Canada in a place close to the present-day Chinook, in Blaine County.

The battle is remembered in popular history by the words attributed to Joseph at the formal surrender:

Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have it in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed; Looking Glass is dead, Too-hul-hul-sote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led on the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets; the little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, to see how many I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.[18]

The popular legend deflated, however, when the original pencil draft of the report was revealed to show the handwriting of the later poet and lawyer Lieutenant Charles Erskine Scott Wood, who claimed to have taken down the great chief's words on the spot. In the margin it read, "Here insert Joseph's reply to the demand for surrender"[19][20] Although Joseph was not technically a war chief and probably did not command the retreat, many of the chiefs who did had died. His speech brought attention – and therefore credit – his way. He earned the praise of General William Tecumseh Sherman and became known in the press as "The Red Napoleon". However, as Francis Haines argues in “Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce Warriors”, the battlefield successes of the Nez Perce during the Nez Perce War of 1877 were due to the individual successes of the Nez Perce men and not that of the fabled military genius of Chief Joseph. Haines supports his argument by citing L.V. McWhorter who concluded “that Chief Joseph was not a military man at all, that on the battlefield he was without either skill or experience".[21] Furthermore, Merle Wells argues in “The Nez Perce and Their War”, that the interpretation of the Nez Perce War of 1877 in military terms as used in the United States Army’s account distorts the actions of the Nez Perce. Wells supports his argument “The use of military concepts and terms is appropriate when explaining what the whites were doing, but these same military terms should be avoided when referring to Indian actions”; The United States use of military terms such as “retreat” and “surrender” has created a distorted perception of the Nez Perce War, to understand this may lend clarity to the political and military victories of the Nez Perce."[22]

Aftermath

Joseph's fame did him little good. By the time he surrendered, 150 of his followers had been killed or wounded. Their plight, however, did not end. Although Joseph had negotiated a safe return home for his people, General Sherman forced him and 400 followers to be taken on unheated rail cars to Fort Leavenworth, in eastern Kansas, to be held in a prisoner of war campsite for eight months. Toward the end of the following summer, the surviving Nez Perce were taken by rail to a reservation in the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) for seven years. Many of them died of epidemic diseases while there.

In 1879, Chief Joseph went to Washington, D.C. to meet with President Rutherford B. Hayes and plead his people's case. Although Joseph was respected as a spokesman, opposition in Idaho prevented the U.S. government from granting his petition to return to the Pacific Northwest. Finally, in 1885, Chief Joseph and his followers were allowed to return to the Pacific Northwest to settle on the reservation around Kooskia, Idaho. Instead, Joseph and others were taken to the Colville Indian Reservation far from both their homeland in the Wallowa Valley and the rest of their people in Idaho.

Joseph continued to lead his Wallowa band on the Colville Reservation, at times coming into conflict with the leaders of 11 other tribes living on the reservation. Chief Moses of the Sinkiuse-Columbia, in particular, resented having to cede a portion of his people's lands to Joseph's people, who had "made war on the Great Father".

In his last years Joseph spoke eloquently against the injustice of United States policy toward his people and held out the hope that America's promise of freedom and equality might one day be fulfilled for Native Americans as well. In 1897, he visited Washington again to plead his case. He rode in a parade honoring former President Ulysses Grant in New York City, with Buffalo Bill Cody, but he was a topic of conversation for his headdress more than his mission.

In 1903, Chief Joseph visited Seattle, a booming young town, where he stayed in the Lincoln Hotel as guest to Edmond Meany, a history professor at the University of Washington. It was there that he also befriended Edward Curtis, the photographer, who took one of his most memorable and well-known photographs. Joseph also visited President Theodore Roosevelt in Washington, D.C., that year. Everywhere he went, it was to make a plea for what remained of his people to be returned to their home in the Wallowa Valley. But it would never happen.[23]

Death

An indomitable voice of conscience for the West, in September 1904, still in exile from his homeland, he died - according to his doctor - "of a broken heart".[24][25] Meany and Curtis helped Joseph's family bury their chief near the village of Nespelem.[26]

Joseph is buried in Nespelem, Washington, where many of his tribe's members still live.[25]

Legacy

The Chief Joseph band of Nez Perce Indians who still live on the Colville Reservation bear his name in tribute to their prestigious leader. His legacy lives on in numerous other ways. Chief Joseph is depicted on previously issued $200 Series I Savings bonds.[27]

Chief Joseph has been portrayed in multiple media. Notable dramatic works depicting Chief Joseph include:

- I Will Fight No More Forever (1975), an historical drama starring Ned Romero.

- Robert Altman's revisionist Western film Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson (1976). is based on the Broadway play Indians.

- From 1969 to 1970, the late actor George Mitchell played Chief Joseph on Broadway in the play Indians.

Literary works include:

- Merrill Beal's I Will Fight No More Forever: Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce War (2000) was received positively both regionally and nationally.[28]

- Chief Joseph is portrayed sympathetically in Will Henry's novel of the Nez Perce War, From Where the Sun Now Stands (1959). The book won the 1960 Western Writers of America Spur Award for Best Novel of the West.

- Helen Hunt Jackson recorded one early Oregon settler's tale of her encounter with Joseph in her Glimpses of California and the Missions (1902):

Why I got lost once, an' I came right on Chief Joseph's camp before I knowed it . . . 't was night, 'n' I was kind o' creepin' along cautious, an' the first thing I knew there was an Injun had me on each side, an' they jest marched me up to Jo's tent, to know what they should do with me ...Well; 'n' they gave me all I could eat, 'n' a guide to show me my way, next day, 'n' I could n't make Jo nor any of 'em take one cent. I had a kind o' comforter o' red yarn, I wore rund my neck; an' at last I got Jo to take that, jest as a kind o' momento."[29]

- In the children's fiction book, Thunder Rolling in the Mountains, by Newbery medalist Scott O'Dell and Elizabeth Hall, the story of Chief Joseph is told by Joseph's daughter, Sound of Running Feet.

- The saga of Chief Joseph is depicted in Robert Penn Warren's poem "Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce" (1982).

Memorials to Chief Joseph include:

- A statue of Young Chief Joseph in Enterprise, Oregon

- A wall-mounted quote by Joseph in The American Adventure in the World Showcase pavilion of Walt Disney World's Epcot

Multiple man-made and geographic features have been named for Joseph, such as:

- Chief Joseph Pass in Montana[27]

- The city of Joseph, Oregon,[27] home of "Chief Joseph Days" festival.[30]

- Joseph Canyon, in northern Wallowa County, Oregon, and southern Asotin County, Washington[27]

- Joseph Creek, on the Oregon-Washington border[27]

- Chief Joseph Scenic Byway in Wyoming

- Chief Joseph Dam on the Columbia River in Washington, the second largest hydropower producer in the U.S. and is the only dam in the Northwest named after an American Indian.

Oral history

- A handwritten document mentioned in the Oral History of the Grande Ronde recounts an 1872 experience by Oregon pioneer Henry Young and two friends in search of acreage at Prairie Creek, east of Wallowa Lake. Young's party was surrounded by 40-50 Nez Perce led by Chief Joseph. The Chief told Young that white men were not welcome near Prairie Creek, and Young's party was forced to leave without violence.[31]

War shirt

In July 2012, Chief Joseph's 1870s war shirt was sold to a private collection for the sum of $877,500.[32]

References

- ↑ According to his doctor

- ↑ TonyIngram - nptwebmaster@nezperce.org. "Nez Perce language". Nezperce.org. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

- ↑ William R. Swagerty, University of the Pacific, Stockton (June 8, 2005). "Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce Indians". Chief Washakie Foundation. Archived from the original on 2013-10-12. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ↑ "THE WEST – Chief Joseph". PBS. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ Trafzer, Clifford E. (Fall 2005). "Legacy of the Walla Walla Council, 1955". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 106 (3): 398–411. ISSN 0030-4727.

- ↑ Josephy, Alvin M., Jr. (1997). The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. Boston: Mariner. p. 334.

- ↑ "Old Chief Joseph Gravesite". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2014-10-23.

- ↑ "The Treaty Period". Nez Perce National Historical Park. National Park Service. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Historical look at boundaries". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. February 25, 1990. p. 5-centennial.

- ↑ Josephy, Alvin M., Jr. (1997). The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. Boston: Mariner. pp. 428–429.

- ↑ Hoggatt, Stan (1997). "Political Elements of Nez Perce history during mid-1800s & War of 1877". Western Treasures. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Charles F. (2005). Blood struggle: the rise of modern Indian nations. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 40–41. ISBN 0-393-05149-8.

- ↑ Brown, Dee (August 9, 1971). "Befriended whites, but Nez Perces suffered". Deseret News. Salt Lake City, Utah. (Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee). p. 1A.

- ↑ Wilson, James (2000). The Earth Shall Weep: A History of Native America. p. 242.

- ↑ McWhorter, Lucullus V. (1952). Hear Me, My Chiefs!: Nez Perce Legend and History. Caxton Press. p. 542.

- 1 2 3 Forczyk, Robert (2013). Nez Perce 1877: The Last Fight. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 8, 41, 45.

- ↑ Howard, Oliver (1881). Nez Perce Joseph: an account of his ancestors, his lands, his confederates, his enemies, his murders, his war, his pursuit and capture. Boston, MA: Lee and Shepard. p. 17.

- ↑ Leckie, Robert (1998). The Wars of America. Castle Books. p. 537. ISBN 0-7858-0914-7.

- ↑ Walsh, James Morrow (n.d.). Walsh Papers. Winnipeg: MG6, Public Archives of Manitoba.

- ↑ Brown, Mark M. The Flight of the Nez Perce. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 407–08, 428.

- ↑ Haines, Francis (1954). "Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce Warriors". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 45, no. 1: 1.

- ↑ Wells, Merle (1964). "The Nez Perce and Their War". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 55, no. 1: 35–37.

- ↑ Pearson, J. Diane (2008). The Nez Perces in the Indian Territory. Norman: U of OK Press. pp. 297–298.

- ↑ Nerburn, Kent (2005). Chief Joseph & the Flight of the Nez Perc. New York and San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

- 1 2 Walter, Jess (July 4, 1991). "Congress asked to save Chief Joseph's grave". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. p. A1.

- ↑ Egan, Timothy (2012). Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis. New York City: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Individual – What I Savings Bonds Look Like". U.S. Department of the Treasury, Treasurydirect.gov. December 27, 2007. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ↑ Beal, Merrill (2000). I Will Fight No More Forever: Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce War. University of Washington Press. ASIN B00J4Z7S9I.

- ↑ Jackson, Helen Hunt (1923). Glimpses of California and the Missions. Boston: Little, Brown & Company.

- ↑ Hopper, Ila Grant (August 22, 1982). "Chief Joseph Days". The Bulletin. Bend, Oregon. p. B6.

- ↑ "Lola Young, Oral History of the Grande Ronde, Eastern Oregon University p. 32" (PDF). Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ "Chief Joseph's War Shirt Fetches Nearly $900,000 at Auction". Indian Country Today. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

Further reading

- Aoki, Haruo (1994). Nez Perce Dictionary. University of California Publications in Linguistics, Volume 122. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Chief Joseph. Chief Joseph's Own Story. Originally published in the North American Review, April 1879.

- Henry, Will (1976). From Where the Sun Now Stands. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-02581-3.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Chief Joseph |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chief Joseph. |

- Today in History: October 5, U.S. Library of Congress

- Friends of the Bear Paw, Big Hole & Canyon Creek Battlefields

- Chief Seattle and Chief Joseph: From Indians to Icons - University of Washington Library

- PBS biography

- A Personal Web Tribute

- Idaho Genealogy – Idaho Indian Tribes Project – Nez Perce

- Nez Perce.com – Political elements of Nez Perce history during mid-1800s

- "Chief Joseph". Nez Percé Chieftain. Find a Grave. August 28, 1998. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- Works by or about Chief Joseph at Internet Archive